Rahul Choudaha, WES Research & Advisory Services, Kata Orosz, Li Chang, WES Research & Advisory Services

International students aiming to study abroad form a highly heterogeneous group. Differences in academic preparedness and financial resources translate into differences in what information students look for and where they look for it during their college search. By gaining a deeper understanding of how students differ in profile and behavior, higher education institutions (HEIs) can become more effective in their resource allocation and recruitment efforts. With that in mind, we have sought to segment prospective U.S.-bound international students by mapping their profiles according to differences in their information-seeking behavior.

This research report1 [1] presents insights from an online survey of nearly 1,600 prospective international students from 115 countries, administered October 2011 through March 2012. The first section discusses the profiles of U.S.-bound international student segments. The next section outlines how the use of information channels and information needs vary by segment. A separate section is devoted to the profile and information-seeking behavior of students from China and India. And the concluding paragraphs offer recommendations for effective international recruitment.

Understanding the differences in international student profiles can help HEIs prioritize their outreach strategies. Debates about the use of agents and social media should be grounded in an understanding of which segments use the channels and whether the institution is interested in recruiting those segments. To recruit and retain the best applicants for their institution, HEIs need to understand that not all international students are the same.

Profiles of U.S.-Bound International Student Segments

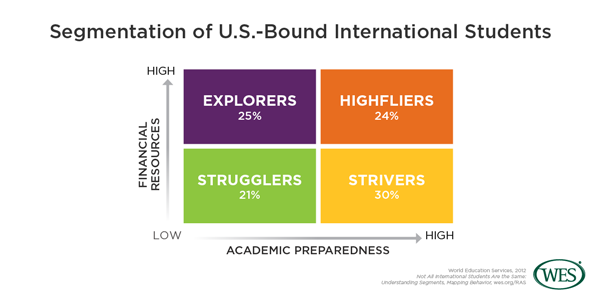

For this study, we segmented the U.S.-bound international student population along two dimensions: academic preparedness and financial resources. We used information on English proficiency and other criteria to categorize our survey respondents as having either high or low levels of academic preparedness. Similarly, we distinguished between individuals with high and low financial resources based on whether respondents expected institutional financial aid to be available to them. Using our survey data, we established the following four segments of U.S.-bound international students:

- “Strivers”: High academic preparedness; low financial resources (30% of all respondents).

- “Strugglers”: Low academic preparedness; low financial resources (21%).

- “Explorers”: Low academic preparedness; high financial resources (25%).

- “Highfliers”: High academic preparedness; high financial resources (24%).

“STRIVERS” are the largest segment of the overall U.S.-bound international student population. Almost two-thirds of this segment (63%) was employed full-time or part-time during the application process, presumably because they need to support themselves. Among all segments, they are the most likely to select information on financial aid opportunities among their top three information needs (45%). Financial challenges do not deter these highly prepared students from pursuing their academic dreams: 67% plan to attend a top-tier U.S. school.

“STRUGGLERS” make up about one-fifth of all U.S.-bound international students. They have limited financial resources and need additional preparation to do well in an American classroom: 40% of them plan to attend an ESL program in the future. They are also relatively less selective about where they obtain their education. Only 33% of them selected information about a school’s reputation among their top three information needs.

“EXPLORERS” are very keen on studying abroad but their interests are not exclusively academic. Compared to the other segments, they are the most interested in the personal and experiential aspects of studying in the United States, with 19% of this segment reporting that information on student services was in their top three information needs during the college search. “Explorers” are not fully prepared to tackle the academic challenges of the best American institutions and are the most likely to plan to attend a second-tier institution (33%). They are also the most likely to use the services of an education agent (24%).

“HIGHFLIERS” are academically well prepared students who have the means to attend more expensive programs without expecting any financial aid from the school. They seek a U.S. higher education primarily for its prestige: almost half of the respondents in this segment (46%) reported that the school’s reputation is among their top three information needs. “Highfliers,” along with “Explorers,” form the emerging segment driven by the expanding wealthy classes in countries like China and India.

Segment-based information highlights the potential trade-offs in international recruitment. “Strivers” are academically highly prepared, but they may not enroll at a school unless they receive financial aid. “Explorers” and “Highfliers” don’t expect institutional financial aid, a boon for financially exigent colleges and universities. However, “Highfliers” are attracted to a narrow circle of top-ranked institutions, which makes it difficult for lower-ranked institutions to compete for them. “Explorers” and “Strugglers” are less selective about their college choice, but they require additional academic assistance both during admissions and once on campus. Institutions must take a realistic stock taking of their ability to meet the diverse needs of their international student bodies, be it a need for financial aid or for academic assistance. A mismatch between institutional capacities and international student needs can harm the financial and reputational well-being of the institution.

The distribution of international student segments varies from region to region. The largest segment was “Strivers” in most regions, with the exception of the Middle East where “Explorers” made up 45% of all respondents. Regional averages, while useful in highlighting regional peculiarities, mask differences among countries within the same region. For example, the top three sending countries of U.S.-bound international students are all located in Asia, but the distribution of segments is markedly different — the largest segment among Chinese respondents was “Highfliers” (32%), among Indians it was “Strivers” (46%) and among Koreans “Explorers” (40%).

Differences in the Use of Information Channels

The two most popular information channels used by international students during their information search are institutional websites and personal networks (family & friends). On average, 90% of the survey respondents used institutional websites to obtain information, and 67% consulted their family and friends for the same purpose. However, social media is an important emerging source of information for international students, with around one-third of respondents indicating that they had used this channel during their information search. The use of agents is not as widespread, with only one out of six respondents reported to have used this channel.

Social media

Social media is a recruitment channel with low barriers of engagement. It is effective at reaching all international student segments, because we found that its popularity does not vary greatly by segment. Among respondents who used social media during their college search, more than half (56%) started following social media accounts managed by U.S. colleges or universities before they decided which institutions they would apply to, and an additional 37% started following institutional accounts before deciding which admissions offer to accept. These findings highlight the potential that skillfully managed social media accounts have for converting prospects.

International recruitment via social media can realize its full potential if institutional social media accounts are updated with current, relevant information and provide ample opportunities for interaction. In addition, HEIs need to find the most appropriate platforms for reaching target student segments. We found that only 22% of Chinese social media users log in to U.S.-based social media platforms (e.g. Facebook, Twitter) on a daily or weekly basis, as opposed to 88% of Indian respondents. At the same time, 80% of Chinese social media users checked their accounts on Chinese social media platforms on a daily or weekly basis, while only 24% of Indian respondents did so. This underscores the importance of building a presence on local social media platforms for HEIs that want to recruit from China.

Agents

Our study suggests that agent use might not be as widespread as previous research has suggested, with only 16% of all respondents reported to having used an agent. Agents were found to assist applicants primarily with two tasks: university shortlisting and application. 77% of our agent-using respondents received assistance during the application process, and 75% were assisted by their agent in university shortlisting. “Strugglers” were found to be particularly likely to use services such as essay, resume or personal statement editing. Seventy-two percent of “Strugglers” had their agents edit their written material (compared to 45% of “Highfliers”) and 63% prepared for admissions interviews with the help of agents (only 34% of “Strivers” did so).

Overall, agents have high barriers of engagement with prospective students as they charge substantial fees. Compared to social media, they are less effective in reaching different student segments. We found that respondents whose academic preparedness was low were overrepresented among agent-users: 40% of our agent-using respondents were “Explorers” and 22% were “Strugglers”. HEIs considering the use of agents for international recruitment purposes should be aware that the typical agent-using student needs plenty of guidance and support not only during the application process, but also during their first semesters in the United States. Therefore, institutions must realistically assess their capacity to provide ample academic support – such as ESL and foundation courses – to international students with low levels of academic preparedness before they engage the services of third-party recruiters.

Differences in Information Needs

International student segments differ, not only in terms of the channels they use during college search but also in terms of the information they need. Availability of financial resources, for instance, can dictate the information needs of prospective students. “Strugglers” and “Strivers” were much more interested in information on financial aid opportunities than their affluent peers. There were also statistical differences in information needs according to academic preparedness; “Strivers” and “Highfliers” were much less interested in student services than their less academically-oriented peers.

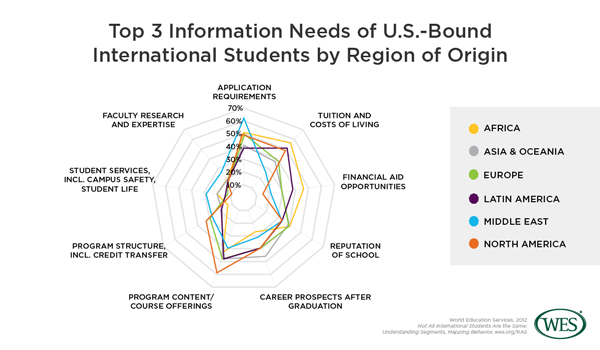

Information needs vary substantially depending on place of origin. Respondents from Africa were much more likely to be interested in information on financial aid opportunities than respondents from other regions: 47% of respondents from Africa selected this information among their top three information needs. Respondents from the Middle East were the most likely to express interest in information about student services, including campus safety: 27% selected this topic among their top three information needs. Among all regions, respondents from Asia & Oceania were the most likely to be interested in information on career prospects after graduation (44%). HEIs that recruit globally can cater to these different information needs of applicants by offering links on their websites to pages with region-specific information.

In the Spotlight: India and China

With more than 700,000 Chinese and Indian students enrolled in higher education institutions abroad, every third globally mobile student is from these two countries. But while both countries send a staggering number of students to higher education institutions abroad, there are marked differences in the socioeconomic backgrounds of the two expatriate student bodies. While 73% of Indian respondents said they expected institutional financial aid to be available to them in the United States, just 40% of Chinese respondents did so.

Differences in socioeconomic status between Chinese and Indian applicants are also manifest in different information needs. Obtaining information about tuition and living costs, as well as about financial aid opportunities was very important for respondents from India: 46% selected tuition and living costs and 38% selected financial aid opportunities among their top three information needs. Information on these aspects of a U.S. education was not as important for respondents from China, with only 22% ranking information on either of these topics among their top three information needs.

Attending a college or university in the U.S. is seen by both Chinese and Indian applicants as an investment for future high-paying jobs. This is reflected by their interest in information on career prospects after graduation – about half of Chinese (55%) and Indian (46%) respondents selected this topic among their top three information needs. If American HEIs wish to maximize the effectiveness of their outreach to applicants from China or India, they should highlight those aspects of their programs that enhance their graduates’ employment prospects, such as internship opportunities or career counseling.

Key Findings and Conclusions

- International students are not the same. International recruitment targets need to be aligned with the institution’s mission and based on a realistic account of its capacity to meet the needs of target student segments.

- Different students use different information channels. Debates about the use of agents and social media should be grounded in an understanding of which student segments use these channels and whether the institution is interested in recruiting those segments.

- Different students need different information. Institutions can meet the information needs of international students more appropriately if they map recruitment channels with the information-seeking behavior of their target student segments.

The financial and reputational stakes of international recruitment are getting higher. Competition for international students coupled with the complexity of navigating different markets and using new outreach channels is compelling higher education institutions to better understand the differences of their international applicants.

This study has addressed this institutional imperative by empirically defining international student segments in terms of their academic preparedness and expectations of financial aid, as well as by highlighting inter-regional and inter-country differences in international students’ information-seeking behavior. A deeper understanding of student segmentation can help higher education institutions prioritize their outreach strategies and map their recruitment channels within target student groups.

1. [4] This WENR article is a summarized version of the full research paper.