By Nick Clark, Editor, World Education News & Reviews

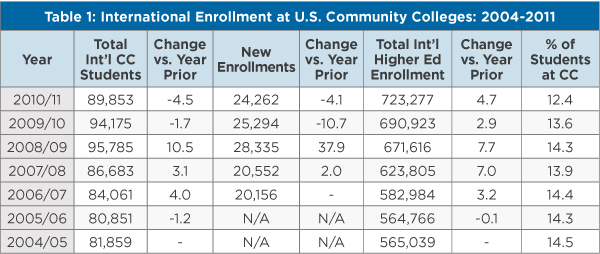

Across the United States, international student enrollment at community colleges hit all-time highs in academic year 2008/09, growing 10.5 percent in one year to 95,785 with new enrollments spiking almost 38 percent to 28,335, according to data [2] from the Institute of International Education [3] (IIE). Since then, enrollment has tailed off slightly, despite continued growth in overall international tertiary enrollments, with the total body of community college students standing at 89,853 in 2010/11, or 12.4 percent of all international students in U.S. higher education.

The timing of the enrollment spike suggests the global financial crisis had a role to play in the increased interest for community college study, given the considerable cost savings of taking core classes at the community college level before transferring to a four-year institution. However, the subsequent drop-off in interest is intriguing, and perhaps representative of the difficulty many two-year institutions have in promoting themselves abroad. Recent cuts to state funding have made a tough situation even harder due to tighter recruiting budgets and increased tuition rates.

Speculating on the recent enrollment trends, Carol Stax Brown, President of Community Colleges for International Development [5] (CCID), warns that the Open Doors data “should be taken with a grain of salt” due to the challenges that many understaffed international offices – where they exist at the community college level – have in completing the IIE’s data request forms. Nonetheless, Brown recognizes that the IIE data is the most reliable currently available.

Sending Country Trends

Students at community colleges come from a diverse range of countries, and while the top source countries align to a degree with the broader overall tertiary enrollment picture, there are clearly countries where the U.S. community college model is better understood and appreciated than in others.

Among Chinese students, for example, community colleges tend to be a far less popular option than the traditional university route. Community college enrollments accounted for less than 6 percent of the total Chinese tertiary body in the United States in 2010/11, while as a percentage of the total international body, Chinese students in the two-year sector represented just one in 10 students – versus more than one in five of all international higher education enrollments.

Even more telling is the distribution of Indian students across academic levels. Of the 103,895 Indian students in U.S. institutions of higher education in 2010/11, just 2.6 percent, or 2,336, were studying at the community college level. And among the 28,145 Canadian students, the fourth biggest cohort of international students in the U.S., just 1,438 were attending community colleges in 2011.

On the flip side of the coin, students from countries and territories such as Vietnam, Mexico, Hong Kong, Nepal, and Indonesia enroll at the community college level at a disproportionally higher level than students from other countries. In the case of Vietnam, almost 60 percent of students in U.S. higher education were attending a community college in 2010/11. This compares to 12.4 percent at the community college level among all international students. Meanwhile, 40 percent of students from Hong Kong were studying at the two-year level in 2011, along with 31 percent of Mexicans and Indonesians, and 28 percent of Nepalese students.

One explanation for the divergent popularity among international students for community colleges is that of branding and perception. Discussing the relative lack of interest from China and India, Mrs Brown from CCID suggests that “elitist perspectives” might be at play.

“Students in those countries, parents in particular, tend to be hung up on the name. In India, community colleges are generally looked down upon. They have no resemblance to the U.S. sector, and no university transfer agreements … we haven’t done a great job educating people there about community colleges,” Brown said, adding that “in countries like Indonesia, the sector is discussed in a much more positive light.”

Nithy Sevanthinathan, Director of International Programs and Services [7] at the Houston-based Lone Star College System (LSCS), agrees with the assessment of Chinese and Indian attitudes towards community college.

“There is a rapidly growing middle class in these countries. Engines of the middle class always want to invest in the best education. The word community college is seen by many there as having a stigma, or it’s just not understood,” said Sevanthinathan who also noted that in addition to students from Lone Star’s traditional markets of Mexico, Venezuela and Colombia – dictated by geography – interest from Vietnam and Nepal has been surging over the last three years.

Sevanthinathan points to a “huge partnership” with the Vietnamese Ministry of Labor for ESL and workforce programs in helping explain the popularity of Lone Star programs there, adding that “wherever Houston oil flows, we would like to see partnerships. We love to build the middle class.”

Also reflecting on the popularity of community colleges among Vietnamese students, Mark Ashwill [8], managing director of Capstone Vietnam [9], an education services company based in Hanoi, said that he remembers, “organizing the first ever U.S. community college fairs back in 2006 … some of my IIE colleagues thought I was crazy, that having the annual fall U.S. higher education fairs consecutively would result in ‘fair fatigue’ and diluted attendance. Both were great successes.”

Capstone Vietnam continues to organize annual community college fairs in Vietnam, and Ashwill says that “Vietnam has become a priority country for many community colleges,” pointing out that “a growing number are actively recruiting here.”

Mr. Ashwill first arrived in Vietnam in 2005 to take up the position of country director with the Institute of International Education. He has seen a dramatic change in perception towards community colleges since then.

“There was very little awareness here about the benefits and advantages of community colleges as a gateway to a four-year school and a bachelor’s degree. That has changed dramatically in the last seven years. U.S. community colleges are now all the rage in Vietnam for all the usual reasons, including quality education at a reasonable cost, an open admissions policy, transfer opportunities and aggressive recruiting on the part of a growing number of community colleges.”

Receiving Institution Trends

Houston Community College (TX) has been the most-popular two-year institution for international students since the 2004/05 academic year, while Santa Monica College (CA) has been the second ranked two-year institution for all but one of those years (2006/07). Montgomery College (MD), De Anza College (CA), Lone Star College System (TX), and CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College (NY) have all had a share of the third, fourth and fifth spots.

Currently, there are 6,250 international students from 147 countries enrolled at Houston Community College (HCC), which ranks sixth among all postsecondary institutions enrolling international students, and first overall in the state of Texas above both the University of Texas-Austin (5,323 in 2010/11), Texas A&M University (4,874), and the University of Houston (4,377).

In the two-year sector alone, there are currently 18 community colleges that have an enrollment of 1,000 or more international students, with HCC enrolling more than double the number of any other. As a point of comparison, the University of Southern California (the top U.S. enroller of foreign students) had a total 8,615 international students in academic year 2010/11, while the top 25 four-year colleges all had an international enrollment in excess of 4,000 students.

Speaking to the Houston Chronicle in September, Alan Goodman, President of the Institute of International Education, predicted that, “we’re going to see more and more international students start at community college.”

Discussing the benefits of a community college education, Goodman suggests that for those arriving with limited English, it is a particularly good option.

“The English language is difficult to acquire. [International students] often need acculturation and teachers who will help them. They are more likely to find that at a community college.”

Mrs. Brown from CCID agrees, noting that, “universities who accept international students from community colleges know that they will be successful and that they already have the English skills necessary for their higher level coursework. So, while some people may think universities and community colleges are competing for international students, universities will have a better completion rate from transfer students. Plus, they do not have to invest in the special services or English language support that community colleges already have in place.”

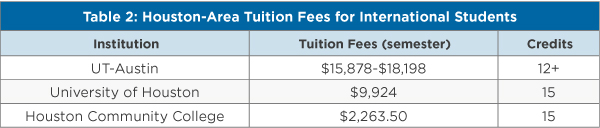

For international students, these benefits come in addition to considerable cost savings. By way of example, for students looking at an education in Texas, two years of study at Houston Community College could save as much as $60,000 versus the option of taking the first two years at the University of Texas (see table 2).

Community Colleges As An International Model

While community colleges may not have the resources, incentives or mission that four-year schools have when it comes to internationalizing their campuses, there is growing interest from abroad in replicating the U.S. two-year model among industrializing nations that have limited capacity in their universities, but need a skilled cadre of workers to fill positions in new and emerging technical sectors of the economy.

By way of example, a delegation from the Indonesian Ministry of Education visited Boston’s Bunker Hill Community College [11] (BHCC) in September of this year on a visit sponsored by the Institute of International Education. According to a BHCC news release, the “Indonesian officials were particularly interested in the community college system in the United States as they believe it is a possible model that could be imported to their country.”

Indonesian faculty from colleges and polytechnics have also been engaging in exchanges to the United States to develop an understanding of U.S. community colleges under the Community College Faculty and Administrator Program with Indonesia [12], which is funded by the State Department.

Lone Star Community College is another U.S. institution helping to develop Indonesia’s community college sector. It is working with the Indonesian Ministry of Education and institutional partners in Jakarta, the capital, to help shape the two-year model there. According to Mr. Sevanthinathan, the school is working with U.S. multinationals in Indonesia as it builds the programs, which he hopes will be operational in 2013, so that local economies in both Houston and Indonesia can benefit from the partnership.

LSCS is also developing a program in the Central Asian nation of Kazakhstan, which like many of its international tie-ups will be centered firmly on the same engine that fires the Houston economy: oil and gas. Similarly in Brazil, Lone Star has been working with U.S. multinationals there to help develop skilled technicians, where there is currently a dearth in the booming carbon economy.

“Yes, recruitment is about branding Lone Star and an affordable education, but it is also about talking to local governments and building local economies across global borders,” said Sevanthinathan, adding that “community colleges can tie themselves to the global business model by talking to those local businesses that have a global outlook.” And there are plenty of those in Houston.

There is also interest in the sector from India. Earlier this year, a delegation attended the American Association of Community Colleges [13]’ (AACC) annual convention [14] to learn more about the U.S. community college model and how it might be adapted in India. The delegation included five state ministers of education and high-ranking education officials from the national government.

The ministers who came to the AACC convention are part of a committee charged with developing a community college model for India with a goal of improving tertiary completion rates and improving graduates’ employability. Under a pilot scheme, India has set a goal of establishing 100 new community colleges by 2017.

The Wadhwani Foundation [15] in India is working with national and state governments, private industry and other organizations to increase access to higher education in the country. The foundation coordinated the AACC visit, and already has partnership agreements with Maryland’s Montgomery College [16], which received a two-year $195,000 grant [17] from the U.S. State Department [18] in 2010 to conduct a national symposium on community colleges in New Delhi (2011) and “build international cooperation, diplomacy and education in India.” The college also has a memorandum of understanding [19] to help train faculty through a community college faculty development center in India that will be developed with the Wadhwani Foundation and Jindal Education Initiatives [20], a philanthropic initiative of Jindal Steel and Power Limited.

Although there are an estimated 500 operational community colleges in India, the only university that accepts transfer credit is the Indira Gandhi National Open University [21]. Currently there is no broadly accepted middle route between high schools and universities similar to the U.S. community college model.

In Qatar, Houston Community College has been instrumental in developing curriculum, training faculty and developing operating procedures and policies for the newly instituted Community College of Qatar [22], which opened this year with more than 300 students who will be able to transfer credits to four-year institutions in Qatar.

Internationalization Challenges

Over the last decade, community colleges have certainly made gains in internationalizing their campuses, but according to the findings of a recent survey [23] of 239 community colleges (from a total of 1,869 associates colleges nationwide) by the American Council on Education [24] those gains have come at a much slower pace than is the case at four-year schools.

Overall 50 percent of community colleges survey respondents “perceive that internationalization has accelerated on their campuses in recent years.” However, among those, just 26 percent have “implemented campus-wide policies or guidelines for developing and approving partnerships or assessing existing partnerships.” This compares to three-quarters of doctoral institutions.

In 2011, 48 percent of doctoral institutions, 39 percent of master’s institutions, and 41 percent of baccalaureate institutions had a strategic international student recruitment plan that included specific enrollment targets, while 13 percent of associate institutions and 21 percent of special focus institutions reported having such plans.

With regards to recruiting, just 15 percent of two-year institutions fund travel to recruit abroad, down from 16 percent in 2008 and up from 12 percent in 2001 (the last two times the surveys were conducted). However, academic support services for international students have dropped from 68 percent to 50 percent in the past five years.

Somewhat surprisingly, the percentage of institutions with English as a Second Language (ESL) programs increased in every sector except among associate institutions, which saw a decrease from 79 percent to 61 percent between 2008 and 2011. Nonetheless, “the percentage of associate institutions with ESL programs is still greater than that of the baccalaureate and master’s sectors.”

The report concludes that, “while associate institutions have made progress in some areas, their overall levels of internationalization are still below those of institutions in other sectors. Given that approximately 40 percent of U.S. undergraduates attend associate institutions, developing and sharing successful internationalization models and strategies for these institutions should be a priority for the U.S. higher education community going forward. In addressing this challenge, it will be important to move beyond models that have worked for more traditional student populations. Finding ways to bring global learning to non-traditional students should be seen as an essential aspect of providing quality education to all students, and as an important element in America’s higher education attainment agenda.”

This is no easy task. Mrs. Brown from CCID, a coalition of two-year institutions that is primarily focused on building the capacity of community colleges to host international students, points out that many two-year institutions are located in rural areas with poor public transportation and limited housing options.

“State law prohibits many community colleges from building dormitories. They need to develop partnerships with private housing providers. Transportation in many rural communities is a challenge too,” Brown said, adding that CCID is focused on “making sure community colleges are ready to be good host institutions and that they are able to provide a positive experience for international students once they are there.”

Mr. Sevanthinathan from LSCS notes that the State Department’s EducationUSA [25] advising centers around the world have been very helpful in promoting community colleges. However, at the diplomatic and consular level, the support and understanding of the sector has – at times – been lacking. This has caused problems for some students in procuring visas to study at the community college level, and it is an issue that Sevanthinathan, along with other schools and community college organizations, have been working to improve in dialog with the government and individual consular offices.

Vijaya Khandavilli is a former EducationUSA adviser, now operating independently as an education advisor to internationally mobile Indian students, and according to the findings of a survey of Indian students she recently conducted, community colleges still have a long way to go in terms of being understood in India. Mrs. Khandavilli suggests that because word of mouth is such a powerful recruiting tool, community colleges need to engage their local Indian communities.

“One of the ways for community colleges to gain familiarity in India would be to offer open house visits or sessions to Persons of Indian Origin in their locality. A good number of Indian students are interested in engineering and business fields of study. Students would likely consider colleges which have strong programs in these fields and that can offer internships or curricular practical training.”

Successful Recruiting Models

A key to the success of many of the two-year institutions that have large international student bodies is the ability to promote themselves as pathways to an end result beyond the community college.

“Successful community colleges have been working with universities to build transfer routes, as parents internationally tend to be more concerned with the outcome than the process. So colleges that have been successful are those that have been promoting themselves as a pathway to a university degree. They all have good partnerships, but this needs to be carried over to the recruiting process,” said Mrs. Brown.

Offering an example, Mrs. Brown points to a recent recruiting trip to Indonesia and Vietnam by administrators from Kirkwood Community College [26], the Iowa-based institution that hosts the CCID offices. Travelling with representatives from the University of Iowa, Kirkwood staff handed out brochures clearly highlighting specific pathways to a university degree at partner institutions.

Mr. Sevanthinathan at Lone Star offers a similar explanation with regards to his institution’s international recruiting success. Not only is the tuition affordable ($5,500 per year for a full-time 30 credit load), but class sizes are small and the academic pathway personalized.

“We offer personalized ‘completion by design’ routes to a university degree. Each semester we tell students, this will be your pathway to that degree in terms of university admissions criteria.”

Lone Star also hosts a University Center [27] on two of its campuses, where students can take junior- and senior-level classes from one of several university partners, and graduate with a bachelor’s or master’s degree without leaving the LSCS campus. Sevanthinathan says that the international office “thrives on that model,” and is also very clear with students about other transfer options.

In Washington State, Green River Community College [28] has been able to leverage favorable state laws to run a successful international recruiting program. Not only do they promote themselves as a stepping-stone to a university degree, but also to a high school degree.

“An attractive option for parents and students that is unique to Washington State is the high school completion program. Thanks to state legislation in 1990, students can earn a Washington high school diploma and a university transfer associate degree in just two years, assuming their English proficiency is up to par. In addition to saving time and money, killing two birds with one stone, so to speak, high school completion programs enable students to make a smooth linguistic and cultural adjustment and better prepare them for university study,” said Mark Ashwill, who added that in the Vietnamese context, it offers “parents of means who cannot afford an overseas boarding school a cost-effective option for their children to obtain a quality education, something that is in short supply at home.”

Also of importance, says Mrs. Brown, is the fact that Green River has invested heavily in ensuring that international students there are having a positive, well-supported experience. She points out that the school has built dormitories for international students and that they have put significant resources into the support services of the International Office [29].

“Community colleges make a great place for students from abroad because of the individualized attention,” says Brown, who points out that many international students end up engaging in “reverse transfers,” where they enroll in a university, struggle with language requirements, transfer to a community college, take core classes and improve English skills and then transfer back to their four-year program.

Of course, the community college is a means to an end itself and not just a conduit to a four-year degree. In recognizing this, the State Department funded a program in 2007, designed to bring non-elite international students to U.S. community colleges from countries such as Brazil, Egypt, India, Pakistan, and Turkey to earn a one-year professional certificate. The Community College Initiative (CCI) Program [30] has brought close to 1,500 students from 1,600 countries to a diverse range of 40 different colleges in the U.S.

CCID administers the program and Mrs. Brown has been happy with its success, noting that many students have gone on to start volunteer and grassroots organizations in their home countries. While in the United States, students have to perform 60 hours of community volunteering and for many international students this has been a new experience. Another positive of the program is that the vast majority of the State Department funding is spent in the United States.

“It has been an amazing program, as the group of students have all been the first in their families to go onto higher education, unlike the more elite level of international student at the university level. Community college is a great place for these students because of the support services,” said Mrs. Brown, also noting that the program offers “training wheels for a lot of new colleges looking to get started enrolling international students.”