Education in Venezuela is administered and regulated by the Venezuelan Ministry of Education and is highly centralized. Education is compulsory for the first nine years (educación básica) and is taught in Spanish. After nine years of basic education, students are streamed into either the humanities or the sciences at the diversified secondary education level (educación media diversificada), which lasts two years and leads to the award of the bachiller. Alternatively, secondary students can follow a two- to three-year specialized curriculum (educación media profesional) leading to the award of a technical degree. Education is free to all and at all levels of the system; however, private schooling is popular, especially at the secondary level. Both public and private schools are subject to supervision by the ministry, and must meet the same standards.

Given the centralized nature of the education system, the 14-year rule of President Hugo Chávez, who died this March, was transformative at all levels, but especially so at the tertiary level. Under Chávez’s Bolivarian Missions social outreach program, launched in 2003, a focus on literacy programs and university preparatory programs greatly expanded educational opportunities to previously excluded groups from poor areas of the country. In conjunction with the introduction of open university admissions and the creation of new public universities, the university outreach programs have helped grow enrollments from 670,000 in 1998 to almost 2.5 million today.

A new university, the Bolivarian University of Venezuela [1] was created in 2003 for the masses, with enrollment open to all regardless of prior educational experience, qualifications or nationality. The university currently enrolls in excess of 180,000 students, with an eventual goal of enrolling one million students at campuses across the country. Graduates of the institution, currently numbering approximately 200,000, are expected to staff other social programs under the broader Social Missions network, staffing free public health clinics, literacy centers and government media outlets. Critics of the new institution see it as an arm of the government’s propaganda apparatus, ruled by Marxist doctrine, and a further challenge to traditional values of university autonomy within the country.

Traditionally autonomous universities – long the preserve of Venezuela’s upper and middle classes – have fought hard to stave off challenges from the government to their academic freedom and institutional autonomy. The current law governing higher education dates back to the 1970s, and while all parties involved in the higher-education debate agree that the law needs updating if higher education is to respond to the 21st century needs of the nation, attempted Chávez reforms have been lightening rods for protests among university administrators and student groups. These constituencies also point to severe underinvestment in autonomous universities and academic research, a reality that continues to force a significant migration of academic talent overseas.

The question of university reform remained unresolved at the time of Chávez’s death, and Venezuela’s tertiary system looks set to continue in a relative state of crisis given the recent election of Chávez’s appointed successor Nicolás Maduro and the continuation of the regime.

Speaking recently [2] in Dubai at Going Global, the British Council’s conference for higher education leaders, Orlando Albornoz, professor of education at the Central University of Venezuela [3], told delegates that those in charge of higher education in his country would remain deeply committed to a “different vision” of university education than that held by those from the traditional university sector.

International Students

An estimated 9,000 Venezuelan scientists are currently living in the United States – compared with 6,000 employed in Venezuela – and as many as one million total Venezuelans migrated overseas during the Chávez era. A study released in 2009 by the Latin America Economic System [4], an intergovernmental economic research institute, found that the outflow of highly skilled labor, aged 25 or older, from Venezuela to OECD countries rose 216 percent between 1990 and 2007, while a 2008 study by Vanderbilt University [5] showed that 47 percent of 18-year-olds said they planned to emigrate in the next three years.

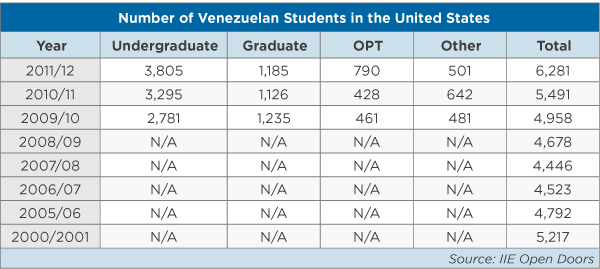

The number of Venezuelans in the United States on student visas grew to 6,281 in 2012, up from 4,678 in 2009, but still well below the highs of the late 1970s to mid 1980s when in excess of 10,000 Venezuelans were studying at U.S. institutions of higher education. At that time, Venezuela was easily the biggest source of students from the Latin American region for U.S. institutions of higher education. The surge in overseas study among Venezuelans up until the economic downturn of the 1980s was largely a result of government efforts to meet the needs of its growing and increasingly sophisticated economy. During that time, the government sent many Venezuelans abroad for training, particularly to the United States and Europe.

Today, Venezuela ranks fourth as a regional source of students at U.S. institutions of higher education, behind Mexico (13,893), Brazil (9,029), and Colombia (6,295). Nonetheless, the last two years has seen a 34 percent increase in enrollments from Venezuela.

Over 60 percent of students in the United States on study visas are currently attending undergraduate programs. Business and engineering are the two most popular fields (25.6 and 15.5 percent of the total respectively), with just over 10 percent undertaking intensive English-language programs.

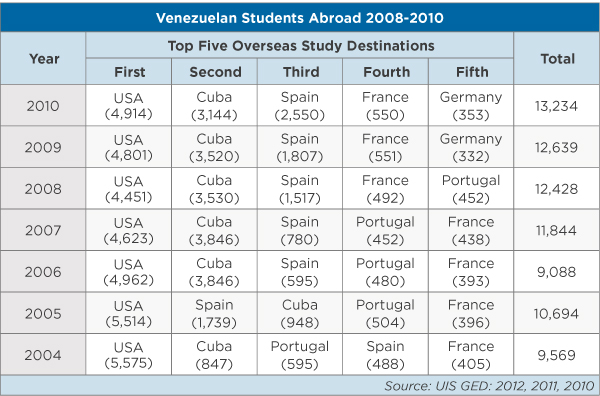

The United States has long been the primary overseas destination for Venezuelan students; however, Chavez’s strategic alliance with Cuba and the focus on links with universities there rather than the United States and Europe has resulted in many thousands of Venezuelans travelling to Cuba to study in recent years, especially in the healthcare fields.

Currency control measures introduced last spring by the Venezuelan Ministry of Higher Education are currently restricting the ability of some prospective international students to fund their overseas educations. According to the new currency exchange measures, only students seeking specific degrees in 172 fields, as designated by the state, are allowed to exchange currency for study abroad through the Foreign Exchange Administration Commission (CADIVI), the national authority in charge of currency transfers. Students of psychology, law, sociology, biology, international studies and the humanities, among others, are not allowed to access foreign currency through CADIVI.

With the new changes, only students studying basic sciences, engineering/ architecture and technology, agriculture and marine sciences, health sciences, education, sport sciences, social sciences or literature/the arts are being granted foreign currency. The government recognizes these as fields of study in which Venezuela does not have enough trained professionals. If the policy stays in place under the new leadership of President Maduro, many students say they will have to continue turning to the black market for foreign currency, adding significant cost and likely reducing the overall mobility of Venezuelan students.

The Education System of Venezuela

Basic Education

Primary education (educación básica) is compulsory from the age of six and free in public schools. Since 1981, the length of primary education has been nine years. Students can attend free pre-school classes if their parents so choose, but this is not compulsory.

Schools are administered and funded at either the national, state or municipal level. Curricular content is much the same at all schools due to strong central control. The school year extends from September through to June or July, and students are assessed on the basis of continuous assessment. Successful students are awarded the Certificado de Educación Básica (Basic Education Certificate).

In 2007, President Chavez introduced a new ‘Bolivarian’ curriculum for all schools in the country, including private ones. A law passed in 2009 granted greater control over curriculum development to the country’s Communal Councils, closely linked to the ruling party, prompting protests about the politicization of the school system. Proponents of the reforms have praised measures designed to significantly increase participation in poor areas of the country. To what degree the curriculum reforms have been implemented is somewhat unclear at this stage.

Secondary Education

Secondary education (educación media) follows the nine-year basic cycle and students follow either the academic stream (two years in length) or a technical/vocational stream, which is most commonly three years in length. Students receive technical and vocational instruction through the school system, or at vocational colleges operated by the Instituto Nacional de Cooperación Educativa [8]. It is also offered at postsecondary level at university colleges, institutes of technology and university institutes. There are both public secondary schools (liceos) and private secondary schools (colegios). Approximately one in four students attend private schools at the secondary level.

The academic stream is subdivided into two options, with students choosing either a science or humanities option. In the technical/vocational stream, students choose from one of five options: agriculture, art, commerce, industrial studies, or social work. All programs are three years in length except commerce, which is two, and typically focused on technical career training.

The academic stream has traditionally been considered of higher prestige than the technical route, and approximately two-thirds of secondary students choose that path, most commonly in the science stream. In addition to specialization-specific subjects, all students must take: Spanish language and literature, mathematics, philosophy, Venezuelan history and geography, physical education and English.

Graduates of the academic stream are awarded either the Bachiller en Humanidades (Bachiller in the Humanities) or the Bachiller en Ciencias (Bachiller in Science). Graduates of the technical/vocational stream are awarded the Bachiller in their chosen field (Bachiller Industrial, Bachiller Comercial, Bachiller en Agropecuario, Bachiller Asistencial (social work) or Bachiller en Arte).

Graduates of both streams can apply for university entrance, although in the past the academic stream has been the traditional route to a university education. These norms have been broken down considerably in recent years under reforms instituted by former president Hugo Chavez that, among other things, ended the national college aptitude test and entrance examinations at public universities in a bid to lower barriers to entry for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. According to government figures, these access policies have had significant success, with the tertiary gross enrollment ratio (total tertiary enrollments as a percentage of the college-age population) rising from 28 percent in 2000 to 78 percent in 2009, well above the regional average of 39 percent.

Higher Education

Higher education in Venezuela is offered at universities, polytechnic institutes, university colleges, institutes of technology and private university institutes. The latter three types of institutions offer short-cycle sub-degree awards known as Técnico Superior.

The country’s six autonomous state universities are the oldest and most prestigious in Venezuela and operate as traditional multi-faculty institutions. They are all publicly funded and autonomously regulated. However, their right to administer their own selection processes was ended in 2009 in an amendment to the Organic Education Law. University stakeholders have been fighting hard in recent years to avoid further erosion of their autonomy by fiercely protesting various iterations of a proposed update of the 1970 law governing universities in the country. However, the creation and expansion of new public universities, in combination with new public funding policies, has left the autonomous universities severely underfunded and in a current state of flux.

Also largely autonomous from state control are 10 national experimental universities. These have a smaller number of faculties focused largely on technical and vocational subjects.

Newer public universities, such as the 200,000-strong Universidad Bolivariana – created by decree in 2003 – offer open admissions and are firmly under the control of the central government. These institutions have been the driving force behind the massive growth in tertiary enrollments over the last decade. At the University of the Armed Forces, for example, enrollment has reportedly grown from 3,200 in 2003 to 224,000 in 2007. Meanwhile, the private sector, which previously accounted for 40 percent of all tertiary enrollments, now teaches less than 20 percent of Venezuela’s student population.

Polytechnic institutes offer five-year programs in engineering and other technical fields and their awards are considered equivalent to university awards. The Ministry of Education directly administers these institutions.

Undergraduate Education

There are two main degree awards at the undergraduate level in Venezuela: the short-cycle técnico superior and the licenciado, the traditional first-degree university award. The former is awarded mainly by institutes of technology, university colleges, and university institutes, although some universities also run programs leading to the award.

The licenciado is typically awarded after five years of study, although a few programs of study are four years in length. The coursework for the licenciado is very specialized with little flexibility in course offerings.

Professional titles in fields such as dentistry, engineering, law and medicine are comparable to the licenciado and are typically five years in length. The professional title in medicine (Médico-Cirujano) is a six-year program.

Graduate Education

At the graduate level there are three main awards: diploma de especialista (specialist diploma) the magister, and the doctorado.

The specialist diploma requires one year of study after the licenciado and provides training in specialized professional fields.

The master’s degree requires two years further study after the licenciado and is offered in both academic and professional fields. Most magister programs require completion of a thesis.

The doctorate degree requires three years of study and is awarded by thesis only. Admission is open to holders of the magister.

Required Documents

For secondary credentials, WES requires that the applicant submit a clear, legible photocopy of his/her graduation certificate or diploma as issued by the Ministerio de Educación (e.g. bachiller, técnico medio). In addition the certificado de notas/calificaciones (academic transcripts) must be sent directly by the institution attended.

For higher education awards, WES requires that the applicant submit clear, legible photocopies of all diplomas and degree certificates issued by the institutions attended (e.g. técnico, licenciado, título profesional, maestría, doctorado). In addition the certificado de notas/calificaciones (academic transcripts) for all post-secondary programs of study must be sent directly by the institutions attended. For completed doctoral programs, a letter confirming the awarding of the degree must be sent directly by the institutions attended.

For vocational and professional awards, WES requires that all graduation certificates (e.g. técnico superior or título profesional) indicating all exams taken and grades obtained be sent directly to WES by the institutions attended. In addition the certificación de notas/calificaciones (academic transcripts) issued by the institutions attended for all programs of post-secondary study should be sent directly by the institutions attended.

Photocopies of precise, word-for-word, English translations are required for all foreign language documents.

Conclusion

The twenty-first century has so far been one of great change for the education system of Venezuela, due in large part to the policies and reform efforts of populist president Hugo Chávez.

Educational outreach programs have brought Venezuelan literacy rates up to regional standards, with the number of children attending school increasing from 6 million in 1998 to 13 million in 2011, and the net enrollment rate (NER: number of primary age children in school as a percentage of the total primary-age population) to 93 percent from 85 percent in 1999. Even more impressively, the secondary NER has risen from 48 percent to 72 percent over the same timeframe. Both figures are now in line with regional averages. At the tertiary level, the gross enrollment ratio has exploded to 78 percent (2009) from just 28 percent in 2000, with open access policies prompting tens of thousands of non-traditional and disadvantaged learners to enter the system.

However, issues related to politicization, underfunding, brain drain, and encroachments on academic and institutional autonomy have left the university system in a precarious position.

The Chávez administration increased student enrollment significantly, creating 13 new universities, but without the necessary budget allocations to support the expansion, quality at all levels has suffered. After clashes between the regime and university administrators in recent years, the future of the traditional university research sector remains highly uncertain, and it remains to be seen if the new leadership of President Maduro can, or is interested in, finding the common ground necessary to move the country’s needed university reform and modernization process forward.