Libya faces significant challenges as it transitions to democracy and begins the process of building a new, post-Muammar Gaddafi nation. One of the most important building blocks will be higher education, and while there currently exist more opportunities for the advancement of the tertiary system than have been seen in over a generation, there also exist significant hurdles.

With six million people, Libya does not have a large population. The nation’s first university was established in the 1950s, and currently there are 13 state universities and seven private universities, educating 300,000 students. In the technical sector, there are a further 91 institutes with a combined enrollment of 71,000 students.

Oil reserves already allow for tuition-free higher education; however, existing institutions of higher learning are bursting at the seams and they are in need of modernization. Many of Libya’s older faculty members were educated in the United States and Britain during the late 1970s and 1980s – the heyday of Libyan academic mobility and an era when the government was attempting to train more qualified Libyan academics for lecturing positions at domestic universities. Today, however, there is a shortage of qualified faculty members.

Today, after decades of international isolation, underinvestment and cronyism under Gaddafi, the system needs help. Fortunately for Libya, the country sits on the largest proven oil deposits on the African continent (and among the top 10 globally, contributing US$132 billion annually to GDP), which means that with the right political leadership, the disarming of militias and the improvement of security, the question of funding is one of the less pressing concerns facing policymakers.

Already, with the removal of the Gaddafi regime, the task of rebuilding and improving higher education is underway. Both the initial interim transitional leadership and the newly elected parliament, the General National Congress (GNC), have indicated their desire to move the country’s education system forward. And by building a human resource base that can staff the nation’s institutions of higher learning and help develop private enterprises, the nation’s new leaders hope to begin chipping away at the country’s massive unemployment problem. The current unemployment rate in Libya is 30 percent, a figure that is of grave cause for concern with regards to the fledgling democracy’s future stability and security. Unemployment has long been a problem in Libya and was one of the main contributing factors to the unrest that led to the overthrow of Gaddafi.

Looking Abroad for Help

Given the essential withdrawal of Libyan higher education from the international arena during the post-Lockerbie years of Gaddafi rule, especially those years when the country was under strict international sanctions, modernizing the system away from a tradition of political loyalty, ideology and patronage, will require input, collaboration and exchange with international partners.

Earlier this year, an agreement was signed [1] between TVET UK [2] and the Libyan Board for Technical and Vocational Education (NBTVE) with the aim of facilitating partnerships and exchanges between Libya and UK vocational education and training agencies in order ‘to help build the necessary and appropriate industrial trades and technical skills capability and capacity for current and future social, economic and industry demands in Libya,’ according to an April news release from the British export-focused association of training providers.

The GNC has prioritized the provision of vocationally oriented training for Libya’s young population (70 percent are under the age of 30), as the country seeks to diversify its economy by training manpower in specific fields relevant to targeted sectors. The NBTVE, therefore, is looking to establish an entirely new VET system to be implemented across the country’s more than 100 higher education colleges and technical institutes.

According to Alan McArthur, Executive Director of TVET UK, ‘building capability is an absolute priority for the Ministry. At the moment, teaching staff have an academic background and approach, and limited industrial experience and this is reflected in the curriculum. Many colleges are empty shells, damaged during the uprising, while others are packed with state-of-the-art equipment with the covers still on and no one able to use it.

‘With regards to the current workforce, there is a high rate of unemployment, bolstered by high numbers of ex-militia seeking work, and an over reliance on the public sector. Around 80 percent of those currently in employment are working in the public sector and the government hopes to reduce this by relocating workers into the private sector. However, these individuals will need to develop a range of new skills if the transition is to be a success.’

According to the terms of the agreement signed between the two sides, TVET UK will be working with a range of UK providers and suppliers to set up workshops in a number of areas, including skills auditing and quality assurance as Libya moves forward with its plans to diversify its economy.

Language Training

Prior to Libya’s period of international isolation, the teaching of English and French was banned under a Gaddafi-imposed plan to ‘eliminate foreign influence.’ Today, this means there is a weak infrastructure for teaching languages in Libya and subsequently strong demand for overseas and domestic foreign-language learning.

Therefore, in addition to redeveloping the technical and vocational training landscape, the GNC has also announced plans to develop language learning through overseas scholarships. In May, a funding initiative of US$2.6 billion dollars was floated by the government that would fund the overseas training of over 10,000 students in technical fields and an additional 31,000 students in English language – as a precursor to higher studies at an overseas institution of higher learning.

In a press conference after the announcement, Deputy Minister of Higher Education, Bashir Echtewi, stated that 5,692 students and 2,004 faculty who already hold masters degrees will be sent abroad, while a remaining 3,616 “top students” will go to foreign universities to complete their studies.

In addition to government scholarships, industry is also looking to put human resource development on the fast track. The National Oil Corporation recently told a delegation [3] of UK English language providers that it had a training budget of US$50-60 million that represented a “golden opportunity” for providers.

The funding proposed by the government represents a more than threefold increase in the current budgetary allocations supporting 12,500 scholarship recipients that are currently studying abroad, many there since before the civil war. However, the state of higher education in Libya has received such harsh criticism since the revolution thanks to overcrowding and poor faculty standards that the decision to send students abroad hasn’t been well accepted by everyone. Many see it as a lost opportunity to invest in building local colleges and institutions.

Libyans Abroad

According to data from the Unesco Institute for Statistics, there were a total of 7,009 Libyans studying overseas at the tertiary level in 2010, with the UK being the most popular destination (2,827 students), followed by Malaysia (1,453), the United States (1,055), France (277), and Canada (243). However, figures quoted by Libyan media put the current number of students abroad on government funding at around 12,500, while the British Council says it expects 17,000 Libyan students in the UK this year alone. During the civil war, the British Foreign Office said that it had an estimated 8,000 Libyan students and their dependents living in Britain, while in Australia more than 1,150 were enrolled in universities and English language programs or other colleges.

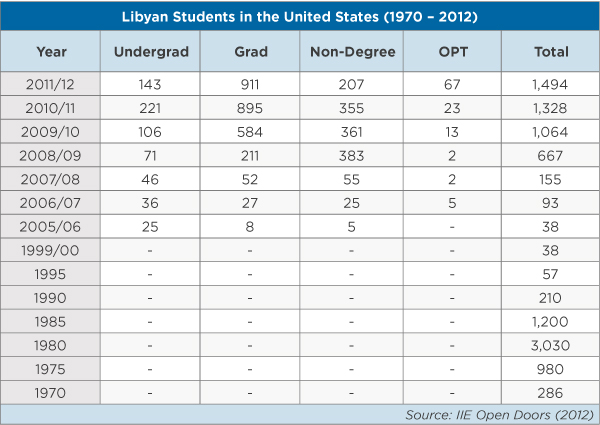

At U.S. institutions of higher education, the number of Libyan enrollments has been surging after a 20-year period during the 1990s and first decade of the current century when less than 50 Libyans on average were annually attending U.S. colleges; from over 3,000 in the 1980s.

Today Libyans are again looking to the United States as a study destination; the U.S. embassy in Tripoli reported nearly 1,700 student applications from across Libya for the 2011-2012 Fulbright student program after a doubling of available scholarships. According to data from the Institute of International Education, total enrollments in U.S. institutions of higher education in 2011/12 reached almost 1,500, an increase of over 1,500 percent in five years.

The massive increase in interest in U.S. higher education began with the normalizing of relations in 2004, but is thanks in large part to the introduction of an overseas scholarship program funded by the Libyan government that has survived – just – the transition of power from Gaddafi.

The Libyan Committee for Higher Education introduced its overseas scholarship program in 2007, sending more than 7, 000 graduate students overseas. During the civil war and in the immediate aftermath of the overthrow of the Gaddafi regime the continuation of funding looked doubtful, but the transitional government resumed payments in early 2012 and now scholarship programs are being expanded.

The Libyan-North American Scholarship Program [5] – a joint collaboration between the Libyan Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, the Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE), Libyan students and host universities in Canada and the United States – has facilitated the studies of Libyan graduate students in North America since the beginning of 2010. Prior to 2010, the program was administered from the Libyan Embassy in Ottawa. According to the scholarship webpage on the CBIE site, there are now approximately 2,000 Libyan students on government scholarships at universities and English language schools in the United States and 500 in Canada. The program covers their tuition fees, medical coverage and living allowances.

Conclusion

The Libyan higher education system faces huge challenges after decades of neglect, yet the country has significant resources to draw upon in upgrading its institutions, research and teaching resources. Given the right political leadership and support from regional and international partners, Libya has the potential to transform its system of higher education into a force for change that is capable of producing jobs, eliminating radicalism and reducing reliance on foreign expertise in its technical sectors, the petroleum industry in particular. And recent initiatives from the newly elected government suggest the impetus is there.

In addition to the huge new scholarship programs that have been announced to train faculty and develop language learning and technical training in the country, Libya is also developing information technology infrastructures to better connect universities, build distance-learning capabilities, and provide access to academic research databases.

Opportunities exist for foreign institutions interested in helping build a post-Gaddafi Libya and many have already developed ties or welcomed Libyan students to their campuses. Partnerships in and with Libya offer benefits to collaborators, but more importantly they can help build the institutions necessary to develop a functioning stable democracy capable of shaping a violence-free Libyan future – one that might one day stand as an example of post-dictatorial renaissance in the region.