Rahul Choudaha, WES Research & Advisory Services, Li Chang, WES Research & Advisory Services, Paul Schulmann, WES Research & Advisory Services

According to a survey [1] by Inside Higher Ed and Gallup, only one quarter of financial officers at American higher education institutions (HEIs) have strong confidence in the viability of their institution’s financial model over the next five years. Moreover, many “acknowledge that their institutions do not have the data or the information to make informed decisions in key areas.”1 [2]

This report endeavors to address the deficit of data on how international student segments differ in terms of their information needs while applying to study at HEIs abroad. In understanding these behavioral patterns, HEIs are more capable of formulating targeted recruitment strategies.

In a previous WES report [3], we segmented international students by their academic preparedness and financial resources, and reported on how these attributes affected their information-seeking behavior as well as what information they needed when applying to U.S. HEIs. This report examines how these patterns differ not only between populations of international students, but within them as well. We achieved this by applying the same principles of segmentation to level of education (bachelor’s and master’s degree) and by country of origin, looking specifically at China, India, and Saudi Arabia. By using a segmentation approach, we were able to differentiate international students at a more granular level.

From October 2012 to March 2013, World Education Services (WES) conducted an online survey in English to applicants for WES’ credential evaluation services. We surveyed those who applied or plan to apply for bachelor’s, master’s or doctoral programs in the U.S. In total, 2,992 questionnaires were completed; nearly double the number of respondents as compared to last year’s report.

Overall Profiles of International Students

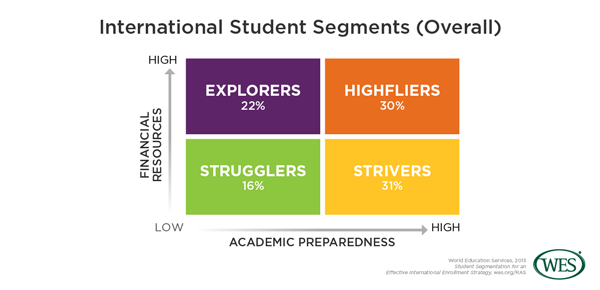

Based on the segmentation of two dimensions: financial resources and academic preparedness; we identified four segments of international students:

Explorers: Students with high financial resources and low academic preparedness

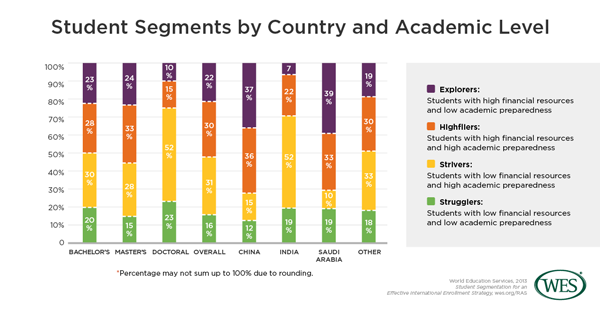

Explorers (22%) constitute the second largest segment overall, and among Chinese (37%) and Saudi (39%) students they form the largest segments. Among Indians, by contrast, Explorers are the smallest segment at just 7%. Explorers are more likely than other segments to value the experiential aspects of studying in the U.S.

Highfliers: Students with high financial resources and high academic preparedness

Highfliers are the most sought-after international student segment. They have both the academic abilities to thrive in American HEIs and the financial assets to study without institutional support. The largest proportion of students in this category comes from China, where they comprise 35% of the population. For Highfliers, family support is key to their financial independence, as 69% indicated family or friends as their main source of funding.

Strivers: Students with low financial resources and high academic preparedness

Strivers constitute the largest segment of survey participants (31%). What this segment lacks in financial resources, it compensates for with strong academic abilities. Although 61% of Strivers indicated that they rely on institutional financial aid, they indicated more frequently than any other segments that they “very strongly” felt that they are academically prepared to enter an American institution of higher learning (82%).

Strugglers: Students with low financial resources and low academic preparedness

Strugglers constitute 16% of all survey participants. They may be highly motivated to attend an American HEI, but will have difficulty funding their studies, and will likely require academic support. Although Strugglers do not dominate any particular student population, institutions need to acknowledge the existence of this demographic as they are likely to require academic and financial support.

Differences by Level of Education

Nearly three-fourths of bachelor’s-seeking students have taken or plan to enroll in supplemental English language courses, as compared to 66% of those at the master’s level. They are twice as likely to list student services as their most pressing information need as are prospective master’s students. This suggests that institutions wishing to increase their enrollment of international students at the bachelor’s level should ensure that they have adequate student support services, particularly for English language learners.

The profile of students seeking master’s degrees differs significantly from that of students at the doctoral level. Explorers constitute only 10% of doctoral students but represent 24% of master’s students. Master’s students ranked admissions officers (33%), current students (16%), and family and friends (16%) as the three most trusted sources of information on studying in the U.S. Moreover, 46% of master’s students listed reputation as their most pressing information need. Institutions should leverage word-of-mouth sources such as student ambassadors and administrators to engage master’s students.

[5]China

[5]China

The share of Chinese Highfliers (36%) is larger than it is among Indians (22%) and Saudis (33%), indicating that this demographic is more likely to have the financial and academic resources needed to succeed in the American higher education system. Only 36% of Chinese respondents reported that they planned to use personal finances to fund their education, with the majority relying on the support of family and friends (77%).

Chinese students (31%) are more likely to seek information on studying abroad through online discussion forums as compared to Saudi (12%) and Indian students (24%). With high financial resources and career-oriented motives for studying in the U.S., Chinese students’ most pressing search need is related to post-graduation career prospects. Institutions interested in recruiting Chinese students need to engage parents and use local Chinese social media platforms such as SinaWeibo and Renren.

India

Of the top three countries, Indian respondents show the strongest academic record – 74% of them rank high in academic preparedness, compared to 51% of Chinese and 43% of Saudi respondents. Their comparatively robust English capabilities also make them an attractive source country for international recruitment among institutions that do not have the resources or infrastructure to fully support English language learners. Despite their academic prowess, Indian respondents rank the lowest of the three countries in terms of financial resources.

Indian students have a preference for word-of-mouth information sources such as family, friends, and alumni and seek information pertaining to finances and scholarship availability. Institutions wishing to increase their Indian student population should consider the use of student ambassadors and alumni in their marketing efforts and make sure to maintain a presence on career-oriented social media sites such as LinkedIn. They should also be transparent about the availability of scholarships for international students, and give detailed information on how to obtain these grants.

Saudi Arabia

In recent years, the number of Saudi students [6] in the U.S. has increased significantly, mostly due to government-funded scholarships. Our data supports this reality, finding that nearly three-fourths of Saudi students have high financial resources. As a result, the two largest Saudi segments are Explorers (39%) and Highfliers (33%). However, Saudi students also seem to have lower academic preparedness than Chinese and Indian students, with 58% falling into this category, primarily due to a lack of English language preparedness. We recommend that institutions wishing to recruit Saudi students make sure that they have the capacity to absorb a population that may have more limited English skills.

Saudi students are more likely to search for information on the geographic location of their prospective institution of higher education than Indian or Chinese students, a feature consistent with the profile of Explorers. Additionally, they reported the lowest use of social media. Schools wishing to recruit more Saudi students should highlight information about the experiential qualities of their institution on their marketing material, and of course, consider the influence of government funding bodies in Saudi students’ decision-making processes.

Agents in the Spotlight

Over the last few years, the implications of using commission-based recruiting agents (educational consultants) have increasingly come under scrutiny. Our research sheds new light on the agent debate, by elucidating an often overlooked proposition: different profiles of students use agents for varying purposes. Moreover, we found a large degree of variance regarding transparency in the student-agent relationship.

By a large margin, Chinese students paid the most for agent’s services, with half of those who paid for services reporting fees in excess of US$2,000. In contrast, only 3% of Indian students indicated that they paid more than $2,000.

Although students from China pay more than other students for educational consultants’ services, only 7% of Chinese respondents ranked them as the most trusted source of information, as compared to 12% of overall respondents.

An overwhelming majority of Indian students (93%) that used agents indicated that they did so to shortlist universities, whereas Chinese respondents are more likely to use educational consultants for application assistance (77%) and essay editing (65%).

Only 13% of respondents who had used education consultants knew that the agent would receive commission from institutions, 44% did not know, and 43% did not disclose this information. Indian respondents were the least likely to be aware of a commission-based practice – 60%, while 34% of Chinese and 31% Saudi respondents reported that they were unaware of such activity.

Our research elucidates two insights related to the use of agents in recruiting international students. First, international students who use agents differ in terms of their needs; and second, the lack of transparency is acute in the student-agent relationship. Institutions that use or plan to use agents should not only understand why international students use them, but set a high standard of transparency to make sure unethical practices are minimized.

Recommendations

1. Recognize the diversity of international students: International students differ significantly in terms of their motivations, needs and behaviors by level of education, source countries and demographics. Institutions cannot simply apply the same recruitment strategies for all international students. A granular understanding of segments is indispensable in a competitive and cost-conscious environment.

2. Adapt to the changing needs of students: International student needs and behaviors differ not only by different segments, but are also in constant flux. Many recruitment practices designed in the “pre-Facebook” era are still considered effective by some institutions, while student expectations have changed. Institutions need to re-evaluate their assumptions and adapt to the changing needs of students.

3. Deploy an analytics-driven framework to formulate international enrollment strategies: To better integrate the diversity of profiles and the changing needs of international students for informed strategies, institutions need to invest in and deploy a systematic framework of analyzing the enrollment funnel and regularly research student expectations and experiences.

Differences between international students permeate their information-seeking behavior and hence viewing all international students as the same results in ineffective strategies. Our intention with this research is to provide a framework for institutions to understand the different needs of international student segments and thus improve institutional strategies.

1. [7] Lederman, D. (2013, 07 12). CFO Survey Reveals Doubts About Financial Sustainability. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from http://www.insidehighered.com/news/survey/cfo-survey-reveals-doubts-about-financial-sustainability [1]