By Yoko Kono

You might be surprised to learn that one in four international students pursuing Australian degrees is studying outside Australia, and more than half [1] studying towards a UK degree are doing so outside the country. Today, these students electing to stay in their home country or region to pursue a foreign education—termed “glocal” students [2]—are growing at a faster rate than the more traditional mobile “global” student segment. While the provision of higher education beyond national borders, known as transnational education (TNE), is a well-established activity for British and Australian universities, U.S. higher education institutions (HEIs) have traditionally been far less active in this realm.

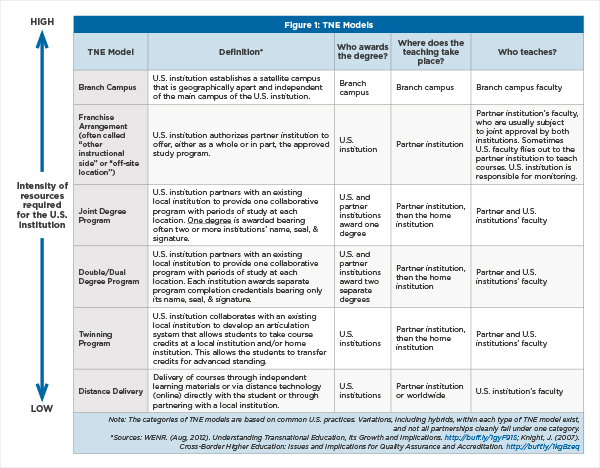

TNE is broadly defined by UNESCO and the Council of Europe [3] as, “all types of higher education study programs, or sets of courses of study, or educational services (including those of distance education) in which the learners are located in a country different from the one where the awarding institution is based.”

Branch campuses are the most visible example of transnational education, yet they account for just a small portion of global activity. Furthermore, due to the high start-up costs and inherent risks associated with creating a sustainable infrastructure, as well as concerns over academic and political freedom in certain countries [4], global growth in branch campuses is slowing down [5]. Other types of institutional arrangements, such as franchising, dual/joint degree, and twinning programs are where market opportunities are currently thriving.

U.S. HEIs that seek to provide TNE opportunities can engage in a wide range of models. Western Michigan University [7] and Drexel University [8] are examples of institutions with a variety of TNE arrangements (refer to other cases in the interactive map below). While double and joint degrees are the common models [9] of TNE among U.S. HEIs, they could also consider more affordable alternatives such as MOOCs [10] and distance education [11], which are growing in demand among international students.

Institutions looking to expand their internationalization activities through transnational education must determine the best fit TNE model(s) for their institution, while identifying suitable institutional partners that fit their long-term internationalization goals. They also need to make sure they fully understand the nature of the relationships they are entering into as relates to broader priorities and institutional capabilities. Furthermore, U.S. HEIs must consider the varying implications of TNE programs, including which institution will provide and manage the academic program and curriculum, teaching and faculty, recruitment and marketing, and quality assurance and oversight. The extent to which partner HEIs address and manage these parameters will go a long way to defining the nature and likely success of the partnership. As case studies have shown, accurate assessment and management of TNE activities are crucial for long-term sustainability, monetary and reputational return on investment, and global impact.

Previous Mobility Monitors

- Could Canada’s International Enrollment Growth Go Cold? [12]

- Segmentation to Understand Prospective International Master’s Students [13]

- On the Rise: Turkey’s Need and Desire for Overseas Education [14]

WES in the News

- Bullies in Admissions [15], Inside Higher Ed

- What’s Next in Student Recruitment for the Year Ahead? [16] The PIE News

- 10 Colleges With the Highest Percentage of Students in ESL [17], U.S. News & World Report