By Nick Clark, Editor, World Education News & Reviews

Introduction

Indonesia is the world’s fourth most populous country and third-largest democracy. The archipelago of over 18,000 islands is home to more than a quarter million people, of whom 86 percent identify as Muslims making it the world’s biggest Muslim-majority nation. Demographically, the nation is young, has a growing middle class, and does not face the issues related to ballooning elderly populations confronted by countries such as Japan and South Korea. The economy is the biggest in Southeast Asia and it has been enjoying strong GDP growth of between 5.0 and 6.5 percent for over a decade. Observers predict [3] that the number of families with household incomes exceeding US$10,000 will double by 2020, while average disposable incomes are expected to increase at 3-5 percent annually.

All these factors combine to make Indonesia of particular strategic importance to regional neighbours, in addition to global partners in the West. The current U.S. administration has made cooperation with Indonesia one of its foreign-policy priorities, and educational collaboration is a significant part of that engagement plan. During her visit to Indonesia in 2009, then Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton made reference to educational collaboration and exchange with Indonesia as being among one of the essential steps toward boosting academic mobility between the two countries and an important means of furthering the United States’ commitment to “smart power.”

In anticipation of increased and rejuvenated academic mobility and cooperation between the United States and Indonesia, World Education Services, through the Knowledge Resource Exchange, [4] will be offering a free webinar [5] on April 11 designed to help international education professional evaluate Indonesian academic credentials.

In this article we offer a hardcopy companion to that webinar, while also looking at some of the challenges currently facing the Indonesian education system. We also take a look at current and future trends in international academic mobility to and from the country.

Educational Challenges

Despite recent economic growth and significant demographic advantages, Indonesia faces sizable challenges in educating its huge population. The Boston Consulting Group released a report [8] in May 2013 suggesting that Indonesian companies will struggle to fill half of their entry-level positions with fully qualified candidates by the end of the decade due to low upper secondary and tertiary enrollment rates and substandard quality standards. The engineering field is expected to experience the worst shortages, with the shortfall of engineering graduates projected to increase to more than 70 percent in 2025 from a 40 percent shortage in 2013. And while the report suggests that shortages will not be as severe at senior levels, it says that many at that level will lack the global exposure and leadership skills needed to succeed.

In 2011, the gross enrollment ratio (GER) at the tertiary level (total tertiary enrollment as a percentage of the college-age population) was 25 percent (UNESCO, 2013). This is a lower percentage than all BRIC nations with the exception of India (20 percent), lower than the global average (31 percent) and lower also than most members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations [9]. Nonetheless, the number of graduates in the country doubled between 2005 and 2012, according to data from the British Council, while the GER has risen significantly from just 12 percent a decade earlier (2001) . And the government is focused on increasing access further, setting a goal of enrolling one quarter of the Indonesian college-age population in an institution of higher education by 2020. This represents an approximately quarter million annual increase in students over the next decade.

While enrollment figures through the first nine years of basic education have also improved significantly in recent years, at the upper secondary level just 51 percent of the population aged 15-18 attended school in 2012, well below the Southeast Asian average of 65 percent. This is despite the fact that the government is constitutionally obligated to direct 20 percent of the national budget towards education, something observers say does not happen in reality. Official figures for 2010 put education expenditures at 17.1 percent of the national budget, which represents 3 percent of GDP, low comparative to most neighboring countries. Waste through corruption is considered a major issue within the Indonesian education system.

As a consequence, quality standards at the secondary and tertiary level are well below global standards as measured by a number of different indicators. According to the results of the 2012 Program for International Student Assessment [10], 15-year-olds in Indonesia were rated 64th out of 65 countries in mathematics, science, and reading.

Indonesian universities have also performed poorly in international university rankings. The Times Higher Education [11] rated no Indonesian institutions among its top 400 global universities or top 100 Asian universities in 2013. Likewise, the Shanghai Jiao Tong Ranking reported no Indonesian universities among its global top 500 [12]. The QS World Ranking [13], on the other hand, lists the University of Indonesia 64th in Asia (309th globally), the Bandung Institute of Technology 129th (461-470 globally), Universitas Gadjah Mada 133rd (501-550), and Airlangga University 145th (701+).

Indonesia finished bottom out of 50 countries in the 2013 edition of the Universitas 21 ranking [14], which grades national higher education systems on investment, research output, gender balance, international connectivity and other measures. It scored particularly poorly on the first two metrics.

Data from Indonesia’s Directorate General of Higher Education [15] shows that there is significant inequality in the distribution of institutions throughout the country, with poorer regions having the fewest institutions of higher education, and a number of provinces within these regions having no public institutions at all. As an archipelago of more than 18,000 islands, distributing educational opportunities evenly is a tough task, especially with an estimated 700 different languages spoken across the country.

A Focus on Vocational Training

In light of the many challenges facing the tertiary sector, alongside the rapidly increasing demand for tertiary places and the unmet needs of the labor market, the Indonesian government is currently focused more on expanding vocational programs than it is traditional academic training.

To help achieve this, the government is committed to developing a network of institutions based on the U.S. community college model. Unlike the low-cost training provided by currently existing Indonesian polytechnics, credits from community colleges will be transferable to a university, thus offering graduates opportunities to further their vocational training at a higher level.

The government is working to establish 500 community colleges within the next four years. More than 30 have already been established with a similar number ready to open soon. These colleges are largely focused on training for jobs in manufacturing, nursing, automotive technology and other trades. The government is also supporting universities looking to establish a generation of technical colleges.

At the secondary level, the government has set a target of 50 percent upper secondary enrollment in vocational schools by 2015 and a ratio of 70:30 by 2025. In 2010, 41 percent of upper secondary students were enrolled in technical and vocational schools, up from 33 percent in 2007.

International Mobility

Competition for places at Indonesia’s best public universities is fierce. In 2010, 447,000 students sat for the National University Entrance Examination, with just 80,000 seats available. In conjunction with rising prosperity and a growing middle class, increased – and unmet demand – for university places is likely to lead to increasing numbers of students looking overseas for tertiary study options.

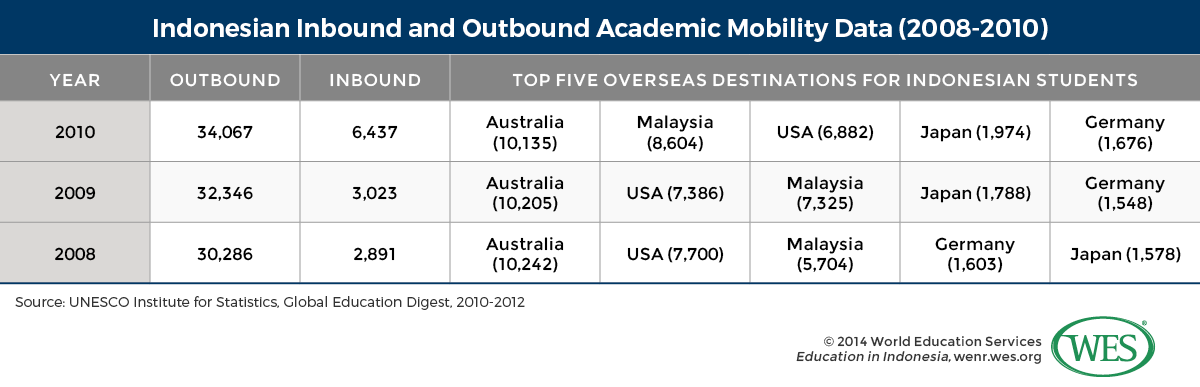

And some say the number is likely to grow quickly, even if from a low base of 34,067 worldwide in 2010 (UNESCO, 2012). Currently the number of outbound Indonesian students account for less than one percent (0.7%) of all Indonesian tertiary students, very low compared to global averages; and inbound rates are even lower.

In 2012, the British Council estimated that growth in the number of internationally mobile Indonesian students would average 20 percent in the coming years, stating that Indonesia will be one of the world’s “major international education markets in the next few years.” The Council’s 2012, Going Global report: The Shape of Things to Come [16], predicts that the number of Indonesians in higher education will grow by a total of 2.3 million to 7.8 million students by 2020, making it the fifth largest system in the world after China, India, the United States and Brazil.

Simply put, the British Council believes that Indonesian institutions of higher education will not be able to meet burgeoning demand in the coming years, so an increasingly affluent middle class will be forced to look at options offered internationally.

Currently, Australia is the number one choice for Indonesians abroad, largely due to geographic proximity, perceived institutional quality, and English-medium instruction. Australia Education International reports that there were 17,131 Indonesians studying in Australia in 2013, mainly at the tertiary level, and representing the eighth largest source market for Australian institutions of higher education.

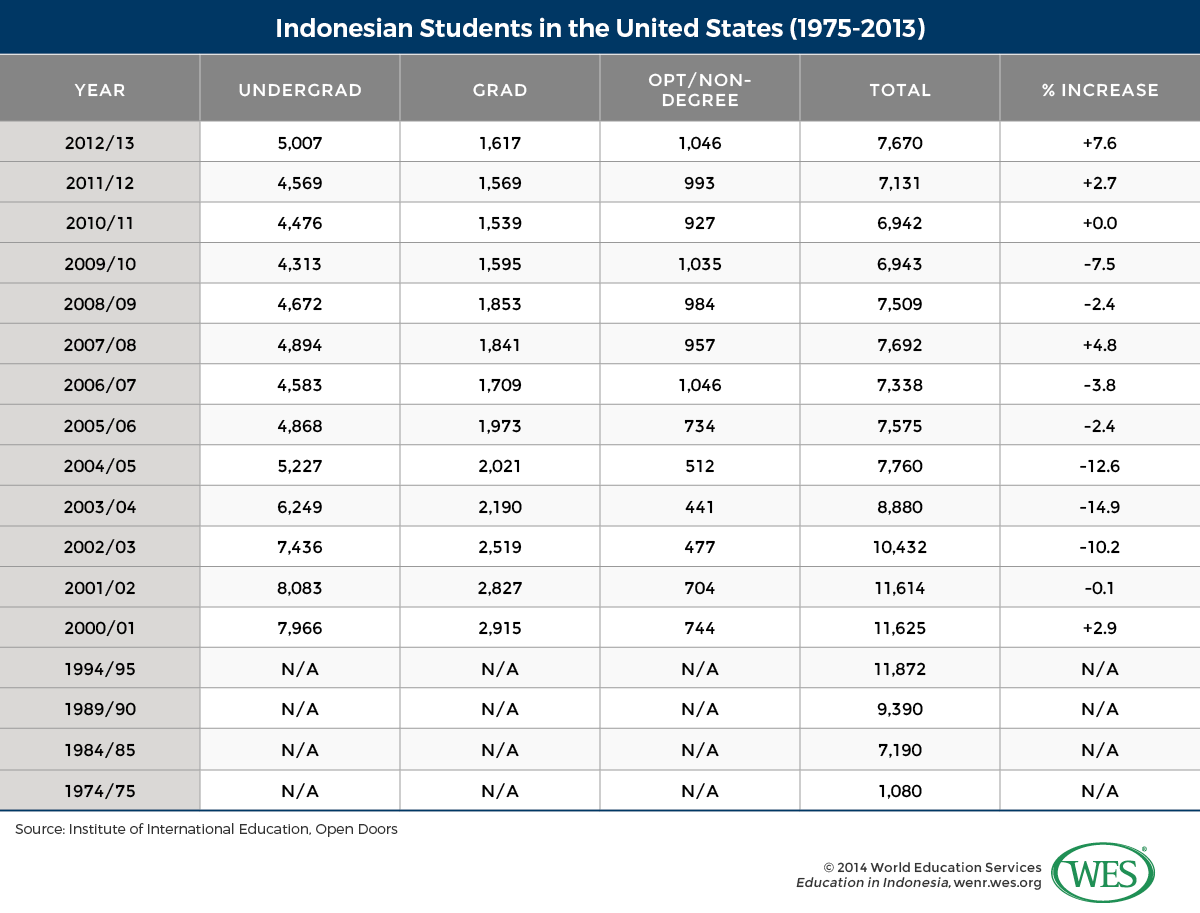

The third-most popular destination, the United States, has seen a resurgence in the number of Indonesian students entering its universities in the last couple of years after a fairly precipitous decline in the 10 years prior. After a period of steady growth in the 1980s and 1990s, peaking in 1997/98 at 13,282 students, Indonesian enrollment numbers have tailed off steadily, with especially large declines seen in the three years following the 2001 World Trade Center attacks. Enrollment numbers in 2010/11 were the same as they were in 2009/10 at just under 7,000 and have since grown to 7,670 in 2013, ranking Indonesia as the 18th leading place of origin for students coming to the United States.

Cost, distance and lingering fears about visa denials in the post-9/11 era have all contributed to making the United States less attractive as a study destination, especially in the face of increased competition and marketing efforts from regional competitor destinations. The PIE News reported recently that “China, Malaysia and Singapore have latterly been joined by New Zealand in announcing their intention to attract more Indonesian students. China, in particular, increased scholarships in the country after witnessing a 42 percent enrollment surge at its universities in 2007-2009.”

Malaysia became the second-most popular destination for Indonesian students in 2010, according to UNESCO data, which is reflective of an Indonesian focus on affordability and cultural similarities.

The British Council has also pinpointed Indonesia as a country that has great potential with regards to transnational education (TNE) provision, despite currently having a legislative framework that has “not proved conducive to facilitating TNE initiatives from overseas providers.” The British Council predicts that, “Indonesia will become [an] increasingly important player in the global tertiary education sector,” with “significant TNE opportunity” in the near-term future. Specifically, the British Council suggests that the best, perhaps only, way into the domestic Indonesian education market is in partnership with local institutions.

The Future of US-Indonesia Academic Mobility

Despite the recent declining enrollment trend among Indonesian students in the U.S., there are reasons to believe that a reversal is imminent, if not already underway. Primary among these reasons is an initiative launched by President Barak Obama and Indonesian officials in November 2010 to double the current number of Indonesians studying at U.S. institutions by 2015 to 15,000, and to significantly increase educational opportunities in Indonesia for U.S. students.

Both President Obama and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called for increased collaboration in education between the two countries on separate trips to Indonesia in 2010 and 2009. During President Obama’s visit, he and Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono announced the U.S.-Indonesia Comprehensive Partnership [19], a long-term commitment to broadening, deepening, and elevating bilateral relations between the United States and Indonesia, with a priority placed on higher-education cooperation.

In the interests of meeting the goal of increasing academic mobility between the two nations, a “Joint U.S.-Indonesia Council for Higher Education Partnership [20]” was formed to allow institutions of education to work in coordination with the two governments. The Council, which was endorsed by both presidents at their 2010 meeting, has been established to advise the U.S. academic community about U.S. or Indonesian government funds that are, or which may become, available. In addition, it is working with U.S. institutions of higher education and other Council participants to develop solutions that will lower the cost of a U.S. education for Indonesians, and make studying abroad in Indonesia more attractive to Americans.

Under the governmental Partnership agreement, a plan of action was agreed to by the two governments, with priorities including: Study abroad for students from both countries, joint degree programs, university partnerships and mutual recognition of academic degrees and certificates, and a strengthening of cooperation in science, technology and innovation.

The Council believes that government and current private efforts will achieve 3,000-4,000 of the aimed increase in Indonesian student numbers. Therefore, it points to the need for engineering a way of enabling the remaining 3,000-4,000 by the end of 2015. This, it says, “will include innovative ways to lower the cost of a U.S. education, guarantee student loans by governments, achieve a higher percentage of Indonesians in international student enrollments on U.S. campuses, better prepare Indonesians for U.S. study, and better market U.S. educational institutions in Indonesia.”

The Institute for International Education [21] has been leading another effort, funded by the U.S Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA), that in 2010 saw leaders from six U.S. colleges and universities and six Indonesian universities meet in Indonesia to take part in a workshop and study tour focused on strengthening higher education ties between the two countries. The tour was part of the U.S.-Indonesia Partnership Program (USIPP), [22] a two-year initiative sponsored by the ECA to increase the number of U.S. students who study abroad in Indonesia. The initiative led to the launch of the USIPP Consortium [23] in 2013, which will continue the work of the original two-year partnership program.

Education System

Overview

The Indonesian education system is based on a 12-year school structure (6+3+3) followed by four years at the undergraduate level and two years at the master’s level for students pursuing non-vocational studies.

Education is compulsory for the first nine years (primary and junior secondary), and Islamic education is offered at all levels. The language of instruction is Bahasa Indonesia, but local regional languages may be used in the first three years of primary school. The school year runs from mid-July to mid-June on a semester system.

Alongside the general education system, there are also Islamic schools or madrasahs. Islamic primary, lower and upper secondary schools are known as Madrasah Ibtidaiyah (MI), Madrasah Tsanawiyah (MT), and Madrasah Aliyah (MA), respectively. Technical and vocational education within the Islamic school system, known as Madrasah Aliyah Kejuruan (MAK), is also provided. Madrasah schools follow the same 6-3-3 system structure as in general education.

The Ministry of National Education [24] and Ministry of Religious Affairs [25] have oversight of secondary, vocational and higher education, including state and private religious schools, which must adopt core curriculum developed by the Ministry of National Education. The Ministry of Religious Affairs primarily oversees the religious components of Islamic curricula.

Primary Education (sekolah dasa – SD)

Primary schooling begins at the age of six for most children and is compulsory for all. The six-year curriculum includes: Civics and religious education, moral education, Indonesian history, Bahasa Indonesia (national language), mathematics, science, social studies, physical education, and art.

Students graduate with the Certificate of Graduation (Surat Tanda Kelulusan – STK) after taking a school-administered final examination.

In 2010, 83.2 percent of all children in primary education were in public schools.

Junior Secondary Education (Sekolah Menengah Pertama – SMP)

Junior secondary schooling is three years in length (grades 6-9) and the curriculum includes: Pancasila (civics), religious education, Bahasa Indonesia, English language, mathematics, biology, chemistry, physics, economics, geography, history, art, and physical education.

Students graduate with the Certificate of Completion of Junior Secondary Education (Surat Tanda Tamat Belajar: Sekolah Menengah Pertama – STTB: SMP or Ijazah: SMP), which is issued by the school attended.

In addition, the Certificate of Graduation (Surat Keterangan Hasil Ujian Nasional – SKHUN) is issued to students who pass the National Examination (Ujian [Akhir] Nasional – UN/UAN) set by the Department of National Education at the end of grade 9. Students are tested in mathematics, English, Bahasa Indonesia, and sciences. Results are indicated on the certificate.

In 2010, 63.7 percent of lower secondary students were in public schools.

Upper Secondary Education (Sekolah Menengah Atas – SMA)

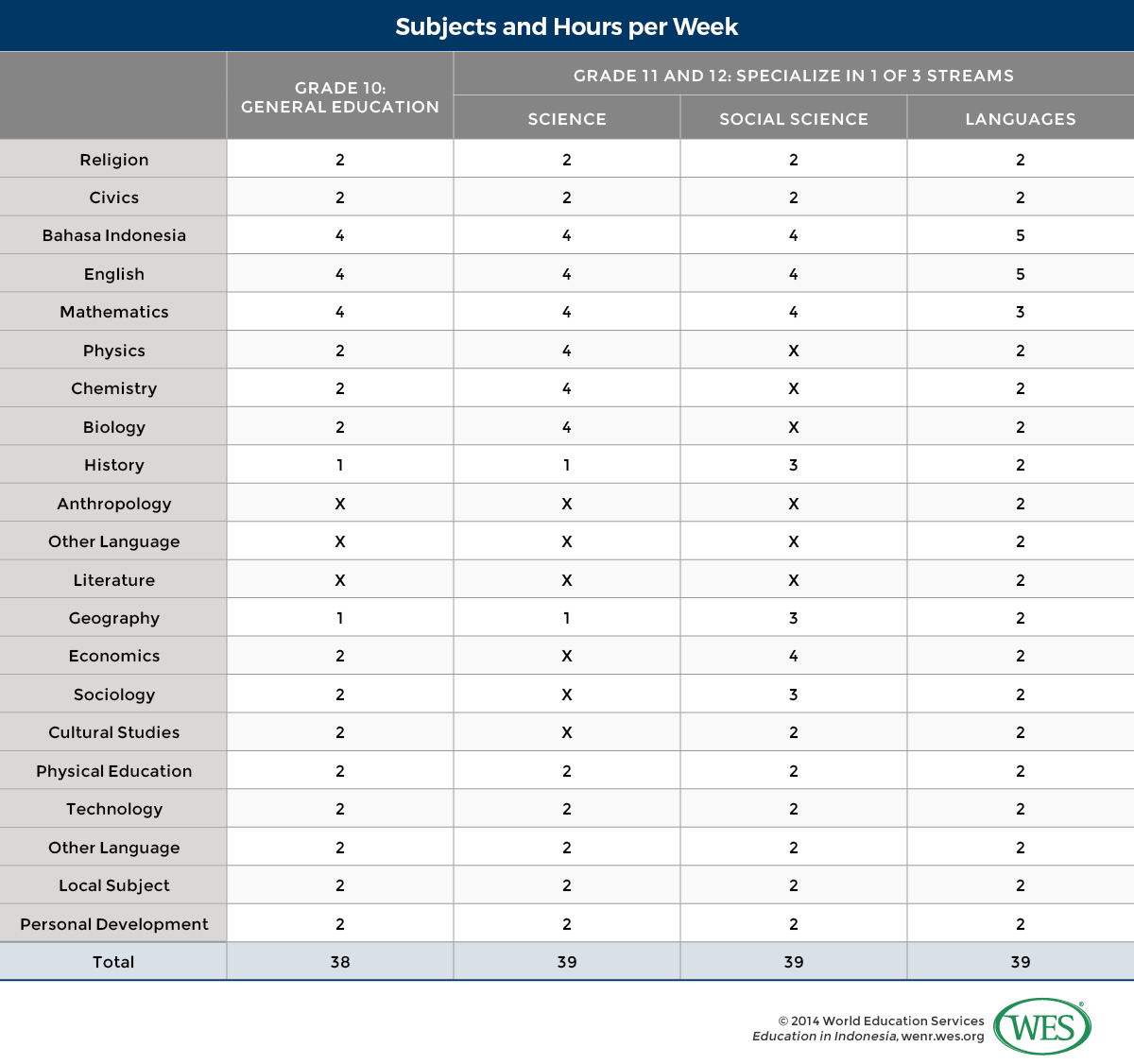

Upper secondary education is three years in length (grades 9-12), with the first-year curriculum being more generalist than the last two. Students join either the general academic (Sekolah Menengah Atas – SMA) or vocational stream (Madrasah Aliyah Kejuruan – MAK) upon entry into upper secondary.

From the second year of the general academic upper secondary stream, students specialize in one of four discipline groups, while also continuing to study core subjects:

- Natural Sciences

- Social Sciences

- Languages

- Religion (at madrasah schools)

The stream or discipline chosen by students will generally determine the field of study that they apply for at the higher-education level, should they chose to further their studies, although the emphasis on specialization has been lessened over the last decade.

In 2010, 50.2 percent of upper secondary students were enrolled in public schools. The majority of madrasah and religious schools are private. Private schools are required to comply with national education regulations in the areas of curriculum, educational calendar, teaching load and teacher quality standards. Students that pass the National Examination receive graduation certificates equivalent to that of general secondary school students.

Curriculum

Technical and Vocational Upper Secondary (Madrasah Aliyah Kejuruan – MAK)

The Indonesian government is currently trying to increase enrollment in the secondary technical and vocational stream, in response to the need for middle-level skilled workers in the growing economy. The government has set a target of 50 percent upper secondary enrollment in vocational schools by 2015 and a ratio of 70:30 by 2025. In 2010, 41 percent of upper secondary students were enrolled in technical and vocational schools, up from 33 percent in 2007.

Technical and vocational education is offered only at the upper secondary level in both general and religious schools. Schools must follow the national curriculum, but are encouraged to develop a curriculum to meet the needs of the local economy. Technical education is offered in six broad streams: Technology and engineering; information and communication technology; community welfare, arts, crafts, and tourism; agribusiness and agro-technology; and business and management. These fields can be further divided into 40 programs and 121 competencies.

Although students in technical and vocational institutions can transfer to general secondary programs, it does not happen commonly.

Graduation Requirements

Secondary School Exams

Secondary school examinations are administered by individual schools and held before the National Examinations. Grades from the final year of study are shown separately on the student’s school report.

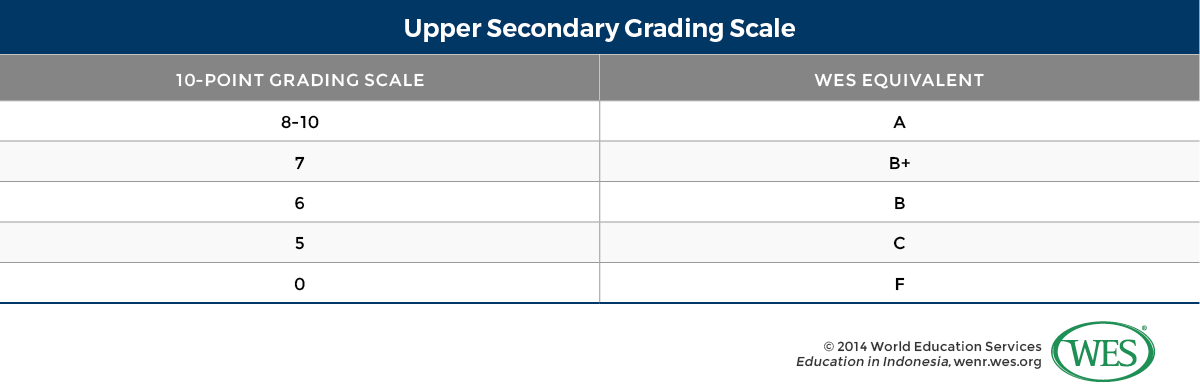

To pass the examinations an overall average of 6 is required (4.26 minimum for individual subjects). The exception is for key schools, where the minimum pass mark is 6 in each subject.

National Examinations (Ujian Nasional)

The National Examinations are administered by the Ministry of National Education. To pass the exams, an overall average of 6 is required (4.26 minimum for individual subjects). Students are tested in the following streams:

- Natural Science (mathematics, Bahasa Indonesia and English)

- Social Science (Bahasa Indonesia, English and economics)

- Language (Bahasa Indonesia, English and another foreign language)

Qualifications

The Secondary School Certificate of Completion (Ljazah, or Surat Tanda Tamat Belajar Sekolah Menengah Atas – STTB: SMA) details scores from the final school exams and guarantees that the student has completed secondary school. This document is issued by the school attended.

The Certificate of Graduation (Surat Keterangan Hasil Ujian Nasional – SKHUN) is issued to students who pass the National Examinations. This document is required for admission to higher education, and is issued by the Ministry of National Education.

Admission to Higher Education

General Requirements

- Secondary School Certificate of Graduation (and, by default, the Certificate of Completion)

- National University Entrance Exam (Seleksi Penerimaan Mahasiswa Baru) for entry to public universities

- Private universities have their own entrance examinations

- Polytechnics (politeknik) and academies (akademi) set their own entrance exams, which are open to students with a Secondary School Certificate of Graduation.

Competition to study at public universities is very high, and subsequently the admissions examinations are highly competitive. These tests tend to favor students with the means to take preparatory classes.

In 2010, 447,000 students sat for the National University Entrance Examination, with just 80,000 seats available. By law (2010), 60 percent of freshman seats are reserved for top-scoring candidates on the admissions examination, which is centrally administered by the Ministry of National Education and takes place on the same day at all public universities across the country. The remaining 40 percent of the seats are distributed according to individual admissions criteria/exams set by each university. Many public universities give priority to students from their province or district.

Higher Education

According to the Directorate of General Higher Education, in 2009 there were 3,016 institutions of higher education in Indonesia, an increase of 28 percent from 2005 when there were 2,428 institutions. In 2010, 58 percent of students were enrolled in private institutions of higher education.

Types of Institutions

- Universities (private and public). Oversight and recognition through the Ministry of National Education. In 2009, there were 460 universities, over 400 of which were private.

- IKIPS (Institutes and Teacher Training Institutes), which rank as universities with full degree-granting status, but across a specialized field of studies. In 2009, there were 54 institutes.

- Islamic Institutes. These have the same rank as universities but under the auspices of the Ministry of Religious Affairs.

- Colleges, or Advanced Schools, (Sekolah Tinggi) offer academic and professional university-level education in one particular discipline. In 2009, there were 1,306 colleges

- Single-Faculty Academies offering diploma/certificate technician-level programs only. In 2009, there were 1,034 academies.

- Polytechnics are attached to universities and provide sub-degree junior technician training. In 2009, there were 162 polytechnics.

- Community Colleges offering two-year programs with credits that are transferable to university programs, similar to the U.S. model. Community colleges are a recent addition to the Indonesian higher education system and are being introduced in a bid to meet rapidly increasing demand for skilled workers among Indonesian employers. The government hopes to open as many as 500 community colleges across Indonesia in the next four years.

Diplomas and Degrees

- The Diploma (Diploma I – Diploma IV) requires one to four years of full time study, or 40-160 credits depending on program length. The title of the Diploma (I-IV) generally indicates, in years, the length of the program. The D-II award is offered mainly in education, while the D-III award is the most common and is offered across a broad spectrum of disciplines. D-11 and D-III programs are typically offered at polytechnics. The D-I and D-IV are offered in a limited number of fields, and the D-IV (or Sarjana Sains Terapan – SST) is considered a degree-level program akin to a bachelor of applied science.

- The Bachelor’s Degree (Sarjana 1) requires four to five years of full time study, or 144-160 credits, with courses in the student’s major beginning in the first year. Longer programs are typically in professional fields such as medicine, dentistry and pharmacy, and allow awardees the right to practice, although extra requirements may be needed in health fields.

- The Master’s Degree (Magister or S2) requires two years of full time study, or 36-50 credits, and the completion of a thesis.

- The Doctor of Philosophy (Doktor or S3) requires a minimum of three years or 48-53 credits, and the defense of a dissertation.

Teacher Education

Primary school teachers are trained at IKIPs where they follow two-year programs leading to the award of a Diploma (D2) following upper secondary education.

Junior secondary school teachers are trained at the tertiary level in two- or three-year programs at IKIPs leading to the award of a Diploma (D2 or D3).

Upper secondary teachers are required to hold Diploma III Kependidikan (Education) or a Bachelor’s Degree for the Sarjana (S1).

According to the Teacher Law of 2005, all new teachers will be required to hold a four-year higher education degree (diploma or bachelor) by 2015

Recognition

The National Accreditation Agency for Higher Education [28] (Badan Akreditasi Nasional Perguruan Tingi, BAN-PT) is responsible for performing program quality assurance audits in both the public and private sectors. Programs are rated on a scale of A to D, with programs rated A or B accredited for five years and those rated a C for three years. Those rated D have five years to improve or face risk of closure.

A searchable directory of accredited programs and their ratings is available through the BAN-PT website. In the search fields ‘Tinggi’ refers to the name of the institution and ‘Studi’ the name of the program.

WES Document Requirements

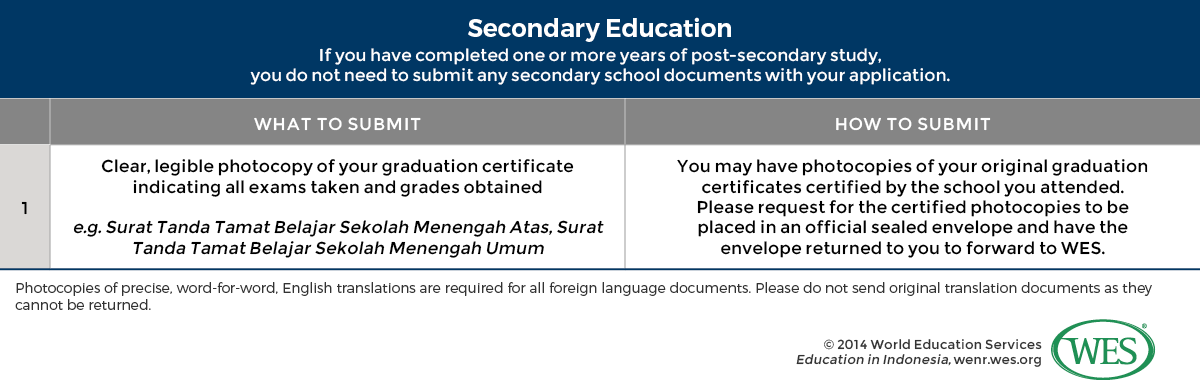

Secondary Education

WES requires that a copy of the graduation certificate indicating all exams taken and grades obtained be sent to WES directly from the secondary school attended.

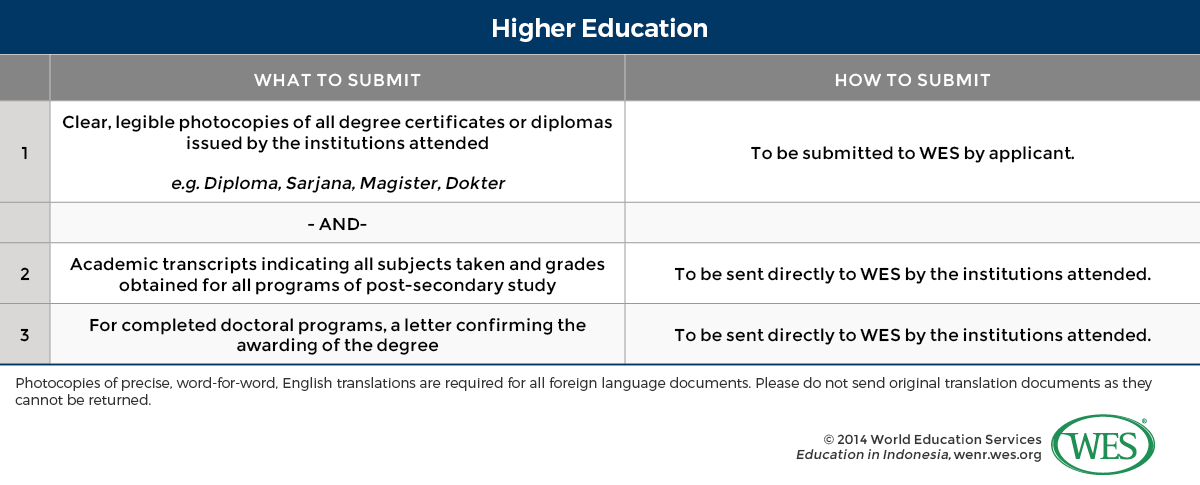

Higher Education

WES requires a photocopy of the degree or diploma in addition to the academic transcripts indicating all subjects taken and grades obtained. The transcript must be sent directly to WES by the institution attended.

If official documents are issued in Bahasa Indonesia, WES requires a precise word for word English translation.

Sample Documents

This file of Sample Documents [32] (pdf) shows a set of annotated credentials from the Vietnamese and Indonesian education systems. Indonesian sample documents begin on page 22:

- High School Graduation Certificate (original and English translation)

- High School Examination Results (with translation)

- Bachelor Degree Transcript

- Bachelor Degree Certificate

- Master Degree Transcript

- Master Degree Certificate

For a more in-depth discussion of the documents seen here, WES is offering a free interactive webinar [5] on April 11.