Nick Clark, Editor, World Education News & Reviews

In this article we offer a guide to the education system of Malaysia, with insights on the challenges currently facing the system and the reforms that have been outlined to improve it. In addition, we touch on mobility trends to and from Malaysia, before offering a comprehensive overview of the structure and credentials of the education system. Included in this overview is a file of sample academic documents, advice on what credentials to request when evaluating Malaysian student applications and how best to convert Malaysian grades.

Challenges

Enrollments at the primary and lower secondary levels are nearly universal in Malaysia and recent gains in pre-primary education have been noteworthy, according to a recent report [3] from the World Bank. However, relatively few students continue on to complete postsecondary education, with just 37.2 percent of the relevant age group completing upper secondary (Form 6 or equivalent), and 15.3 percent of 25-29 year olds in 2012 holding a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Spending on education is considered adequate by the World Bank and does not appear to be hindering improvements to the system. Expenditure on basic education is more than double that of other ASEAN countries; however, according to the results of 2012 PISA testing, regionally Malaysian students outperform only their Indonesian peers and lag behind lower income countries like Vietnam quite substantially. This despite enrollment levels equal to those of developed economies in the region.

The key constraints to improving the quality of basic education therefore relates to institutions, the World Bank surmises, specifically pointing to a lack of autonomy and shortcomings in teacher training and recruitment. By way of example, the World Bank describes Malaysia as having one of the most centralized education systems in the world, with over 65 percent of schools reporting that the selection of teachers for hiring takes place at the national level, compared to just over 5 percent in South Korea. The story is much the same for budget allocations within schools, student assessment and choice of textbooks. All this means that schools struggle to respond to local needs as policy is being dictated from the center.

Education Blueprint

The Government launched the Malaysia Education Blueprint [4] in 2013 to define the course of education reform over the next decade and to respond to many of the challenges faced by the system. The Blueprint sets a number of ambitious goals, including:

- Universal access and full enrollment of all children from preschool to upper secondary school by 2020.

- Improvement of student scores on international assessments such as PISA to the top third of participating countries within 15 years.

- Reduce by half the current urban-rural, socio-economic and gender achievement gaps by 2020.

To help achieve these goals, the Blueprint identifies a number of reforms that need to be implemented. These include:

- Increasing compulsory schooling from six to 11 years.

- The introduction of a Secondary School Standard Curriculum or Kurikulum Standard Sekolah Menengah (KSSM) and revised Primary School Standard Curriculum or Kurikulum Standard Sekolah Rendah (KSSR) in 2017 with greater emphasis on promoting knowledge and skills such as creative thinking, innovation, problem-solving and leadership.

- The introduction of clear learning standards so that students and parents understand the progress expected within each year of schooling.

- The introduction of English as a compulsory subject within the school leaving examination (SPM) from 2016, and an additional language by 2025.

- Increase entry standards for future teachers from 2013, requiring them to be among the top 30 percent of graduates.

- The definition of clear performance benchmarks (“system aspirations”) that will help measure progress of the reforms with annual reviews.

International Student Mobility

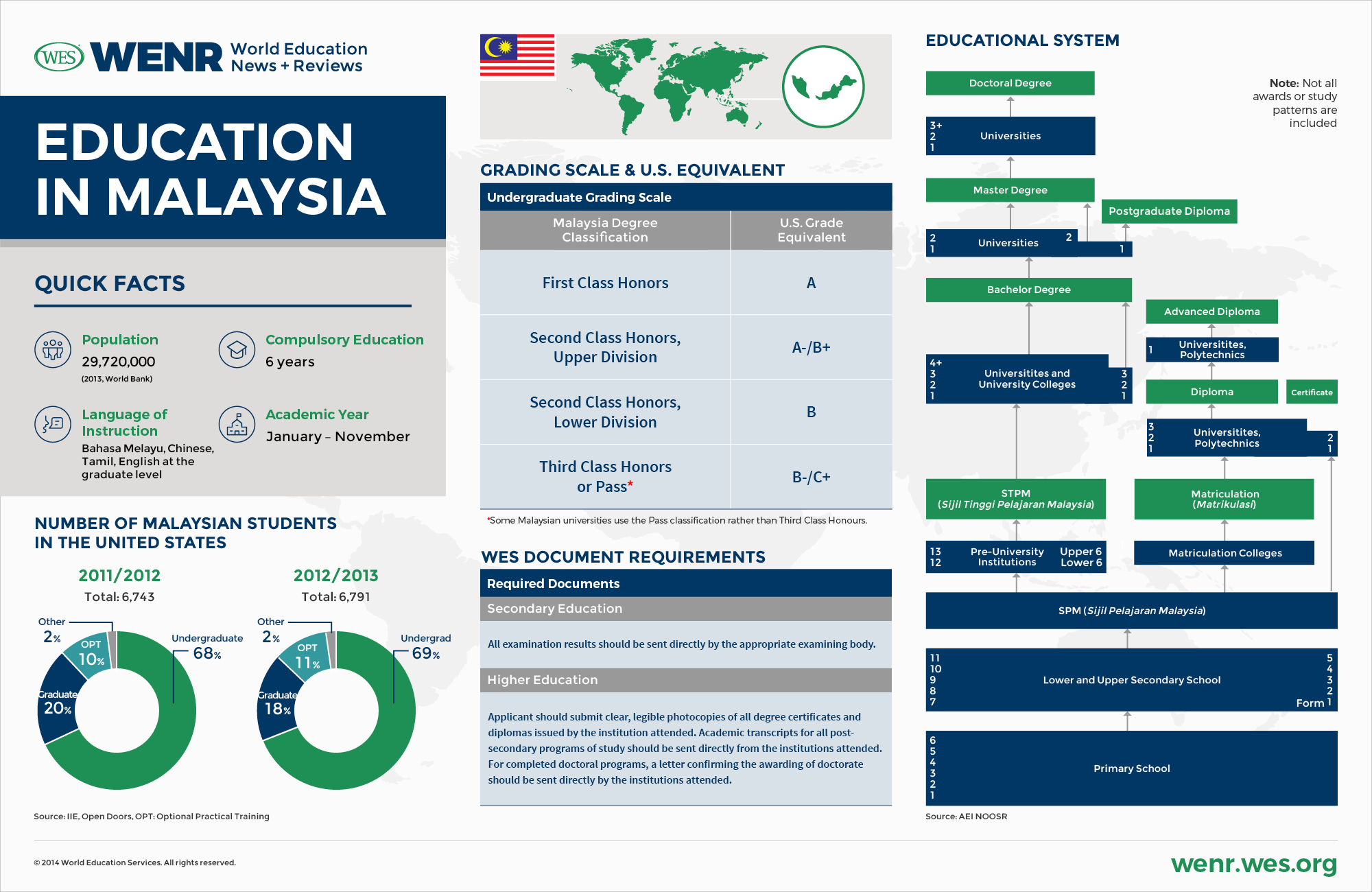

Malaysia is both a big sender and big receiver of international students, although inward and outward mobility numbers have been heading in opposite directions in recent years. In 1995, for example, 20 percent of all Malaysian students at the higher education level were studying abroad, mainly on government scholarships to the tune of an estimated US$800 million annually. Prior to the Southeast Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, there were more than 100,000 Malaysian students abroad, mainly in the UK and the U.S, but funding for scholarships was cut dramatically after the crisis, and in 2010 there were fewer than 80,000 Malaysians studying internationally (World Bank, 2013). In the United States alone, there were less than half the number of Malaysian students in 2010 than the 13,617 who were here in 1996, and while the numbers have crept up slightly since 2010 they are still less than half the 1996 total.

In response to the financial crisis, the Malaysian government redirected funding to domestic provision, significantly increasing the number of universities and colleges – both public and private – and introducing initiatives designed to transform the country into a developed knowledge-based economy. The government also encouraged the building of partnerships with foreign institutions of higher education. The goal of this internationalization strategy was twofold: to offer more educational opportunities for Malaysians domestically through transnational education programs and to attract international students. Ultimately, the government wants to establish the country as a regional hub for higher education in Southeast Asia, with a goal of attracting 200,000 international students by 2020.

To this end, regulations were changed in 1996 to allow for the establishment of foreign branch campuses on Malaysian soil, a move that complemented reforms from the previous decade that allowed private providers to confer degrees in partnership with foreign universities. As a result, private providers in Malaysia offer a large number of programs through franchise and twinning arrangements with foreign universities. In addition, nine foreign branch campuses currently have operations in the country while six Malaysian universities also have operations abroad.

Today, Malaysia is among the biggest markets for transnational education (TNE) provision and the biggest overall for UK providers with some 48,225 students studying towards a UK qualification in Malaysia in 2010, almost four times the number of Malaysian students in the UK. According to the Malaysian Qualifications Authority [5], there were a total of 563 accredited foreign programs (15 percent of all programs in Malaysia) in 2012. The top three countries providing TNE programs are the UK, Australia and the United States.

Currently, there are close to 100,000 international students enrolled in Malaysia-based institutions of higher education, more than double the 2007 total. The top five places of origin in 2010 were Iran (11,823), China (10,214), Indonesia (9,889), Yemen (5,866) and Nigeria (5,817). The large number of students from Islamic countries and Africa is due in large part to cultural and religious similarities and lower fees compared to universities in Europe and the United States. The appeal of Malaysia as an international study destination among Muslim students has also picked up significantly since the beginning of the ‘Arab Spring’ in 2010.

Among Malaysian students abroad, the top destination countries in 2010 were Australia (20,943), the United Kingdom (13,796), Egypt (8,611), the United States (6,100), and Indonesia (5,588), according to information [6] supplied to the Institute of International Education by the Ministry of Higher Education.

Education System

Language of Instruction

Bahasa Melayu is the primary language of instruction in Malaysian public schools. In 2003, the government introduced a policy of using English as the language of instruction for science and mathematics; however, this policy was discontinued in 2011. English is taught as a second language in both primary and secondary schools. In Chinese and Tamil national-type primary schools, Bahasa Melayu is taught as a second language and English is taught as a third language.

In public universities, the language of instruction in Bachelor Degree programs is Bahasa Melayu except for subjects related to science, mathematics and computing and IT subjects, which are generally taught in English. Most graduate studies are also conducted in English. In private higher education institutions, English is usually the language of instruction.

Academic Year

The school year runs from January to November. In higher education, subjects are usually taught over semesters rather than years. Some universities have a third semester of 8-12 weeks, allowing students to complete programs in a shorter time.

School Structure

The school system is structured on a 6+3+2+2 model, with six years of compulsory primary education beginning at age seven, followed by three years of lower secondary education, two years of upper secondary, and two years of pre-university senior secondary study.

Primary

Enrollment at the primary level has been nearly universal for decades while secondary enrollment has also expanded rapidly in recent decades, with the share of the labor force with a secondary education or higher increasing from 37 percent in 1982 to 58 percent in 2012 (World Bank).

In a 2013 report on the Malay education system, the World Bank reported on access within the school system, stating that, “the education system is fairly equitable, especially with respect to access to basic education. Relatively small gaps are observed along ethnic, income, gender or geographic lines with respect to access to pre-primary, primary and lower secondary education. Nevertheless, students from higher socio-economic backgrounds form a disproportionate share of those enrolling in post-secondary education.”

There are a number of different school types at the primary level, including national schools, ethnic schools (Chinese & Tamil most commonly), private schools and international schools.

Primary schools, regardless of institution type, follow the Malaysian National Curriculum. The curriculum includes study of a first language (Bahasa Melayu, Chinese or Tamil), English as a second language, Islamic education (compulsory for Muslims), mathematics, science, civics/moral education, local studies, physical education, health education, music and visual arts.

At the end of primary school, students take the Ujian Pencapaian Sekolah Rendah (Primary School Achievement Test) which rates achievement in written and spoken Malay and English, mathematics, and science concepts. All students automatically progress to secondary school.

Lower Secondary

The three years of instruction at the lower-secondary level (Forms 1 – 3) are not compulsory; however enrollment is close to universal with a 98.8 percent gross enrollment rate (lower secondary enrollment of any age as a percentage of total lower-secondary age population) and 96.4 percent net enrollment rate (enrollment among lower-secondary-age children as a percentage of total lower-secondary-age population).

Students attend national secondary schools with instruction in the national language (Bahasa Melayu). Students from Chinese or Tamil national-type primary schools do a transitional year before beginning lower secondary schooling. This year is called the ‘Remove Class’ and involves intensive language studies to prepare them for studies in the national language.

Students study a minimum of eight subjects. Core compulsory subjects include Bahasa Melayu, English, science, history, geography and mathematics. Elective subjects include Islamic studies, moral education, life skills, European languages and mother tongue.

At the end of the lower secondary cycle, students take the Penitaian Menengah Rendah (PMR, Lower Secondary Assessment). Students take tests in seven to nine subjects, including Bahasa Melayu, English, history, geography, mathematics and science. Students must pass the examinations to continue on to upper secondary school, and may be streamed according to their results.

Upper Secondary

Forms 4 and 5 make up the upper secondary level, and students typically attend one of three types of school:

- Academic (arts or science stream)

- Technical and Vocational (technical, vocational or skills training stream)

- Religious

Students are streamed according to choice and results on the lower-secondary leaving examination. They are required to take four core subjects regardless of streaming: Bahasa Melayu, English, mathematics, Islamic studies or moral education and history.

Students in the academic science stream must take: chemistry, biology, physics, additional mathematics and English for science and technology. Those in the arts stream take integrated science and a range of other non-science subjects as electives. Students can take no more than 13 total subjects.

In the technical and vocational streams, students generally take courses geared towards employment and trades at technical secondary schools. Fields offered in the technical stream include: mechanical engineering, civil engineering, electrical engineering, agriculture, commerce, food management and fashion studies. In the vocational stream, students can choose from: electrics, automotive, catering, computer programming.

Students in the technical and vocational streams can also prepare for the Sijil Kemahiran Malaysia (SKM – Malaysian Skills Certificate). The SKM does not lead to entry into programs in higher education; however, there is a five-level Skills Qualification Framework that certifies tradesmen up to the management level (SKM Level 5), which is considered comparable to degree level.

The Department of Skills Development [7] establishes the criteria for approval of Accredited Centers offering SKM programs and ensures that Accredited Centers offer, administer and maintain the quality of Malaysian Skill Certificates for specific jobs covered by the National Occupational Skills Standards.

At the end of the upper secondary cycle (Form 5), students from all streams take the Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (SPM – Open Certification Examination), which is administered by the Malaysian Examination Syndicate. The minimum condition for awarding the certificate is a ‘pass’ in the national language.

Students who are awarded the SPM can go on to pre-university or matriculation studies, or they can enter private colleges or universities for pre-university programs to advance to Bachelor Degree studies or other programs of their choice.

Chinese Secondary Schools

Students from Chinese-language primary schools can also enroll in Chinese secondary schools, which provide a parallel track to national schools (with an additional year of upper secondary) through the Malaysian Independent Chinese Secondary School system. Instruction is offered in Mandarin and follows the national curriculum.

The Junior Middle Examination is taken at the end of junior middle school (year 3). The United Examination Certificate for Independent Chinese Secondary Schools (UEC) is taken at the end of senior middle school (year 6).

The UEC can only be used for entry into private tertiary institutions. Students looking to enter public institutions must take the SPM, held in the Bahasa Melayu language. For this reason, many students from Chinese-medium schools choose to continue their studies in China or other overseas higher education institutions.

Senior Secondary

Pre-university

Entry to pre-university studies is based on the results of the SPM. Also known as Sixth Form, this cycle lasts two years and is divided into Lower Sixth Form and Upper Sixth Form. It is offered at national secondary schools, technical secondary schools, pre-university or sixth form colleges, Islamic schools, and some universities.

Students enter one of two streams: humanities or science. They typically take a general studies course and three other subjects.

At the end of the Sixth-Form cycle, students sit for the Sijil Tinggi Pelajaran Malaysia (STPM – Malaysian Higher School Certificate Examination), administered by the Malaysian Examinations Council. Students who pass at least one subject are awarded a certificate with subjects and grades recorded on it.

Students who attend Islamic schools for pre-university studies are awarded the Sijil Tinggi Agama Malaysia (Malaysian Higher Religious Certificate).

Matriculation

The matriculation cycle is just one year in length (two semesters) and designed to prepare well-qualified upper secondary graduates, as gauged by performance in the SPM, for entry into top-ranked universities. Students are streamed into Science, Accountancy and Technical streams.

And compulsory instruction is offered at Matriculation Colleges and MARA Colleges only. The curriculum is uniform and dictated by the Ministry of Education. Core subjects include: mathematics, chemistry, physics, biology and computer science (science stream); mathematics, accounting, business management and economics (accountancy stream); and mathematics, engineering chemistry, engineering physics and engineering studies (technical stream).

Additional compulsory subjects for all students include: English, Islamic studies or moral studies, Malaysian studies, communication skills and information technology.

Examinations delivered by the Ministry are taken at the end of each semester. The final examination is known as the Matrikulasi (Matriculation), and final results will also include scores from in-class assessment.

Higher Education

Under the ‘Vision 2020’ initiative set by the government, Malaysia seeks to become a high-income nation by 2020. One of the means of achieving this goal is education and the development of quality graduates, with a net tertiary enrollment ratio of 40 percent.

In recent years Malaysia has been focusing heavily on developing the research quality and quantity of its major universities, and the country currently spends 1 percent of GDP on research and development. Five of the country’s 65 universities and university colleges have thus far been granted ‘research university’ status, which means additional government funding and increased autonomy. The five research universities are:

- Universiti Malaya

- Universiti Putra Malaysia

- Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

- Universiti Sains Malaysia

- Universiti Teknologi Malaysia

According to statistics from Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM), the number of PhD students in Malaysia has increased from about 4,000 in 2002 to almost 40,000 in 2012. About half of these students are attached to the five research universities.

Malaysian Qualifications Framework

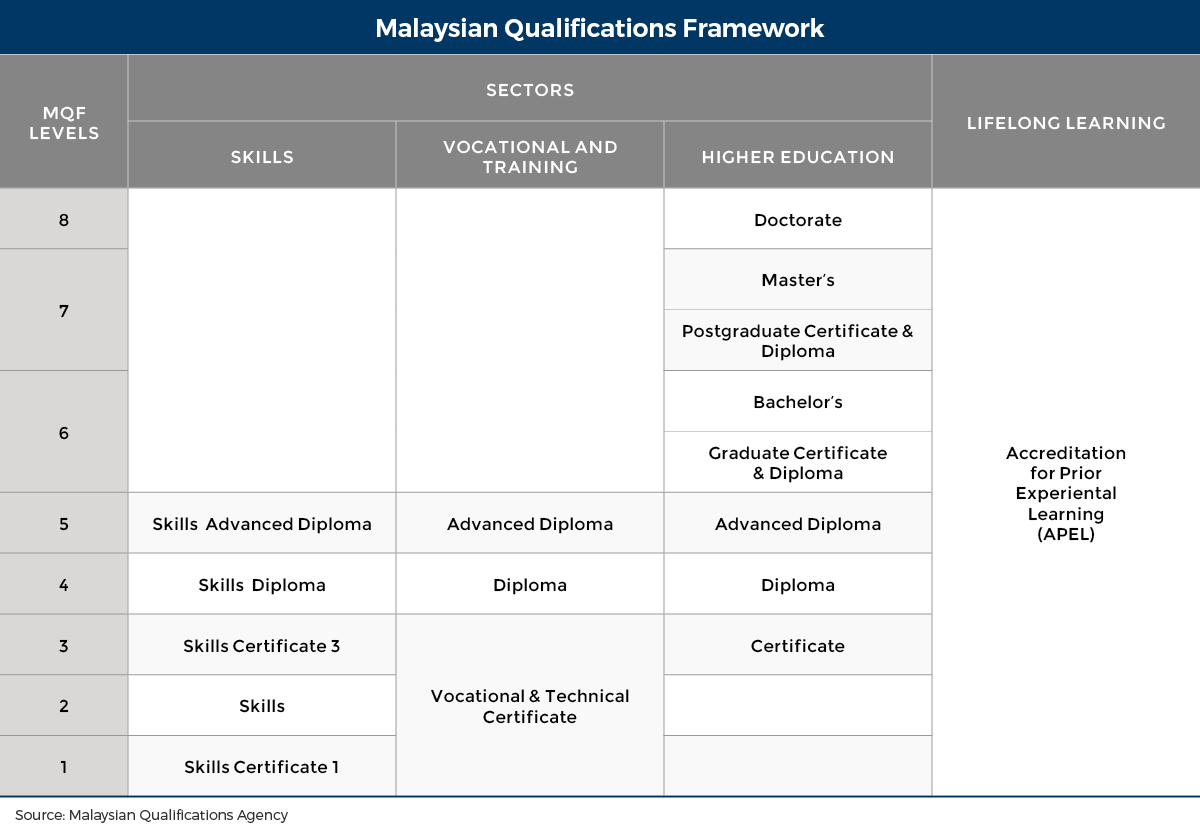

The Malaysian Qualifications Framework (MQF – Kerangka Kelayakan Malaysia) is a unified system of postsecondary qualifications offered on a national basis by both public and private institutions of education and also professional organizations.

It was introduced in 2007 and is administered by the Malaysian Qualifications Agency [8] (MQA), a statutory body under the Ministry of Higher Education [9] (MOHE).

The framework divides all qualifications into three sectors (skills, vocational and training, higher education), correlating with the type of institution offering the programs and expected outcome for holders of the qualifications.

The interconnected structure of the framework is based on nationally agreed-to criteria and benchmarking for naming and linking all qualifications. The benchmarks and framework levels are based on competency standards or learning outcomes in three areas: level of qualification, field of study, and program.

Accreditation

The National Accreditation Board (LAN – Lembaga Akreditasi Negara) was established in 1996 to oversee standards and the accreditation of academic programs at private colleges and universities in Malaysia. In April 2002, the Quality Assurance Division (QAD) was established by the Ministry of Education to oversee quality standards in public universities. Prior to the establishment of these bodies, no specific accreditation system existed.

With the adoption of the MQF in 2007 (see above) the QAD and LAN were merged to form the Malaysian Qualifications Agency (MQA). The MQA develops standards and criteria as national references for the conferral of awards, assures quality standards at higher education institutions and programs, accredits programs of study, and maintains the MQF.

The Malaysian Qualifications Register (MQR) provides information on all accredited programs, qualifications and higher education institutions accredited under the MQA. It acts as a reference for credit transfer from one accredited program to another. The MQA has responsibility for establishing and maintaining the MQR.

The MQA also operates a rating system, known as Discipline-Based Rating System (D-SETARA), that assesses the quality of teaching and programs of study at the undergraduate level in Malaysian universities and university colleges. It also has an institutional rating system known as SETARA, which is released every two years. Institutions and programs are rated on a five-tier scale. The process is voluntary.

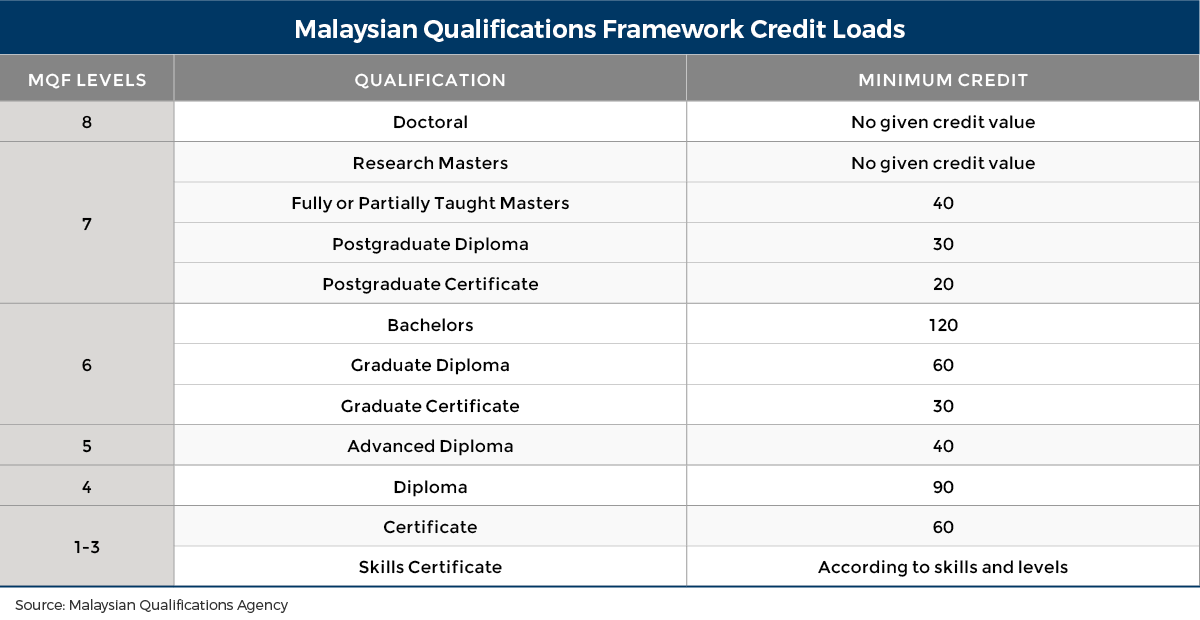

Credits

The MQA also operates a credit system which it uses to help provide uniformity and to aid in comparisons of qualifications within Malaysia and with overseas providers. The system allows 40 hours of academic load for each credit.

Academic load includes all learning activities undertaken to achieve a defined set of learning outcomes. Learning outcomes are linked to the credit system, which gives value to all students’ learning time not just on the contact hours between lecturers and students.

Institution Types

Private Colleges. Private colleges that do not have partnership agreements with Malaysian or foreign universities offer sub-degree qualifications. Those that do have partnership agreements with domestic or foreign universities can offer teaching programs leading to undergraduate degrees conferred by the partnering university. These programs are offered through twinning and franchise agreements typically, although other credit transfer and advanced standing programs also exist.

Under a franchise agreement, a Malaysian college teaches the courses of a foreign university entirely on its campus. These are known as 3+0 or 4+0 degree programs and are largely offered in business and accounting. All are taught in English. A twinning arrangement includes a year or two at the Malaysian college followed by another year or two at the foreign university. These are known as 1+2, 2+1 or 2+2 programs.

Community Colleges. Community colleges provide professional training through a variety of formal and non-formal courses and programs. They have been in existence in Malaysia since 2003. Formal programs lead to the award of Diplomas and Certificates, with a mix of practical (75 percent) and theoretical (25 percent) instruction. Oversight is through the Community College Department [12]. A government list of Malaysia’s 97 public community colleges is available here [13].

Polytechnics. Polytechnics offer programs leading to the award of Diplomas and Advanced Diplomas, with instruction including periods of work placement. Although these are considered comparable on the MQF to community college awards, entry standards are typically higher for polytechnics than they are for community colleges. Polytechnics are supervised by the Department of Polytechnic Education and the Department of Higher Education.

University Colleges. University colleges award their own Bachelor’s Degrees and Diplomas. They are smaller than universities, and typically offer a limited number of programs in specialist fields.

Universities. Public universities offer the full range of academic degrees from Diploma to Doctorate. The government maintains close control over the sector, although there are plans to increase university autonomy in the coming years under the 2013 Education Blueprint reform process.

Five universities have been designated research universities, a title that comes with increased autonomy and funding to undertake research collaboration with industry and foreign universities (see list above). There are two other types of public universities: Focused Universities (technical, education, management and defense), which enroll equal numbers at the undergraduate and graduate levels, and Comprehensive Universities, which enroll larger numbers of undergraduates and offer a broad range of programs.

The Private Higher Education Institutions Act 1996 allowed for the establishment of private universities, branch campuses of foreign universities as well as for the upgrading of existing private colleges to universities. The sector is regulated by the Private Education Department within the Ministry of Education.

There are currently 21 public (5 research, 5 comprehensive and 11 focused) and 44 private universities, including 9 international branch campuses.

Structure and Qualifications

Professional Education

Vocationally oriented Certificate and Diploma programs are offered at polytechnics, private colleges and community colleges.

Diploma programs take at least two years, usually three, and must include a minimum of 90 credits. Diplomas grant entry to further study leading to an Advanced Diploma or Bachelor’s Degree.

Certificate programs typically require two years of study and the completion of 60 credits.

Higher Education

At the sub-university level, polytechnics, private colleges, community colleges and some universities offer programs in professional fields leading to the following credentials:

Certificates require 1.5 to two years of full-time study (60 credits) following the Certificate of Education (SPM).

Diplomas require at least two years of full-time study, but typically three years of study (90 credits). Programs include both theoretical and practical studies and are focused in professional disciplines. Some Diploma programs provide advanced standing or transfer credit into Bachelor Degree programs. Entry is based on the Certificate of Education (SPM).

Advanced Diplomas require an additional 40 credits after a Diploma and are designed for managerial training in a professional context.

Bachelor’s Degrees require at least three years of full-time study and 120 credits. Degrees in professional fields require a higher number of credits and a longer period of study. Programs in accounting, dentistry, engineering, and law require four years. Programs in architecture, veterinary medicine, and medicine require five years of study.

Programs are generally structured with a year of generalist courses and core courses in the general field of study, with the remainder focused on compulsory core courses and elective courses in the area of specialization.

Private colleges offer various programs leading to Bachelor Degrees through special teaching and transfer arrangements with partnering domestic and foreign universities that typically award the degree.

Graduate Certificates and Diplomas. Considered equivalent in level to a Bachelor’s Degree on the MQF, Graduate Certificates require at least 30 credits and Graduate Diplomas require at least 60 credits. The qualifications are awarded following completion of education or formal training, recognition of work experience, inclusive of voluntary work or in combination. They are used for continuing professional development, changing a field of training or expertise, and as an entry qualification to a higher level with credit transfer.

Master’s Degrees. Master’s programs last one to two years following the completion of a Bachelor’s Degree. Programs can be undertaken as a pure research degree, pure coursework and examination or a mix of coursework and minor thesis.

Doctoral Degrees. Doctoral degrees are offered mainly at public universities although some private universities offer a limited number of programs, typically in applied disciplines and in collaboration with industry.

Admission Standards

Entry to three-year Diplomas is based on the Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (Malaysian Certificate of Education). Conferral of the Diploma can lead to advanced entry to some Bachelor Degree programs.

Entry to Bachelor Degree programs typically requires at least a Grade C (2.00) in General Studies and two other subjects on the Malaysian Higher School Certificate (STPM). Students must also have a pass in Bahasa Melayu in the Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (SPM) and a Malaysian University English Test Band Level 1.

At public universities, an Honors Degree with a high level of academic achievement is required for admission to Master’s programs. At private universities, a Bachelor Degree or equivalent, such as a professional qualification considered to be at Bachelor Degree level, is required.

A Master Degree is usually required for entry to doctoral programs.

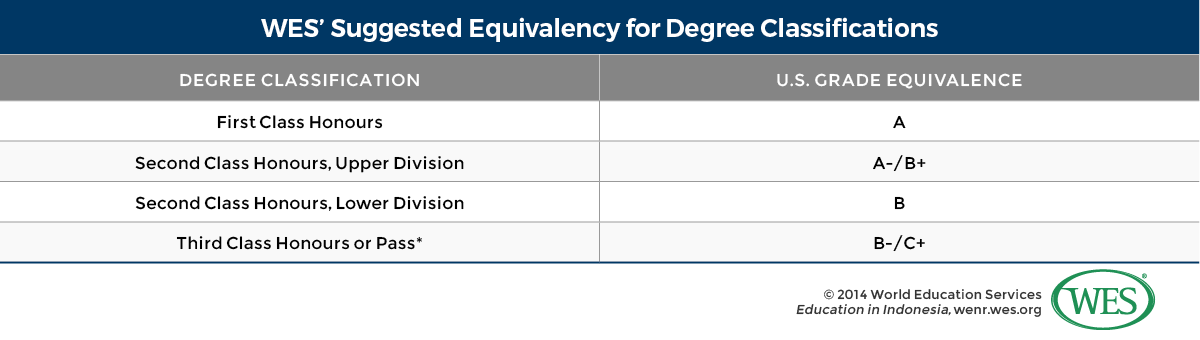

Grading Scales

There is some variation in the grading systems used for individual subjects. Many universities use a 4-point grading system for individual subjects and the cumulative grade point average (CGPA). Others use percentage grades. The following is WES’ suggested equivalency for degree classifications:

WES Document Requirements

For the evaluation of secondary documents, WES requires that all examination results be sent directly by the appropriate examining body. If the applicant has completed one or more years of postsecondary study, then they do not need to submit any secondary school documents with their applications.

For the evaluation of postsecondary credentials, WES requires the applicant to submit clear, legible photocopies of all degree certificates and diplomas issued by the institution attended. Academic transcripts for all postsecondary programs of study should be sent directly from the institutions attended. For completed doctoral programs, a letter confirming the awarding of the doctorate should be sent directly by the institutions attended.

For vocational and technical credentials, WES requires the applicant to submit clear, legible photocopies of all registration certificates/diplomas. Academic transcripts for all postsecondary programs of study should be sent directly from the institutions attended.

[15]Sample Documents

[15]Sample Documents

This file [15] of Sample Documents (pdf) shows a set of annotated credentials from the Malaysian education system.

- High School Examination Results (with translation)

- High School Examination Results (with translation)

- Diploma in Fashion and Retail Design

- Bachelor Degree Transcript

- Bachelor Degree Certificate

- Master Degree Transcript

- Master Degree Certificate

- Doctorate Degree Transcript

- Doctorate Degree Certificate

- Master Degree Certificate