Vijaya Khandavilli, India-U.S. Independent Education Consultant, and Nick Clark, Editor, World Education News & Reviews

Indian universities and state boards of higher education across India are in the process of implementing academic and structural reforms designed to improve student choice, academic mobility, and quality standards in Indian higher education under a federal and state government funding initiative known as Rashtriya Uchchatar Shiksha Abhiyan (RUSA).

An earlier WENR article [2] discussed in detail the academic reforms required by the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) under the RUSA reform initiatives. These include:

- Introduction of a semester system

- Introduction of the Choice-Based Credit System (CBCS)

- New assessment and grading systems

- Curricular updates and revisions focused on student learning outcomes

- New admissions procedures

This article will focus on the current state of implementation of these initiatives, with a particular focus on aspects of the reforms that directly impact the work of foreign credential evaluators, including the introduction of a credit-based semester system and new grading scales tied to cumulative grade point averages. The new semester-based evaluation system represents a significant departure from India’s traditional year-end system of assessment, and is designed to give students more choice and reduce the burden of annual examinations.

Devolving federal funding and oversight of higher education to the states

According to the RUSA planning documents [3], the existing funding model for Indian universities and colleges through the University Grants Commission (UGC) excludes from federal funding approximately one third of state universities and half of colleges affiliated to state universities.

The RUSA scheme is designed to decentralize funding and oversight of state public education through the distribution of federal funding to those state universities and colleges that do not currently receive it. Autonomous State Higher Education Councils (SHEC) are to be the centerpiece of this devolution, taking over responsibility for the distribution of state and federal funding, while also developing state-wide quality assurance processes and institutions.

The intent is that implementation of RUSA reforms will be managed by the SHECs in order to:

“Attain higher levels of access, equity and excellence in the state of higher education systems with greater efficiency, transparency, accountability and responsiveness.”

To promote accountability and implementation, the initial distribution of RUSA funding is tied to a list of 16 requirements that states and state universities must meet. Further funding distributions will be tied to specific performance indicators related to governance, academic excellence, equity, research and innovation, student facilities and infrastructure. The initial list of requirements includes:

- The creation of new universities through the upgrade of existing autonomous institutes of excellence

- Reforms to the affiliating system

- The creation of state accreditation agencies

- The expansion of academic programs and disciplines

- The implementation of academic, assessment and grading reforms

These reform initiatives were initially outlined in India’s 12th Five-Year Plan [4] (2012-2017) and are based on reforms introduced in 2008 at a number of federally funded central universities. By March 2009, many central universities had begun the process of introducing new structures including the two-semester academic year and a new grading system for select graduate programs and academic departments. The RUSA initiative for state universities was launched in 2013 and – given the scope of the reforms – will run through the current and next planning periods to 2022. Of India’s 29 states and seven union territories, currently 27 are engaged [5] in the RUSA scheme, six more have shown a willingness to participate, and just three are not yet committed in any way.

State Higher Education Councils (SHECs) to lead reform implementation

The National Policy on Education [6] (NPE), 1986, originally recommended the creation of SHECs as intermediary bodies for better planning, coordination, capacity building and oversight, in recognition of the fact that the Indian system of higher education is too big for a central coordinating body such as the UGC. One of the prerequisites of the RUSA scheme is that individual states form an SHEC to implement the central initiatives of the scheme so that they can be coordinated in tandem with state-level needs.

Eight states created SHECs in the years after 1986. These were: Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Gujarat (through the Gujarat Knowledge Consortia). According to the Ministry of Human Resources Development’s 2014 Status of Higher Education Report [5], a total of 17 states had received preparatory RUSA grants as of August 2014, while 18 had submitted State Higher Education Plans.

Given the important role envisioned for the SHECs and the linking of federal funding to their creation, it is expected that all those states that currently do not have functioning SHECs will soon form them. However, a recent report [7] from the World Bank on the effectiveness of the eight original SHECs suggests that much needs to be done for them to meet the objectives envisioned by RUSA.

“As a general observation, the case studies reveal a significant gap between the formal (de jure) state legal provisions related to SHECs’ functions and the actual implementation (de facto) of these provisions.”

Assessing reform implementation

The primary objective of this research is to understand how grading scales, divisional classifications, and assessment mechanisms are changing at institutions of higher education across India; if there is grading consistency across institutions; and how program structures have been altered with the introduction of the student-centered Choice Based Credit System.

To understand how academic reforms are being implemented, we examined progress at 34 colleges and universities from 14 different states and jurisdictions across India, looking at institutional websites and interviewing faculty and administrators. The institution types include central, state (public and private), deemed universities, universities with potential for excellence, and autonomous colleges and universities.

In addition, we offer examples of academic documents with new grading scales and grade point averages that WES has begun to receive over the last couple of years.

Semesters, credits and grading schemes

In a 2009 communication to university vice chancellors outlining desired reforms, the chairman of the University Grants Commission expressed the need to “move away from [the] marks and division system in evaluation and [the] need to introduce [a] grading system – preferably on a 9-point scale.” His recommendation on introducing grade points was that it should be “based on a 5-point or 10-point scale and it could vary from institution to institution.”

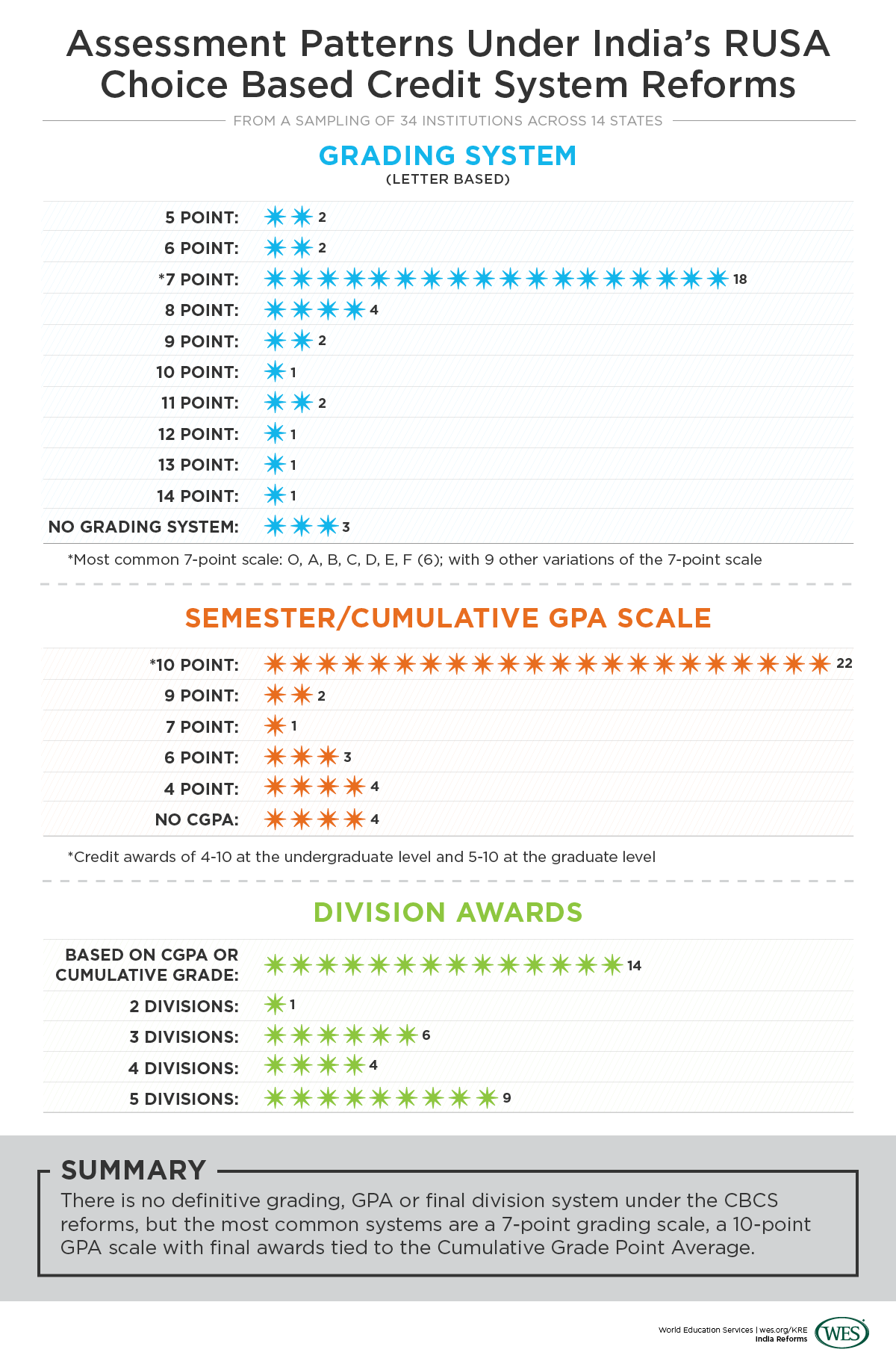

The RUSA scheme also encourages the introduction of a new Cumulative Grade Point Average (CGPA) to replace – or supplement – final award divisions. To date, 29 of the 34 institutions we surveyed have adopted a version of the new grade-point system at least at one academic level. The 10-point scale appears to be the most common, although it is far from universal.

All institutions have replaced the traditional term system with the new two-semester system, while a total of 25 have introduced the semester system, the CBCS credit system and a new grading system. A total of 18 institutions are using a 7-point grading scale (in place of traditional percentage marking), while the rest are using anything from a 5-point scale up to a 14-point scale. Additionally, some institutions have adopted different grading scales for undergraduate and graduate programs or for different academic departments. There is also significant variation in mark-to-grade-point equivalencies, where institutions still report marks on their transcripts.

The most common 7-point scale – used by six of the institutions surveyed – runs from a high grade of O (outstanding) to a low of F (fail), with traditional A through E divisions between. However, there appears to be great variation in naming and lettering protocol between institutions. Where grade points have been introduced, the equivalency of grades to grade points most commonly runs from 10.0 for top grades to 4.0 or 5.0 for the lowest passing grades.

Grading scale examples and sample documents

At the University of Mumbai, a large state university in Maharashtra, a new 7-point grading scale was introduced in 2011. This grading scale is the most common we have seen; however, the 7.0 grade point system is relatively uncommon. Also of note is the traditionally low marking equivalency, with a performance of 70 percent and above required for the top grade. At other universities, we are seeing much higher mark/percentage thresholds for top grades.

For each course, the grade card – or transcript – shows: marks, credits earned, grade, grade (quality) points and sum of quality points x credit weighting. For each semester, a semester grade point average (SGPA) is recorded, which is averaged out over the course of a program as a CGPA. The final degree award is expressed as a grade (as corresponds to the CGPA per the table below) as opposed to traditional divisional awards.

In the sample Master of Science documents shown here, the student has a CGPA of 6.29 over 96 earned credits, which equates to an overall grade of ‘A’.

[10] Sample Documents: University of Mumbai

[10] Sample Documents: University of Mumbai

[11]

[11]

Presidency University, formerly a constituent college of Calcutta University was awarded university status in 2010. It uses a different 7-point grading scale from Mumbai, with equivalent grade points running from 5 to 10, which is more common than Mumbai’s 1-7 scale. Also of note are the high marks required for top grades at Presidency University and the 10-mark spreads between grades. This is a significant change from traditional, more stringent marking schemes common to older Indian universities such as Mumbai, which uses 5-mark spreads between grade thresholds, bringing up questions related to grade inflation.

At St. Xavier’s College, an autonomous college under the University of Mumbai system, a 9-point grading scale and 4.0 grade point system is employed for its Bachelor of Science degrees. Although St. Xavier’s uses 5-mark spreads for individual grades, the additional grades in the 9-point scale mean that the top A++ grade requires marks of 85 or higher, versus 70 at Mumbai, the parent university (see above). The passing standard of 40 percent is the same as at Mumbai.

The final degree certificate expresses the CGPA, 3.58 over 146 credits in the example shown below, and the corresponding overall class award, ‘Distinction’ in this case.

[14] Sample Documents: St. Xavier’s College

[14] Sample Documents: St. Xavier’s College

Wide variety in final division classifications

For final division classifications, there appears to be a wide range of scales, from two to six divisions among the institutions we sampled. For example, Madurai Kamaraj University, a state university with potential for excellence in Tamil Nadu, awards just two divisions at the master’s level: First Class (6.0 to 10.0 CGPA) and Second Class (5.0 to 5.99 CGPA), but also awards 10 final grades in .5 CGPA increments. Final awards show both the division and the CGPA.

Meanwhile, Gujarat University, Osmania University, the University of Hyderabad [15] (except M.Phil and M.Tech programs, which use three divisions), and the University of Madras award as many as five final divisions. Six of the institutions sampled continue to award the traditional three divisions.

Many of the institutions offering additional division awards now have different levels of the First Class division (Outstanding, Exemplary, and Distinction are common examples), Second Class division, and often a Pass division. Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha (GGSIP) University, New Delhi, uses a five-division final award scheme [16], with three separate First Class awards. The divisions are linked to cumulative marks, which the university terms its Credit Point Index (CPI). Students must complete a minimum of 150 credits for the award of bachelor degrees.

In the sample document below from GGSIP University, the student earned 160 credits (of which 152 counted towards the CPI), and achieved a final CPI of 71.32, which equates to a final degree division of First Class.

[18] Sample Documents: Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University

[18] Sample Documents: Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University

In the St. Xavier’s College example above, four final divisions are awarded: Distinction, First Class, Second Class, and Pass. The final divisional award in the example shown is tied to the student’s CGPA, which is expressed on the final degree certificate alongside the divisional award.

The University of Mumbai classifies final degrees according to its grading scale and overall GPA. In the sample document provided above, the student graduated with a CGPA of 6.38 which equates to an overall grade of ‘A’.

The University of Madras uses a modified version of the traditional three division scale, tied to the CGPA, with slight variations between undergraduate and graduate degrees. For individual courses, the university employs an 8-point grading scale at the undergraduate level (O, D+, D, A+, A, B, C, U) and a 7-point scale at the graduate level (no ‘C’ grade), both tied to a 10.0 grade point scale. For final awards, the university doubles the number of grades (12 passing grades versus 6 for individual courses) to allow for half credit point intervals between 4 and 10. There are four degree classifications at the graduate level and five at the undergraduate level. Like GGSIP University, it awards three different types of First Class award.

In the Madras sample document below, the Master of Commerce student has an overall grade point average of 7.654 (Grade D) for the 91 credits completed, which equates to an overall degree classification of First Class with Distinction.

[20] Sample Documents: University of Madras

[20] Sample Documents: University of Madras

Assessment

With the intention of lessening the burden of end-of-semester/year examinations, the RUSA reforms require that students be assessed both during the semester and at the end of the semester.

The weighting of Internal Assessment and End of Semester Examinations in course evaluations typically range from 20:80 to 50:50 for theory-based courses, the former being the most common. For practical courses, ratios range from 40:60 (most common) to 60:40. Typically, affiliated colleges are responsible for internal assessment while the parent university grades end-of-semester examinations.

The overall pass mark in most universities at the undergraduate level is 40 percent, with a range between 30 percent and 50 percent, the latter mostly for graduate programs. Pass percentages differ between programs and departments in some universities. In addition, individual courses may have a pass percentage threshold that is different from the required aggregate pass percentage for the full program.

Grade cards (or transcripts) also come in a variety of forms but a uniform grade card has been advised by the UGC to facilitate the mobility of students across institutions, a desired intent of the introduction of a common credit system under the RUSA reforms. It should typically list:

- Name of the university/college

- Name of the program

- Semester number

- Name and registration number of the student

- Code, title, credits and maximum marks for each course taken during the semester

- Internal, external and total marks awarded

- Grade, grade point and credit point allocation for each course taken

- The total credits, total marks (max. & awarded) and total semester credit points

- Semester grade point average (SGPA) and corresponding grade

- Cumulative grade point average (CGPA)

The final mark sheet or grade card issued at the end of the final semester should contain the details of all courses taken during the final semester and also include the final grade/marks scored by the candidate for all courses from the first to the final semester. The overall grade/marks, CGPA, and division for the entire program should also be included.

Credit and course requirements

Under the new semester-based credit system, students are required to accumulate a minimum number of credits in order to graduate. However, these credit requirements vary by institution.

Of the institutions we sampled, successful completion of undergraduate (non-technical) degrees ranged from 120 credits (Himachal Pradesh University, Jamia Millia University, Kannur University, Kerala University, the University of Calicut, and the University of Mumbai) to 135 credits at Guru Nanak Dev University, 140 at the University of Madras, 144 required by the Gujarat Higher Education Department for the award of honors degrees, and 156 credits at Gujarat University.

Credit requirements for four-year undergraduate technical degrees (B.Tech) ranged from 180 at Guru Nanak Dev University to 218 credits at GGSIP University. The five-year integrated master’s program at Guru Nanak Dev University requires successful completion of 225 credits.

At the master’s level, credit requirements for two-year programs ranged from 72 credits at central universities in Gujarat and Kerala to 105 credits for the award of the M.Sc. (biotech) at GGSIP University. The MBA degree at NC College of Engineering, under Kurukshetra University, requires the completion of 136 credits.

Gujarat University

Gujarat University, Ahmedabad, introduced the Choice Based Credit System and semester system across all disciplines and academic levels beginning in academic year 2011-12. At the undergraduate level, students take mainly core courses (3 CBCS each), in addition to one or two foundation or elective courses (2 CBCS each) per semester. Students must successfully complete 156 credits for B.A. awards and 150 credits for B.Sc., BBA or B.Com degrees.

Credit weighting for taught courses is based on weekly instruction time, so a class that meets for three hours each week would typically be a 3 CBCS course. Practical classes such as labs are weighted at 1.5 hours a week per credit.

Evaluation is conducted by continuous internal assessment (30 marks) and end-of-semester examination (70 marks). The pass threshold is 40 percent. Marks are converted to grades and grade points at the end of each semester, and students carry their Cumulative Grade Point Average (CGPA) through to graduation. The CGPA for all core courses is used to assess the final degree division. For foundation and elective courses, students must meet the minimum passing standard, but the grades in these courses do not affect the overall CGPA.

Per the guidelines issued by the Gujarat State Education Department, the University of Gujarat computes grades through a relative-grading normalization process.

Himachal Pradesh University (HPU), Himachal Pradesh

Himachal Pradesh University introduced its Regulations for CBCS and Continuous Assessment Grading Pattern [22] in 2013. The regulations are relevant to all 300 colleges affiliated to the university and effective for undergraduate programs from academic year 2013-2014.

Per the regulations, for a student to be awarded an undergraduate degree he or she has to successfully complete 120 credits in the prescribed ratio of core and elective courses in a minimum of three years (six semesters) and a maximum of five years (10 semesters). One hour of lectures or tutorials and two hours of practical classes per week are weighted at one credit over the course of a semester.

A student that accumulates 15 additional credits with a minimum of an ‘A’ grade can be considered for a bachelor’s with a ‘major with emphasis.’ Students with an additional 30 credits at a grade ‘A’ or better are awarded a ‘double major.’ All students must take a minimum of three and a maximum of six, 3-credit compulsory courses; 14, four-credit compulsory core courses (“hard core” courses being mandatory and “soft core” courses being chosen from a pool of offerings); and 10-13, four-credit elective courses (more for a ‘double major’). Students may also take up to nine credits in general interest/hobby courses.

Students who are unable to complete the full 120 credits required of an undergraduate program will be considered for the awards of: Certificate (48 credits, with 16 in core courses); Diploma (96 credits with 32 in core courses); B.A./B.Sc. Pass Degree (100 credits with 30 credits in each of three subjects).

Grading is based 50 percent on internal assessment and 50 percent on end-of semester evaluation. Where student numbers on a particular course (across all colleges) are 50 or less, grading is absolute. Where the number of students is more than 50, grading is relative.

Final degree classifications are categorized into five divisions, according to CGPA: First Class Exemplary (9.01 & above); First Class Distinction (7.51 – 9.0); First Class (6.01 – 7.5); Second Class (5.01 – 6.0); and Third Class (4.51 – 5.0). The CGPA earned by the student in core and elective courses will only be considered for division/class and gets reported on the certificate.

University of Madras, Madras

The University of Madras adopted the CBCS [24] at both the graduate level and the undergraduate level in the 2008-09 academic year. However, from the documentation WES has received, it appears that implementation at affiliated colleges varies, with autonomous colleges the most likely to have implemented all CBCS reforms. Implementation and oversight of CBCS structures and standards are conducted by a dedicated CBCS office within the university.

Under the university’s CBCS regulations, three-year undergraduate degrees are awarded upon successful completion of 140 credits. A 7-point letter grading system is used (see scale above), and the minimum pass mark for individual courses is 40 percent. For five-year integrated master’s programs, the passing minimum in the first three years is 40 percent and 50 percent in the 4th and 5th years. Three hours of lab work or practical training is generally considered equivalent to one hour of lectures.

For the award of two-year master’s degrees, a minimum of 88 credits (60 credits from core courses, 18 credits from electives, and 10 credits from soft skill courses and internships) must be accumulated. For the award of three-year master’s degrees, a minimum of 117 credits must be accumulated in core and elective classes (90 credits from core courses, 27 credits from electives), in addition to 15 credits from soft skill courses and internships. Assessment is based on in-term tests and performance (40%) and end of semester examinations (60%). The best 72 credits (54 core and 18 elective) count towards final divisional scores for two-year masters and the best 108 credits (81 and 27) for three-year masters.

University of Mumbai, Mumbai

The University of Mumbai instituted the CBCS reforms in 2011-12 with updated regulations introduced in 2012-13. According to the most recent regulations, courses are assessed on a ratio of 40:60 between internal assessment and end-of-semester exams. If a student is successful in either internal assessment or end of semester examinations but fails the other, the passing marks in one segment will be carried forward and upon passing the second segment, the final grade will be awarded on the basis of carried over marks.

Credit allocation at the University of Mumbai is based on a recommendation of one credit per 30-40 learning hours (in and out of class). At the undergraduate level, a minimum of 120 credits is required for the award of a bachelor degree. At the graduate level, students must earn a minimum of 96 credits.

The University of Mumbai’s grading scale can be viewed above.

Reform implementation is ongoing, grading equivalencies should be conducted on a case-by-case basis

The implementation of reforms to academic structures as required by the RUSA scheme is progressing at institutions across India. As of August 2014, a total of 17 states had received preparatory RUSA grants to put management, monitoring, evaluation, and research (MMER) systems in place.

The Ministry of Human Resource Development’s 2013 RUSA planning document placed a two-year implementation window on its mandated objectives at central universities and three years at state universities. In January 2015, the University Grants Commission urged those institutions that have not already adopted the semester-based credit system to do so by the start of the 2015-16 academic year, and according to a recent article [25] in The Times of India, state ministers of education have agreed to implement the new systems where progress has not already been made. As funding is now directly linked to the progress of reforms, it is expected that most universities and colleges will implement the reforms by academic year 2016-17 at the latest.

From our sampling of institutions, it would appear that some universities are implementing the new systems more proactively and innovatively than others. Movement is swifter in states where state higher education councils or state government education departments are active and have issued clear guidelines to institutions. The Tamil Nadu State Council for Higher Education and Gujarat Education Department are two such state bodies that are proactively encouraging implementation.

A case in point is the newly appointed and empowered committee [26] at Delhi University. Dr. Hemalata Reddy, Principal of SV College, Delhi University and a member of the planning committee is hopeful that academic and structural reforms at the university will be rolled out in academic year 2015-16. Though advisory in function, Reddy feels that his committee will be able to address the concerns of teachers and students to incorporate suitable suggestions in the final document that will be presented for ratification by the Academic Council and Executive Council of Delhi University. His hope is that with the introduction of a uniform grading and credit system, the mobility of students between colleges and institutions will become much easier. He is also hopeful that new credit transfer procedures will enable far greater opportunity for international academic exchanges with foreign universities.

However, from our research and from the documents that we have begun to receive for credential evaluation, there does not appear to be any one common grading or grade point system. Whether that will change in the coming years is yet to be seen, but for the current time, we recommend that equivalencies for new grading scales, grade point averages and divisional awards be established on an institution-by-institution basis.