By Nick Clark, Editor, World Education News & Reviews

Jump to: The pre-1992 Soviet education system [2] | 1992-2005: Post-Soviet System of Education in Central Asia [3] | Azerbaijan [4] | Kazakhstan [5] | Kyrgyzstan [6] | Tajikistan [7] | Uzbekistan [8] | Turkmenistan [9]

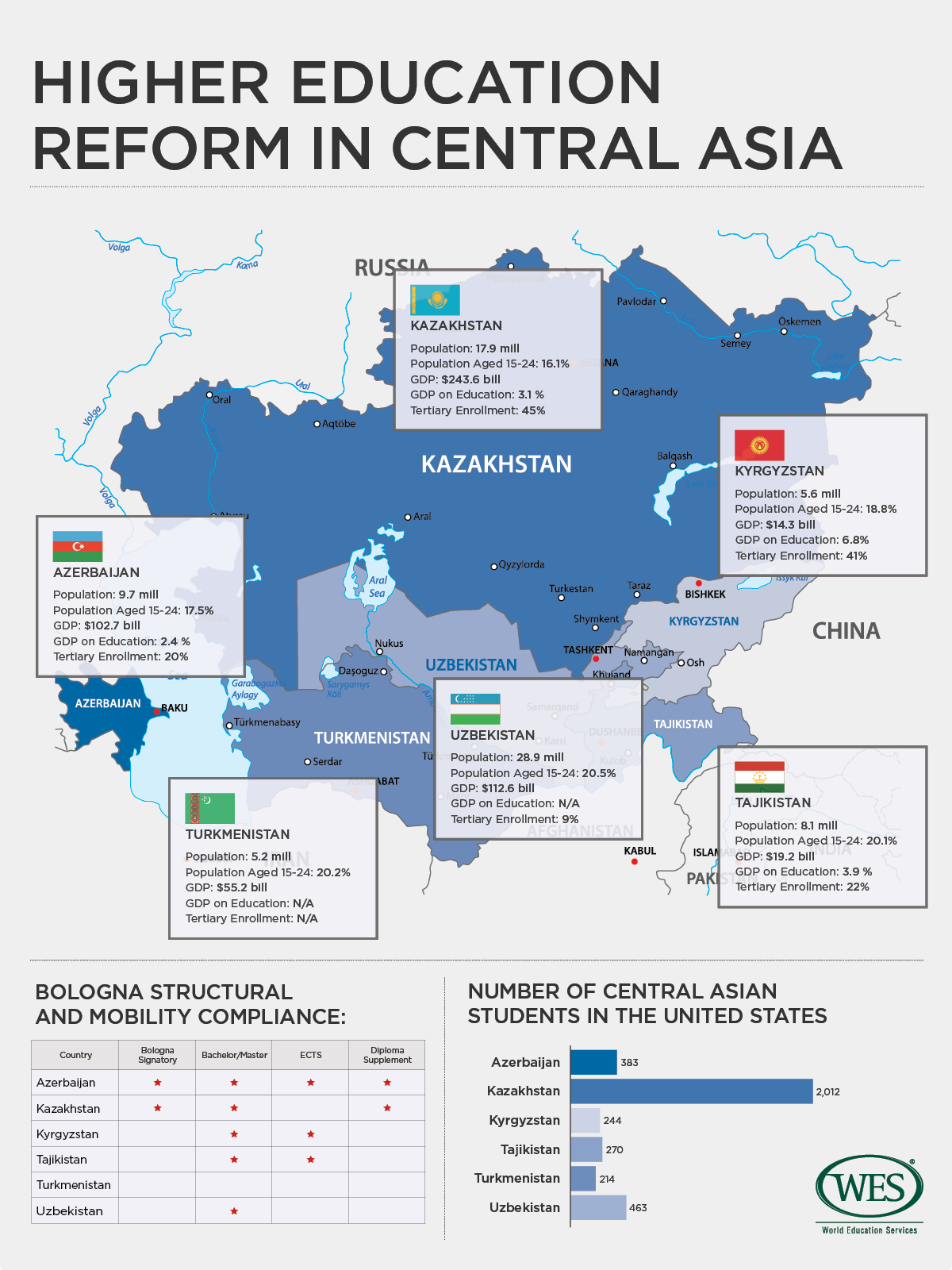

Later this month, 47 ministers responsible for higher education will meet in Yerevan, the capital of Armenia to discuss the future of the European higher education harmonization project, known commonly as the Bologna Process. The meeting location is significant because both politically and geographically the country is not considered a part of Europe. This draws attention to the fact that the influence – and indeed membership – of Bologna has grown to include many countries of the former Soviet Union, as far afield as Kazakhstan, a country of Central Asia that shares an 1,100-mile border with China and no physical connection to Europe.

Kazakhstan is one of five countries that make up the Central Asian region and it is the only one that is a formal member of the Bologna Accords. Nonetheless, both Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have made significant reforms to their higher education systems over the last decade that align them closely with the Bologna model. The other two countries of the region – Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan – still maintain Soviet-style systems, yet are involved in a nascent project to align their higher education systems under the proposed Central Asian Higher Education Area [10] (TuCAHEA) modeled on Bologna’s European Higher Education Area.

In this article, we look at the education systems of these five Central Asian countries, profiling changes that have been made (or not made) since the fall of the Soviet Union, and look at new academic credentials that are now being awarded. We also offer a look at Azerbaijan’s higher education system, an example of another former Soviet republic that is a member of the Bologna Process and has reformed its structures accordingly.

Bologna: Initially conceived of as a European higher education project

The Bologna Process [12] began over 15 years ago in 1999 and is considered by many as one of the most ambitious regional higher-education reform initiatives ever undertaken. From the outset, the goal of the project has been to encourage academic and workplace mobility across international borders through increased compatibility and comparability of higher education qualifications, programs, and course content.

To accomplish this, a two-degree structure of bachelor’s and master’s degrees was agreed upon, with doctoral degrees subsequently added to the shared academic architecture. And from this shared structure, subject curricula are being ‘tuned [13]’ across systems such that learning outcomes and student competencies within specific disciplines share common points of reference, convergence and understanding. The intended outcome of these structural and curricular reforms is that subject-specific credentials be broadly comparable at different levels within the European Higher Education Area (EHEA).

To encourage academic mobility and transferability, a number of ‘tools’ have been established which include – most notably – the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System [14] (ECTS). In tandem with these reforms, continental mobility programs such as Erasmus [15] have been greatly expanded to help students and faculty move across national borders. This has made the Bologna Process a vital piece of the European Union’s integration puzzle, both within its own borders and beyond to other regions around the world.

The former Soviet republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine are all now members of Bologna’s EHEA, and Belarus is being considered for a final round of expansion at the upcoming ministerial conference in Armenia. In addition, there are a number of other republics that have reformed their education structures to be compatible with those of the EHEA, typically with the support of the EU’s TEMPUS [16] (Trans European Cooperation Scheme for Higher Education) program.

In Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have both reformed their education structures in line with the EHEA model as a means of modernizing their higher education systems. In this general context, the European offer of non-invasive models and assistance in developing higher education has had notable success, and today the five republics of Central Asia have begun work on aligning learning competencies, curricula and assessment methods under the aforementioned TuCAHEA [10] initiative.

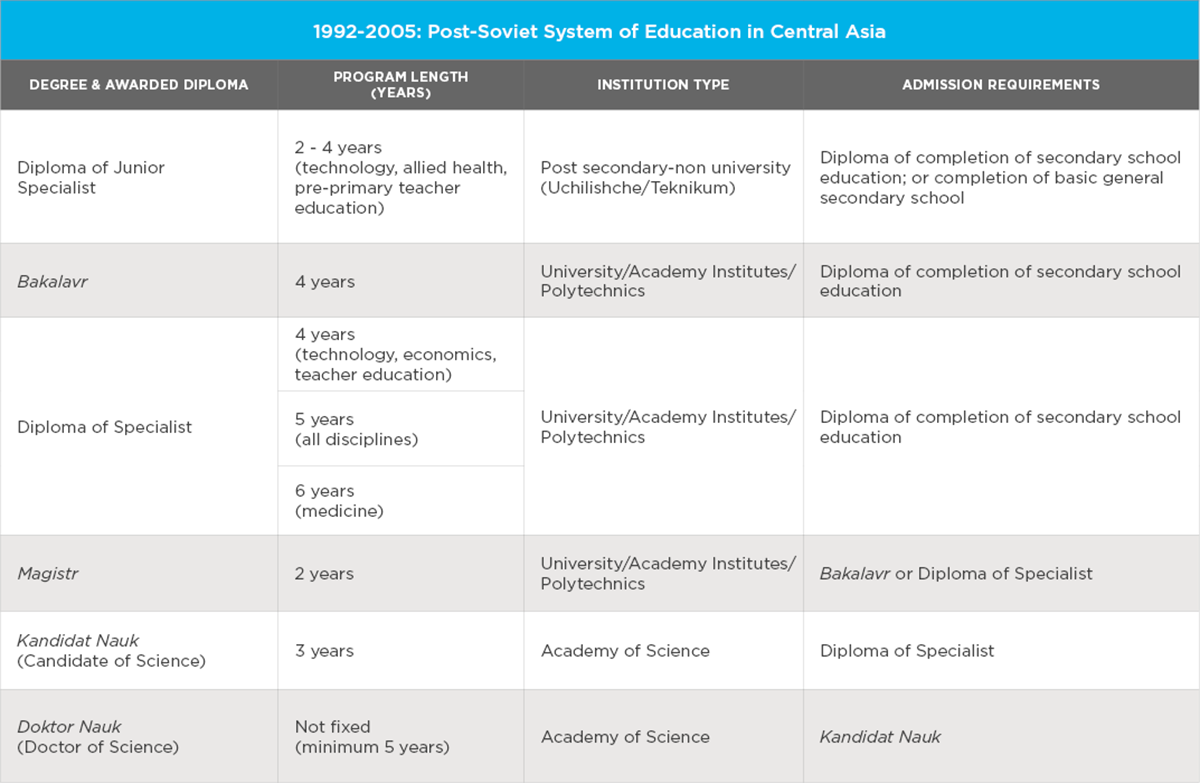

Academic Mobility to the United States from Central Asia and Azerbaijan

There is significant wealth disparity among the Central Asian countries. Kazakhstan, like Russia, is a hydrocarbon exporter and enjoys significant comparative wealth as a result. This goes a long way to explaining why well over half of the enrollments from the region in the United States are from this vast, but sparsely populated country. Turkmenistan also enjoys gas wealth, but an autocratic and staunchly anti-Western post-Soviet leadership has prevented most of its citizenry from traveling abroad for study, while the other Central Asian Republics are among the poorest of the former Soviet states in terms of per capita income, so international academic mobility from these countries tends to be towards more affordable and culturally familiar universities in Russia.

Parallel Systems of Higher Education: Bologna and the Soviet Union

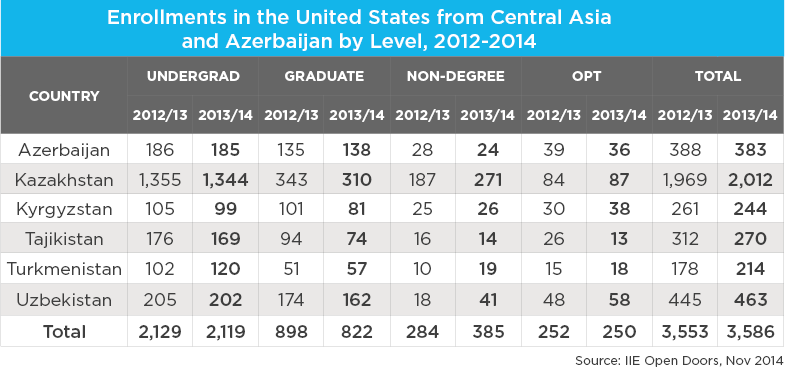

The pre-1992 Soviet education system

Prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, all of the republics of Central Asia followed the centralized Soviet system. The table below highlights the main credentials and awarding institutions of the Soviet system.

Notes

Diploma of Junior Specialist: the length of this program depended on the level of education with which the student entered. Those who had completed just the basic stage of the secondary cycle undertook four years of study with the first two years at the senior secondary level, while those with a secondary school diploma undertook two to three years of tertiary-level study.

Diploma of Specialist: this was the most common academic qualification under the Soviet higher education system and required four to six years of study depending on the subject area, as noted in the table.

Kandidat Nauk: study for the Kandidat Nauk was conducted at research institutes under the Academy of Science. Students enrolled in these programs were generally on track to become researchers or professors at the university level.

Doktor Nauk: there was no fixed program length for these programs, taking anywhere from five to 15 years. This was the highest award in the Soviet system.

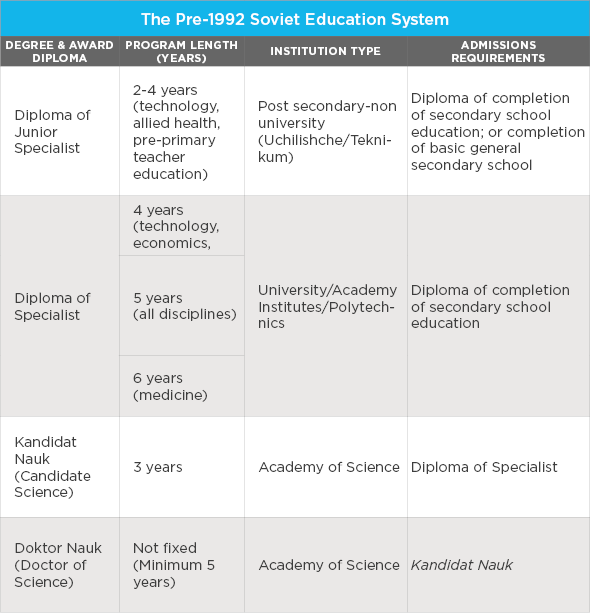

1992-2005: Post-Soviet System of Education in Central Asia

The collapse of the Soviet Union had a strong impact on the education systems of each of the six countries profiled below, most noticeably at the higher education level which was more fully integrated across the Union than primary and secondary education. Despite their common origin, each higher education system in Central Asia today is evolving its own national education context.

Notes

Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, institutions of higher education were just starting to offer two new qualifications modeled on the Anglo system of bachelor and master. In Russian nomenclature, these were the Bakalavr and Magistr. With the exception of these two new degrees, the credentials awarded under the higher education systems of the former Soviet republics remained essentially the same as they were prior to 1992, up until the introduction of reforms starting in the new millennium.

Current Higher Education Systems of Six Former Soviet Republics

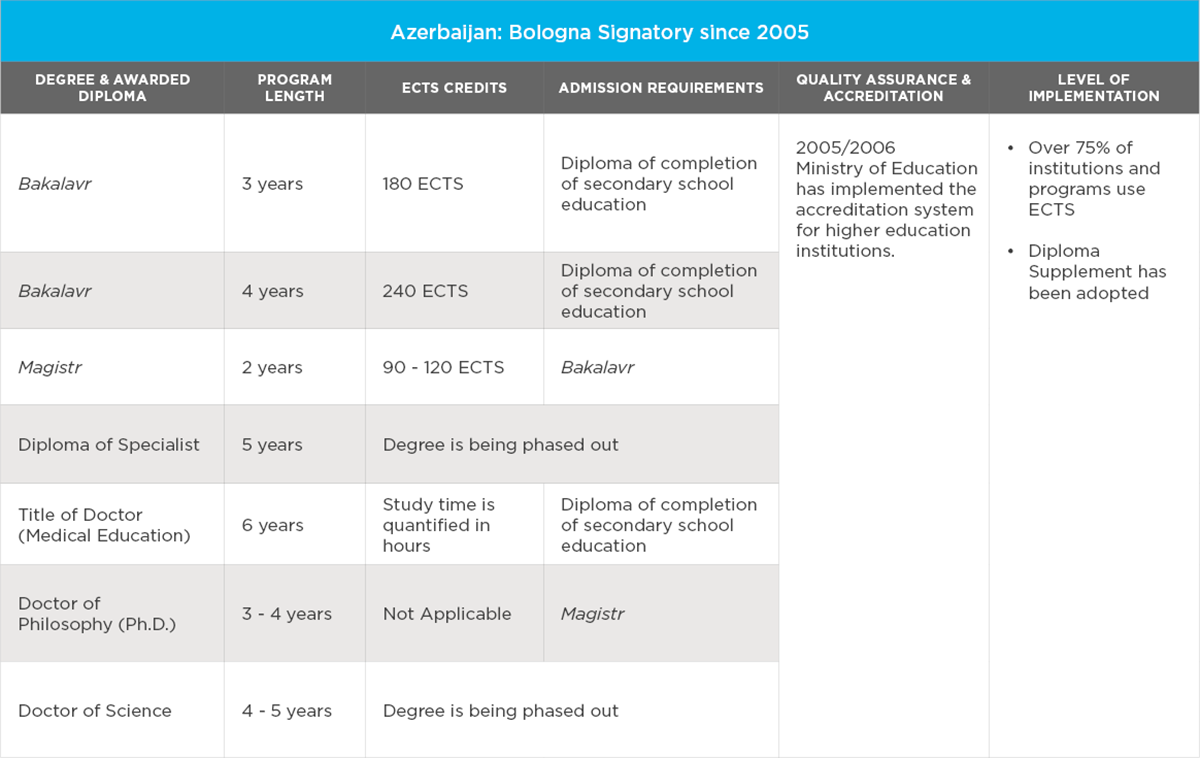

Azerbaijan: Bologna Signatory since 2005

Higher education reforms enacted in 1993 resulted in the establishment of a two-tier higher education system in Azerbaijan consisting of undergraduate education (bakalavr təhsil səviyyəsi) and graduate education (magistr təhsil səviyyəsi). Since then, further reforms have been undertaken, much of them inspired by the European model.

The first bachelor’s degrees were awarded in 1997, and since then a total of 32 higher education institutions (both public and private) have begun providing graduate education at the master’s, or magistr, level. With these structures already in place, and with the introduction of a credit system modeled on the European ECTS system, Azerbaijan applied for and became a signatory to the Bologna Accords in 2005. The degree structure in place today is broadly in compliance with the Bologna model, and the ECTS credit system is widely used at institutions of higher education across the country.

Qualifications

A new education law was adopted in June 2009 that introduced the three-cycle, Bologna compliant higher education system, comprising the following levels:

- Bachelor (Bakalavr): typically four years in duration, although approximately 20 percent of bachelor programs are three years in duration.

- Master (Magistr): typically two years in duration.

- Diploma of Specialist: this Soviet-hold-out degree is close to being fully phased out.

- Doctorate (Doktoru): Upon completion of doctoral studies, students are awarded the academic title of Doctor of Philosophy –Ph.D. (Fəlsəfə elmləri doktoru) or Doctor of Science – D.Sc. (Elmlər doktoru) specifying the relevant field of study. Like the Diploma of Specialist, the Doctor of Science is a remnant of the old system and is being phased out.

- Title of Doctor: medical education includes basic education courses and graduate studies. Upon completion of medical education, graduates are awarded the academic title of doctor.

[21]Sample Documents: Azerbaijan [21]

[21]Sample Documents: Azerbaijan [21]

Magistr Degree Certificate, Diploma Supplement and Transcripts

- This is a two-year Master of Business Administration degree issued by Khazar University, a private state-recognized institution established in 1991.

- The Diploma Supplement is compliant with the Bologna model and provides detailed information related to grading, program length, language of instruction (English), admission requirements, and program requirements.

- The transcript shows courses taken, grades achieved and ECTS credits awarded. This is a 90 ECTS program.

- The diploma supplement provides additional information related to the education system of Azerbaijan. It should be noted that the supplement is not always issued and sometimes has to be requested by the student. Typically, institutions will issue the supplement upon request.

Curriculum, Assessment and Academic Year

The academic year typically begins in mid-September and ends in early July, and is structured with two semesters (fall and spring). The duration of the academic year is 40 weeks, each semester being 20 weeks. An academic hour at higher education institutions is 45 minutes and typically delivered as a two-hour class (90 minutes).

Curriculum design and delivery has traditionally been regulated by the Ministry of Education. State standards are followed for all core courses in all academic programs, with elective course content defined by individual institutions. Elective courses typically make up 25-50 percent of overall program content at both the undergraduate and graduate levels.

Undergraduate and graduate students are assessed using separate systems. A multi-score system is used in assessing undergraduate students, with 100 points representing the maximum score. Weighting is based 50-50 on classroom performance and end-of-semester examinations, with 51 percent overall being a passing grade. At the graduate level, students are assessed on a 5-poing system: Unsatisfactory, Fair, Good, Very Good, and Excellent.

Undergraduate students have to sit and pass final state examinations or defend a thesis in order to be awarded a bachelor degree and a final grade. Upon completion of their undergraduate programs, students may apply to programs at the master’s level. Award of master’s degrees requires the defense of a thesis, which provides access to doctoral studies.

Institution Types

The Ministry of Education lists [22] 52 higher education institutions operating in Azerbaijan, including 31 public and 22 private institutions, enrolling approximately 150,000 students. Private institutions accounted for one eighth of all higher education enrollments in 2011. Most students in public institutions still pay tuition fees, with just 13.5 percent of students receiving state scholarships in 2011/12.

There are three main types of higher education institutions in Kyrgyzstan:

- Universities (universitet) – wide range of specializations, including graduate programs.

- Academies (akademia) – scientific focus, including graduate programs.

- Institutes (institut) – a branch of a university or academy.

Vocational and technical education is provided by vocational schools and culminates in the receipt of a professional diploma. Colleges also provide programs leading to pre-bachelor diplomas (subbakalavr).

Admission to Higher Education

Admission to Higher education institutions is open to graduates of secondary and/or vocational schools or colleges with the relevant diploma of completion (or Certificate of Secondary Education – Orta Təhsil Haqqında Şəhadətnamə).

Admission is carried out on the basis of central examinations set by the State Student Admission Commission of the Republic of Azerbaijan [23] (Tələbə Qəbulu üzrə Dövlət Komissiyası – TQDK). Upon completion of undergraduate studies, students may apply for admission to graduate studies. There is a graduate admissions test administered by the TQDK.

The TQDK sets all admission procedures and standards, and is responsible for placing students based on their performance on the centralized entrance examinations.

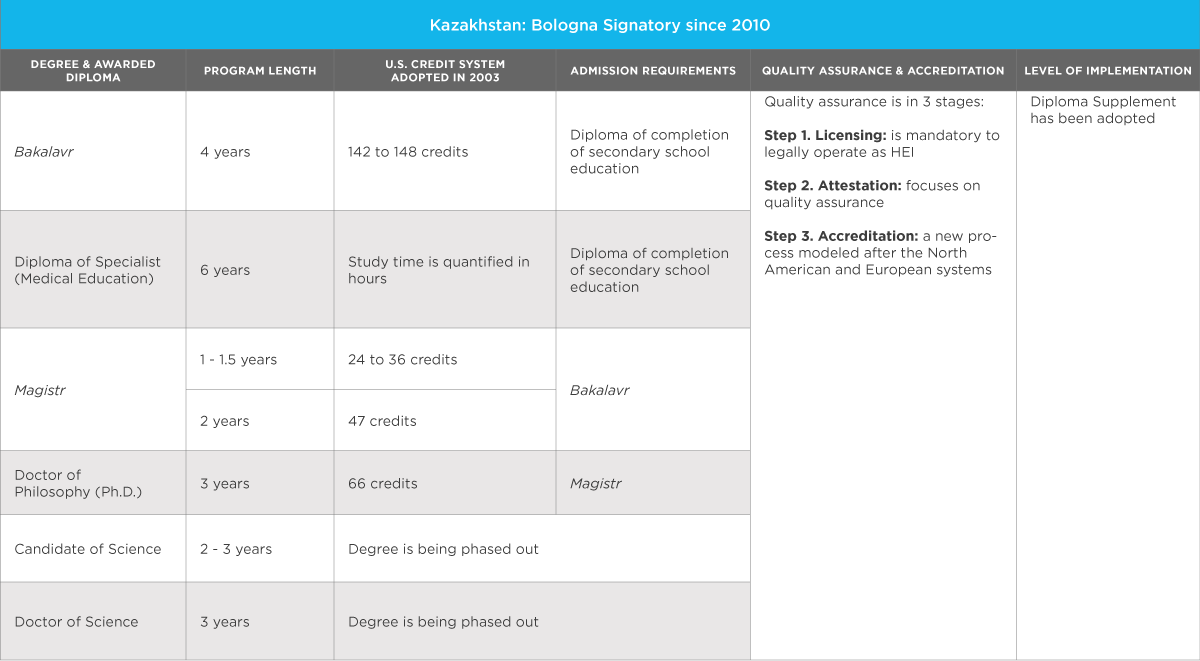

Kazakhstan: Bologna Signatory since 2010

Kazakhstan was the first country in Central Asia to sign and ratify (1999) the Lisbon Convention on the Recognition of Higher Education Qualifications in the European Region [24], an important precursor to, and central instrument of, the Bologna Process. In 2010, Kazakhstan became the 47th member of the Bologna Accords.

The introduction of the three-cycle Bologna system began in 2004, and was written into the Law on Education of 2007, which reflects issues related to the integration of the Kazakh higher education system with the European Higher Education Area.

Qualifications

Higher education is open to students who have completed general secondary, technical and vocational education or further education. In accordance with the Law on Education (2007) institutions of higher education can offer the following levels of education and qualifications:

- Bachelor (Bakalavr): the duration of study is a minimum of four years, or 142 to 148 credits; there are no three-year degrees. Holders of the bakalavr are eligible for admission to master’s and doctoral programs.

- Diploma of Specialist: this is the old Soviet-style qualification and has been kept specifically for medical education. The program is six years in duration and is quantified in hours rather than credits. Admission is based on the high school diploma.

- Master (Magistr): The duration of study is one to two years (24 – 47 credits). Typically, science- and research-based programs are two years in length and aimed at students who are preparing themselves for academic fields. Students must publicly defend a thesis for the award of the academic degree in the relevant discipline. Admission is based on the bakalavr.

- Doctor of Philosophy: The duration of study is a minimum of three years and 66 credits. The Candidate of Science and Doctor of Science are remnants of the old system and are being phased out.

[26]Sample Documents: Kazakhstan [26]

[26]Sample Documents: Kazakhstan [26]

- Bakalavr Degree Certificate in Transport Engineering from Karaganda State Technical University.

- Addendum to the diploma (in original language first and then with English translation). Most institutions in Kazakhstan will issue translated versions of transcripts upon request. The transcript shows course code, course name, credit weighting, and grades (letter, points, percentage and description).

Curriculum and Assessment

Curriculum design and delivery has traditionally been regulated by the Ministry of Education and Science [27]. State standards are followed for core courses in all academic programs offered by both public and private HEIs. However, a greater deal of autonomy over program design and course content has been introduced in recent years, particularly at the graduate level.

Generally, around 50 percent of the total academic workload in all academic programs is mandatory (core) and the other 50 percent is comprised of elective subjects which can be taken at any time during the program of study.

Assessment and progression is based on end-of-year examinations. Internal assessment procedures were introduced on an experimental basis in 2012.

The Ministry of Education and Science awards all degree certificates regardless of institution type.

Institution Types

The type of higher education institution is determined at the licensing stage and depends on the number of programs and orientation of the research work. The following higher education institutions exist in the Republic of Kazakhstan:

- Universities: multi-profile educational organizations, which grant degrees in at least seven professions and conduct fundamental and applied scientific research.

- Academies: offering professional programs, as well as fundamental and applied research programs, typically in one or two specialties.

- Institutes (and assimilated high schools): offering professional programs in one or more specialties.

Between 1993 and 2001, the number of HEIs increased quite dramatically with the legalization of non-state (private) universities. At the beginning of academic year 2011/2012, there were a total of 146 higher education institutions of which 89 were private. Enrollment was split quite evenly between public and private institutions, with 320,000 students attending public institutions and 290,000 attending private schools.

Admission to Higher Education

Admission to institutions of higher education is based on the results of the Unified National Test (UNT) for secondary school graduates and the Comprehensive Test (CT) for mature students, graduates of secondary vocational schools, and graduates of overseas secondary schools. Students are tested in five subjects during the 3.5 hour UNT. Three subjects are compulsory: Kazakh language, Kazakh history, and mathematics. The other two subjects are electives, based on students’ further study interests.

Tests are evaluated on a 125 point scale, and since 2012 the minimum passing score required for admission to an institution of national status is 70 points. For all others, the passing score is 60 points. Applicants with at least 30 points can be admitted to technical and vocational colleges.

Applicants to master’s programs must also take an entrance examination, showing competence in one foreign language (English, French or German), as well as the language of instruction (Kazakh or Russian) and in a specialty.

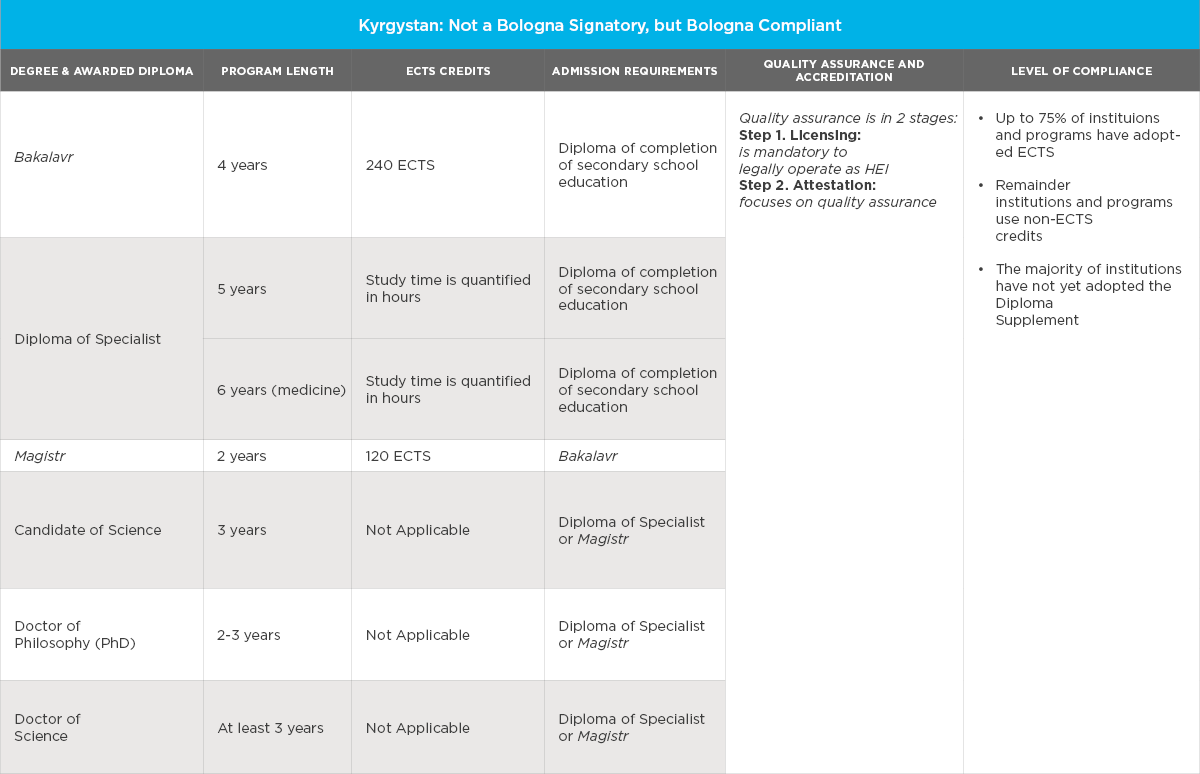

Kyrgyzstan: Not a Bologna signatory, but Bologna compliant

Kyrgyzstan is not a signatory to the Bologna Accords nor is it eligible; however, in August 2011 a government decree on transferring to a two-cycle system of higher education was issued, with course weighting to be expressed in ECTS credits. According to the decree, all HEIs were expected to transfer to the bachelor and master system by the start of the 2012/13 academic year. The implementation process is ongoing, reportedly at about 75 percent across all institutions, but there is said to be some reticence among employers towards recognizing bachelor and master degrees as equivalent to the traditional specialist degree.

Qualifications

Currently, Kyrgyzstan is operating parallel systems of high education, one based on the European model and the other on the old Soviet model. While many institutions are now using the ECTS credit system, few are issuing the Diploma Supplement. The following qualifications are delivered by higher education institutions in Kyrgyzstan:

- Bachelor (bakalavr): the duration of study is four years. There are no three-year degrees offered. Admission is based on the diploma of completion of secondary school education.

- Diploma of Specialist: this is a holdover qualification from the Soviet era and the duration of study is five years (six in medical fields and architecture). Like the bachelor, admission is based on the secondary school diploma. Study time is quantified in hours rather than credits.

- Master (magistr): the duration of study is two years, with admission based on the bakalavr.

- Candidate of Science: the duration of study is three years and ECTS credits are not applicable to this research degree. Admission is based on the diploma of specialist or magistr.

- Doctor of Philosophy: the duration of study is two to three years and admission is based on the diploma of specialist or magistr.

- Doctor of Science: a high level research degree based on the completion of the candidate of science or PhD, requiring at least three years of research-based study.

[29]Sample Documents: Kyrgyzstan [29]

[29]Sample Documents: Kyrgyzstan [29]

- Four-year Bakalavr Degree in Economics from the Kyrgyz University of Economics, with an addendum to the diploma on the first page.

- The transcript on the second page shows the following details: course name, hours studied, credits and grade description.

Curriculum, Assessment and Academic Year

Curricular content at most institutions is based on state educational standards. In accordance with these standards, each program has a mandatory component making up roughly 60 – 70 percent of the total program. Institutions are free to set their own evaluation systems and teaching methods.

Usually, the undergraduate semester lasts for 17-18 weeks and graduate semesters for 15-16 weeks. The weekly workload for students amounts to approximately 54 hours. A single course cannot exceed 30 hours a week.

In the late 1990s, a modular system was introduced in most institutions. It includes a half term and a final evaluation each semester. Since 2004, EU-aided pilot projects aimed at introducing the ECTS have been developed at a number of higher education institutions. Institutions are now required to publicize the ECTS weighting of all programs. One ECTS credit equals 30 academic hours. Each academic hour lasts for 50 minutes. The number of ECTS for full-time students should amount to 60 credits per year (30 per semester).

The academic year begins in early September and ends in June.

Institution Types

In 2011/12 there were 54 higher education institutions operating in Kyrgyzstan, including 33 public and 21 private institutions, enrolling a total of 239,000 students. Private institutions accounted for one eighth of all higher education enrollments in 2011. Most students in public institutions still pay tuition fees, with just 13.5 percent of students receiving state scholarships in 2011/12.

There are four main types of higher education institutions in Kyrgyzstan:

- Universities (universitet) – wide range of specializations, including graduate programs.

- Academies (akademia) – scientific focus, including graduate programs.

- Specialized HEIs (for example, Kyrgyz National Conservatory, Bishkek higher military specialized schools (uchilische)) – narrow focus institution, offering programs at all levels.

- Institutes (institut) – a branch of a university or academy.

International universities – In addition, eight universities are intergovernmental and their activities are overseen by authorities in different countries.

- Kyrgyz-Russian Slavic University

- Kyrgyz-Uzbek University

- Kyrgyz-Turkish University ‘Manas’

- American University in Central Asia

- Kyrgyz-Russian Academy of Education

- Kyrgyz-Kuwait (East) University

- International University Alatoo

- Aga Khan University.

Admission to Higher Education

Admission to higher education is based on a standardized entrance examination – the National Testing System – and the certificate (attestat) of completion of secondary education, secondary professional education or a diploma in primary professional education.

Test takers are graded on a scale of 240 points, with the top 50 candidates receiving full scholarships at the university department of their choice. Other applicants may apply for institutional grants. There are three rounds to the admission process and applicants have the opportunity to apply to several universities to increase their chances of gaining admission.

The system of government funding has improved since the introduction of the National Testing System in 2002. The universal admission test is open to all secondary school graduates, is free and offered in all regions of the Republic. Prior to the introduction of the standardized test, universities were allocated quotas by the government and independently distributed their share of scholarships. The system was highly criticized for being discriminatory, corrupt and ineffective. The National Testing System has generally been praised for improved access to free education for young people from remote districts.

The test is conducted annually at the end of May, with results issued in mid-July.

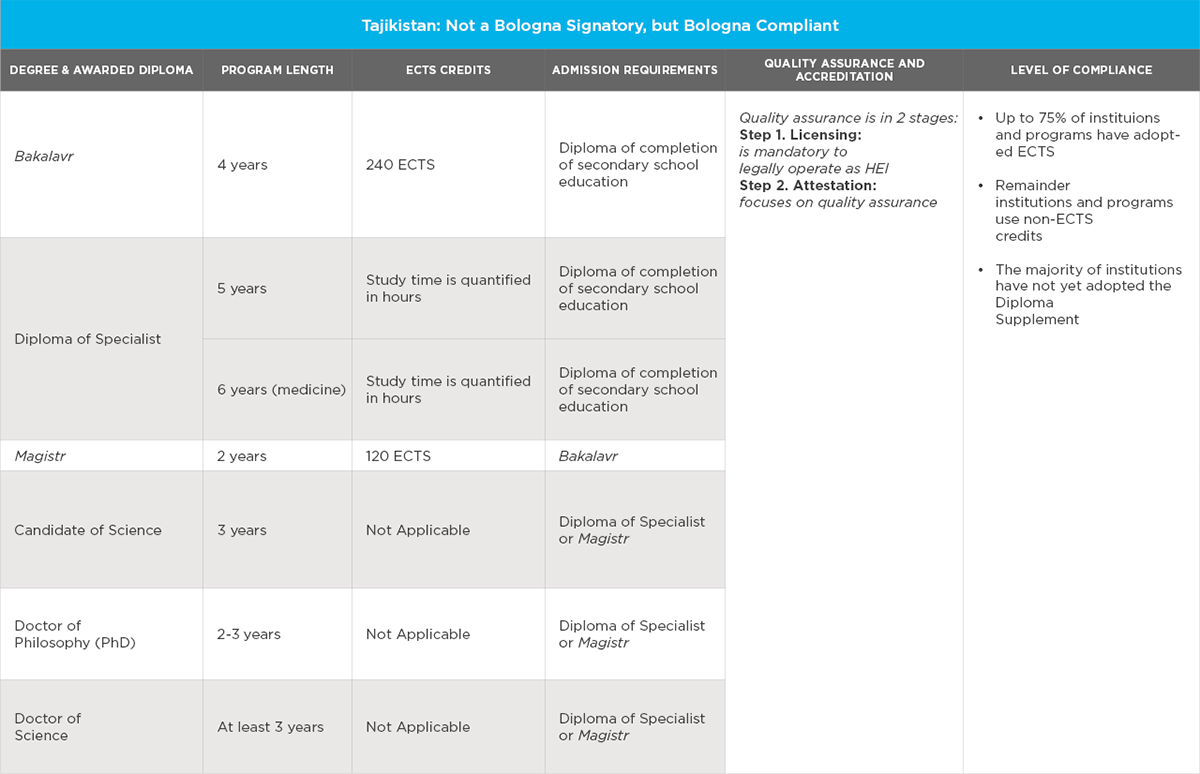

Tajikistan: Not a Bologna signatory, but Bologna compliant

The Tajik government signed and ratified the Lisbon Convention on the Recognition of Degrees in 2012. As in Kyrgyzstan, the Tajik authorities are trying to align their system of higher education with that of the Bologna model. The government has introduced the ECTS credit system as a pilot program in two universities – the Technological University of Tajikistan and the Tajik University of Commerce – and has a target of widespread adoption by 2020. A number of new policy documents stress the importance of aligning with the Bologna Process.

Qualifications

As in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan is currently operating parallel higher education systems, one based on the European model and the other on the old Soviet model. While many institutions are now using the ECTS credit system, the Diploma Supplement is yet to be adopted. The following qualifications are delivered by higher education institutions in Tajikistan based on the National Standards for Higher Professional Education:

- Bachelor degree (darajai bakalavr): studies last four years (240 ECTS) except for medicine (no less than five years/300 ECTS). Admission is based on the completion of secondary school education.

- Master’s degree (darajai magistr): studies last a minimum of two years (120 ECTS). There are no one-year master’s degrees. Admission is based on completion of the bakalavr.

- Diploma of Specialist (darajai mutakhassis): studies last no less than five years and six years in medicine. This degree is still being offered and is a remnant of the Soviet system. Admission is based on the completion of secondary school education.

- Candidate of Science degree (aspirantura): studies last three years and entry is based in the diploma of specialist or magistr.

- Doctor of Science (doctorontura): this is the highest award in the Kyrgyz system, with studies lasting three years and entry based on the candidate of science or doctor of philosophy.

- Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.): Recently introduced and with studies lasting two to three years.

Currently, to obtain a doctor of science degree candidates need to go through the certification commission (Visshaya Attestacionnaya Commisia – VAC) in Russia, and have dissertations translated into Russian. This is proving increasingly problematic with Russian now essentially a foreign language in Tajikistan.

[31]Sample Documents: Tajikistan [31]

[31]Sample Documents: Tajikistan [31]

- Specialist Diploma from the Technological University of Tajikistan. The transcript shows course names, hours undertaken, and grades achieved.

Curriculum, Assessment and School Year

The compulsory minimum content for undergraduate degrees and the level to be achieved in different specialties are outlined in the National Standards for Higher Education. According to these standards, the maximum workload for students should not exceed 54 hours per week, including contact hours and self-study.

The academic year runs from early September to early June, with winter examinations at the end of the first semester (end January) and summer examinations at the end of the year.

Institution Types

There are three main types of higher education institution operating in Tajikistan:

- Universities (donishgoh)

- Academies (akademiya)

- Institutes (donishkada)

Currently, universities and academies offer bachelor, master and specialist degrees whereas institutes offer only bachelor and specialist degrees.

Universities offer a wide range of specializations and carry out fundamental and applied research. Academies also offer research programs, but in a limited number of fields. Institutes provide education in one or a select number of fields.

Since independence, the total number of institutions of higher education has grown from 13 to 30 (2012). There are no private institutions. Total enrollment was approximately 155,000 in 2012.

Admission to Higher Education

Admission to institutions of higher education is based on competitive institutional admissions tests, with general standards set by the Ministry of Education. Students must have completed general or vocational/professional secondary education to apply for entry to an institution of higher education.

A National Testing System (NTS) for university admission was scheduled to be introduced in 2010 (pilot phase) but due to funding constraints was delayed until 2014. The National Testing Center, responsible for the test, operates under the Ministry of Education. It is hoped that the new admissions test will help promote equal access to higher education, improve standards, and reduce corruption.

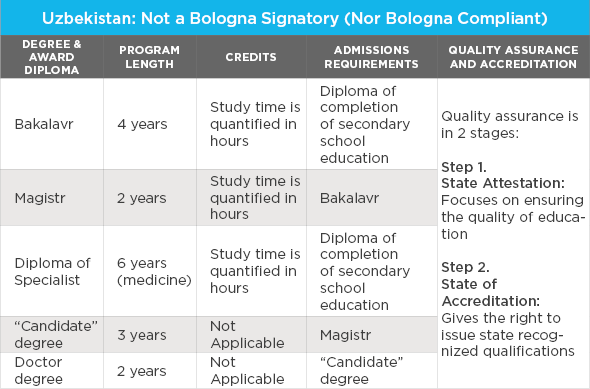

Uzbekistan: Not a Bologna signatory (nor Bologna compliant)

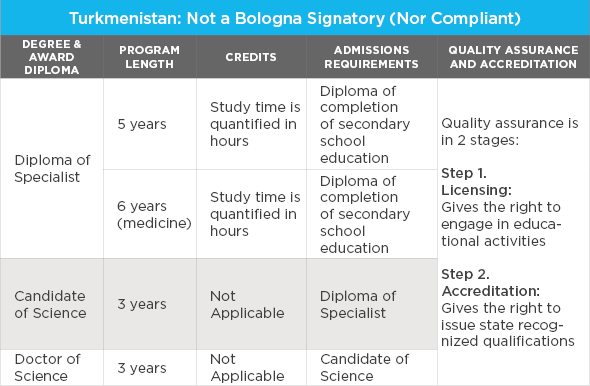

Turkmenistan: Not a Bologna signatory (nor compliant)

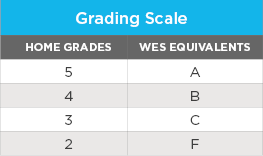

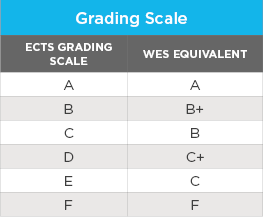

Grading Scales

The most common grading scales that we see in these countries are the old Soviet 2 to 5 scale and the new ECTS grading scale, which runs from A to F.

WES Document Requirements

In Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, WES requires that academic transcripts be sent directly for evaluation by the institutions attended. WES reserves the right to verify those documents again, if needs be.

For Azerbaijan, all documents must be verified by apostille through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Azerbaijan. And for all Kazakh documents, they must be verified by apostille through the Ministry of Education and Science.

The apostille process is an agreement through the Hague Convention that most countries in Europe are signatory to under which state issued documents in one signatory country should be recognized in another. The United States is also signatory to this Convention, but Canada is not. If it is not possible to verify documents through the apostille process, then they must be verified directly with the awarding institution, which is typically a lengthy process.

If official documents are not issued in English, WES requires a precise word-for-word English translation.