Jessica Magaziner, Credential Analyst, WES

The Syrian conflict has been covered extensively in the news since its violent inception in the spring of 2011. This conflict has resulted in extreme loss of life, societal destruction and the displacement of millions of Syrian people. While the global response has focused on addressing the most immediate needs of Syrian refugees (food, shelter, medical attention and primary education), other less obvious impacts of the conflict are becoming evident. The displacement of such a vast number of young Syrian people has made them unable to pursue their higher education studies, resulting in a “lost generation” of students—students without the financial means or the institutional access to continue their education. Education that will be desperately needed to help rebuild Syria after the conflict has ended. This issue has come to the forefront of the news in recent months and efforts are being made by governments and non-governmental agencies around the world to address it, some to greater effort and effect than others.

Syrian Conflict

Since the beginning of the Syrian Civil War four and one-half years ago, 250,000 Syrians [1] have died and over 11 million people have been displaced. The conflict began with pro-democracy protests and later intensified into a civil war. While the conflict began as opposition between the supporters of President Assad and those that demanded his removal, it has developed “sectarian overtones [1]” involving various jihadist factions (including ISIS). Horrific violence has been perpetrated by individuals on all sides of the conflict, though the involvement of jihadist groups has escalated much of the violence to include rape, torture and the use of chemical weapons. This crisis has forced many Syrians from their homes and has driven them across the borders in increasing numbers to neighboring countries as the situation has worsened. The conflict remains unresolved despite efforts of key international players to find a political solution. The toll of this conflict on the Syrian population has been extremely devastating. From the loss of life, to the displacement of a majority of the population and the devolution of the state infrastructure, it is hard to imagine how Syria and its people will recover.

Refugee Crisis

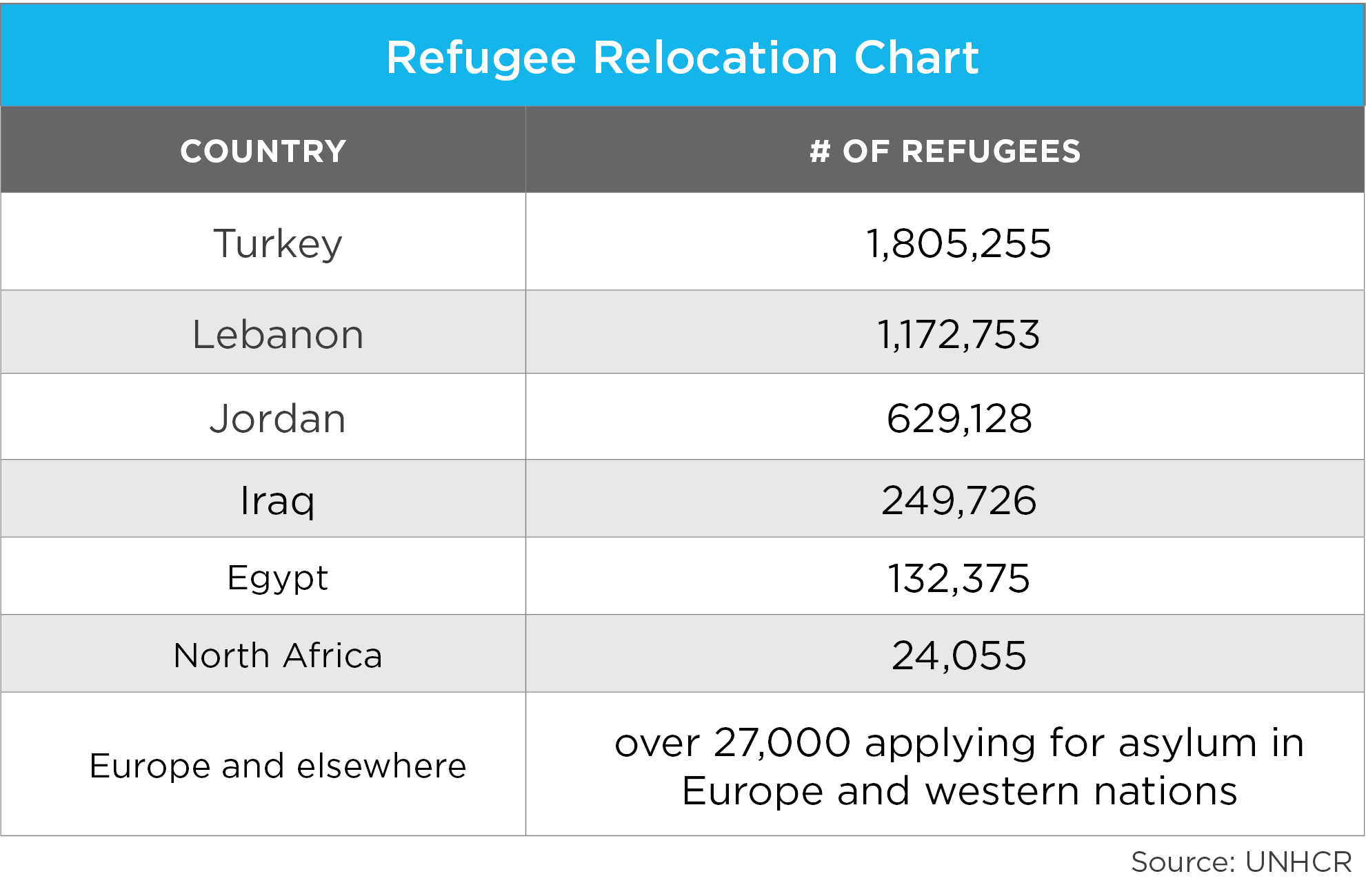

Within Syrian borders, 13.5 million people [2] are in need of humanitarian assistance, with, some 4.5 million [2] located in hard to access areas. The conflict has entered its fifth year and the number of refugees is growing rapidly, with a prediction of 4.27 million [3] by the end of 2015. This sealed its fate as “the world’s single largest refugee crisis [3] for almost a quarter of a century under UNHCR’s mandate.” Syrian refugees are spread primarily throughout the Middle East and North Africa (see Refugee Relocation Chart below). Refugee camp conditions are worsening and poverty is rampant, which has caused refugees to seek asylum further away (particularly in Europe).

The Institute of International Education (IIE) has estimated that 450,000 [4] of these refugees are of university age (18-22 years old) and around 100,000 of those people [5] are eligible to enter university. Only a very small percentage of these students has been able to continue higher education in their host countries. This has created a “lost generation [6]” of university students for Syria, an issue that has lasting implications for the country’s future.

Importance of Higher Education in Post-Conflict Societies

It is easy to look at this overwhelming refugee crisis and ask why should higher education be a priority, when there are so many other issues to address? While the physical needs of the refugees is the paramount priority, the academic needs of the Syrian people cannot be overlooked. It is imperative that higher education be viewed in a strategic context, as a way of recovery for a war-stricken nation.

The lead author of a report [6] on Syrian students and scholars in Lebanon, Keith David Watenpaugh, has highlighted the need to educate Syria’s young people and give them a stake in rebuilding their country. In an interview by the University of California Davis College of Letters and Science with Watenpaugh, he states that “the war will end but the young people who would be integral in rebuilding the country are being left behind [8].” Watenpaugh argues for the necessity of increased research and aid provided for the university-age (18-24 years old) subset of the population to help post-conflict countries rebuild successfully.

In a Brookings Doha Center Policy Briefing [9], Sansom Milton and Sultan Barakat discuss the ability of higher education to effect positive change in post-war situations. “Higher education, when properly supported, acts as a catalyst for the recovery of war-torn countries in the Arab world, not only by supplying the skills and knowledge needed to reconstruct shattered economic and physical infrastructure, but also by supporting the restoration of collapsed governance systems and fostering social cohesion.” Without proper education of this young generation of Syrians, they will be unable to contribute to the reconstruction of their nation.

Milton and Barakat also argue that engagement in higher education allows young men and women a form of protection from conflict and reduces the likelihood of them joining violent organizations. Investing in higher education could potentially transform post-conflict societies, particularly in the Middle East. This underlines the need for international policy changes regarding higher education and its pivotal role. These changes would involve greater protection of academic institutions in times of war, increased university networks to promote academic solidarity and more funding to rebuild higher education in the aftermath of conflict.

It is crucial to remember that this issue does not affect Syrian refugees alone. Johannes Tarvainen, an education officer at UNHCR, estimates [10] that one percent of all refugees worldwide have access to higher education. This issue also affects refugees from Somalia, Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sudan [10].

Obstacles

Funding

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) requested 5.5 billion dollars [3] for Syrian refugee funding in 2015, though only approximately 40 percent of that has been allocated thus far. This has resulted in restrictions of food allocations, medical care and primary education services. The longer the crisis drags on, the more difficult it becomes for neighboring countries to handle the influx of refugees and provide continuing support.

International Response to Refugees

While Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan have taken the vast majority of refugees, neighboring Gulf States like Saudi Arabia, Qatar, United Arab Emirates and Bahrain have not provided any shelter for refugees. Russia, Singapore, Japan and South Korea have also been hesitant to allocate financial resources or promise resettlement for Syrian refugees. In some cases, this may be due to safety considerations. The United Kingdom has pledged to take 20,000 [11] refugees over the next five years and the United States has raised its number of incoming Syrian refugees to 10,000 for 2016 [12]. Both countries have demonstrated concern that incoming refugees may not only be there for their education and safety, but as threats to national security. In light of recent terrorist attacks, these concerns have remained at the forefront of the news. Many refugees have reached the border states of Europe, overwhelming them with an influx of people, which is now being met with resistance [13]. The international community, which is best suited to tackle the higher education need for refugees, has been overwhelmed by addressing the more basic needs of refugees and security concerns for their borders. Higher education is not considered a priority.

Document Requirements and Language Barrier

Many refugees lack identification documents or academic transcripts needed to transfer to a new institution. This makes it difficult to evaluate their educational background. Other roadblocks that prevent Syrian refugees from accessing higher education in their host countries include language barriers and “political tensions [10].”

Current Efforts

The international response to this educational crisis has been varied. It was initially viewed as primarily a need for humanitarian aid and Syrians who took refuge elsewhere did not anticipate being away from their homes for years to come. In recent months, the increasingly high number of refugees attempting to enter Europe has shone a new light on the severity of the Syrian crisis.

European Union

While the European response to the plight of Syrian refugees has been slow, a new wave of aid has shown a change in policy. Hans de Wit and Philip G. Altbach, professors and directors of the Center for International Higher Education at Boston College, propose that Syrian refugees are receiving a more positive response than other refugee group for a variety of reasons [15]. De Wit and Altbach suggest that due to the Syrian refugees’ status as “political victims” rather than economic ones, they are receiving more international sympathy. Syrian refugees are viewed as better educated and therefore less of a burden to the host community. It is presumed that the refugees would have an easier time integrating into the new culture and job market. This has inspired the view of Syrian refugees as potential talent and “assets for Germany and other European countries in the short and particularly the longer term [15].”

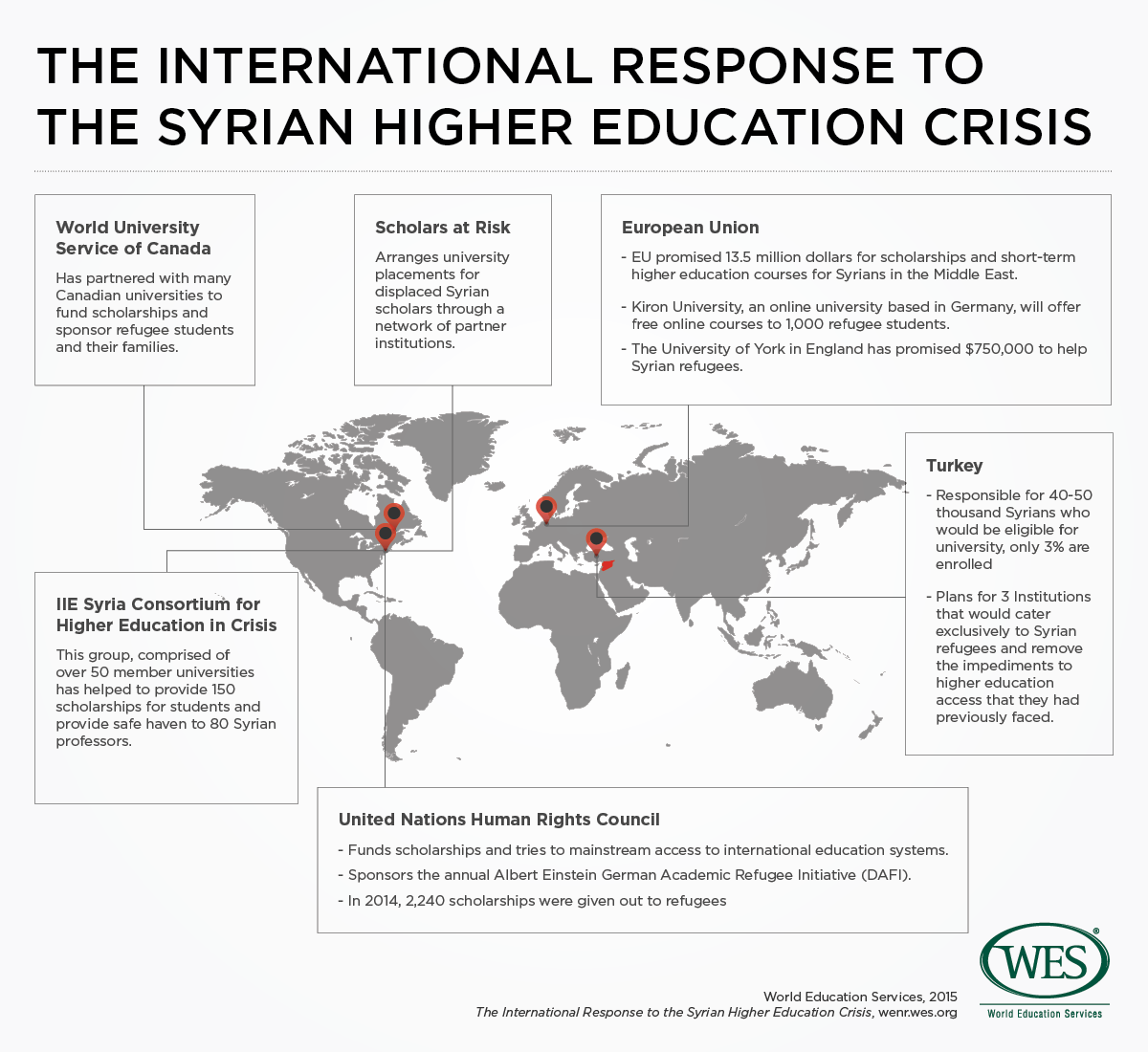

The European Union promised 13.5 million dollars for scholarships and short-term higher education programs for Syrians in the Middle East. Germany has been very vocal about helping Syrian refugees. Kiron University [16], an online university based in Germany, will offer free online courses to 1,000 refugee students. The students can be based anywhere in the world and just need proof of refugee status and an internet connection to apply. The University of York [17] in England has promised $750,000 to help Syrian refugees. This would help to sponsor academics as well as provide scholarships to undergraduate students.

Canada

Many Canadian universities have responded to the need for aid in this crisis. The World University Service of Canada [18] has partnered with many universities to fund scholarships and sponsor refugee students and their families. The list is long, but includes Ryerson University, University of Toronto, York University, Algoma University, Trent University and the University of Regina, the University of Alberta and Western University. In addition to this financial help, the University of Ottawa is offering legal support to Canadians who want to sponsor refugees themselves. The university has also developed a free certificate program [19] with the American University of Beirut in Lebanon focusing on community mobilization.

Middle East

Turkey is responsible for between forty and fifty thousand Syrian refugees [20] who would be qualified to enter university, of which only around 3 percent are enrolled. To help address the need for higher education access for Syrian refugees living in Turkey, three proposals have been introduced. New institutions have been proposed that would cater exclusively to Syrian refugees and remove the impediments to higher education access that they had previously faced.

Zakat University [20] was developed by the Zakat Foundation of America. All of the academic instruction will be in Arabic, removing the language barrier faced by many refugees who are not proficient in Turkish. This university has been constructed and is awaiting its first group of students to begin their studies. Turkey Qatar University [20] is a plan developed as an institutional partnership between the Turkish and Qatari governments. It will aim to aid refugees and create opportunities for scientific collaboration between the nations. The Middle East Peace University [21] is a proposal developed by Turkish educational entrepreneur, Enver Yücel. This institution will strive to give Syrian refugees the education they need to make them more competitive in the Turkish job market.

The idea of Syrian-only institutions is not universally accepted as the best solution. Some fear [20] that this would alienate students in their new environment. As the Syrian conflict remains protracted, students face the likelihood of being in a new country for an extended period of time. This makes cultural integration a necessity, something that would not be addressed by Syrian-specific higher education institutions.

Another concern is the status of these new institutions. As there is currently no official accreditation status for them, the quality of their educational instruction and the employment opportunities after graduation remains unclear. A potential solution to this would be to create partnerships with accredited institutions, which would then award Syrian students with accredited degrees, but no formal agreements have been struck. The effect of these proposals remains to be seen as much funding and monitoring is required in order to get them implemented.

UNHCR

The refugee branch of the United Nations funds scholarships and tries to “mainstream access to international education systems. [10]” This involves offering scholarships and higher education programs to those living in refugee camps. These programs use a combination of online coursework and in-person teaching. UNHCR also sponsors the annual Albert Einstein German Academic Refugee Initiative (DAFI) [22]. This is a scholarship program for refugee higher education funded by the German government. The focus of the program is to help the students to “achieve self-reliance; develop qualified human resources; support the refugee community; facilitate integration; and serve as a role model.” In 2014, 2,240 scholarships [10] were given out to refugees from around the world.

Non-Governmental Organizations

Some non-governmental organizations have been able to bring higher education access for refugees to the forefront of their international agendas. This allows resources to be allocated to fund or provide access to scholarships and earmark money for logistical costs.

The German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) has provided scholarships to Syrians and Jordanians living in areas highly impacted by Syrian refugees in Jordan. These scholarships will cover living expenses and additional courses on “topics like good governance and civil society [4].” These courses focus on aiding the Syrian refugees in how to rebuild their country after the conflict has ended. There are many other resources [23] for scholarships, however, the demand greatly exceeds the supply.

One of the most prominent organizations trying to address this academic crisis is the IIE Syria Consortium for Higher Education in Crisis [24]. This group, comprised of over 50 member universities (many from the U.S., but also Europe, Latin America and the Middle East), is addressing the needs of both students and scholars to continue their study and research in safe environments. It has helped to provide 150 scholarships for students and provide safe haven to 80 Syrian professors through IIE’s Scholar Rescue Fund [25]. These numbers may seem low in comparison to the great demand, but it is estimated that fully funding a Ph.D. student costs around $77,000 [26] a year.

A New York-based non-governmental organization called Scholars at Risk (SAR) also tackles the issue of higher education for refugees through a network of partner institutions. They have a three-pronged approach [27] of “protecting threatened scholars, preventing attacks on higher education communities and promoting academic freedom worldwide.”

In a statement to World Education Services from Rose Anderson, a SAR program officer in Protection Services, the challenges that the organization faces in its work to place Syrian refugees was highlighted. One of the most pressing demands is trying to address the growing numbers of scholars in need. Ms. Anderson stated that prior to March of 2011, SAR had only received 11 applications from threatened Syrian scholars. The organization has currently received 150 applications from Syrian scholars. “The greatest challenge in our protection work is the great need we are seeing, especially from Syrian scholars. In partnership with our network we arrange 80-100 positions a year, but we are now receiving roughly one application a day from scholars in need of help. We are grateful to our members who have already hosted Syrian scholars and to those who have committed to do so, but as a network, we still seek to do more.”

She also expanded on the need to invest in their education and continued academic research. “We are at risk of losing the current generation of scholars and students from Syria, Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East. When this conflict ends, the effects on the country and its higher education community will be felt for decades to come. Quite simply, each scholar and student that we lose now deepens the challenge of restoring the region when the violence eventually subsides. We, and the scholars we work with, hope that one day when the situation in Syria is stabilized, they can return to their region to help it rebuild. In the interim, we are trying to help as many scholars as we can to find positions of safety where they can continue their important work and contribute to their own host communities and countries in the process.”

Even after placements at universities have been secured, SAR still faces issues relating to immigration and providing safe transportation for the threatened scholars. “In our work seeking positions of refuge for Syrian scholars, many of the challenges we face are logistical, such as securing safe and reliable communications with scholars currently in Syria. Other challenges are related to immigration and work authorization issues once a position of refuge has been identified. This requires creativity and sometimes an alternative option for these older children.”

Future Solutions

In order to prevent an educational crisis of this degree in the future, measures have been outlined that would change the way higher education is viewed (not as a luxury, but as an investment in that nation’s future).

Universities are in a unique position to help Syrian refugees pursue higher education. They have the ability to bypass bureaucratic inefficiencies, prioritize Syrian applications and provide facilities for students and their families. Universities are able to waive certain requirements and allocate social services as needed for the students. The president of IIE, Allan E. Goodman, has stated [10] that it “would be a game changer if every college and university in America agreed to take a Syrian student.” Watenpaugh also pointed out [10] how useful the participation of U.S. universities would be. “What would be really great would be programs where American universities create relationships with universities in the region, where we help finance the tuition of students for a couple of years and then maybe they can come to the United States for another year. The ultimate goal I would like to achieve is that U.S. higher education bears some of the burden.”

De Wit and Altbach propose [15] that this is not merely advantageous for the refugees, but for the profile of the university as well. It is a way to internationalize the campus, which would make it more competitive as a higher education institution.

Another necessary step to be taken by higher education institutions and non-governmental organizations is to develop a strong joint network [15]. This would help to protect academic institutions in the face of future conflicts and provide rapid responses [26] to help support the students and faculties of these institutions, whether by directing global attention to their plight or moving them to new locations. This type of network would also be able to anticipate the needs of these communities and provide the necessary cultural and language training [15] that a move would necessitate.

It has become clear that merely providing scholarships or exempting Syrian students from paying tuition are not sufficient. Goodman argues [10] that “scholarship is not enough” due to the hidden costs of attending university in the United States or Europe. “It’s relatively easy to get compassionate universities and colleges to say we’ll forgo tuition, but what we have to come up with is the airfare and ticket to get them out of Syria or out of the camp to the U.S. or to Europe and the living expenses while they’re a student. It’s not enough just to say ‘tuition-free’ or go to countries where tuition is free. You’ve also got to have the resources for that supplemental grant.”

In allocating funds for Syrian students and scholars to attend western universities, the transportation costs, additional school fees (books and other materials) and day-to-day living costs must be acknowledged. The emotional well-being of the incoming students is also key and would require adequate resources for the counseling of traumatized refugees [6].

In order for all of these steps to be taken, it is necessary for the international community to view higher education as a priority for refugee students, not a luxury. In a statement to World Education Services, Hans de Wit expanded on some of his points on why the academic needs of refugees are more important now than ever. “Higher education for these refugees should not be considered as a challenge but as an opportunity. Further education and professional development for these refugees makes it possible to provide them with perspectives as immigrants and/or when they return to their countries. Education in general, and in this case higher education specifically, is a much more effective form of dealing with their presence than putting them in camps without providing them with any other perspective than to wait for approval of their status or of sending them away. The tragic events in Paris should not lead the receiving countries to close the borders, something which is not likely to be successful anyway, but to invest in these refugees’ education and in providing them with a perspective. It is lack of education and perspective that creates terrorism, so why ignore them and produce that option.”

Conclusion

The need for investing in higher education for Syrian young people has been demonstrated, but achieving this is clearly easier said than done. Resolving this educational crisis will not be easy and requires the cooperation and prioritization of funds and efforts by many organizations.

The resolution of the Syrian conflict remains out of reach, but what can be addressed in the meantime is the educational advancement of Syria’s youth. The only future for a reconstructed Syria lies in their hands.