Jessica Magaziner, Research Associate, WES

This article, which focuses on students in Ukraine, is the first in a periodic World Education News & Reviews series that will springboard off of the insights of credential evaluators at World Education Services (WES) to highlight the challenges faced by students in specific regions around the world.

In recent months, the academic and humanitarian communities have begun to focus on the challenges facing the roughly 100,000 university-age and higher-ed-eligible Syrian students now at risk of academic shut-out. But similar, credential-related challenges face aspiring international students from hotspots all around the world. Where are they from, and what difficulties do they face?

Document specialists at WES are well positioned to identify emerging trends and ongoing challenges. One such area is Ukraine, where tertiary students suffer extreme, conflict-related limitations to academic mobility and educational progress across borders.

Ukraine’s International Students

The top four destinations [1] for outbound students from the region have historically been Poland, the U.K., Canada, and the U.S. According to the D.C.-based Migration Policy Institute (MPI), “More than 23,000 Ukrainian students had left to study at Polish universities in the first few months of 2015, 50 percent more than in 2014.” The most recent Open Doors Report from “the Institute of International Education reported 1,551 Ukrainian students in the U.S. during the 2014/2015 academic year, up from 1,464 the year prior. Some 1,535 Ukrainian-origin students received Canadian study permits in 2015, up from 1,294 the year prior.

Background

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine has been split by ethnic and linguistic divisions. The western regions are typically Ukrainian-speaking and look towards Europe for future growth. Residents of the south and east are predominantly of Russian extraction, and are, from a political perspective, aligned accordingly.

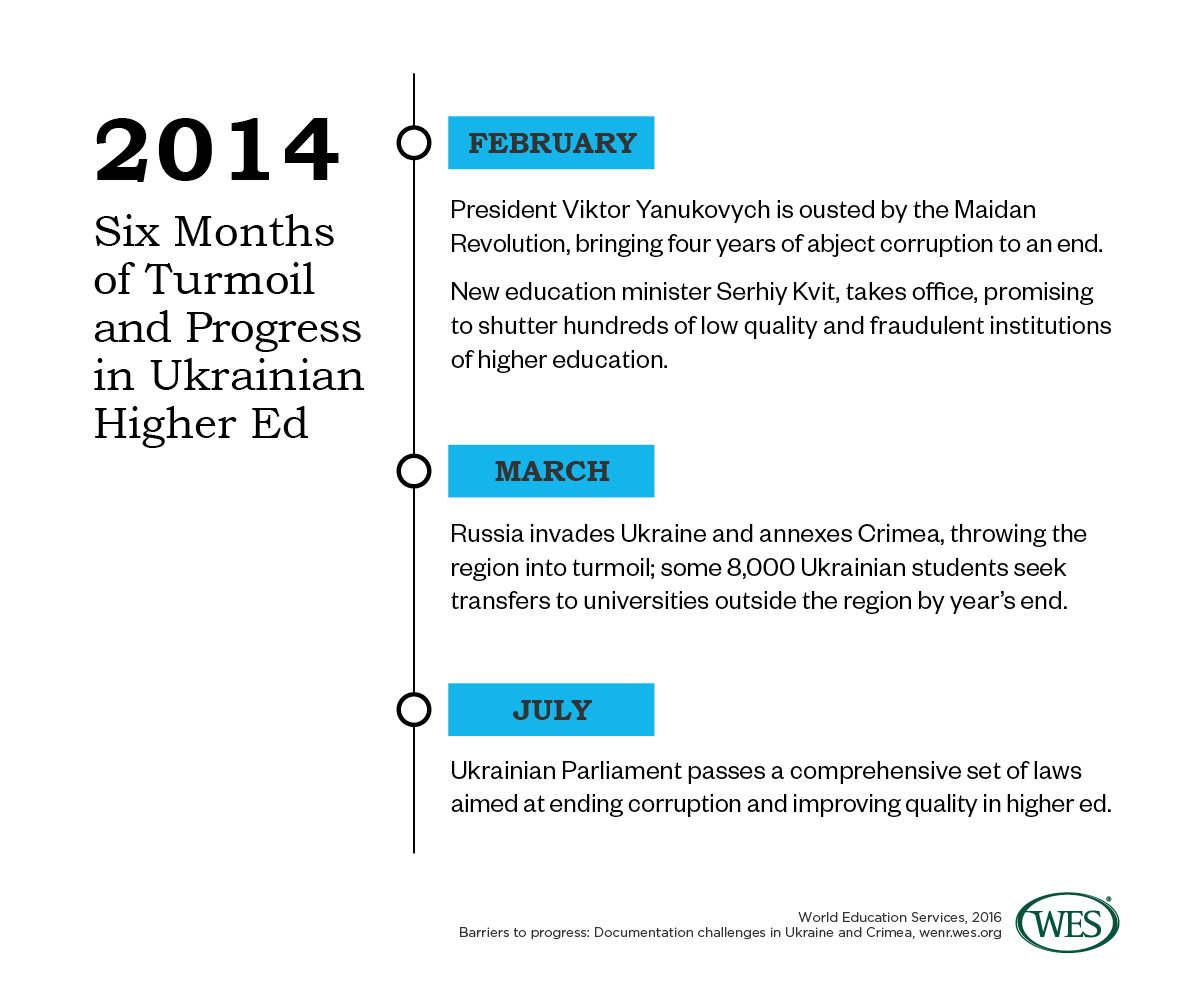

The first two decades of Ukrainian independence saw deepening divisions, that finally erupted into a series of popular protests in late 2013. In February 2014, pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych was ousted and replaced by a pro-Western government. Over the next two months, Russia first invaded – and then annexed – the Crimean Peninsula. In May of 2014, contentious territorial disputes led to the declaration of two self-proclaimed independent territories: the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Luhansk People’s Republic.

The schism’s impact has been dramatic, with an estimated 1.67 million people displaced internally and thousands dead. The chaos has also had a lasting impact on the ability of Ukrainian students to obtain official academic records. This severity of disruption varies by geography: Among students in government-controlled regions, access to verifiable documents remains relatively routine. For those in conflict zones and Crimea, document-related challenges can be severe.

Different Regions; Different Impacts

The Government-Controlled West

In June 2014, Ukraine’s newly installed, pro-Western government passed a significant higher education reform package [3]. The reforms [1] granted greater autonomy to higher education institutions, and created a new national agency focused on quality assurance. They also targeted sub-par institutions, seeking to shutter those that were deemed unsatisfactory. In 2015, education minister Srhiy Kvit [4] noted that the administration had, in the space of a few months, winnowed the number of Ukrainian higher education institutions from 802 to 317 [5], and planned to cut even more deeply.

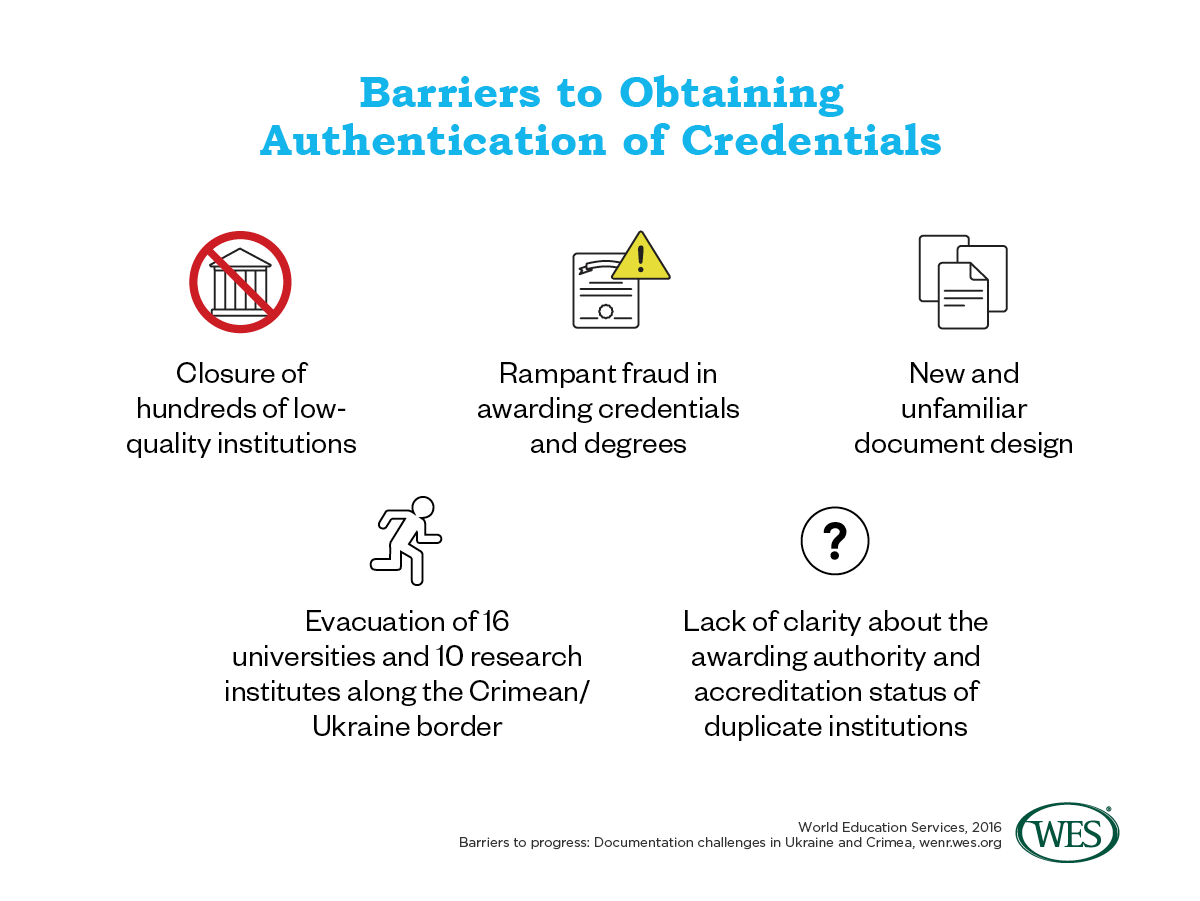

This latest reform is the most recent step in efforts that go back more than a decade. In 2005, for instance, Ukraine signed on to the Bologna Process [6]. In 2007, the government rolled out a new evaluation system, called external independent testing [7] (EIT) intended to combat corruption in the university admission process. In contrast to similar reform efforts in other countries, the EIT has had relative success [8] in terms of reducing fraudulent admissions, if not other, more deeply rooted varieties of fraud. In fact, fraud and corruption remain embedded [9] in the Ukrainian higher education system. Research released in September 2015 found that bribery in exchange for higher grades and diplomas was commonplace. “Many focus group participants suggested that the process of obtaining grades was quite simple,” wrote the authors. “In professional education programs, including medical, law, and business schools, the problem appears to be more widespread and allegedly extends to virtually all courses.”

Although the process for obtaining credentials is relatively straightforward, the impact of this rampant fraud is, for anyone seeking to study or work outside government-controlled Ukraine, highly problematic since the validity of Ukrainian diplomas and other education credentials are highly suspect. One case in point is Saudi Arabia, which no longer recognizes [10] medical credentials obtained at Ukrainian institutions citing “below average” qualifications of graduates.

The Conflict Zone

Two years after the breakaway, life in the regions closest to the independent republics of Donetsk and Luhansk remains difficult [12]. In 2016, tensions began to escalate again [13] after a period of quiet, and one recent British Council briefing paper [5] noted “severe disruptions of universities in the conflict zone.” Such disruptions have been ongoing, and, from the perspective of those trying to further their education outside the country, often devastating. “In 2014,” noted the brief, “8000 students sought transfers to universities outside the region. [Higher education institutions] were also seeking evacuation and, by August 2015, the Ministry had evacuated 16 universities and 10 research institutes.” Many universities were forced to completely abandon [14] their facilities and move to new locations.

WES credential analysts have seen first-hand the effects of university evacuations on the ability to obtain academic documents. Applicants seeking WES evaluations have cited difficulties in accessing their Ukrainian academic documents because university archives may not have been transferred during the evacuation process. In cases where abandoned campuses are now under the control [15] of separatists, obtaining academic records could prove to be impossible.

The independent territories, meanwhile, have instituted their own education ministries and developed new academic document formats, and a number of higher education institutions continue to operate without recognition outside the territories. The existence of “clones [16]” of evacuated universities amplifies the confusion. These institutions operate in conflict zones under the names of institutions that have moved to government-controlled areas. Most operate without any accreditation. This creates a particularly challenging situation for students whose degrees are essentially worthless within Ukraine and the European zone. Although many of these students hope [17] that their degrees will be recognized within the Soviet sphere, there is no guarantee [18] that those hopes will pan out.

Crimea

Two months after annexing Crimea, Russia’s Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev issued a directive [19] commanding the creation of the Crimea Federal University. Officially recognized by the Russian Ministry of Education and Science in 2015, the new university merged seven formerly separate institutions. Other institutions in the Crimea are now defunct or operating in new locations. Many now produce academic documents in a new format typical of those issued by Russian institutions.

The impact on students’ ability to obtain the documents they need to study outside Crimea is variable: Students who attended institutions that have closed, merged or moved, often find it difficult, or even impossible, to get authenticated academic documents. New document formats, meanwhile, create confusion among receiving institutions unfamiliar with the new formats.

The Road Ahead

Two years after Ukrainian independence, the challenges for students from all regions of Ukraine and Crimea remain significant. The high incidence of institutional closure, the easy availability of fraudulent documents, confusion about new degree formats, and the existence of duplicative institutions—all are issues that WES evaluators have seen pose delays and challenges for students, and the need for special care among evaluators.

Special thanks to WES credential specialist, Andrey Bush, for his contribution of specialized Ukrainian documentation knowledge.