Hans de Wit, director of the Center for International Higher Education (CIHE) at Boston College

International student mobility is driving the agenda of higher education now more than ever. Numbers are rising, from 2 million globally mobile students a decade ago to close to 5 million now to an anticipated 8 million in another decade. As a group, these highly mobile students are viewed as a rich economic resource, with a strong focus on their revenue-generating potential manifest in national and institutional policies around the globe.

Taking the long view

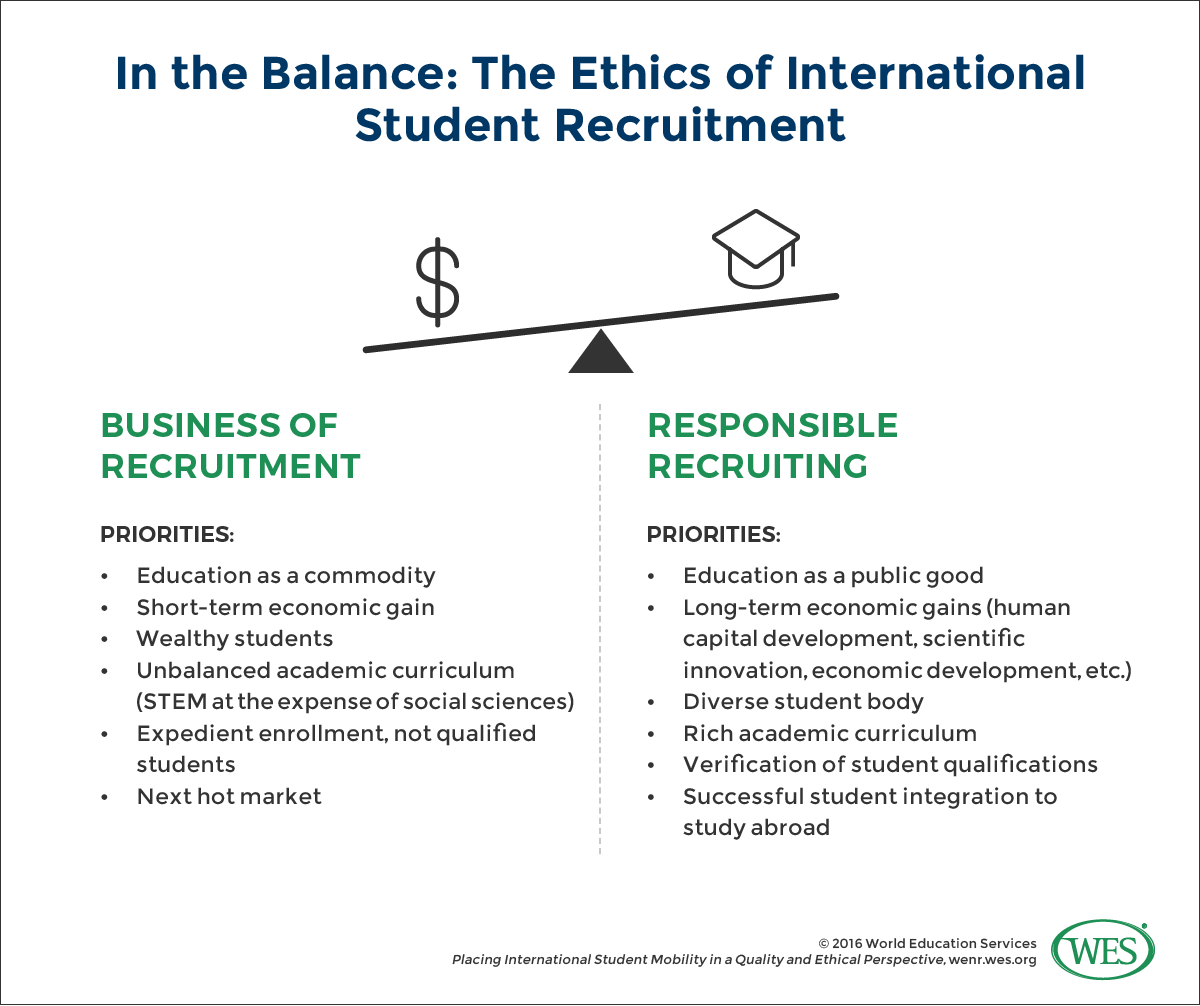

Too often, international students are viewed as “cash cows” and valued for the direct economic contributions they make to individual institutions and the communities in which they live.

But that view entails multiple risks and misses the far greater benefits that a strategic approach to international student recruitment can generate. These include:

- Significant scientific collaboration and research opportunities

- Human capital development that benefits the economies of both receiving and sending countries

- Long-term economic development

- Exposure to global perspectives among domestic students who cannot afford to study abroad

A nuanced understanding of these longer term payoffs is critical to the development of a comprehensive internationalization strategy that benefits students (local and international), institutions, academia, national and regional economies, and civil society alike. (For more, please see Internationalizing Higher Education: Worldwide National Policies and Programs [1], Robin Matross Helms, 2015)

Institutions worldwide compete mightily for these students’ interest and tuition dollars; many also struggle with the ethical, social and cultural ramifications of their successes. Governments and international agencies proudly publish reports touting both their competitive prowess, and the contributions that international students make to national economies. This approach is particularly notable in English-speaking countries such as the U.K., the U.S., Australia and Canada.

Canada’s 2013 Global Markets Action Plan [2], for instance, addressed international education as a priority sector in the nation’s effort to gain a competitive trade advantage “by sharpening … trade policy tools, putting boots on the ground, and promoting business-to-business links with partners globally.” “International education delivered nearly $20 billion to the Australian economy in 2015,” announced Australia’s minister for tourism and international education [3] in February. Education is now the nation’s “third largest export, following coal and iron ore.” [4] In the U.S., the Open Doors [5] report, published by the Institute of International Education and the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, closely tracks the nation’s competitive position in the international education marketplace. Traditional sending countries such as China [6], India [7], South Korea [8], and Russia [9] are also trying to get a piece of the incoming cake.

Amid this scrum, it’s worth stepping back to ask some baseline questions:

- What are the academic, civic, and ethical stakes of this approach?

- What is the human cost of the current, market-driven mindset to international recruitment?

- How can institutions responsibly recruit – and manage – the international student populations that they increasingly depend on to offset new (and often profound) budgetary challenges [10] affecting the entire sector?

Academic, civic, and ethical stakes

“The quest for cash has the potential to chip away, slowly and irreversibly, at higher education’s quality and the foundation of its public role,” Lara Couturier [12] wrote in a prescient 2002 article for International Higher Education [13]. Couturier was writing about the perils of a market-based approach to education in the U.S. context only, but her 14-year-old statement holds true in today’s international markets.

Indeed, in a recent piece for University World News [14], Gary Rhoades, head of educational policy studies and practice at the University of Arizona’s Center for the Study of Higher Education [15], speaks to exactly this point. Rhoades compares and contrasts the approach to international students among six institutions in three countries. The research he describes showed that four institutions in the U.S. and U.K. treat international students primarily as a source of revenue. This agenda, he argues, skews their recruitment efforts toward children of the new global elite – in particular from China and India. It also entails an academic cost.

“In privileging students who are able to pay to play,” he writes, “universities [in the U.S. and U.K.] are also privileging particular fields of study” that are “studied by students in the dominant international student markets of China and India – business and science, technology, engineering and mathematics, or STEM, fields.” The tradeoff, he warns, is “the educational balance that is so important to educational quality.”

Institutions in South Africa, meanwhile, evidence a clear “orientation to regional student markets,” and to both South Africa and the African continent “as an intellectual hub and as public cause.” Rhoades correctly notes that American and British universities have, by contrast, turned away from their public purpose. Granted that the U.S. and U.K. are far from alone in their increased focus on students as a commodity – in the last decade, for instance, Canada, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and recently Finland have all started to introduce full cost fees for international students – the approach raises a number of issues that are troubling at a systemic level.

It also extracts a high, non-financial toll on those at the heart of the educational enterprise: students.

Focus on students

As an increasing number of universities succumb to the temptation of the easy money offered by international students, many turn to recruiters and agents, some of whom are disreputable. Such middlemen have no interest in shepherding talented students to the right university for their skills and needs.

Illustrative of this trend is a recent New York Times article, “Recruiting Students Overseas to Fill Seats, Not to Meet Standards.” [16] The article highlights Western Kentucky University, which contracted an agency, Global Tree Overseas Education Consultants, to recruit students in India at a 15 percent fee per student. In its ad, Global Tree offers students some enticing carrots: an I-20 in one week, an offer in one day, no application fee, and last but not least ‘No WES Evaluation’.

Such tactics often snare internationals students who lack the language and academic skills they need to succeed, raising concerns on a campus that is only belatedly considering how best to support them. “It is ethically wrong to bring students to the university and let them believe they can be successful when we have nothing in place to make sure they’re successful,” the Western Kentucky’s student association president told the Times.

The road ahead

Where does this leave higher education institutions struggling to address profound budget shortfalls? There is nothing wrong with international student recruitment as such, but short term economic gain should not lead the process. Understanding the trends and context behind international student mobility – as well as the costs of unbalanced or expediency driven-recruitment efforts – is essential for universities operating in the international arena. In the end, the priorities must be the best interests of the students, the quality of education, and a commitment to the public good. Any other approach is neither sustainable and nor wise.

Hans de Wit is director of the Center for International Higher Education (CIHE) at Boston College. In June, CIHE and WES are partnering to provide an interactive seminar for higher education professionals who lead international operations and recruitment services at their institutions: The Changing Landscape of Global Higher Education and International Student Mobility. Learn more [17].