Paul Schulmann, Senior Research Associate, WES

“Internationalization” is, in the higher education context, too often a catchphrase for one simple goal: enrolling more international students – especially those able to pay full tuition fees, whether on their own or through government scholarships. But any robust internationalization strategy [1] has to address multiple facets, one of which should be the development of an inclusive and meaningful study abroad program. On this front, U.S. progress is uncertain, with the gross number of enrollments rising as the duration of time abroad drops. This situation entails challenges and opportunities across a number of fronts, from providing equitable access to all students, to ensuring benefits regardless of program duration, to optimizing recruitment and partnership opportunities for institutions.

This article examines current trends in study abroad, outlines how study abroad benefits both students and institutions, and provides recommendations about how institutions can more effectively implement study abroad programs that serve students and administrators’ goals.

Study Abroad Trends: Growing Popularity, Declining Duration

Last year U.S. higher education institutions (HEIs) sent fewer than 10 percent of their own students abroad during the course of their studies. Participation rates have crept up in recent years. At the same time program duration has declined.

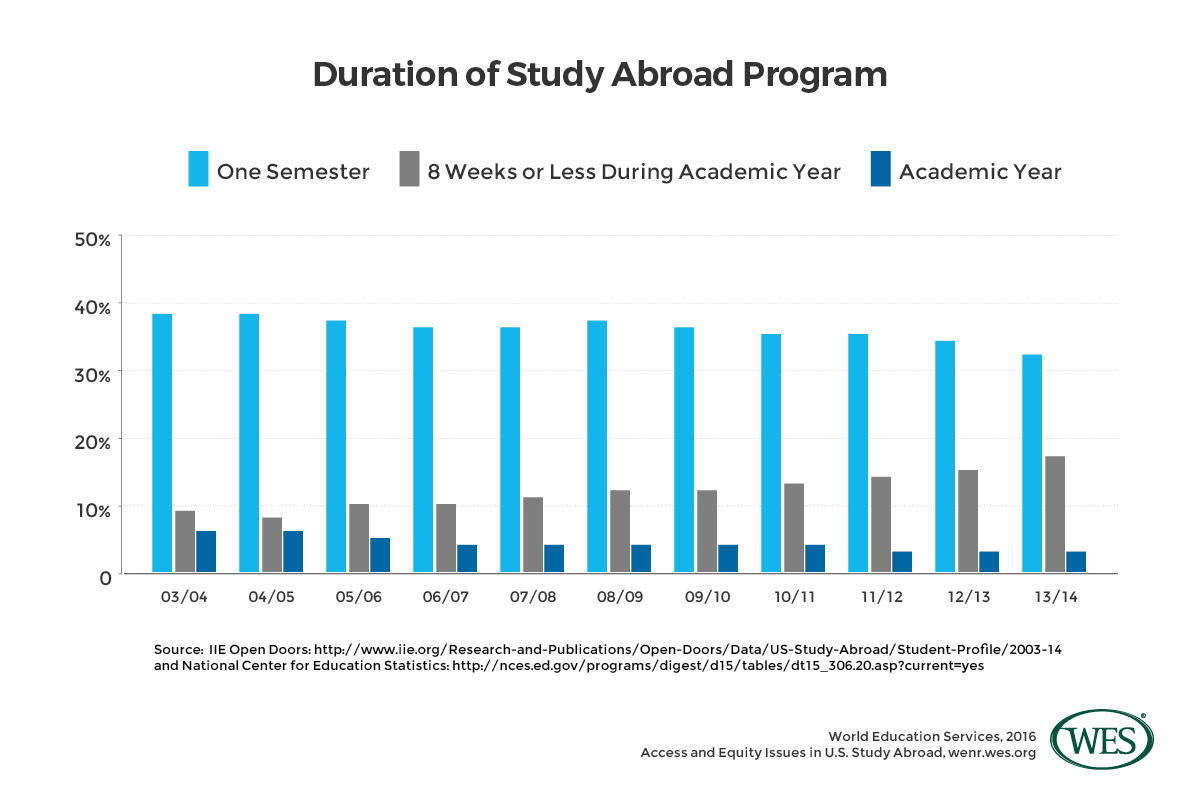

For the 2013/2014 academic year, the total number of U.S. students studying abroad reached a record 304,467 [2], a 5.2 percent increase from the previous year and a 59 percent increase from 2003/2004, according to the Institute for International Education (IIE). Over the same ten year period:

- The proportion of students participating in year-long programs fell by half. Today, only three percent of all study-abroad students participate in such long-term programs.

- The proportion of students participating in semester-long programs fell by six percent.

- The number of students participating in programs of eight weeks or less has almost doubled from nine to 17 percent. (See figure below.)

Given the fact that the most significant benefits of study abroad, at least as quantified by research accrue based on length of time abroad, this latter trend is one that institutions should monitor and seek to redress.

Who Gets to Go?

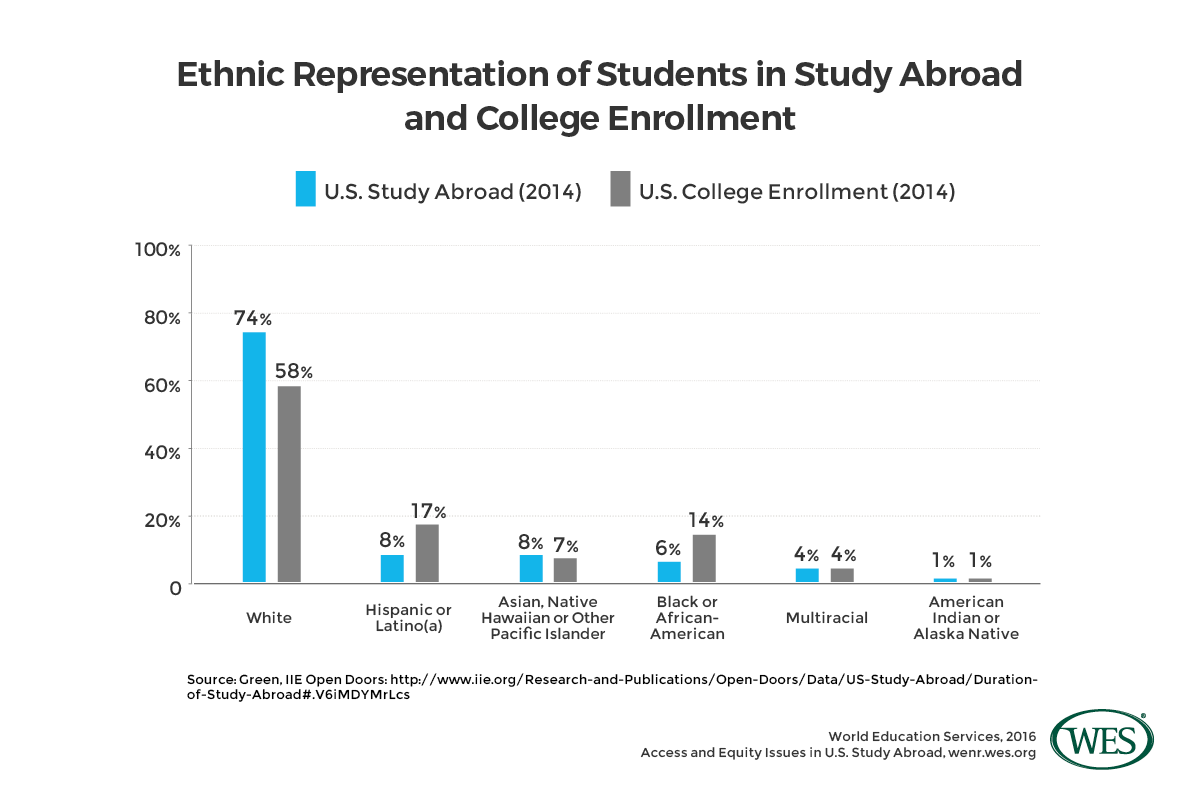

One of the more troubling aspects of study abroad initiatives is the ongoing disparity in the ethnic makeup of participants: Caucasian students comprise almost 75 percent of U.S. study abroad students, despite the fact that they account for only 58 percent of U.S. higher education enrollments overall. By contrast, Hispanic and African American students make up only eight and six percent of study abroad participants respectively – despite the fact that they comprise 17 percent and 14 percent of college enrollments nationwide. (See Figure Below.)

Given the real benefits conveyed by study abroad in terms of graduation, social capital, and more, these disparities in participation have long-term – and unacceptable – implications.

The Benefits of Study Abroad for Students

A body of research supports the idea that study abroad has benefits for students. These include:

- Personal and academic development: The benefits of study abroad participation increase with the duration of the experience. A 2004 study, which surveyed students as long as 50 years past their study abroad experiences, found multiple student-level benefits – in terms of both personal and academic development – associated with longer programs. Compared to single-term study abroad program participants, full-year participants were more likely to change or expand their majors, and twice as likely to pursue PhDs, and to develop and maintain life-long friendships with nationals from the host country.1 [5]

- College completion & reduced time to degree: Case studies [6] collected by the Center for Global Education at California State University, Dominguez Hills have shown that participation in study abroad increases college graduation rates. Research conducted at Indiana University in 2009 found that 95.3 percent of students who studied abroad graduated within six years as compared to 68.5 percent of students who did not. A system-wide study for the University of Georgia found that students of color who studied abroad had a 17.9 percent higher 4-year graduation rate and that African-American students who studied abroad had a 31.2 percent higher four-year graduation rate. In fact, the study showed that study abroad participation led to near parity in white and African-American student graduation rates at 84.4 percent and 88.6 percent for participants.

- Increased global awareness: A study by scholars at Kennesaw State University [7] found that even a two-week study tour had a measurable impact on participants’ “understanding of Mexico as a commercial power and of Mexicans as diverse, rather than homogeneous, ” Over the course of the two weeks participants also “came to note that Mexicans as a population were not really that different from the ‘folks back home.’” Importantly, the program had specific and measurable objectives and included presentations conducted by government officials and executives from Mexican industry, cultural excursions to museums, archaeological and historical sites, and local markets.2 [5]

Do Short Term Programs Have a Place in Comprehensive Internationalization?

The overall increase in study abroad participation may well be attributable to the availability of shorter programs, as campuses move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach to one that provides opportunities through flexibility. Short-term programs cost less, and so may be accessible to more students. That said, at least one study on short-term study abroad programs found that left to their own devices, students can make shallow observations and interpretations of potentially meaningful cultural interactions if the program is not mediated through expert guidance. The net of this study and the Kennesaw State University study which found that a two-week tour had a measurable impact on participants’ understanding of key aspects of Mexico’s economy and culture indicate that short-term programs can have a meaningful impact if they are designed well, and a negligible impact if conducted haphazardly.

The Benefits of Study Abroad for Institutions

“Comprehensive internationalization” has become an increasingly important part of the strategic agenda for higher education institutions. Although study abroad programs represent only one component of this agenda, they are important from the perspective of institutional goals such as student recruitment, retention and completion goals, access, and equity.

- Recruitment: The 2004 study cited above found that longer duration programs had an important impact on institutions’ efforts to recruit domestically. Twenty-seven percent of students who participated in full-year programs said that the ability to study abroad was a criterion in their decision to choose an undergraduate institution. The figure shrank to 22 percent among students enrolled in semester programs, and 10 percent among those enrolled in summer programs. An American Council on Education report, A Report on Two National Surveys About International Education [8], found that among college-bound high school students, 86 percent said they planned to participate in international courses or programs and almost 50 percent expressed an interest in study abroad. The report’s authors laid out the case for the competitive advantages conferred by study abroad programs in no uncertain terms: “High school students … will increasingly arrive at colleges and universities expecting international training to be available,” noted the authors. “In this climate, institutions will need to meet their demands, on campus and abroad, or risk losing students to colleges and universities that do. It is clear that students, parents, and the public are looking to higher education to provide strong international … programs.”

- Progress against overall retention as well as academic and completion goals: Study abroad programs could serve as a potent force for meeting retention objectives and improving educational attainment outcomes. In a 2012 strategic initiatives proposal [9], the University of Vermont provost’s office noted that study abroad has benefits such as “increased retention and graduation rates, and correlation to overall academic performance.”

- Improving time to graduation and graduation rates of minorities: A system-wide study for the University of Georgia found that students of color who studied abroad had a 17.9 percent higher 4-year graduation rate than those who did not, and that African-American students who studied abroad had a 31.2 percent higher four-year graduation rate. In fact, researchers found that study abroad participation led to near parity in white and African-American student graduation rates (84.4 percent and 88.6 percent.) If such results could be extrapolated more broadly, the impact would be a potent force for meeting retention objectives and improving the educational attainment outcomes of minority students. Consider: From 1996 to 2012, college participation rates for black and Hispanic students increased dramatically, growing 240 percent and 72 percent respectively. However, analysis from PEW Research [10] indicates that retention and graduation rates remain stubbornly low as compared to their overall representation as a fraction of the broader U.S. population.

The Takeaway

In an increasingly globalized and competitive world, it’s important to recognize that a quality education must impart students with diverse perspectives and nuanced views. This education should transcend the boundaries of the classroom, the campus, and the country. Given the wide-reaching benefits of study abroad and its crucial role in comprehensively internationalizing HEIs, institutions should make concerted efforts to increase participation, design short-term programs based on good practices, encourage longer stays, and ensure that study abroad cohorts reflect the diversity of the institution.

Recommendations

Ideally, institutions should encourage and enable greater participation in long-term study abroad programs, while also offering high-quality short-term programs that provide meaningful experiences for participants. One way to encourage longer-term programs is to ensure credit mobility by partnering with diverse institutions that can provide high-quality courses for students in a range of disciplines. It’s also important to educate prospective study abroad participants about how study abroad affects their ability to complete their degrees in a timely manner, which will encourage more students to consider long-term programs as a realistic and beneficial option.

Increasing the participation of underrepresented minorities should also be a moral and strategic imperative for colleges and universities. Initiatives such as Diversity Abroad [11], an international organization that seeks to connect diverse students, recent graduates, and young professionals with international study, internship, teaching, volunteer, degree, and job opportunities, can help encourage underrepresented minorities to participate, but individual institutions should likewise find pragmatic ways to diversify their study abroad cohort and increase the participation of underrepresented students. One way is to actively market study abroad programs to groups of students who participate in lower numbers. Institutions can partner with clubs on campus, or coordinate their efforts with campus organizations that support minority students.

Moreover, institutions with available funding should consider increasing study abroad scholarships for underrepresented students. Offering study abroad scholarships to first-generation students is one way to increase minority student participation, and has been implemented by Butler University through its First Generation College Student Program [12]. Providing study abroad scholarships to students on Pell Grants is another way to increase the participation of minority students, who disproportionately [13] receive such grants. This approach is practiced by the University of San Diego through its retention promoting Second Year Experience Abroad [14] program.

Lastly, institutions should strive to increase the global reach of their study abroad programs, by developing meaningful partnerships with more institutions outside of Europe. Such partnerships will not only help to address the broader goals of comprehensive internationalization, but would likely further increase minority representation. In one 1996 study, African-American and Hispanic students were the most likely to report interest in studying abroad in a place that reflects their ethnic heritage.3 [15] Currently, 53 percent of study abroad participants go to Europe, which is home to approximately 11 percent of the world’s population.

1. [16] Dwyer, M. M. (2004). More Is Better: The Impact of Study Abroad Program Duration. Frontiers: The interdisciplinary journal of study abroad, 10, 151-163

2. [17] Carley, S. & Tudor, K. (2006) Assessing the Impact of Short-Term Study Abroad Carley Kennesaw State University

3. [18] Carroll, A.V. (1996). The participation of historically underrepresented students in study abroad programs: An assessment of interest and perception of barriers. Unpublished master’s thesis. Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State University.