Paul Schulmann, Senior Research Associate, WES

With a new administration coming into office in the U.S., it’s worth pondering Washington’s role in promoting inbound mobility among international students. The U.S. lacks a coherent national policy framework designed to attract international students. This stands in marked contrast to other countries that compete with the U.S. for international enrollments, notably Australia and Canada.

The U.S. government does, however, support a patchwork of programs, initiatives, and policies designed to increase international student mobility. In an increasingly competitive and globalized higher education marketplace, it behooves U.S. institutions to understand and know how to navigate the available options. (For a comparative look at policy approaches to international student mobility in the U.S., Canada, and Australia, check out this month’s companion piece [1] on LinkedIn.)

The Diplomatic Approach: International Education as Human Capital Development

Australia, Canada, and other countries often view the potential benefits of international student mobility primarily in economic terms: How much money do international students bring in now, and how do they benefit the economy and workforce today? How will they offset the economic impact of an aging domestic population? And while the U.S. government is certainly aware of – and actively focused on – the short and long-term economic impacts of inbound mobility, its approach is often framed through the lens of diplomacy.

U.S. programs that support inbound international student mobility thus often fall under the purview of the Department of State, specifically its Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA). These include well-known initiatives like Education USA and the Fulbright programs (detailed below). They also include a number of programs that focus on human capital development and capacity building for developing countries:

- The Global Undergraduate Exchange Program [2] provides scholarships for one semester to one academic year for international exchanges for students from participating countries. Studies are complemented with community service, professional development, and cultural enrichment activities.

- At the community college level, the Community College Initiative (CCI) Program [3] allows students from 21 countries to study for one academic year in order to obtain certificates in their field of study. The program focuses on improving students’ technical skills, leadership qualities, and English proficiency, and also gives participants the opportunity to participate in professional internships, service learning and community engagement.

- The ECA also supports efforts that increase international student mobility to the U.S. at the country-specific or regional level. The Tunisia Community College Scholarship Program (TCCSP) [4], for example, offers full, one-year scholarships to Tunisian students enrolled in technical or vocational training, providing them with skills applicable to the Tunisian economy.

- Another recently enacted initiative is the 100,000 Strong in Americas [5] , a collaborative endeavor between the Department of State, Partners of the Americas, and NAFSA. 100,000 Strong aims to increase student mobility within and to the Western Hemisphere.

- Short-term programs such as the Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiatives [6] also focus on capacity building abroad, and bring students to university campuses across the United States – albeit for-a very limited time and in limited numbers.

EducationUSA & Fulbright

One of the largest programs state-department-supported international education programs is EducationUSA [7], an educational advising network with approximatively 400 centers in 170 countries. The initiative provides professional advice on study and research opportunities to prospective international students. EducationUSA also collaborates with higher education institutions on recruiting international students and assists the institutions in understanding international higher education systems and trends. The program holds approximately 30 education fairs and one to two regional forums annually. EducationUSA also produces the Global Guide [8], which assists international recruitment by providing pertinent information about various regions and countries, and funds the Open Doors [9] report, an invaluable resource for international student recruiters, decision-makers, and researchers tracking international higher education trends.

The state department also supports multiple Fulbright Programs [10]. The 70-year old Fulbright initiative is active in more than 170 countries. It seeks to facilitate the mobility of students and scholars into and out of the U.S. In terms of inbound foreign students, the main program is the Fulbright Foreign Student Program [11], which provides funding for prospective international graduate students, young professionals, or artists to study or research for one year or longer at qualifying institutions.

The Economic Imperative: The Long-Term Payoff of Inbound Student Mobility

In 2015, international students contributed more than more than $30.5 [12] billion dollars to the U.S. economy according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. With 72 percent [13] of these students’ funding (tuition plus their economic contributions to the broader economy) originating outside of the U.S., they bring an enormous source of revenue into the country. While these direct economic contributions are significant, there are also major advantages to using international education as an avenue for increasing skilled immigration to the U.S. These include immediate benefits to both students and American companies hoping to acquire top, entry-level STEM talent, as well as significant long-term economic returns.

Visa policy, which sits under the purview of Immigration & Customs Enforcement, is the main instrument under consideration in terms of workforce and employment considerations; the two types of visas that are of particular pertinence are the F1 visa (or OPT visa) and the H1B visa.

- The F1 Optional Practical Training visa (OPT) is designed as a foreign worker training program that allows international students to remain in the U.S. after graduation in order to work in the fields in which they trained. In early 2016, STEM students in specific fields [14] saw a significant extension in the length of time they were permitted to stay in the U.S. under OPT. An earlier iteration of OPT, STEM students were allowed to work in the U.S. for 12 months after graduation, with a possible extension of 17 months. The new regulations stretch the extension to 24 months, meaning that graduates can stay in the U.S. and work for up three years total. (The Washington Alliance of Technology Workers has sought to see the extension overturned, and in June 2016 filed a lawsuit [15] with the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to contest it – its second effort to use the courts to overturn the extension.)

- H1-B visas are temporary, three-year work authorization permits for employees with employer sponsorship. They are renewable for a three-year extension. Students cannot apply for H1-B visas; rather, students must find jobs with employers who will apply on their behalf.

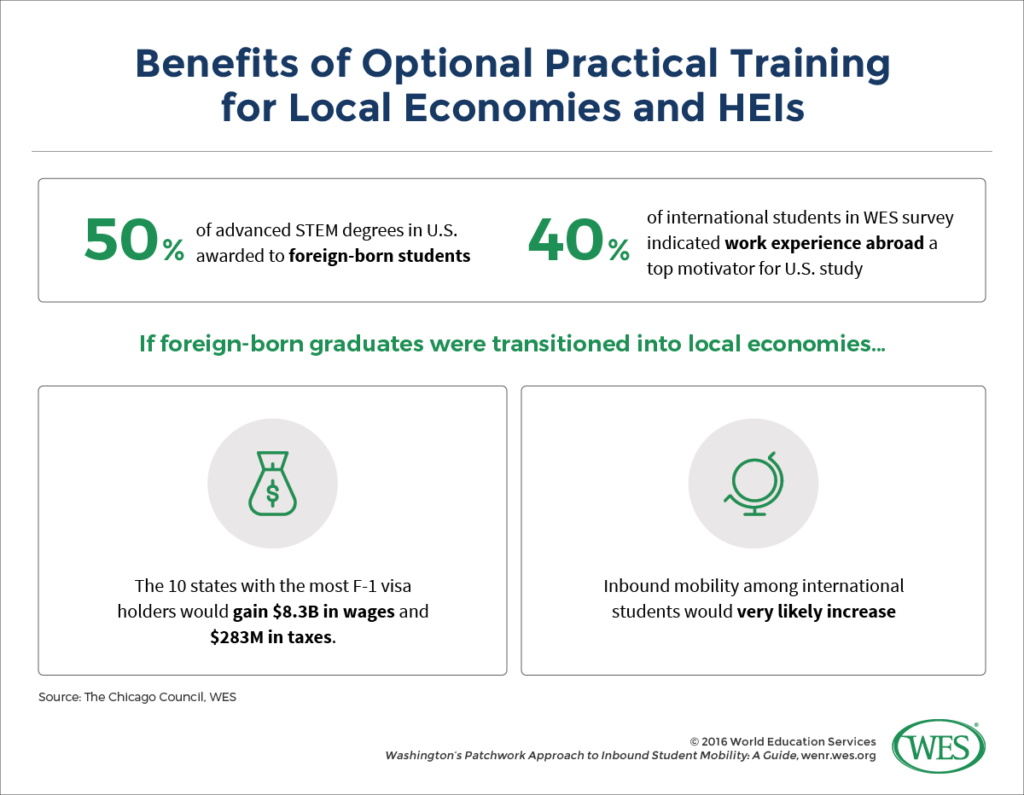

Recent research [16] by WES reaffirmed the importance of career advancement as a primary reason that international students enroll in U.S. higher education institutions. Forty percent of the more than 4,600 international students surveyed indicated that the “opportunity to gain work experience outside home country” was a top motivator for studying in the U.S. (This reason was second only to “better education outside my home country.”)

Given international students’ career focus, the OPT extension may improve inbound mobility among international students.Research from the Chicago Council on Global Affairs [17] bears this out. “The availability of OPT—especially extended versions of OPT for STEM students—shows promise in boosting college-to-workforce transition rates for students on F-1 visas,” economist Giovanni Peri wrote in a paper examining the economic impact of helping foreign-born students obtain long-term employment in the cities and states where they studied. “Comparing aggregate transition rates for two cohorts of F-1 visa holders—those who graduated before the 2008 extension compared to those who graduated after—suggests that OPT increased workforce transition rates between 7 and 25 percentage points.”

Visa Policy & Student Retention: A Missed Opportunity

Current visa policies considerably limit both the career options of international graduates of U.S. institutions and the economic benefits of educating international students, especially the significant number pursuing STEM degrees. Economist Giovanni Peri has found that, “while programs like Optional Practical Training (OPT) … allow [International] students to temporarily remain in the United States… new calculations suggest that the state and metropolitan areas where they study are largely unable to retain them in the five years after graduation.”

The costs, says Peri, are largely felt within the states and communities where those students earn those degrees. “The 10 states with the largest populations of F-1 students lost an average of nearly 3 percent of their potential college-educated employees,” he noted in a 2016 paper [17]. “The economic impact of this lost human capital is perhaps best understood in terms of lost wages and taxes in state and local economies. The 10 states with the most F-1 visa holders stand to gain nearly $8.3 billion in wages and $283 million in state taxes.

Inflexible work visa policies leave international graduates with few work options in the U.S. beyond the term of the OPT extension. In a 2009 study [19] for the Technology Policy Institute, senior fellow Arlene Holen estimated that, without H1B visa constraints, the U.S. would have retained an additional 182,000 foreign STEM graduates between existed 2003 and 2007. These graduates would have contributed USD $14 billion to the economy in 2008, including USD $2.7 to $3.6 billion in tax revenue.

The Campus View: International Students as an Academic Asset

From the perspective of the institutional bottom line, the appeal of a full-fee paying international student is undeniable [20]. However, the campuswide impact that well-selected, and well-supported international students can have is far richer, deeper, and more critical. This is particularly true in terms of academic benefits for their domestic peers. One 2013 study [21] published in The Journal of International Students, for instance, found that domestic students who interacted substantially with international students reported increased intellectual development across broad range of measures, including:

- Reading or speaking a foreign language

- Relating well to people of different races, nations, or religions

- Acquiring new skills and knowledge independently

- Formulating creative or original ideas or solutions

- Synthesizing and integrating ideas and information

- Achieving quantitative abilities

- Understanding the role of science and technology in society

- Gaining in-depth knowledge of a field

Practical Tips: Increasing International Enrollments, and Pressuring Government to Increase Inbound Student Mobility Efforts

Economic and academic benefits notwithstanding, the United States is unlikely to establish a national framework for international education anytime soon. As international education expert Robin Matross Helms noted in a 2015 report for the American Council on Education [22], the U.S. lacks “a ministry of education or other agency that holds overall responsibility for higher education nationwide.” It is thus up to institutions to navigate and leverage the patchwork of programs and public policies available to help increase international student numbers. In concrete terms, this means a few things. HEIs should:

- Focus on developing a strategic international enrollment management plan that:

- Leverages data from the Institute of International Education’s Open Doors [9] report

- Measures and weighs the returns on investment (ROI) [23] of various recruitment tactics and efforts

- Understand the full range of government-supported programs available to help drive in-bound recruitment, and leverage available resources to boost enrollment numbers, by, for instance, participating in EducationUSA [7]

- Bring the importance of international students to a greater level of public awareness as part of a broader effort to compel policymakers and politicians [24] to:

- Develop policies that aid in inbound student mobility

- Better resource programs now in existence

- Ensure that prospective international students understand how recent OPT extensions can help them to meet their long-term professional development goals.. [25]

While U.S. government efforts to support inbound student mobility are far from unified, they do exist. Learning how to navigate them offers institutions a leg-up in the competitive global higher education marketplace.