Alejandro Ortiz, Senior Research Associate, and Ashley Craddock, Editor

Despite hosting a record number [2] of international students in the 2015/16 academic year, the U.S. has seen its overall share of the international student market [3] decline in recent years. Recent events are likely to shake student confidence and further erode that share. A January 27 executive order [4] affecting citizens of seven majority-Muslim countries has thrown colleges, universities, students, and others into confusion [5]. Leaked drafts [6] of executive orders that would shrink the professional opportunities available to international students have amplified those concerns.

The January 27 order bars citizens of Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen from entering the U.S. Most of these countries (with the exception of Iran) send relatively few students to the U.S. Commentators nonetheless predict that we may witness a “domino effect” [7] that dampens higher education enrollments among students from across the Arab region and beyond. Challenges to the executive order are now working their way through the courts; but both the immediate and the potential for lasting impacts on students and long-term are real.

Even prior to the travel ban, however, student mobility patterns in and from the region had begun to change, especially as intraregional academic mobility has risen. To help elucidate these broader patterns and their potential implications for institutions in the United States, this article offers a brief overview of student mobility trends in five countries that are particularly dynamic in terms of international student mobility: Egypt, Iran, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Increased Internationalization: A 15-Year Trend

In their 2015 book, Higher Education Revolutions in the Gulf: Globalization and Institutional Viability [8], authors Fatima Badry and John Willoughby argue that countries in the Gulf Region have, in the past 15 years, adopted the norms of Western-style higher education at an unprecedented level. In the same period, the region has seen new student mobility patterns. Specifically, the authors note, “the increasing numbers of non-national students attending universities and colleges in the region [represents] a significant change [and]…. a decision by authorities to create colleges and universities that cater to” international students. https://books.google.com/books?id=zi-vCgAAQBAJ&pg [9]

Evidence of this shift, they argue, is everywhere. In their discussion of the Arab Gulf states, including Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and UAE, Badry and Willoughby cite several examples of special note:

- Policy shifts among governments around the region to promote “Western-oriented educational reforms.”

- “[T]he emergence of new academic centers [that inevitably create] a new hierarchy of educational institutions and a decline in the prestige and influence of indigenous institutions.”

- Efforts to place in the global rankings race. This phenomenon spurs non-Western universities, seeking to be perceived as “comparable to their Western counterparts” to, as the authors note, “willingly subject themselves to Western assessment bodies” and “do all it takes” to win recognition.

- “The elite branch campus phenomenon,” which took off in Qatar in the late 1990s, and has since been replicated throughout the region. The phenomenon entails the effort by governments to attract satellite campuses from top institutions in the West. Examples of U.S. branch campuses in the region include Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar, Texas A&M University at Qatar, Northwestern University in Qatar, New York University Abu Dhabi, Harvard Medical School Dubai Center, Michigan State University Dubai, and New York Institute of Technology in Bahrain. Institutions in the U.K. have also opened a number of branch campuses in Arab countries.

- A move towards “common language, curricula and academics,” which, the authors argue, are an artifact of “joint degree programs, …“global network branch campuses or the drive to obtain Western accreditation.” Increasingly, the language of instruction at many institutions seeking to internationalize is English.

Egypt: Rising Ambitions as a Regional Destination

Egypt sent just 3,442 students to the U.S. in 2015/16. Although not a major contributor of students, it has long been a regional hub for higher education, and despite quality challenges and political strife, is seeking to expand its regional reach. It merits attention from observers interested in higher education trends in the Middle East for several reasons.

- Egypt is already a regional education destination. According to the most recent data available from UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics [10] (UIS), Egypt hosts some 47,815 international students. Cairo University is the biggest draw [11], enrolling an estimated 10,000 foreign students each year. Benha University [12] comes in second, with more than 6,600 foreign students enrolled annually. Leading places of origin for international students in Egypt include Malaysia, Kuwait, and Indonesia. [2]Although all three countries were top 25 contributors of international students to the U.S. in 2015/16, it’s debatable whether or not Egyptian and U.S. higher education institutions are actually in competition for the same pool of students. It may be that Egyptian institutions attract students who are primarily interested in Islamic studies (a strong feature of many Egyptian institutions) or who are seeking to enroll in institutions in a culture similar to those of their countries of origin.

- Egypt sends a substantial number of students abroad, but relatively few go to the U.S. Substantial numbers of Egyptian students study at tertiary institutions in countries that are relatively close to home. Of almost 25,000 globally mobile Egyptian students counted in the most recent UIS figures [10], some 9,260 enrolled in institutions in the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. This is more than three times the number who, according to UIS data, enrolled at U.S. institutions.[3]UIS data is somewhat dated. The number reported by UIS in January 2017 was 2,928; the most recent number available from the Institute of International Education’s Open Doors 2016 report is 3,442, which represents a 15.7% increase over the previous year’s 2,974 students.

- Egypt is home to a large number of regionally ranked institutions. While rankings are notoriously unreliable as a true measure of quality, they are likely a factor in the country’s ability to draw enrollments from other countries in the region. According to QS University Rankings: Arab Region 2016 [13], Egypt was second only to Saudi Arabia in terms of regional reputation for quality, with 15 institutions in the top 100.Best Arab Region Universities Rankings [14], by contrast, puts Egypt as the top-performing country, with 25 universities in the overall rankings out of 124.)

- Egypt is actively investing in the effort to transform itself into a regional hub for higher education. In January 2015, the country’s Supreme Council of Universities announced a plan [15] to quadruple international enrollment to 200,000 within three years [16]. While funding figures for the effort were not made publicly available, one widely reported estimate put available funding at “a conservative figure of USD $50m guaranteed [16]” for 2015. Key recruitment areas include Africa and the Arab region, both regions of interest to the United States. Partnerships are one key to the effort, and in 2016, Times Higher Education reported that “universities in the UK and Egypt … signed 10 partnership agreements aimed at building scientific research and increasing opportunities for student and staff exchanges.” [17] Egypt was reportedly seeking to ink another 20 such partnership agreements with U.K. institutions over the next two years.

Ambitions aside, Egypt’s ability to draw significantly greater numbers of students from across the region may be unrealistic. Political conflict [18] as well as the capacity and the quality of the country’s higher education both pose barriers to the goal of increased foreign enrollments.Al-Fanar Media [11] reported that “Egyptian universities have begun the academic year with no new government-sponsored master’s degree and Ph.D. students from Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Qatar’s Ministry of Higher Education excluded Egyptian universities from its list of approved universities, meaning that even if a Qatari student attended an Egyptian university at his own expense, his degree would not be recognized at home.”

Iran: Growing Outbound Numbers

Iran in the World

In 2016, the removal of international nuclear sanctions [19] gave rise to widespread speculation that Iran would once again become a leader in international student mobility. At the time, U.S. colleges and universities were poised to be major beneficiaries of that outbound traffic. In 2011/2012, the number of Iranian students taking the GRE ran fourth behind the U.S., India, and China [20], indicating high interest among graduate students. (Iranian enrollments in the U.S. are primarily at the Master’s and PhD levels.) And in 2015/16, the numbers seemed genuinely promising. According to IIE’s Open Doors report, some 12,269 Iranian students enrolled in U.S. institutions last year, up 8.2 percent over the previous year. That was the 11th year of growth in a row, many with double digits, and made Iran the 11 [21]th [21] leading sender of students [21] to the States, a slot it occupied in 2014/15, as well.

Globally, Iranian outbound student mobility is on the rise. The most recent estimates from UIS include some 48,067 Iranian nationals studying abroad – a number that will surely increase given the end of nuclear sanctions. These students’ top five destinations are, in descending order, the United States, Turkey, Canada, Italy, and Germany. Going forward, that order will likely change in light of the fact that Iranians are a clear focus of President Donald Trump’s January 2017 executive order on immigration. [22] Many who might have opted to study in the U.S. will now be forced to go elsewhere.

NOTE: This issue of WENR focuses heavily on Iran, and includes articles that focus on Iranian students in the U.S. [23], a history of the impact of Iranian-U.S. enmity on Iranian student mobility to the United States [24], and on the Iranian education system [25].

The World in Iran

According to the latest data from UIS, Iran hosts some 13,767 students from abroad; in 2014, the total volume of inbound students in Iran was only one-sixth of those received by institutions in Saudi Arabia. More than 82 percent of international students in Iran come from Afghanistan; 8.7 percent come from Iraq; and another 6 percent come from Syria, Lebanon, and Pakistan, combined. After that, countries send students to Iran by the dozens or less.

The country is unlikely to become a top destination for Arab countries – including those which, like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, are significant countries of origin for international students on U.S. campuses. Language is one barrier. Politics are another. As Rasha Faek noted in a recent piece in Al-Fanar Media [19], long-standing political tensions render that possibility a non-starter. “Iran and its Arab neighbors maintained a wary relationship throughout the 20th century,” Faek wrote. “Relations deteriorated rapidly after the Islamic Revolution in 1979, when Iran’s Shiite rule became stronger and the Iran/Iraq war broke out. Gulf countries have also accused Iran of spreading sectarianism in the region. Iran’s support of the rebel Houthis in Yemen has resulted in a proxy war with Saudi Arabia, and its support of Syria’s current government has also brought it into conflict with both international and regional powers.”

Kuwait: Lack of Capacity at Home = Increased Student Mobility

Kuwait was the 16th leading sender of students to the U.S. in 2015/16, with 9,772 Kuwaiti nationals on U.S. campuses. The number inbound Kuwaitis has increased dramatically over the last decades, rising by double digits [26]every year from 2007/08 to 2014/15. Kuwaiti student numbers took large leaps in both 2013/14 and 2014/15 – 37.4 percent and 42.5 percent respectively, growing from 5,115 to 7,228. In 2016, the year over year growth rate was 8.2 percent; this considerable drop still represented far greater growth than the 2.2 percent growth rate of Saudi enrollments.

These students are part of a broader outbound movement, attributable in part to government-funded scholarship programs [27]. More than 33,000 Kuwaitis [28] are estimated to be studying abroad around the world. Many do so courtesy of scholarship programs designed to relieve pressure on Kuwait’s own higher education sector. The University of Kuwait, the country’s lone public university, comes in # 24 in QS Arab University rankings [29]. However, it struggles to meet the needs of the 37,000 students enrolled there.

According to Newsweek Middle East [28], “the government provides full tuition for up to 6,000 Kuwaiti students annually to pursue their education abroad… [a]s a solution” to such shortfalls in capacity. The government also provides students with scholarships to study at the country’s nine private universities, which, as noted by Al-Fanar Media [30], educate half of the country’s university students.

Whether or not Kuwaiti students will continue to seek out U.S. institutions at the rate they have in the past is unclear for a couple of reasons. First is the potential domino effect of the January 2017 immigration order from the Trump administration. Kuwait is not named, but students may nevertheless be loathe to attend school in a country where they feel unwelcome.

Second is the regional context: Kuwaitis have good options closer to home. Per UIS data [10], the country already sends substantial numbers of students to Jordan [31], Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates – all of which are positioning themselves as regional tertiary education hubs, especially for students in other countries nearby. Given Kuwait’s oil-dependent economy and recent instability in the oil market [32] and U.S. policies that dampen student interest, continued expansion of Kuwaiti numbers on U.S. campuses cannot be taken for granted. But strong year-over-year growth in student numbers may be a sign that Kuwait may continue to be a relevant recruitment market for U.S. institutions.

Saudi Arabia: A Growing Education Destination; Slowing Outbound Rates

Saudi Arabia has been a significant country of origin for international students in the U.S. and other countries for more than a decade. UIS [10]’ most recent numbers show some 83,241 Saudi Arabian students enrolled in foreign institutions around the world. And, despite the shrinkage of a key government scholarship program that long-funded Saudi students’ at institutions around the globe, their numbers on U.S. campuses continued to grow, albeit at a far slower pace than in previous years.

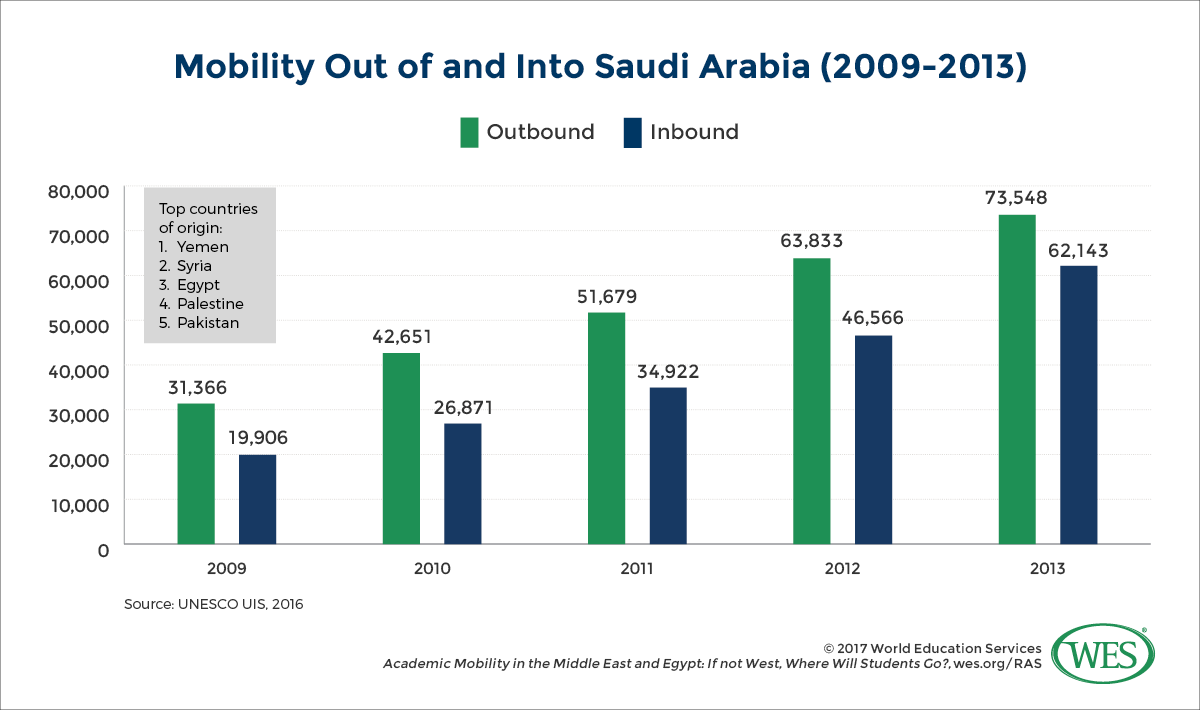

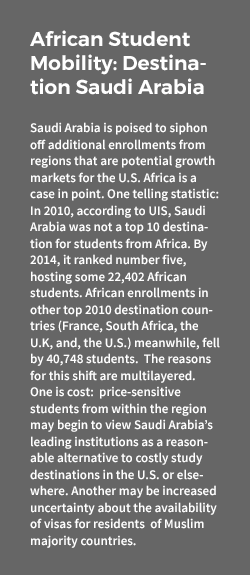

More recently, the country has emerged as a top regional hub for higher education – and one that shows significant ability to draw Middle Eastern students’ interest. The most recent UIS data show that the Kingdom is host to some 73,077 international students. According to WES analysis of this data, this makes Saudi Arabia the top host of international students within the region in 2014 (left chart in figure 1), attracting more than seven times as many international students as Qatar (another regional magnet [33] for international students). In particular, Saudi Arabia attracts significant intraregional mobility among students from Yemen, Syria, Egypt, Palestine, and Pakistan. It has also begun to attract a large number of students from Africa.

More recently, the country has emerged as a top regional hub for higher education – and one that shows significant ability to draw Middle Eastern students’ interest. The most recent UIS data show that the Kingdom is host to some 73,077 international students. According to WES analysis of this data, this makes Saudi Arabia the top host of international students within the region in 2014 (left chart in figure 1), attracting more than seven times as many international students as Qatar (another regional magnet [33] for international students). In particular, Saudi Arabia attracts significant intraregional mobility among students from Yemen, Syria, Egypt, Palestine, and Pakistan. It has also begun to attract a large number of students from Africa.

The reasons behind its regional pull success are likely several:

- Rankings: Saudi Arabia is home to a number of highly ranked institutions, especially by comparison to the regional competition. QS ranks 19 of the country’s universities as among the Arab region’s top 100 [34].

- An explicit focus on internationalization through partnerships and scholarships: Saudi Arabian institutions have actively embraced of internationalization strategies. Universities in Saudi Arabia seek to promote international enrollments through various funding incentives, state-of-the-art facilities, and research collaborations with foreign universities [35]. The Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission [36] actively promotes scholarships for international students, and, as of this writing, lists some 23 government universities with scholarships available to foreign nationals.

- Costs: The appeal for many students from within the region may be pragmatic as well: The cost of living in Saudi Arabia is relatively affordable by the standards of many international students. WES research shows that such costs matter to – and are a significant pain point for – Middle Eastern students in the United States. [37]

The country’s rising status as a regional higher education hub has important implications to U.S. higher education institutions. To some extent, it may reduce Saudi students’ interest in U.S. education – a potential additional hit to already lowered enrollments in the U.S. IIE’s 2016 Open Doors report notes that Saudi Arabia “replaced South Korea as the third leading place of origin for students coming to the United States after being fourth for 5 years in a row.” In 2015/16, the Kingdom sent some 61,287 students to the U.S., up from 59,945 the year prior.

Despite higher enrollment numbers, however, last year saw the lowest growth rate of U.S.-enrolled Saudi students enrolled in a decade [38]. Unprecedented economic turmoil in Saudi Arabia was the root cause of this softened demand. Facing a severe and ongoing downturn in oil prices [39], Saudi Arabia implemented widespread budget cuts [40] in 2016; these, in turn, led to restrictions on the multibillion-dollar King Abdullah Scholarship Program (KASP), which, in its decade-long existence, supported more than 200,000 Saudi students [41] enrolled at institutions around the globe.

NOTE: In response to restrictions on KASP, the U.S. Department of Commerce predicted a downturn in Saudi student enrollments from 2016 through 2020 [42]. Although 2015/16 enrollments outperformed the Commerce Department’s predictions, broader expectation of a downward trend are likely realistic. Decreased government funding international education may lead Saudi students to enroll in institutions closer to home. That said, the Saudi government is expected to increase its spending [43] in 2017 in order to stimulate internal growth; the implications for KASP are unclear.

United Arab Emirates: The #3 Destination for Arab Students Abroad

United Arab Emirates (UAE) is number 38 on IIE’s 2015/16 list of countries of origin for international students in the U.S. – the 2,920 UAE students on U.S. campuses are a fraction of those sent by the bigger regional senders on the list. But the country is a major recipient of international students. It hosts some 73,445 students per UIS’ most recent data, and is second only to Saudi Arabia both as a host to and a generator of internationally mobile students.

Perhaps even more interesting is the country’s position within the region. According to a 2015 article by British education and rankings experts QS [45], “the UAE (specifically Dubai) overtook the U.K. to become the third-leading destination for Arab students abroad, behind France and the U.S.” Collectively, the top ten Middle Eastern senders, which include Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Iran, send some 40,632 students to the UAE. The country also attracts significant numbers of students from Lebanon, Nigeria, and Kuwait.

The U.A.E.’s rising status as a higher education destination is due in no small part to government policies that favor internationalization of the sector [46], and to substantial government spending [47]. Rankings also play a role. In 2016, QS University Rankings: Arab Region, QS said [13] that “the United Arab Emirates is on a par with Saudi Arabia” in the context of top 50 institutions in the region. With an increasing budget allocated to higher education, UAE has also become an ideal location for institutions from around the world that are seeking to expand their global footprints. According to the Observatory on Borderless Education [48], UAE is the 2nd leading country for international branch campuses [49] behind China.

Quality Challenges

For all its prominence as a higher education hub, questions about the quality of higher education in the UAE are widespread. One 2016 paper [50] on the quality of the country’s higher education sector cites challenges with research capability, the quality of instruction, and student recruitment. Rapid expansion of the private sector poses a major challenge, noted the researchers. The UAE has only three public universities; the first is only 40 years old. An additional 75 are private higher education institutions that are “mostly profit-driven,” according to the researchers, who note that a grade – rather than skills – focused culture hurts the sector.

In the face of rapid growth, the UAE’s Commission for Academic Accreditation has insufficient capacity [51] to review the institutions under its purview. The Emirati government has nonetheless sought to address challenges. In the fall of 2016, the UAE’s Ministry of Education published a list of licensed higher education institutions and accredited programs [52], to provide public transparency about which institutions were accredited and could issue valid degrees. Earlier in the year, the ministry placed several universities on probation [53] when they failed to meet licensing and accreditation standards; the move was part of an ongoing effort to enforce quality and crack down on subpar institutions.

Considerations for U.S. Institutions

As of this writing, court-room wrangling over the legality of the travel ban [54] was ongoing. For now, it remains unclear whether the ban will be upheld, and difficult to predict just how profound the impact on international enrollments will be. However, the immediate impact of the executive order was stark, with protestors swarming international airports in the U.S. even as customs officials refused to process travelers from bound countries, instead holding them in custody for hours. Students already enrolled at U.S. institutions, meanwhile, immediately began to experience repercussions, with universities advising them to avoid travel if at all possible. Almost immediately following news about the order, reported The Atlantic [55], “MIT sent an email to its international scholars advising them to ‘consider postponing any travel outside of the U.S.’ until the executive orders had been clarified. Harvard University sent a similar email … adding that since ‘the executive order also contemplates that additional countries could be added to the banned list … all foreign nationals should carefully assess whether it is worth the risk to travel outside the country.'”

The question institutions face now is how to adjust course in the face of sudden change.

NOTE: One starting point for developing comprehensive supports for students from affected countries is nuanced insight into the needs of students from affected parts of the world. In October 2016, WES published research on the motivations and challenges faced by international students from around the world. This issue of WENR features deeper insights into the experiences of students from the Middle East and North Africa. For more, please read “Students From the Middle East and North Africa: Campus Experiences and Areas of Need [37]” by Megha Roy and Ning Luo.

Immediate Triage, Programmatic Responses, Student Support, and Planning for the Long Haul

The most immediate need, of course, is to ensure that current students from affected countries receive timely and accurate information about a dynamic visa situation. Steps to educate faculty and staff, and to proactively address student concerns are of particular importance. In the immediate aftermath of the January 2017 travel ban, many universities responded [56] with letters of support [57] for international students. In most cases, these letters also included resources to help affected students respond and ensure their visa status was not unnecessarily jeopardized. Relevant resources include information about immigration law clinics, contact information for international student and scholar services, and numbers for student counseling offices equipped to provide psychological support as needed.

Institutions should also strive to maintain their reputations as intellectual havens that welcome and support students from all nations. Research by WES and others shows that international students who have positive experiences on U.S. campuses help to spread the word about those institutions back home. Students who feel well-supported can help ensure that universities’ reputations remain intact abroad. Programmatic approaches to these students are critical. But so are explicit broadcasts of support. Social media offers one way for institutions to overtly signal their support for students from the region. One such effort employs the hashtag #YouAreWelcomeHere [58].” The effort to do this is well underway at a more coordinated level as well: The Association of American Universities (AAU) 62 members released a statement [59]urging government officials to bring the travel ban to a rapid conclusion.

In the end, both current immigration policies and international student mobility patterns will shift. Those institutions that take definitive steps to embrace, support, and stand up for their international students will be well-positioned for a more open, and welcoming future.

References

| https://books.google.com/books?id=zi-vCgAAQBAJ&pg [9] | |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Although all three countries were top 25 contributors of international students to the U.S. in 2015/16, it’s debatable whether or not Egyptian and U.S. higher education institutions are actually in competition for the same pool of students. It may be that Egyptian institutions attract students who are primarily interested in Islamic studies (a strong feature of many Egyptian institutions) or who are seeking to enroll in institutions in a culture similar to those of their countries of origin. |

| ↑3 | UIS data is somewhat dated. The number reported by UIS in January 2017 was 2,928; the most recent number available from the Institute of International Education’s Open Doors 2016 report is 3,442, which represents a 15.7% increase over the previous year’s 2,974 students. |

| ↑4 | QS notes that “When considering only the top 50, … the United Arab Emirates is on a par with Saudi Arabia – each has 10 institutions ranked at this level.” |

| Al-Fanar Media [11] reported that “Egyptian universities have begun the academic year with no new government-sponsored master’s degree and Ph.D. students from Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Qatar’s Ministry of Higher Education excluded Egyptian universities from its list of approved universities, meaning that even if a Qatari student attended an Egyptian university at his own expense, his degree would not be recognized at home.” |