By WES Staff

This education profile describes recent trends in Nigerian education and student mobility, and provides an overview of the structure of the education system of Nigeria. This version is adapted from earlier versions by Jennifer Onyukwu, Nick Clark, and Caroline Ausukuya, and has been updated to reflect the most current available information

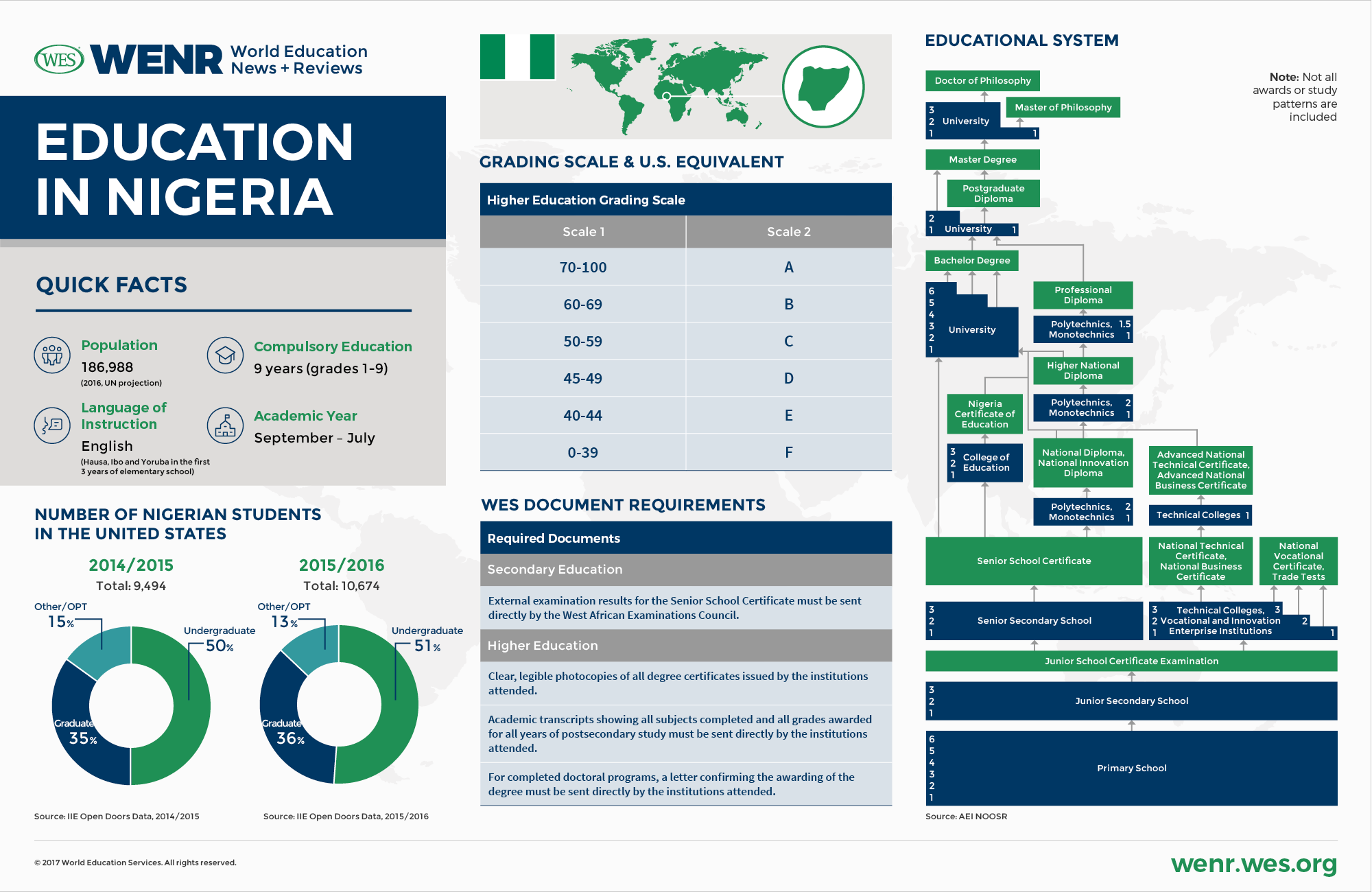

Almost one in four Sub-Saharan people reside in Nigeria, making it Africa’s most populous country. It’s also the seventh most populous country in the world, one with ongoing growth. From an estimated 42.5 million people at the time of independence in 1960, Nigeria’s population has more than quadrupled to 186,988 million people in 2016 (UN projection [2]). The United Nations anticipates that Nigeria will become the third largest country in the world by 2050 with 399 million people.[1] Medium Range Projection. United Nations. 2015. World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, accessed February 2017, https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/publications/files/key_findings_wpp_2015.pdf

The country is of growing economic importance as well. In mid-2016, it overtook South Africa as the largest economy on the African continent, and was, until recently, viewed as having the potential to emerge as a major global economy [3]. However, a substantial dependency on oil revenues has radically undercut this potential. Frankie Edozien, director of New York University’s Reporting Africa program, recently noted in The New York Times [4] that crude oil “is responsible for more than 90 percent of [Nigeria’s] exports [5] and 70 percent of its government revenues.” A sharp decline in crude oil prices from 2014 to early 2016 catapulted Nigeria into a recession [6] that added to the country’s already long list of problems: the violent Boko Haram [7] insurgency, endemic corruption [8], and challenges common to many Sub-Saharan countries: low life expectancy, inadequacies in public health systems, income inequalities, and high illiteracy rates.

Severe cuts in public spending following the recession have affected government services nationwide. In the education sector, the situation has exacerbated existing problems. Ongoing student protests and strikes have rocked Nigerian universities for years, and are a symptom of a severely underfunded higher education system. Austerity measures adopted by the Nigerian government in the wake of the current crisis further slashed education budgets. Students at many public universities in 2016 experienced tuition increases and a deterioration of basic infrastructure [9], including shortages in electricity and water supplies. The crisis also dried up scholarship funds for foreign study, placing constraints on international student flows from Nigeria.

Despite these constraints, the country will likely remain a dynamic growth market for international students. This is largely because of the overwhelming and unmet demand among college-age Nigerians. Nigeria’s higher education sector has been overburdened by strong population growth and a significant ‘youth bulge.’ (More than 60 percent of the country’s population is under the age of 24.) And rapid expansion of the nation’s higher education sector in recent decades has failed to deliver the resources or seats to accommodate demand: A substantial number of would-be college and university students are turned away from the system. About two thirds of applicants who sat for the country’s national entrance exam in 2015 could not find a spot at a Nigerian university.

International Mobility Trends: The Top African Sender of Students

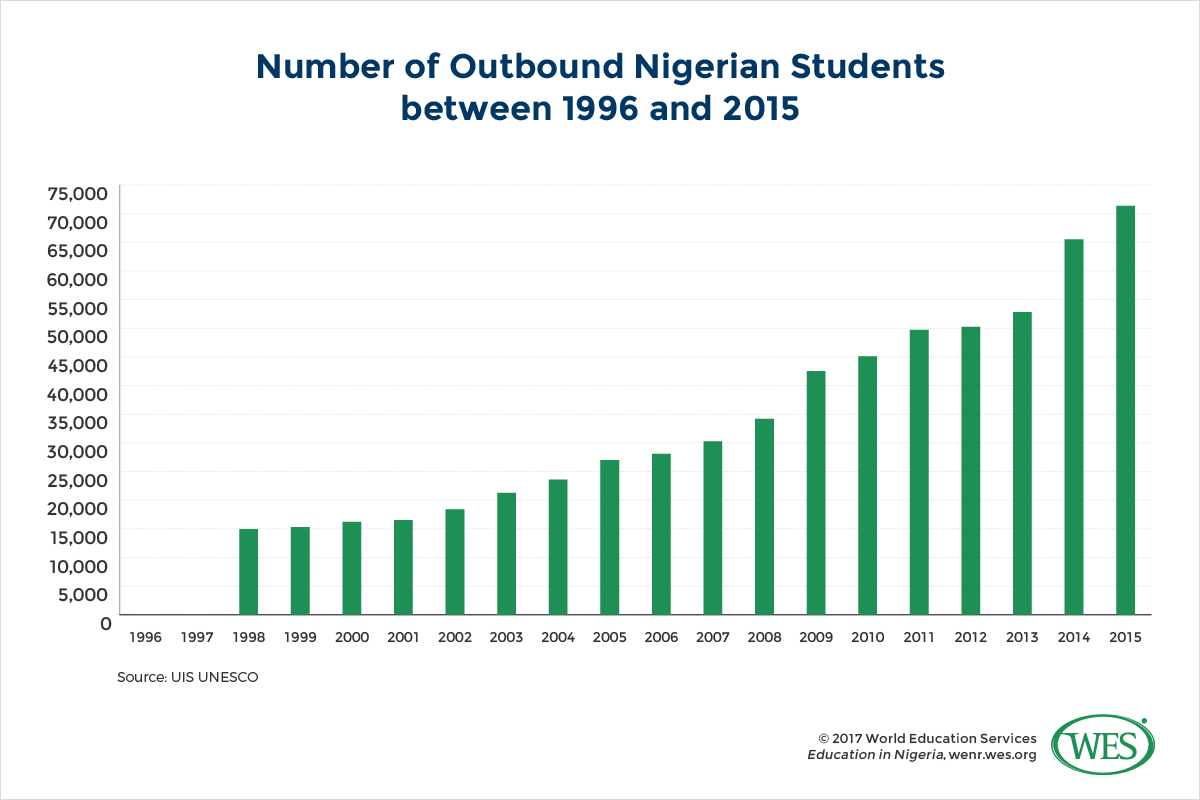

Nigeria is the number one country of origin for international students from Africa: It sends the most students overseas of any country on the African continent, and outbound mobility numbers are growing at a rapid pace. According to data from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics [10] (UIS), the number of Nigerian students abroad increased by 164 percent in the decade between 2005 and 2015 alone– from 26,997 to 71,351.[2]Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies.

In the short term, Nigeria’s oil price-induced fiscal crisis is likely to affect outbound student mobility. As many as 40 percent of Nigerian overseas students [12] are said to rely on scholarships, many of which were backed by oil and gas revenues. The vast majority of these scholarships have been scaled back or scrapped altogether in the wake of the fiscal crisis. Further exacerbating the immediate prospects of Nigeria’s overseas students was a 2016 crash of the foreign exchange rate of Nigeria’s currency, the naira. The crash increased costs for international students, and reportedly [13] left large numbers of Nigerian overseas students unable to make tuition payments.

But for all the short term upheaval, the push factors that underlie the outflow of students in Nigeria are fundamentally unchanged. These include:

- The failure of Nigeria’s education system to meet booming demand

- The often poor quality of its universities

- Rapid growth in the number of middle class families [3] who can afford to send their children overseas

Given those drivers, it seems unlikely that the crisis will lead to a sharp and prolonged downturn of international student numbers.

Destination Countries

Due to colonial ties and a shared language, the United Kingdom has long been the favorite destination for Nigerian students overseas with numbers booming in recent years. Some 17,973 Nigerian students studied in the UK in 2015 [14] .

In line with a general shift towards regionalization in African student mobility, Nigerian students in recent years have been increasingly studying in countries on the African continent itself. Ghana has recently overtaken the U.S. as the second-most popular destination country, attracting 13,919 Nigerian students in 2015, according to the data provided by the UNESCO Institute of Statistics [15] (UIS).

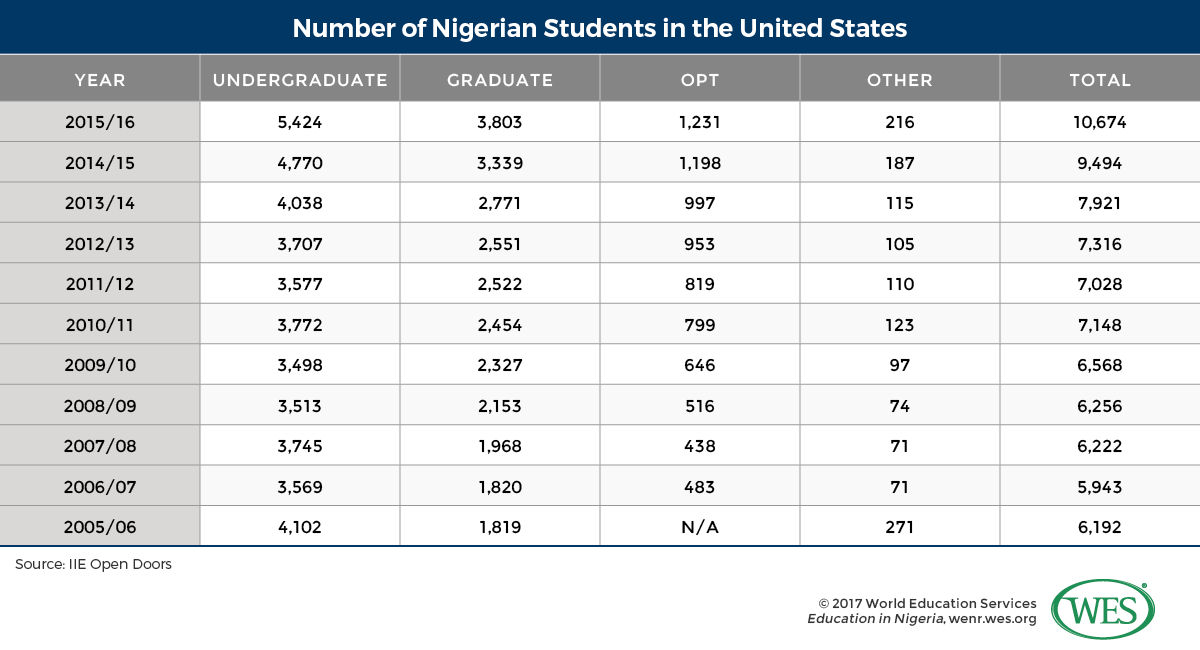

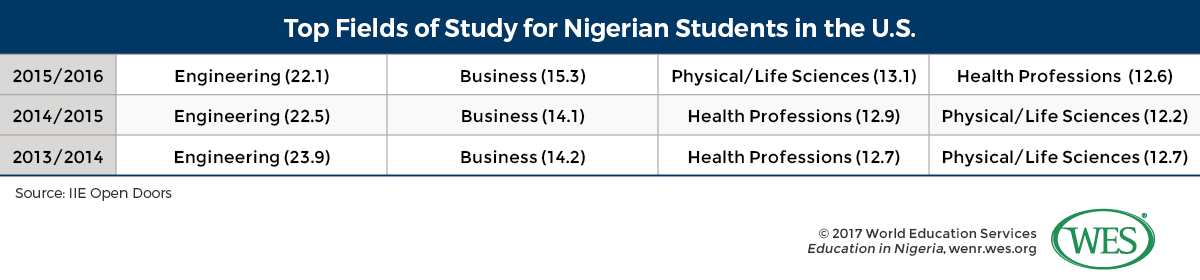

Despite this repositioning, the U.S. remains a highly popular study destination. Nigerian enrollments in U.S. institutions have been increasing slowly but steadily over the past 15 years from 3,820 in 2000/01 to 10,674 in 2015/16, according to the Open Doors data [16] provided by the Institute of International Education (IIE). Nigerian students are currently the 14th largest group among foreign students in the United States, and contributed an estimated USD $324 million to the U.S. economy in 2015/16. Engineering, business, physical sciences, and health-related fields continually rank as the most popular fields of study among Nigerian students enrolled at U.S. universities.

Another country that has more recently emerged as a popular destination for Nigerians, especially among those from the Muslim north, is Malaysia. Aside from the appeal of Malaysia as a majority Islamic country, low tuition and living costs are attractive, as is the opportunity to earn a prestigious Western degree from one of the several foreign branch campuses that operate in the country. As per UIS, 4,943 Nigerians were studying in Malaysia in 2015, making the country the fourth most popular destination country of Nigerian students. Another Muslim country that is increasingly attracting Nigerian students is Saudi Arabia, which in 2015 hosted 1,915 students from Nigeria.

In Brief: The Education System

Administration

Nigeria has a federal system of government with 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory of Abuja. Within the states, there are 744 local governments in total.

Education is administered by the federal, state and local governments. The Federal Ministry of Education is responsible for overall policy formation and ensuring quality control, but is primarily involved with tertiary education. School education is largely the responsibility of state (secondary) and local (elementary) governments.

The country is multilingual, and home to more than 250 different ethnic groups. The languages of the three largest groups, the Yoruba, the Ibo, and the Hausa, are the language of instruction in the earliest years of basic instruction; they are replaced by English in Grade 4.

Overall Structure

Nigeria’s education system encompasses three different sectors: basic education (nine years), post-basic/senior secondary education (three years), and tertiary education (four to six years, depending on the program of study).

According to Nigeria’s latest National Policy on Education (2004), basic education covers nine years of formal (compulsory) schooling consisting of six years of elementary and three years of junior secondary education. Post-basic education includes three years of senior secondary education.

At the tertiary level, the system consists of a university sector and a non-university sector. The latter is composed of polytechnics, monotechnics, and colleges of education. The tertiary sector as a whole offers opportunities for undergraduate, graduate, and vocational and technical education.

The academic year typically runs from September to July. Most universities use a semester system of 18 – 20 weeks. Others run from January to December, divided into 3 terms of 10 -12 weeks.

Basic Education

Elementary education covers grades one through six. As per the most recent Universal Basic Education guidelines [19] implemented in 2014, the curriculum includes: English, Mathematics, Nigerian language, basic science and technology, religion and national values, and cultural and creative arts, Arabic language (optional). Pre-vocational studies (home economics, agriculture, and entrepreneurship) and French language are introduced in grade 4.

Nigeria’s national policy on education stipulates [19] that the language of instruction for the first three years should be the “indigenous language of the child or the language of his/her immediate environment”, most commonly Hausa, Ibo, or Yoruba. This policy may, however, not always be followed at schools throughout the country, and instruction may instead be delivered in English. English is commonly the language of instruction for the last three years of elementary school. Students are awarded the Primary School Leaving Certificate on completion of Grade 6, based on continuous assessment.

Progression to junior secondary education is automatic and compulsory. It lasts three years and covers grades seven through nine, completing the basic stage of education. The curriculum includes the same subjects as the elementary stage, but adds the subject of business studies.

At the end of grade 9, pupils are awarded the Basic Education Certificate (BEC), also known as Junior School Certificate, based on their performance in final examinations administered by Nigeria’s state governments. The BEC examinations take place nationwide in June each year and usually last for a week. Students are expected to take a minimum of ten subjects and a maximum of thirteen. Students must achieve passes in six subjects, including English and mathematics, to pass the Basic Education Certificate Examination.

Crisis in Elementary Schooling

Like the country’s education system as a whole, Nigeria’s basic education sector is overburdened by strong population growth. A full 44 percent of the country’s population [20] was below the age of 15 in 2015, and the system fails to integrate large parts of this burgeoning youth population. According to the United Nations [21], 8.73 million elementary school-aged children in 2010 did not participate in education at all, making Nigeria the country with the highest number of out-of-school children in the world.

The lack of adequate education for its children weakens the Nigerian system at its foundation. To address the problem, thousands of new schools have been built in recent years. The Nigerian government has the official goal to universalize free basic education for all children. Yet, despite recent improvements in total enrollment numbers in elementary schools, the basic education system remains underfunded; facilities are often poor, teachers inadequately trained, and participation rates are low by international standards.

In 2010, the net enrollment rate at the elementary level was 63.8 percent [22] compared to a global average of 88.8 percent. According to recent statistics on completion rates [23], approximately one quarter of current pupils drop out of elementary school. These low participation rates perpetuate illiteracy rates in Nigeria, which, while relatively high compared to other Sub-Saharan countries, are well below the global average. The country in 2015 had a youth literacy rate of 72.8 percent and an adult literacy rate of 59.6 percent compared to global rates of 90.6 percent (2010) and 85.3 percent (201o), respectively (data reported by the World Bank [24]). Within Nigeria, there is a distinct regional difference in participation rates in education between the oil-rich South and the impoverished North of the country, in some parts of which elementary enrollment rates were reportedly below 25 percent in 2010.[3]International Organization for Migration. 2014. Promoting Better Management of Migration in Nigeria: Needs assessment of the Nigerian Education Sector. Abuja. Accessed February 2017, https://nigeria.iom.int/, p. 19.

Senior Secondary Education

Senior Secondary Education lasts three years and covers grades 10 through 12. In 2010, Nigeria reportedly had a total 7,104 secondary schools with 4,448,981 pupils and a teacher to pupil ratio of about 32:1.[4]Ibid., p. 20

Reforms implemented in 2014 have led to a restructuring of the national curriculum [25]. Students are currently required to study four compulsory “cross-cutting” core subjects, and to choose additional electives in four available areas of concentration. Compulsory subjects are: English language, mathematics, civic education, and one trade/entrepreneurship subject. The available concentration subjects are: Humanities, science and mathematics, technology, and business studies. The new curriculum has a stronger focus on vocational training than previous curricula, and is intended to increase employability of high school graduates in light of high youth unemployment in Nigeria.

In addition to public schools, there are a large number of private secondary schools, most of them expensive and located in urban centers. Many private schools include U.S. K-12, International Baccalaureate [26] or Cambridge International Examination [27] curricula, allowing students to take international examinations like the International General Certificate of Secondary Education [28] (IGSCE) during their final year in high school.

Senior School Certificate Examination

At the end of the 12th grade in May/June, students sit for the Senior School Certificate Examination (SSCE). They are examined in a minimum of seven and a maximum of nine subjects, including mathematics and English, which are mandatory. Successful candidates are awarded the Senior Secondary Certificate (SSC), which lists all subjects successfully taken. Students can sit for a second SSC annual exam if interested or if they need to improve on poor results in the May/June exams. [5]The General Certificate of Education O-Level Examination that was offered in Nigeria until 1989 has been replaced by a second annual SSC exam in November/December.

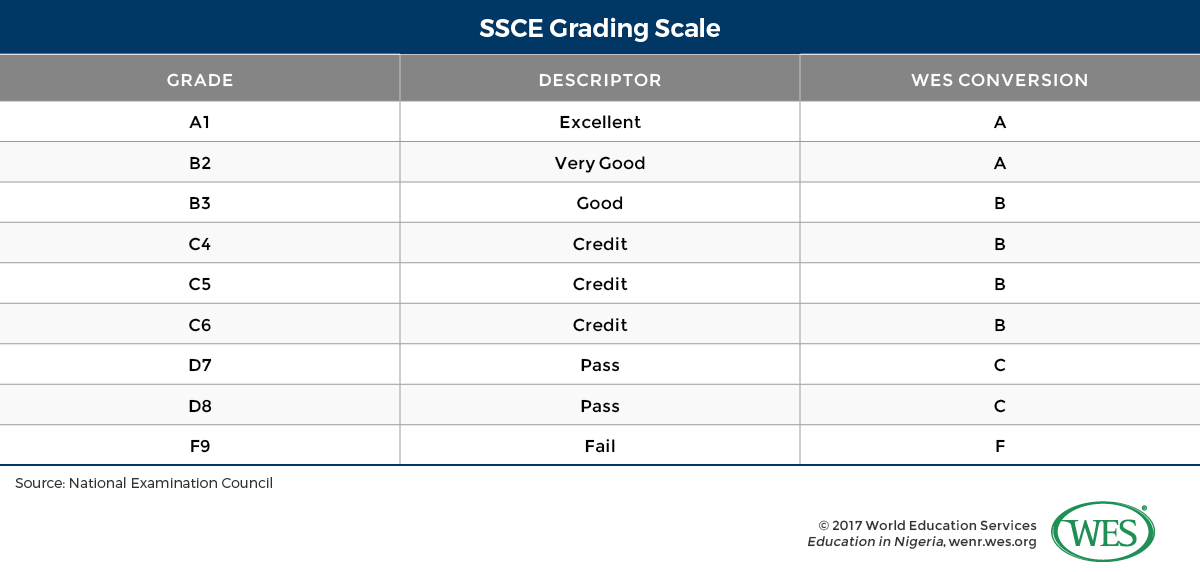

SSC examinations are offered by two different examination boards: the West African Examination Council [29] and the National Examination Council [30] (NECO). The examination is open to students currently enrolled in the final year of secondary school, as well external private candidates (in the November/December session only). The SSCE grading scale is as follows for both WAEC and NECO administered examinations:

Admission to public universities in Nigeria is competitive and based on scores obtained in the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination as well as the SSC results. (The Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination is discussed in greater detail below.) Most universities require passes in at least five SSC subjects and take into consideration the average score. Students must score an average grade of at least ‘credit’ level (C6) or better to be considered for admission to public universities; some institutions may require higher grades.

It is possible to access student results through the West African Examinations Council [32] (WAEC)/or National Examination Council [33] (NECO) websites. The student must provide the PIN number that they purchase for the equivalent of approximately USD $3 (available at banks, WAEC regional offices and online). With the PIN number it is possible to retrieve a printable copy of the WAEC results. This is the fastest and most reliable way of verifying a student’s results from Nigeria.

Vocational and Technical Education

The Nigerian education system offers a variety of options for vocational and technical education at both the secondary and post-secondary levels. To combat chronic youth unemployment, the Federal Ministry of Education presently supports a number of reform projects to advance vocational training, including the “vocationalization” of secondary education [34] and the development of a National Vocational Qualifications Framework [35] by the National Board for Technical Education, similar to the qualifications frameworks found in other British Commonwealth countries.

A two-tier system of nationally certified programs is offered at science technical schools, leading to the award of National Technical/Commercial Certificates (NTC/NCC) and Advanced National Technical/Business Certificates. The lower-level program lasts three years after Junior Secondary School and is considered by the Joint Admission and Matriculation Board as equivalent to the SSC.

The advanced program requires two years of pre-entry industrial work experience and one year of full-time study in addition to the NTT/NCC. All certificates are awarded by the National Business and Technical Examinations Board [36] (NABTEB).

Another type of – relatively new – vocational training institution are the so-called “Vocational Enterprise Institutions” (VEIs) and “Innovation Enterprise Institutions” (IEIs), established to provide employment-geared education in the private sector [37]. At the secondary level, VEIs offer programs for graduates of junior secondary school leading to a National Vocational Certificate (NVC). Programs are between one and three years in length and conclude with the award of the NVC Part 1, Part 2 and Final.

At the post-secondary level, IEIs offer diploma programs for holders of the SSC. Programs are two years in length (3-4 years part-time) and lead to the so-called National Innovation Diploma. As of 2017, there were 137 approved IIEs and 72 approved VEIs listed on the website of the National Board for Technical Education [38].

University Admissions

Until the 1970s, Nigerian universities set their own admissions standards. Due to the growing number of universities in Nigeria’s sprawling higher education system, this practice became problematic, and, in 1978, the Nigerian government established the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board [39] (JAMB) to oversee a centralized admissions test called the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examinations (UTME). The fiscal crisis of the Nigerian government has recently led to discussions about abolishing the JAMB as a cost-cutting measure [40]. In November of 2016, the JAMB announced [41] that it did no longer have adequate funds to effectively conduct the nation-wide UTME. Despite these financial difficulties, all public universities are presently mandated to use the governmental admissions test in their admissions decisions, even though some universities have additional requirements going beyond the UTME.

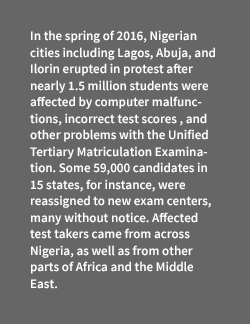

[42]The Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME) is a computerized standard test. The multiple-choice test is three hours in duration and conducted once a year, typically in March. It can be taken at test centers in each state of the Nigerian federation, as well as some overseas testing facilities.

[42]The Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME) is a computerized standard test. The multiple-choice test is three hours in duration and conducted once a year, typically in March. It can be taken at test centers in each state of the Nigerian federation, as well as some overseas testing facilities.

The UTME is open to students who achieve credit level or better in English and four other subjects in the SSC exams at the end of the senior secondary cycle. Students with equivalent qualifications like the National Technical Certificate may also be admitted.

Students who sit for the UTME must take exams in English and three subjects related to their intended major in order to be considered for admission into universities. A total of 23 different UTME subject combinations are offered in the fields of: Banking and finance, law, English and literary studies, mass communication, linguistics, philosophy, engineering, medicine and surgery, computer science, nursing, pharmacy, biochemistry, industrial chemistry, geology, mathematics, microbiology, economics, sociology, psychology, political science, public administration, and accounting and business administration.

Test takers can achieve a maximum score of 400. Most universities require a minimum score between 180 and 200, although high-demand universities or programs may require higher scores.

Many universities also conduct additional screening or post-UTME examinations before a final admission decision is made. These post-UTME requirements can be demanding and are often reported to be a source of frustration for Nigeria’s university applicants. In 2016, the JAMB announced a number of reforms, including stopping universities [43] from using written post-UTME exams, as well as changes to the UTME scoring system. As of February 2017, the status of the reforms was unclear, due to resistance from universities. Many universities continued to use post-UTME exams in the fall 2016 admissions cycle.

When registering with JAMB for the UTME, each student can apply to up to six institutions: two universities, two polytechnics, and two colleges of education, with first and second choice programs for each institution type. A number of universities accept applications for post-UTME admissions screening from students that that did not get into their universities of choice. Some private institutions accept applicants that did not sit for the UTME at all.

Not Enough University Seats

According to the statistics JAMB provides on its website [44], a total of 1.579,027 students sat for the UTME exam in 2016. 69.6 percent of university applications were made to federal universities, 27.5 percent to state universities, and less than 1 percent to private universities. The number of applicants currently exceeds the number of available university seats by a ratio of two to one. In 2015, only 415.500 out of 1.428,379 applicants were admitted to university, according to the data provided by JAMB.

This admission ratio, low as it may be, is a significant improvement versus 10 years ago when the ratio was closer to one in ten for university entry. But the admissions crisis continues to be one of Nigeria’s biggest challenges in higher education, especially given the strong growth of its youth population. Nigeria’s system of education presently leaves over a million qualified college-age Nigerians without access to postsecondary education on an annual basis.

High unemployment among university graduates is also a major problem, but does not appear to be a deterrent to those seeking admission into institutions of higher learning. In 2016, the online magazine Quartz reported [45] that a staggering 47 percent of Nigerian university graduates were without employment, based on a survey of 90,000 Nigerians.

Tertiary Education: An Overview

Universities

The National University Commission (NUC), the government umbrella organization that oversees the administration of higher education in Nigeria, listed 4o federal universities, 44 state universities and 68 private universities as accredited degree-granting institutions on its website as of 2017.

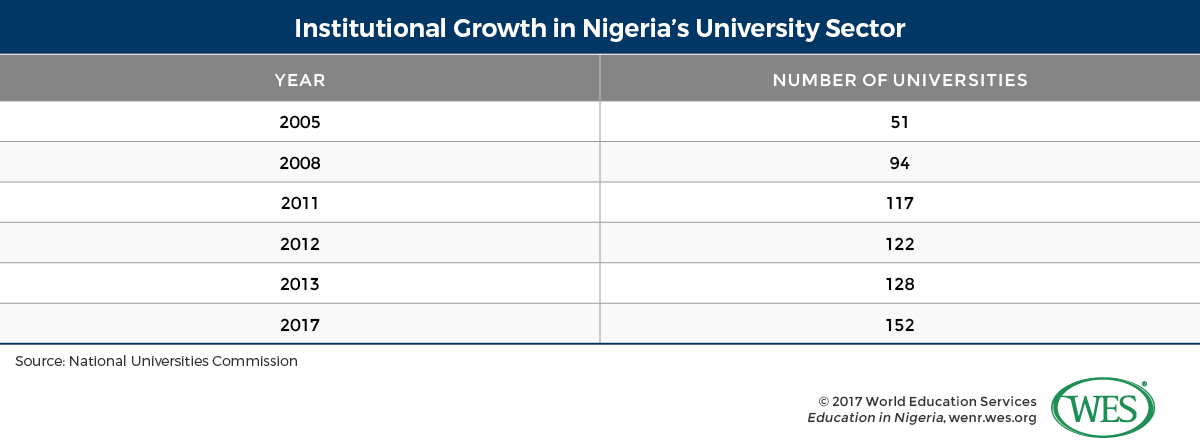

Many of these insitutions are relatively new. In response to demographic pressures Nigeria’s higher education sector expanded over a relatively short period. In 1948, there was only one university-level institution in the country, the University College of Ibadan, which was originally an affiliate of the University of London. By 1962, the number of federal universities had increased to five: the University of Ibadan, the University of Ife, the University of Nigeria, Ahmadu Bello University, and the University of Lagos.

Between 1980 and 2017, the number of recognized universities has grown tenfold from 16 to 152, as reported by Nigeria’s National Universities Commission [46].https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/32225370.pdf [47]For the first few decades of growth, higher education capacity building was primarily in the public sector, driven by Federal and State governments. More dramatic growth occurred beginning in the late 1990s, when the Nigerian government began to encourage the establishment of private universities. Since then, private institutions, which constitute some 45 percent of all Nigerian universities as of 2017, have proliferated at a rapid pace, from 3 in 1999 to 68 in 2017. About two thirds of these institutions are estimated [48] to be religiously affiliated schools. Despite the sheer number of private institutions that have opened, enrollments seem to be relatively low. Although estimates are difficult to find, the small number of United Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME) applications to private universities indicates that private universities account for only a small percentage of Nigeria’s total tertiary enrollment, which UIS [21] reported as 1,513, 371 as of 2011.reportedly [49] had a total enrollment of 6,822 students in 2010/2011.

Nigeria’s 40 federal universities as well as dozens of teaching hospitals and colleges are under the direct purview of the NUC. State governments have responsibility for the administration and financing of the 44 state universities.

In addition to granting institutional accreditation, the NUC approves and accredits all university programs. Accreditation is granted for an initial three-year period and subsequent five-year periods. (For a detailed overview of the process see the NUCs 2012 accreditation manual [51]). The suspension of accreditation for programs is not uncommon. In 2016, for example, the NUC publicized a list of 150 unaccredited degree programs at 37 universities [52].

Colleges and Polytechnics

In addition to universities, there are a large number of polytechnics and colleges under the purview of the National Board of Technical Education [53] (NBTE), the federal government body tasked with overseeing technical and vocational education. In 2017, the NBTE recognized 107 polytechnics, 27 monotechnics, and 220 colleges in various specific disciplines. These institutions were established to train students for technical and mid-level employment.

The National Commission for Colleges of Education [54] is the federal body dedicated to overseeing non-university teacher education. As of 2017, there were 84 teacher training colleges in Nigeria.

One Key Challenge: Underfunding

One of the most pressing problems for Nigeria’s higher education system remains the severe underfunding of its universities. The Federal government, which is responsible for sustaining public universities, has over the past decade not significantly increased the share of the government budget dedicated to education, despite exploding student numbers. Between 2003 and 2013 education spending fluctuated from 8.21 percent of the total budget in 2003 to 6.42 percent in 2009, and to 8.7 percent in 2013 [55]. In 2014, the government significantly increased education spending to 10.7 [56] percent of the total budget, but it remains to be seen if this share can be maintained following the oil price-induced fiscal crisis. Recent reports [57] suggest that current spending levels have already decreased well below 10 percent.

Due to funding constraints, most of Nigeria’s public universities are in deteriorating condition. And while efforts at increasing capacity by building new universities have generally been positive for access in absolute terms, they have also created issues related to instructional quality. Nigeria’s institutions and lecture halls are severely overcrowded, student to teacher ratios have skyrocketed, and faculty shortages are chronic. Lab facilities, libraries, dorms, and other university facilities are often described as in being in a state of decay. A large proportion of lecturers at universities are assistant professors without doctoral degrees: Reports from 2012 suggested that only 43 percent of Nigeria’s teaching staff held Ph.D. degrees, and that Nigeria had one of the worst lecturer-to-student ratios in the world.[8] International Organization for Migration. 2014. Promoting Better Management, p. 21. The University of Abuja and Lagos State University, for example, reportedly had lecturer to student ratios as high as 1:122 and 1:114 respectively.[9]Ibid.

Although rankings are a notoriously poor proxy for university quality, they do provide the best relative guide available. It’s thus worth noting that, in 2017, only one of Nigeria’s universities is currently listed among the top 1,000 in international university rankings in the Times Higher Education Ranking [58] – the University of Ibadan at 801. Universities from other African countries like South Africa, Ghana, and Uganda are ranked considerably higher.

Over the past decade, strikes have become an almost ritual occurrence at Nigerian universities, disrupting lectures, causing delayed graduations, the loss income for university staff, and further eroding the already low trust in the education system. In 2013, 60 public universities were paralyzed by strikes for more than five months over demands for funding increases and better employment benefits for university staff. In 2016, strikes, likewise, disrupted classes at 10 federal and state universities [59] .

Another Key Challenge: Academic Corruption and Fraud

While corruption is a covert activity that is difficult to measure, Nigeria scores low on the global “Corruption Perceptions Index” published by the organization Transparency International. The 2016 report [60] places Nigeria at 136th place among 176 countries.

Nigeria’s education sector is particularly vulnerable to corruption. As corruption scholar Ararat Osipian noted in 2013, “[l]imited access to education [in Nigeria] has no doubt contributed to the use of bribes and personal connections to gain coveted places at universities, with some admissions officials reportedly working with agents to obtain bribes from students. Those who have no ability or willingness to resort to corruption face lost opportunities and unemployment.”https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/global_corruption_report_education [61], 149. In 2013, Transparency International reported that about 30 percent of Nigerians surveyed said they had paid a bribe in the education sector.https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/global_corruption_report_education [61], 8.

Australian scholar Tracey Bretag summarized the conditions when describing Nigeria as a country where “[a]cademic fraud is endemic at all levels of the … education system, and misconduct ranges from … cheating during examinations to more serious behaviours, such as impersonation, falsifying academic records, ‘paying’ for grades/certificates with gifts, money or sexual favours, terrorising examiners and assaulting invigilators”.https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/global_corruption_report_education [61], 173.

The West African Examinations Council (WAEC) has deemed it necessary to start using biometric fingerprint technology when admitting students to SSC examinations. In 2015, WAEC stated that Nigeria had the highest number of cheating incidents [62] of all five countries in which the Council operates. the following year, WAECceased recognizing 113 Nigerian secondary schools [63] implicated in examination malpractice, and annulled the results of some 30, 654 candidates who sat for the 2012 SSC exams. The extent of fraud in university applications has caused the Council to develop an elaborate scratch-card system [64] that utilizes an online pin-code verification method to verify the authenticity of exam results.

Nigeria is also home to a substantial number of diploma mills and institutions of dubious quality in Nigeria.

Note: The prevalence of fraud is apparent in credential reviews at WES; forged Nigerian degrees and other credentials are, by comparison to documents received from many other countries, relatively common. For this reason WES goes to great lengths to verify the authenticity of academic documents from Nigeria.

Promised Reforms

The NUC has, in recent years, closed a large number of illegal degree mills. In 2013, it shut down 41 such entities [65], and in 2014 the Council closed an additional 55 degree mills [66] while investigating 8 additional schools. For current information on degree mills, the NUC has started to publish a “list of illegal universities [67]”, most recently in 2016.

Other government reforms and initiatives have sought to improve the Nigerian higher education system as well. These include the upgrade of some polytechnics and colleges of education to the status of degree-awarding institutions, the approval and accreditation of more private universities, and the dissemination of better education-related data. In 2016 alone, the federal government granted approval for the establishment of eight new private universities [68]. In 2013, the federal government announced plans [69] to create six regional ‘mega-universities’ with the capacity to admit 150,000 to 200,000 students each. As of February 2017, however, there was no indication that this ambitious project would be realized in the near future.

Degree Programs

Nigeria’s university system resembles that of the United States – it includes an undergraduate bachelor’s degree followed by a master’s degree, and a doctoral degree. The system includes postgraduate diplomas, as well as non-university National Diploma, and Higher National Diploma programs.

Bachelor’s Degree

The standard duration of undergraduate Bachelor programs in Nigeria is four years in most academic disciplines, including sciences, social sciences, and humanities. The most commonly awarded credentials in these fields are the Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science, and Bachelor of Social Science. Most universities use a credit system and require between 120 and 160 credits for four-year programs.

Students may take either a single-subject honors degree, or combined honors.

- For single-subject honors, students study three subjects in the first year, two in the second year, and one in the third.

- In the combined honors program students take three subjects in the first year and two subjects in both the second and third years.

- In the fourth year, single subject honors students take one subject and combined-honors students take at least two subjects.

Programs in engineering- and technology-related fields are typically five years in duration, require between 140 and 170 credits, and conclude with the award of Bachelor of Engineering or Bachelor of Technology degrees.

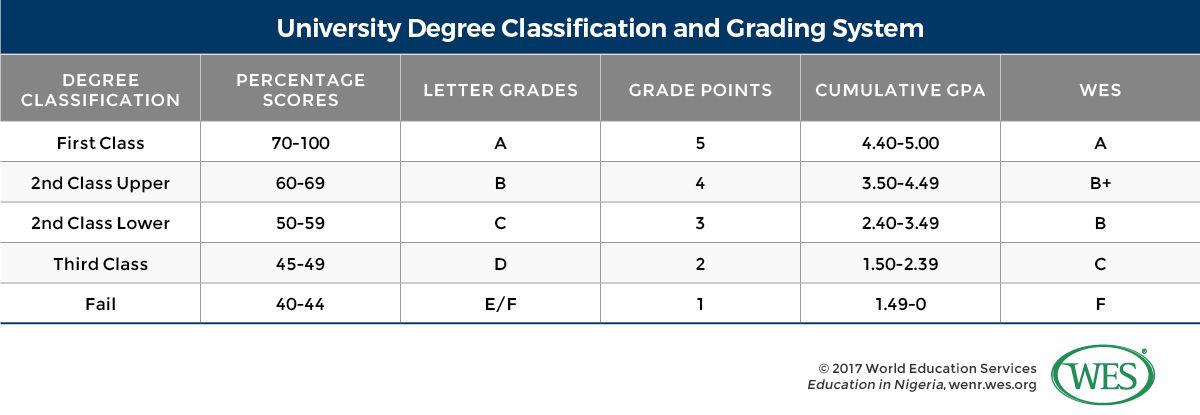

University Degree Classification and Grading System

Nigerian universities use a degree classification system that ranks the overall performance of students in bachelor’s degree programs. The degree classification is relevant for graduate admissions and employment prospects. The NUC recently changed the classification system, eliminating the previously used classification of “PASS”, thereby increasing the GPA requirements for graduation. The new system is increasingly used nationwide, although many institutions have not yet adopted the system as of February 2017. The new NUC classification system and a number of common grading scale variations are outlined below, but classification systems and grading scales may vary greatly from institution to institution.

Graduate Programs

Postgraduate diplomas are non-degree programs awarded upon completion of one year of full-time graduate study after the bachelor’s degree. These programs are offered in a variety of disciplines, although most of them have a more applied rather than research-oriented focus. The postgraduate diploma does not give access to doctoral programs, which typically require a master’s degree for admission.

The most commonly awarded master’s degrees are the Master of Arts and Master of Science. Admission requirements can vary, but most universities require a First or Second Class bachelor’s degree for admission. (See classification system below.) Programs are either one or two years in length. Two year programs typically require a thesis, while one-year programs are generally only course-work-based.

The Master of Philosophy is a short, advanced research degree. It is required by some universities for admission into doctoral programs. Programs are either completely research-based or include coursework in addition to research. Coursework completed in M.Phil. Programs can usually be transferred into doctoral programs.

The standard doctoral degree is the Doctor of Philosophy. It is a research degree that takes three years of study beyond the master’s or M.Phil. degree. Completion of the program requires a dissertation and oral defense. Some programs may also include a limited amount of coursework.

Professional Degrees

First professional degrees in medicine, dentistry, and veterinary science are six years in length and usually require completion of a clinical internship. The standard credentials in these disciplines fulfill the academic requirements for professional licensure in Nigeria, and include the Bachelor of Medicine-Bachelor of Surgery, Bachelor of Dental Surgery, and Doctor of Veterinary Medicine.

The Bachelor of Architecture is a five-year entry-to-practice degree. Bachelor of Law degrees can be either four or five years in length, depending on the institution.

Teacher Education

Teachers in the basic education sector are required to have a Nigerian Certificate of Education (NEC) awarded by one of Nigeria’s teacher training colleges. Admission to the three-year NEC programs requires the Senior Secondary School Certificate and adequate scores in a matriculation test, called the “Monotechnics, Polytechnics and Colleges of Education” exam (MPCE), that is administered by Nigeria’s Joint Admissions and Matriculations Board (JAMB). Some programs include an in-service teaching internship.

Teachers at senior secondary level must have university training. Students can earn either a Bachelor of Education degree or a Postgraduate Diploma in Education following a Bachelor’s degree in another discipline.

Technical and Vocational Education

Higher technical and vocational education is provided at technical colleges, polytechnics, and monotechnics. Entry into these institutions is based on the JAMB-MPCE exam combined with results from upper secondary school. There are two main qualifications:

- The National Diploma (ND) is a two-year program that combines theoretical instruction with practical training. Many programs include a mandatory industrial placement component.

- The Higher National Diploma (HND) is the second stage of education at technical colleges, polytechnics, and monotechnics. It follows the ND, which is typically required for admission. The program is two years in length, theoretical instruction is at a higher level than at the ND level, and there is usually less emphasis on practical training. The HND gives students access to some Postgraduate Diplomas at universities.

In addition to the ND and HND, colleges and specialized training institutes offer programs in nursing and allied health fields. The Nursing & Midwifery Council of Nigeria [71] awards the Certificate of Registration in Nursing upon completion of a three-year training program at nursing schools. The certificate entitles holders to practice nursing in Nigeria. Upon one additional year of study in midwifery, the Council also awards a Certificate of Registration in Midwifery. The Institute of Medical Laboratory Technology awards the Associate Diploma of Medical Laboratory Technology and the Fellowship Diploma on the basis of 4+1 years of postsecondary education.

WES Document Requirements

Secondary Education

External examination results for the Senior School Certificate are sent directly to WES by the West African Examinations Council (WAEC).

University Education

A typical transcript from a Nigerian university should have the student’s name, registration number, year of entry, year of graduation, GPAs, and CGPA, and semester-by-semester entry of all the completed courses and scores. Transcripts also include the signature of the Registrar or Deputy Registrar and an official stamp (some universities may attach student photographs and a university seal to strengthen the document.) Students are not given copies of their transcript. Universities send all transcripts directly to requesting institutions.

WES requires:

- Clear, legible photocopies of all degree certificates issued by the institutions attended

- Academic transcripts showing all subjects completed and all grades awarded for all years of study

These must be sent directly to WES by the institutions attended.

For completed doctoral programs, a letter confirming the awarding of doctorate must be sent directly to WES by the institutions attended.

Note: To verify a Nigerian university transcript, schools are advised to contact Nigerian universities directly through regular mail or email with addresses that can be found on their websites or on the NUC website [72].

Vocational and Professional Education (Polytechnics, Teacher Training Colleges, Colleges of Nursing and Midwifery)

WES requires:

- Clear, legible photocopies of all diplomas issued by the appropriate awarding authority (e.g. Certificate of Registration issued by the Nursing and Midwifery Council of Nigeria, Nigeria Certificate of Education)

- Academic transcripts showing all subjects completed and all grades awarded for all years of study.

These must be sent directly to WES by the institutions attended.

Sample Documents

This file of Sample Documents (pdf) [73] shows a set of annotated credentials from the Nigerian education system, beginning with the WAEC Senior School Certificate Examination results, followed by a National and Higher National Diploma, bachelor’s degrees, postgraduate diploma, and master’s and doctoral degrees.

References

| ↑1 | Medium Range Projection. United Nations. 2015. World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, accessed February 2017, https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/publications/files/key_findings_wpp_2015.pdf |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies. |

| ↑3 | International Organization for Migration. 2014. Promoting Better Management of Migration in Nigeria: Needs assessment of the Nigerian Education Sector. Abuja. Accessed February 2017, https://nigeria.iom.int/, p. 19. |

| ↑4 | Ibid., p. 20 |

| ↑5 | The General Certificate of Education O-Level Examination that was offered in Nigeria until 1989 has been replaced by a second annual SSC exam in November/December. |

| https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/32225370.pdf [47] | |

| ↑7 | More recent data from UIS are not available as of early 2017. |

| ↑8 | International Organization for Migration. 2014. Promoting Better Management, p. 21. |

| ↑9 | Ibid. |

| https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/global_corruption_report_education [61], 149. | |

| https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/global_corruption_report_education [61], 8. | |

| https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/global_corruption_report_education [61], 173. |