Mini Gu, Quality Assurance Specialist, WES

A quick scan of the higher education news coming out of Africa shows both progress and setbacks in recent months. Some snapshots:

- South Africa, Egypt ,and Tunisia [1] placed among the top 50 global producers of peer-reviewed science and engineering publications in 2016, according to the American National Science Foundation’s ranking index. Meanwhile, the ongoing crisis [2] over tuition fees in South Africa threatens the systemwide stability [3] of the country’s higher education sector, as reputable campuses shut down [4], international students at South African research institutions see their research capacity threatened [5], and the government seeks to stamp out diploma mills.

- Kenyan universities [6] saw a 22.8 percent year-over-year spike in enrollments in 2015, thanks to increased enrollments among women, massive infrastructure development, and a proliferation of new courses and new campuses. However, fast-paced growth in the number of campuses and universities and underfunding have led to a meltdown in quality, with little relief in sight and enrollments are expected to grow by another 20 percent in 2017. To close the funding gap, Kenya’s government asked universities to find new ways to generate income [7]. Kenyatta University – which has the nation’s largest enrollment – sought to comply, with investments in “a mall, a gas station, and other enterprises.”

- The World Bank is assisting the governments of eight countries in Eastern and Southern Africa with USD $140 million to establish several regional centers of educational and research excellence [8]. The project will last five years, include, university research centers from 24 institutions, and enroll an estimated 3,500 graduate students, including more than 700 Ph.D. students. It has a fixed female quota of at least 1,000 students.

- A new Continental Education Strategy for Africa [9], approved by 10 heads of state attending the 26th African Union Summit in 2016, seeks to promote postgraduate and post-doctoral education, and seeks to foster young academics, international research cooperation, and institutional links. Meanwhile, a lack of quality data [10] is hampering the development of transnational education policies that could expand access to higher education in Africa.

African Outbound Mobility: Rates, Drivers, and New Destinations

The net is that many of the most highly motivated students from across Africa seek placement abroad. According to some estimates, more than one in 10 international students in the world is African [11]. Some 5.8 percent of the continents tertiary-level African students enroll in institutions abroad – a share of outbound mobility that reportedly beats out that of any other region in the world.[1]Kritz, M. M. (2015), International Student Mobility and Tertiary Education Capacity in Africa. International Mirgation, Volume 53, Issue 1

February 2015, pp. 29–49 These numbers are on a generally upward trend, rising from 239,179 students in 2000 to 373,303 in 2013, according to UNESCO data.[2]Data from UNESCO’s Institute of Statistics, accessed in February 2017. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute for International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent. In some cases, organizations may report substantially different numbers of inbound or outbound international students from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. As the snapshots above indicate, the reasons for this high rate of mobility are legion. A surging youth population; focus on access to and completion of primary and secondary education; increasing urbanization; a broader range of job opportunities requiring education; low employment rates – all come together to create a wave of demand for tertiary-level seats.

Where they might head is an open question. As a rule, globally mobile African students have tended to enroll in institutions in countries that have either (or both) past colonial or current linguistic ties to their homelands: Students from Algeria, Morocco, the Ivory Coast, Mali, and other former French colonies head to in institutions in France. Students from Egypt, Kenya, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, and Uganda flow towards the U.K. Significant numbers of students from Africa, particularly Nigeria, come to colleges and universities in the U.S. [See related article in this issue: African Student Mobility: Regional Trends and Recommendation for U.S. HEIs [12]]

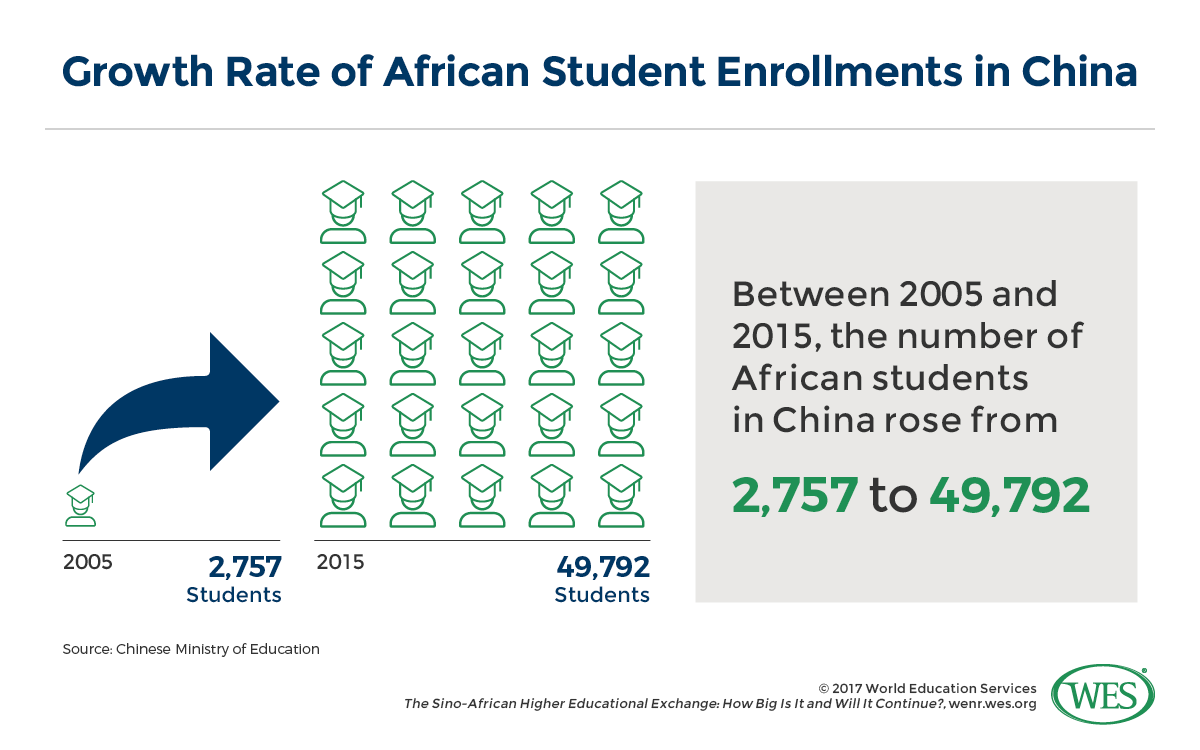

In recent years, however, trends have changed. In the last decade, an increasing number of African students have begun to head to China. The growth rate has been striking — a 35 percent average annual increase, according to China’s Ministry of Education (MoE). Between 2005 and 2015, MoE reports that Africa students numbers in China rose from 2,757 to 49,792 [13].[3]Data from China’s Ministry of Education, accessed in February 2017. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute for International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies.

Six Decades of Sino-African Educational Exchange (Mostly One Way)

Such Sino-African educational exchanges started small. They can be traced back to 1956, when the still young People’s Republic of China first established diplomatic ties with Egypt, and the two countries exchanged 8 students and teachers. In the decades since, China has established formal diplomatic relations with the majority of Africa’s 54 nations [15], and radically expanded its presence across the continent. A combination of private Chinese investments, along with government loans and aid (now in the range of tens of billions of dollars) help to support African infrastructure development, agriculture, transportation, public health efforts, finance and banking, and more. China also has an interest in Africa’s natural resources, including oil and copper. These considerations – as well as a need for African nations’ support in international forums such as the United Nations[4]Africa in China’s Foreign Policy, John L. Thornton, pp. 15-16 – form the backdrop for China’s increased interest in the post-secondary qualifications of Africans.

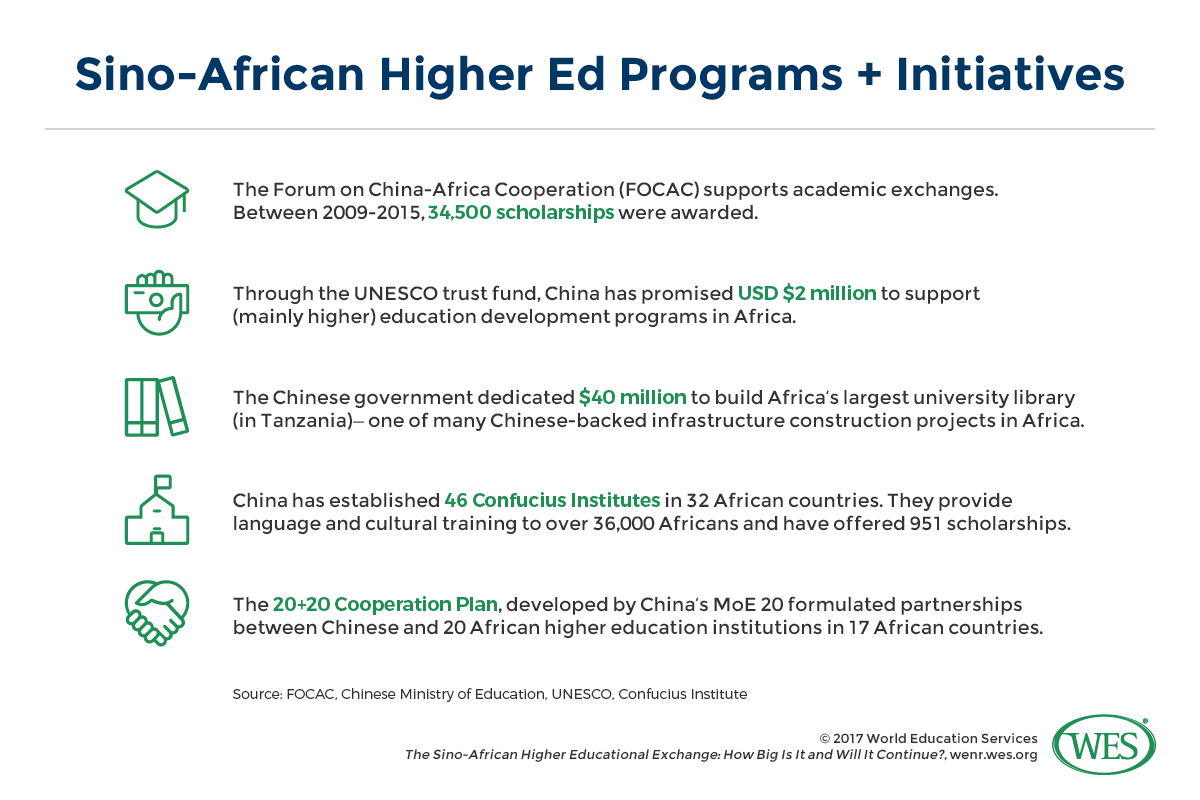

[16]In 2000, a newly formed Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) sought to establish a framework for China to coordinate its multiple diplomatic relationships with African nations. The forum includes China and, as of 2017, every Africa nation. Over time, post-secondary education has emerged as one focal point of the organization’s agenda. The education-related initiatives [17] that FOCAC supports span a wide range of areas. They support academic exchanges, government scholarships, cooperative higher education and research projects, technical and vocational training, distance education, language instruction, mutual recognition of academic qualifications, and more. Between 2010 and 2014, FOCAC distributed a reported 33,866 Chinese government scholarships [18] to African students, and the organization certainly seems poised to go on funneling a substantial number of African enrollments to Chinese institutions. At the third FOCAC ministerial conference in 2006, then- president Hu Jintao announced that China would increase scholarships for African students from 2,000 to 4,000 before 2009. The FOCAC-initiated African Talents Program [19], announced in 2012, sought to train 30,000 African professionals in China between 2013 and 2015, and provided students with 18,000 government scholarships. In late 2015, at the sixth FOCAC ministerial conference in Johannesburg, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced [20] plans to further increase aid to post-secondary African students, with 30,000 additional scholarships; 2,000 post-graduate and doctoral slots at top Chinese institutions, and short-term, sponsored, visits to China for 200 African scholars and 500 African youths.

[16]In 2000, a newly formed Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) sought to establish a framework for China to coordinate its multiple diplomatic relationships with African nations. The forum includes China and, as of 2017, every Africa nation. Over time, post-secondary education has emerged as one focal point of the organization’s agenda. The education-related initiatives [17] that FOCAC supports span a wide range of areas. They support academic exchanges, government scholarships, cooperative higher education and research projects, technical and vocational training, distance education, language instruction, mutual recognition of academic qualifications, and more. Between 2010 and 2014, FOCAC distributed a reported 33,866 Chinese government scholarships [18] to African students, and the organization certainly seems poised to go on funneling a substantial number of African enrollments to Chinese institutions. At the third FOCAC ministerial conference in 2006, then- president Hu Jintao announced that China would increase scholarships for African students from 2,000 to 4,000 before 2009. The FOCAC-initiated African Talents Program [19], announced in 2012, sought to train 30,000 African professionals in China between 2013 and 2015, and provided students with 18,000 government scholarships. In late 2015, at the sixth FOCAC ministerial conference in Johannesburg, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced [20] plans to further increase aid to post-secondary African students, with 30,000 additional scholarships; 2,000 post-graduate and doctoral slots at top Chinese institutions, and short-term, sponsored, visits to China for 200 African scholars and 500 African youths.

China’s support for Africa’s tertiary education sector extends beyond FOCAC: In 2009, China’s MoE launched the “20+20 Cooperation Plan.” The program formulated one-to-one partnerships between 20 Chinese and 20 African higher education institutions in 17 African countries, and sought to promote capacity building and sustainable development in Africa itself. The most recent batch of Chinese universities selected for the project included several prestigious institutions, 10 of which are Project 211 [21] institutions, including Peking University, Jilin University, East China Normal University, and others. Some Chinese universities have since initiated African studies, including Peking University Center for Africa Studies, Zhejiang Normal University Center for African Education Studies, and Tianjin University of Technology and Education Center for African Vocational Education Studies. The 20+20 program is now an integral part of the UNESCO-China-Africa Tripartite Initiative on University Cooperation [22], which seeks to further these partnerships as part of an effort to further build sector capacity and support a cadre of highly educated African citizens comfortable working in China and their home countries. The country also promised to provide USD $2 million annually under the framework of the UNESCO trust fund to support education development programs, in particular higher education, in Africa. Additional scholarship opportunities for African students to study in China have expanded dramatically since FOCAC shifted its focus to higher education. In August 2016, for instance, eight Chinese universities agreed to reserve slots for 1,000 Ghanaian [23] students annually. Cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Chongqing, and several higher education institutions have established regional and institutional scholarships for African students.

The Employment Advantage: Chinese Language Skills

The ability to speak Chinese is one key to success in tight African job markets, where both unemployment and underemployment can be staggeringly high [25]. The China-based Global Times [26] notes that Chinese infrastructure investments have created more than 600,000 jobs across the continent, creating “an obvious incentive for students eager to … give themselves a leg-up in what they hope will be a booming transnational industry.”

China has invested in supporting other post-secondary vocational training across Africa. In particular, the Chinese government has helped to establish a number of regional vocational education centers and colleges for vocational training [27] in Africa. Some of the most visible projects include the Ethio-China Polytechnic in Addis Ababa and the University of Science and Technology in Malawi. African vocational students have also begun to attend technical colleges in China. These colleges, notes the Global Times [26], “have seen a steady rise in foreign students from developing countries… [the] majority …from countries in Africa, like Egypt and Rwanda.. as part of [a] push to increase investment in the region. “[Beijing Information Technology College], for instance,” continues the paper, “has more than tripled its number of foreign students since it was first certified to admit them in 2012 from 20 to a new class of 60 each year…Likewise, Jinhua Polytechnic in Zhejiang Province had only three foreign students when it opened up its admissions to foreign applicants in 2007 – today it admits 40 each year.”

One reported advantage these students have is not just technical skills, but a working knowledge of Chinese language and culture. Across Africa, a growing number of Confucius Institutes similarly seek to fill a demand [28] among job seekers for Chinese language skills and cultural norms. These Chinese government-supported institutes are run in partnership with local colleges or universities around the world. As of 2015 [29], China had established 46 Confucius Institutes in in 32 African countries. According to Hanban [30] (the Confucius Institute Headquarters), China plans to increase the number of Confucius Institutes in Africa to 100 before 2020.

Future Outlook

Whether or not these higher education investments will continue to grow remains a matter of uncertainty [31]. On the one hand, China’s Africa-focused higher education outreach complements its domestic higher education agenda. As part of the National Plan for Medium and Long-term Education Reform and Development 2010-2020 [32], the Chinese government proposed an ambitious internationalization target: recruiting 500,000 foreign students by 2020, with 150,000 of them in degree programs. By 2015, the country had made significant progress against those goals, hosting some 397,635 foreign students [13].non-degree courses [33], mainly in language and cultural programs. Only a third of the total are enrolled in university degree courses. China’s Ministry of Education reports that African students are enrolled in both long-term and short-term study in China account for 12.5 percent of the country’s total foreign student population.[6]Numbers from China’s Ministry of Education may appear inflated in comparison to those provide by other sources such as UNESCO or the Institute for International Education. This is due to a number of factors, including data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.).

Scholarships play a big role in this influx of students: Between 2010 and 2014, a reported 33,866 Chinese government scholarships [18] were distributed to African students, and the government certainly seems poised to continue the escalation in funding that has occurred over the last decade. At the third FOCAC ministerial conference in 2006, then- president Hu Jintao announced that China would increase scholarships for African students from 2,000 to 4,000 before 2009. The FOCAC-initiated African Talents Program [19], announced in 2012, sought to train 30,000 African professionals in China between 2013 and 2015, and provided students with 18,000 government scholarships. And in late 2015, at the sixth FOCAC ministerial conference in Johannesburg, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced [20] plans to further increase aid to post-secondary African students, with 30,000 additional scholarships; 2,000 post-graduate and doctoral slots at top Chinese institutions, and short-term sponsorships for 200 African scholars and 500 African youths to visit China.

Stipend levels for students have also increased substantially. The Geneva based Network for International Policies and Cooperation in Education and Training (NORRAG) [34] reports that, as of 2015, stipends for multiple categories of students – undergraduate and Chinese language students, masters’ degree students, PhD candidates, and visiting scholars between 75 and 78.57 percent. In other words, all signs point to increased support for African students seeking higher education in China.

And yet, the Sino-African higher education relationship is marked by a fundamental disequilibrium: It is a “one-to-many” relationship, with China as the one, and Africa’s 54 nations as the many. This imbalance mirrors Africa’s broader position vis-à-vis China. China is, and has been, Africa’s chief trading partner since 2009, when the value of Sino-African trades outstripped those of the U.S. and Africa. Africa, however, is a minor trading partner for China, especially as compared to European Union, the U.S., and Asian players such as Hong Kong, Japan, and the ASEAN nations. Between aid and commercial investment, China contributes a substantial amount to African nations. In March 2013, President Xi Jinping promised USD $20 billion in investments between 2012 and 2015, and amount that he upped to USD $30 billion at the last FOCAC conference. However, from the Chinese perspective, the numbers remain relatively small, especially when viewed as a percentage of overall global investments.

Similarly, overall Africa policy remains a low priority issue for China, handled by “working-level agencies” once broad policy agendas are set. China Analyst John L. Thornton [35] speculates that the seeming disconnect between Africa’s rising investment in the region and its lack of coordinated policy can be explained fairly simply: Africa is important to China across a number of dimensions – ranging from economic, to the political, to the ideological – but also somewhat peripheral. African nations do not, collectively or singly, wield either the geopolitical clout that a country like America does nor the proximate regional threat that nations like Taiwan or Japan do. Moreover, a little Chinese investment goes a long way in impoverished Africa. As Thornton notes, a 2012 USD $3 billion loan to Ghana represented “almost 10 percent of Ghana’s annual GDP.” A 2008 USD $6 billion loan to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, meanwhile, represented more than half of the country’s recorded GDP.[7]Africa in China’s Foreign Policy, John L. Thornton, pp. 15-16Investment in the higher education sector thus makes sense at a very pragmatic level: It helps shore up African nations’ support in all important international forums such as the U.N., and helps to stabilize African economies so that Africa can serve as a viable export market for low-cost goods. Per this analysis, the strategy also provides, almost as a side benefit, a forum for building support for China’s political ideologies and approaches. Moreover, educational investments are low cost, and relatively low risk. They also create a halo effect of good will.

However, the scope of demand for post-secondary education in Africa is yawning: The continent already has the world’s fastest-growing university-aged cohort, with growth is expected to double from 2015 to 2050. China’s educational aid is insufficient to unlock the significant potential of Africa’s growing youth population. Thus, for all its growth the Sino-African educational relationship is one of the many needed to address the myriad needs of wave after wave of African students looking abroad for institutions and countries ready to support their higher education ambitions.

References

| ↑1 | Kritz, M. M. (2015), International Student Mobility and Tertiary Education Capacity in Africa. International Mirgation, Volume 53, Issue 1 February 2015, pp. 29–49 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Data from UNESCO’s Institute of Statistics, accessed in February 2017. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute for International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent. In some cases, organizations may report substantially different numbers of inbound or outbound international students from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. |

| ↑3 | Data from China’s Ministry of Education, accessed in February 2017. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute for International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. |

| ↑4, ↑7 | Africa in China’s Foreign Policy, John L. Thornton, pp. 15-16 |

| non-degree courses [33], mainly in language and cultural programs. Only a third of the total are enrolled in university degree courses. | |

| ↑6 | Numbers from China’s Ministry of Education may appear inflated in comparison to those provide by other sources such as UNESCO or the Institute for International Education. This is due to a number of factors, including data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). |