Kevin Kamal, Senior Manager, Client Relations, Canada, with WES Staff

This article describes current trends in education and international student mobility in Türkiye. It includes an overview of the education system, a survey of recent changes and reforms, and a guide to educational institutions and qualifications. It is adapted from an earlier version by Nick Clark, and Ari Mihael, and has been updated to reflect the most current available information.

Introduction: A History of Instability

Located at the crossroads of Europe and the Middle East, Türkiye has long been poised to reclaim its historic status as a significant global power. With the 18th largest economy in the world and a relatively young and growing population of 78.7 million people (2015, World Bank estimate [1]), it is also one of the world’s most powerful Muslim nations. In 2009, geopolitical writer George Friedman’s predicted that it would become the Middle East’s dominant regional country in his best-selling book “The Next 100 Years”[1]Friedman, George. 2009. The Next 100 Years: A Forecast for the 21st Century, New York. However, both domestic and regional conflicts slow down the realization of Türkiye’s full economic and political potential, both in terms of its geopolitical stature, and progress in key domestic sectors, including education.

Domestic Instability: Coups and Civil War

In its modern history, Türkiye has seen its share of political crises and military coups. Most of these events had a significant impact on education. A successful secular military coup in 1980, for instance, led to a purge of the university sector, and a broad restructuring of the education system.

In 2016, the country experienced yet another military coup attempt. In its wake, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan launched a widespread rollback of academic and other liberties, systematically purging civic institutions of political opponents and critics. In the higher education sector alone, some 5,000 academics, including deans and professors were almost immediately affected [2] by mass firings. At the elementary and secondary levels, an estimated 28,000 public school teachers [3] lost their positions. The fallout of these events has had ramifications for Türkiye’s international relations as well: The parliament of the European Union in late 2016 voted in favor of suspending talks with Türkiye on European Union membership, a goal Türkiye has been pursuing since 2004.

That Erdogan targeted the education sector is no surprise: Education has long served as a battleground between Türkiye’s secular factions, backed by Türkiye’s army, and conservative religious factions, which form the bedrock of the ruling Islamist “Justice and Development Party” (AKP). When the AKP first rose to power in 2002, education became a focal point for reform. The changes that ensued have had both positive and negative ramifications. On the plus side, a 2012 extension of mandatory education from grade 8 to grade 12 significantly increased upper-secondary school enrollments, and public spending on education increased substantially, as did higher education enrollments: Between 2002 and 2013, the tertiary gross enrollment jumped from 26 percent to 79 percent, as reported by the World Bank [4]. On the other hand, the reforms have also increased attendance at religious schools, in many cases due to involuntary tracking of students after only four years of formal schooling—a trend that has alarmed observers both within Türkiye and internationally.

Other domestic situations also have potential implications for Türkiye’s education system. The conflict with the Kurdish minority in southeastern Türkiye, which escalated into intermittent civil war since 1978, for instance, could potentially lead to a devolution of the education system, since the right to independently govern education is among the demands of Kurdish nationalists.

Regional Instability: The Impact of the Syrian Conflict

Turmoil in neighboring countries has likewise put pressure on Türkiye’s education system. Of particular note is the crisis in Syria. An estimated 2.85 million [5] Syrian refugees have flooded into Türkiye in the wake of the Syrian civil war and the country’s collapse. [See related article: The Importance of Higher Education for Syrian Refugees [6]]

Türkiye’s Ministry of National Education estimates that, in 2016, some 491,896 Syrian refugee children were attending Turkish primary and secondary schools. To accommodate their integration, the Turkish government is presently training more than 19,000 additional teachers in collaboration with UNICEF. Thousands of college-aged Syrian refugees are currently enrolled [7] in Türkiye’s higher education institutions. With many refugees likely to remain in Türkiye even after the war in Syria ends, the success or failure of efforts to integrate them will have a significant long-term impact on Turkish society.

The Gateway to the World: Inbound and Outbound Mobility Trends

Outbound Mobility

Türkiye has a pedigree as a gateway for “intellectual cross-fertilization” between Asian and European cultures—and as a locus of higher education—stemming as far back as the Ottoman Empire. Higher Education in Turkey. [9] Mizikaci, F., UNESCO, 2006. More recently, however, its higher education sector has suffered both capacity [10]and quality constraints. These and other underlying factors such as large youth cohorts and high unemployment rates [11] among university graduates, have spurred Turkish students to travel abroad for higher education in significant numbers. A 2013 British Council survey of more than 4,800 Turkish students [12] found that 96 percent wanted to study abroad in order to improve employment prospects. However, that ambition has not fueled increases in outbound numbers in recent years. In fact, according to data from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS [13]), the overall number of Turkish students seeking degrees abroad actually fell by almost 14 percent between 2010 and 2015, from 51,892 to 44,652.[2]This article includes international student data reported by multiple agencies. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies.

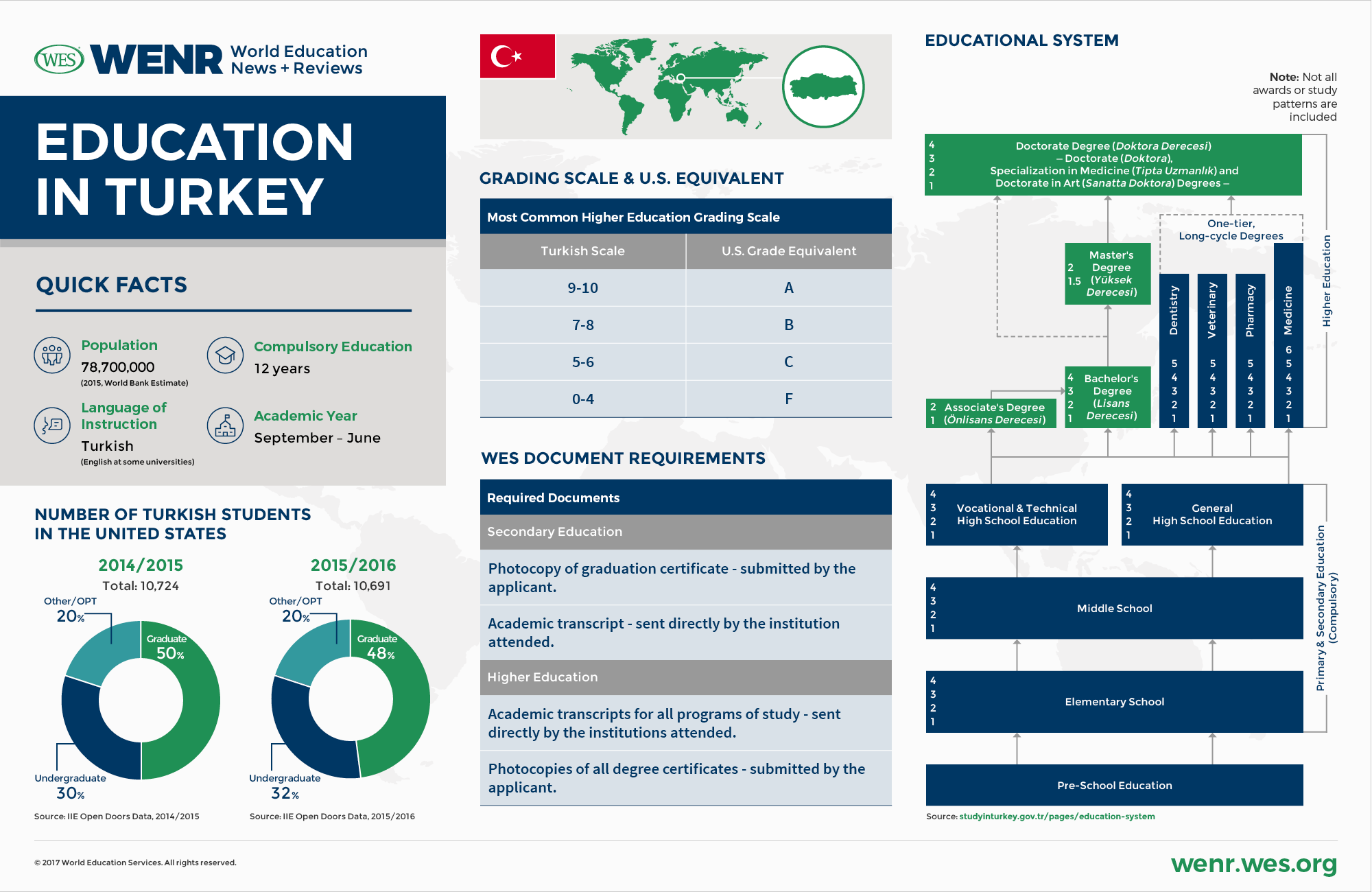

The United States is currently Turkish students’ number one choice for study abroad, but enrollments in U.S. higher education institutions have fluctuated for at least 18 years. According to the Institute of International Education Open Doors data [14], “after increasing from in the late 1990s,” some 9,397 Turkish students were enrolled at U.S. institutions by the end of the decade. IIE also notes that “Türkiye joined the list of top ten places of origin in 2000/01 and remained in tenth place, until it was displaced in 2012/13 after four consecutive years of decline…The number of Turkish students … fluctuated between 10,000 and 12,000 students [from] 2001/02 to 2013/14.”

Those fluctuations have continued. Enrollments peaked at 12,474 in 2010/11, and drifted to 10,691 in 2015/16, when Türkiye was the U.S.’s 13th largest source country for international students. This drop is likely due to several factors, including both diminishing international mobility among Turkish degree-seeking students overall, and enrollment gains by countries other than the U.S. Canada, for instance, saw its Turkish enrollments grow by more than 80 percent between 2006 and 2015.http://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/052642bb-3fd9-4828-b608-c81dff7e539c?_ga=1.129598988.1449264574.1482960422 [15], accessed March 2017.

Analysis by the British Council suggests that new markets may be gaining traction among Turkish students. The Council predicted in 2014 [16] that over the next decade, the total number of Turkish postgraduate students would rise in Australia, Canada, Germany, and the U.K., and decrease in the U.S., albeit slightly. Those outbound Turkish students not enrolled in the U.S. have most often sought out European campuses, with top countries including, as of 2014, Germany, Bulgaria, the UK, Austria, Azerbaijan, Bosnia Hercegovina, France, Ukraine, and Italy.

Despite declines, the U.S. nonetheless remains Turkish students’ most likely destination, with enrollments heavily weighted toward graduate programs. In 2015/16 [17], for instance, graduate programs accounted for 47.9 percent of Turkish enrollments, compared to 31.7 percent in undergraduate programs. Some 12.9 percent were in the U.S. on Optional Practical Training [18] visas.

Germany is, as of 2017, the second most popular Turkish study destination after the U.S., with high and relatively steady enrollment numbers in recent years. Following Germany’s post-war “economic miracle [19],” large numbers of Turkish guest workers and immigrants started to migrate to Germany beginning in the early 1960s. Due to this influx, Turks currently constitute the largest ethnic minority in Germany. This migration pattern is reflected in university enrollments. Some 27,951 permanent residents of Turkish origin [20] were studying at German universities in 2015. That same year, 6,785 Turkish international students [21] were enrolled on German campuses. These students reportedly view to Germany as a low-cost study destination; they typically enroll [22] in business and engineering programs, or technical disciplines.

Inbound Student Mobility

Despite some of the challenges faced by its higher education sector, Türkiye has become an increasingly important destination for internationally mobile students in recent years, particularly from the larger Middle Eastern region and Central Asia. Efforts by the Turkish government to promote internationalization, strong economic growth, low visa hurdles [23] for neighboring countries, as well as Türkiye’s strategic location as Europe’s gateway to Asia have made the country a progressively more attractive higher education destination.

The Turkish government has in recent years pursued an aggressive internationalization strategy and aims to host more than 200,000 international students by 2023, according to [24] Serdar Gündoğan, head of the Turkish Prime Ministry’s International Students Department. To this end, the AKP government in 2014 allocated USD $96 million to international student scholarship programs—the highest amount ever. International student quotas set by the government, likewise, have been expanded to accommodate larger student numbers, and universities have been given greater freedom in admitting international students, while private university foundations are reportedly recruiting more aggressively abroad. Türkiye’s Council of Higher Education, through its “Study in Türkiye” [25] website, is actively branding and promoting Turkish universities to prospective international students.

In addition to increased marketing and scholarship funding, Türkiye’s government is also supporting partnerships between Turkish and international universities, and has recently promoted [26] Türkiye as a study destination in new markets like Vietnam.

According to data provided by the “Turkish Universities Promotion Agency”, the total number of international students in Türkiye, including degree and non-degree-seeking students, grew by 77 percent [27] between 2002 and 2014, from 31,000 to 54,000. (International enrollment numbers provided by UIS, which do not include non-degree students, reported 48,183 international students in Türkiye in 2014.)

The increased use of English at Turkish universities has reportedly been a draw for some international students, although cultural and linguistic ties with Turkic students from Central Asia and the Caucasus, combined with relatively low tuition costs, continue to be the biggest lure for international students in Türkiye. Indeed, most international students in Türkiye come from neighboring countries, especially those with religious, linguistic, and cultural ties. According to the UIS statistics, Türkiye hosted 6,861 students from Turkmenistan, 6,703 from Azerbaijan, and 4,266 from Iran in 2014. Türkiye also recently became the second most popular study destination for Iranian students abroad, after the U.S. (Current attempts by the U.S. government to—at least temporarily—stop Iranians from obtaining visas to the U.S., have the potential to further increase [28] Iranian student enrollments in Türkiye.)

Other Central Asian countries like Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan, and countries from other regions, including Greece, Russia, and Nigeria are among the 93 countries that reportedly [27]send international students, most of them at the undergraduate level, to Turkish universities. Istanbul University, Ankara University, and Marmara University enroll some of the highest numbers of these students.

As of 2017, Great Britain’s impending exit from the European Union, its increased hostility to foreign students, and rising global uncertainty about the U.S.’S willingness to admit students from several Muslim-majority countries may pose an opportunity for international enrollment growth in Türkiye. However, Türkiye’s current crackdown on academic freedoms poses steep barriers to growth, as does its rocky relationship with the EU. At stake are not only student flows, but international research cooperation, financial aid, and other issues central to the quality and reputation of the Turkish education system at large.

Türkiye’s Education System in Brief

Regulatory Structure: Elementary and Secondary Education

Türkiye has seven regions, 81 provinces, and a highly centralized system of government. Accordingly, most education policies are steered by the national government in Ankara. The national Ministry of National Education [29] sets policies and oversees the administration of all stages and types of pre-tertiary education. The head of the ministry appoints Directorates of National Education to work at the provincial level. These directorates work under the direction of provincial governors. Schools and other local actors have little autonomy.

Regulatory Structure: Public Higher Education

In 1981, the then-ruling military government ushered in a comprehensive higher education law. Since then, planning and coordination of public higher education institutions has fallen under the purview of the Council of Higher Education ( Yükseköğretim Kurulu or YÖK [30]). The council is responsible for planning, coordination, and governance of the higher education system. It sets university budgets, institutional enrollment and admission caps, and core curriculum guidelines. It also appoints faculty heads. YÖK is technically designed to be an independent institution reporting to a non-partisan and non-governmental national board of trustees; critics contend [31], however, that the council is not independent and has been utilized by governments to shape education policies that reflect partisan political agendas. YÖK’s full reach was on display following the failed 2016 coup, when it asked 1,577 university deans (reportedly every dean in the country) to resign [32] “for the sake of democracy.”

As of 2014, Türkiye had 104 public universities, with a total estimated enrollment of 5.5 million students. Per YÖK [33], about 61 percent were enrolled in face-to-face courses, the rest were pursuing degrees via distance education.

Regulatory Structure: Private or Foundation (Awqaf) Universities

After being banned in the early 1970s, private universities were again permitted in Türkiye’s neo-liberal economic era of the 1980s. Since then, private institutions have been allowed to operate, on a non-profit basis and under governmental supervision. The curricula of these so-called “foundation (Awqaf) universities” must be approved by the YÖK. The first foundation university, Bilkent University, opened in 1984 and has provided a successful Turkish model for private higher education. As of 2014, Türkiye had 72 foundation universities [34], which enrolled a total of 351,000 students, representing 6.4 percent [35] of all university students in Türkiye.https://www.academia.edu/9719097/Foundation_Awqaf_Universities_in_Turkey-_Past_Present_and_Future [36], accessed March 2017.

Foundation universities can be either research institutions or pure teaching institutions. The governance of these universities differs from that of public institutions in that they operate under less stringent government restrictions. Whereas the deans of public universities are directly appointed by the government, the deans of foundation universities are chosen by boards of trustees. (The appointment of rectors does require the consent of the YÖK.)

Foundation universities charge very high tuition fees (up to USD $20,000 per year). Compared to public institutions, which are mostly government-funded and charge just a few hundred U.S. dollars in annual fees, they also pay higher salaries to their faculty. Some 40 percent of their students are said to currently receive scholarships. Proponents of private education argue that foundation universities provide better education than public universities and should be considered a role model for other countries in the Middle East [35]. Classes are often taught in English, and the teaching style tends to be less hierarchical, allowing for more open interactions between students and professors. Critics, on the other hand, maintain that these institutions, deepen social divisions by creating an elitist from of education [37] only accessible to wealthy segments of the society.

Demographic Trends and Educational Performance Indicators

Demographically, Türkiye is an increasingly young and affluent country and, as such, has tremendous need for education. The size of Türkiye’s middle-class increased from 18 percent to 41 percent between 1993 and 2010 [38]. The country also has one of the youngest populations in the OECD, with the second-highest share [39] of people under the age of 15 (24.3 percent) after Mexico (28 percent) in 2014.

In absolute terms Türkiye has progressed considerably on many standard education indicators in recent years, but in relative terms it continues to lag behind most other OECD countries. In elementary and junior secondary education, enrollment levels are relatively high, with 95 percent of children [40] aged 5-14 attending school in 2013. This compares to an OECD average of 98 percent. At more advanced attainment levels, however, Türkiye does not fare as well. The percentage of 25- to 64-year-olds without any upper-secondary education was 63 percent in 2015—up from 72 percent in 2005, but still the second-highest percentage in the OECD. (The overall average in the OECD was 23 percent in 2015.)http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/9616041e.pdf?expires=1489694604&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=8AA18732983A1257B13D2FD2608F925C [41], 43, accessed March 2017. The 2012 extension of compulsory education until grade 12 (discussed below) is expected to increase upper secondary-level enrollments going forward.

Tertiary-level attainment levels are also relatively low. In 2015, only 18 percent of 25-64 olds had any tertiary-level education (up from 10 percent in 2005) compared to 35 percent in the OECD.http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/9616041e.pdf?expires=1489694604&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=8AA18732983A1257B13D2FD2608F925C [41], 43, accessed March 2017.

These—by OECD standards—low averages are notwithstanding tremendous gains in absolute terms: The total number of graduates from tertiary education programs, for example, increased by 170 percent between 2005 and 2014, from 271,841 in 2005 to 573,159 in 2010 and 733,237 in 2014, according to UIS data [42]. Increased participation rates in higher education have had positive effects on income levels in Türkiye. In 2012, adults with tertiary education were much more likely to be employed than their less-educated peers, and earned an average 91 percent more than adults with upper secondary education, compared to 59 percent in the OECD.

Education Spending

Education is presently the biggest item on the Turkish government budget, and the Turkish Statistical Agency reports [43] that direct and indirect expenditures on education increased by 54 percent between 2011 and 2014, from 73.6 billion Turkish liras (20.3 USD $billion) to 113.6 billion liras (USD $31.4 billion). UIS data [44], likewise, suggests that the percentage of education spending as part of the overall Turkish budget increased by one third between 2006 and 2013, from 8.5 percent to 12.4 percent.

In terms of growth rates at least, Türkiye presently outpaces richer OECD countries: The rate of increase in public expenditures for education is well above OECD average in many areas, according to the OECD’s most recent “Education at a Glance [45]” report. Those increases notwithstanding, OECD [46] reports indicate that the 4.6 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) that Türkiye spent on education in 2013 was less than the OECD average.

The Structure of Türkiye’s Education System

Compulsory Education: Elementary, Lower Secondary, and Upper Secondary — From “8+3” to “8+4” to “4+4+4”

Compulsory education in Türkiye begins at age 5, and, as of 2012, lasts through 12th grade. It is free of charge. The education system at this level falls under the purview of the Ministry of National Education (Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı), which sets the school curricula, and prepares and approves textbooks and teaching aids.

Until the 2012/13 school year, the Turkish school system was based on a 1997 law, which mandated eight years of compulsory elementary education, followed by three years of optional secondary school (8+3 system). In 2005, an additional year was added to the secondary school option, creating an 8+4 system.

In 2012, compulsory education was extended to 12 years, and split into three levels of four years each (4+4+4 system). Pupils now complete four years of elementary education before entering middle school in the fifth grade. Four years of middle school are followed by four additional years at the upper-secondary level.

4+4+4: The Ensuing Controversy

The 2012 reform reversed efforts of the secularist government [47] of Mesut Yılmaz to stem a rise of enrollments in religious schools by closing religious vocational imam hatip middle schools and making pupils stay in general elementary schools for eight years. Prior to 1997, pupils undertook five years of elementary education followed by three years of lower-secondary education in middle schools, including religiously oriented imam hatip schools. (See sidebar, below.)

The 4+4+4 reforms introduced entrance examinations for all secondary schools except for vocational schools. Since the number of seats at general academic schools is limited, this change will steer a significant number of pupils towards religious schools, and turn these schools from a selective option into a more central part of Türkiye’s education system [48].

As the Swedish scholar Svante E. Cornell has noted, in “… August 2013, over 1,112,000 students took the placement test for 363,000 slots in regular, academic high schools. Those that did not make the cut had to choose between secular vocational schools, imam-hatip schools, and another set of schools called “multi-program high schools.” But the latter are only available in remote areas, and do not even exist in the entire province of Istanbul. In other words, [many] parents and students were forced to choose between vocational schools and religious schools.” The effective result of the reforms is thus that many Turkish children are forced onto a narrow vocational track at the very young age of 9 with only four years of basic general schooling.

Other concerns have focused on the negative impact the reform [49] could have on school enrollments, especially among girls. Under the new law, parents are allowed to home school their children after the first four years of elementary education. The concern is that parents, particularly in rural parts of the country, might use the home-school provision as a loophole to pull their daughters out of school after just four years.

Imam Hatip Schools: 4+4+4 Reforms Drive a Wave of Enrollments in Religious Schools

Imam hatip schools are institutions devoted to the training of Muslim clergy (imams and preachers). The role of these institutions in Türkiye’s education system is a hotly debated topic between proponents arguing for religious freedom and secularists who oppose a central role for these schools in Turkish schooling, based on the grounds that Türkiye is constitutionally a secular state.

In past decades, the role of imam hatip schools was limited, especially at the middle school level. Specifically, the extension of elementary schooling to eight years by a secularist government in 1997 prevented pupils from enrolling in religious schools until grade 9 and resulted in a decrease in enrollments in these schools.

Türkiye’s 2012 “4+4+4” reform reversed these changes. Specifically, the reform created a need for new middle schools—a void that is partially being filled by a disproportionately high number of new imam hatips. According to some reports, the number of imam-hatip schools increased by 73 percent between 2010 and 2014 compared to 23 percent and 57 percent increases in the number of technical and general Anatolian high schools respectively. [7]Hurriyet Daily News, August 28, 2014, Türkiye’s education row deepens as thousands placed in religious schools ‘against their will’ http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkeys-education-row-deepens-as-thousands-placed-in-religious-schools-against-their-will.aspx?PageID=238&NID=71036&NewsCatID=341. Accessed March 2017.

Türkiye’s AKP-led government contends that the new shorter education cycles give pupils greater flexibility in choosing between different types of schools. The government has framed the 4+4+4 reforms primarily as a measure to extend mandatory schooling to twelve years. Critics charge that it is a politically motivated attempt to advance the Islamization of education. In 2012, for instance, Türkiye-based journalist Andrew Finkel, penned a New York Times column [50], arguing that “…the real purpose of the legislation may be less to keep children in school longer than to let them pursue intensive religious education younger.” Whatever the actual intent, enrollments in imam hatips, like the numbers of schools themselves, have risen more than eight-fold since 2002, when the conservative AKP came to power, from only 65,534 pupils, or about 2.6 percent of students, to 546,443 pupils in 2014 (9.6 percent of students), according to Ministry of Education data quoted by Turkish scholar Bekir S. Gur [51].

Other critics contend that the new 4+4+4 system will prematurely limit children’s educational options. Batuhan Aydagül, director of the Education Reform Initiative at Istanbul’s Sabancı University, for instance, argues that the “… government is limiting the supply of non-religious schools and increasing the supply of religious ones (…) Either explicitly or unknowingly, they are creating a situation where some students will have to go to these schools regardless of their will.”http://www.newsweek.com/2014/12/26/erdogan-launches-sunni-islamist-revival-turkish-schools-292237.html, accessed March 2017 [52].

Upper-Secondary Education: Enrollments and Admission

Upon completion of middle school at the end of grade 8, students can study at general, technical, or vocational upper-secondary or high schools (the Turkish name for high school is “Lise”). This upper-secondary education lasts four years (grades 9 through 12.) According to UIS data [44], the number of students enrolled at the upper-secondary level increased from 3.69 million in 2010 to 4.99 million in 2013, when the first cohort of students enrolled under new laws making their attendance compulsory. Further enrollment increases are expected going forward.

Admission to general schools is based on the “Transition from Primary to Secondary Education” (TEOG) examination at the end of grade 8. Students are tested in subjects like Turkish, mathematics, religion and ethics, science, history and Kemalism [53] (Atatürkism), and foreign languages.

Students who do not earn sufficiently high scores to get into their school of choice are assigned to schools nearest to their residence, including vocational schools, which generally do not require the TEOG exam for admission. In recent years, the selection process at the end of grade 8 has resulted in large numbers of students being involuntarily assigned [54] to vocational imam hatip schools. (See sidebar, above.)

Upper-Secondary Education: Vocational and Technical Streams

Four years in length, technical and vocational high school programs can be divided into four main types: industrial and technical; commerce, tourism, and communication; social services; and religious services.

Graduates of the technical branch are awarded the Teknik Lise Diplomasi (Secondary Technical School Diploma) or Devlet Teknik Lisesi Diploması (State Technical High School Diploma). Graduates of the vocational branch are awarded the Meslek Lise Diplomasi (Secondary Vocational School Diploma) or Devlet Meslek Lisesi Diploması (State Vocational High School Diploma). The diplomas in both streams grant access to university entrance examinations (although most students typically continue to study at higher vocational schools).

Vocational schools include a wide variety of specializations, ranging from electronics to chemistry, automotive technology, construction, public health schools, religion, agriculture, and more. Special girls’ vocational schools are dedicated to the study of home economics and the like.

The curriculum at technical and vocational high schools typically incorporates practical skills training in addition to the general academic core curriculum. Graduates from both types of schools can apply for admission to post-secondary higher vocational schools or can transition into the workforce upon graduation.

Upper-Secondary Education: General Academic Programs

There are several different types of schools in the general academic high school stream. These include foreign language high schools (Yabanci Dil Agirlikli Lise), science high schools (Fen Lisesi), and so-called Anatolian high schools (Anadolu Lisesi), which are selective schools that use a foreign language medium, typically English, for instruction in some subjects. All of these schools are academically focused and prepare students for higher education.

The curriculum in general academic programs is common to all students in the first year of study and includes biology, chemistry, foreign language, geography, health, history, mathematics, military science, philosophy, physical education, physics, religious education and ethics, and Turkish language and literature. In grade 10, students declare a concentration in one of several different streams such as natural sciences, literature and mathematics, social sciences, art, foreign languages, and mathematics.

In grades 10, 11, and 12, all students attend common courses, but the bulk of time is devoted to elective concentration subjects. Overall, students spend a minimum of 30 hours a week in the classroom, regardless of concentration. Programs conclude with final high school examinations.

After four years of study, graduates are awarded the Lise Diplomasi (Secondary School Diploma), which gives access to the university entrance examinations.

Türkiye’s Test Scores: A Poor International Showing

The OECD’s “Programme for International Student Assessment” (PISA) is a test used to measure the comparative quality of secondary education systems. In 2015, 540,000 15-year-olds from 72 OECD and OECD partner countries sat for assessments in science, mathematics, and reading skills. As in previous PISA studies, the test results were not kind to Türkiye and indicated continued weaknesses in Turkish schooling. Turkish students performed worse than in the last PISA test in 2012, and scored second to last among the 35 OECD countries—only Mexican students scored lower within the OECD. On the upside, Türkiye scored above the OECD average in social equality indicators (impact of social status on performance), and gender equity (impact of gender on performance).

Grading Scale

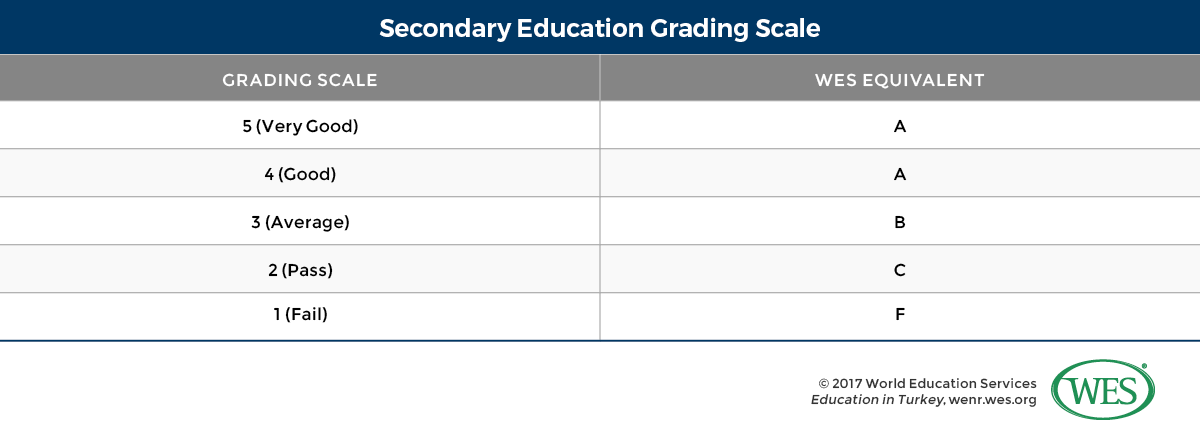

At the secondary level, most schools follow the ministry-approved 1-5 grading scale. Grading in Turkish secondary education is somewhat stringent, and grades tend to cluster in the twos and threes. Given the grading distribution common to Turkish secondary education, WES considers both grades ‘4’ and ‘5’ as equivalent to a U.S. ‘A’ grade. The ‘5’ grade is not commonly awarded in Türkiye.

Higher Education

Admissions

Admission to undergraduate programs at Turkish universities is based on students’ grade point averages from secondary school and their scores on the two-stage university entrance exams. Typically, university entry is reserved for students who graduate from the general academic secondary branch. Graduates of technical and vocational schools typically pursue further studies at technical institutes.

Students who obtain a Lise Diplomasi, Meslek Lise Diploması, or Teknik Lise Diploması are eligible to sit for a centralized, two-stage university entrance examination administered by the Student Selection and Placement Center [56] (ÖSYM) and supervised by the Turkish Council of Higher Education (YÖK).

- Students first sit for the so-called “Transition to Higher Education Examination” (Yuksek Ögretime Gecis Sinavi, YGS), usually conducted in April or March. The YGS is a multiple-choice exam in a number of standard subjects including Turkish, mathematics, social sciences, and science.

- Students with sufficiently high scores are then allowed to take the Undergraduate Placement Examination (Lisans Yerlestirme Sinavi, LYS) in June, which is another standardized exam in a similar range of subjects.

The number of Turkish students who sit for the admissions examinations has grown considerably in recent years and exceeds the number of available seats at Turkish universities. In March of 2017 [57], more than 2.2 million students sat for the YGS examination compared to 1.85 students in 2013 [58], an increase of almost 19 percent. Placement in university programs is competitive and based on demand and test performance. Students who pass only the YGS or do not wish to pursue university studies can obtain admission to non-university associate degree programs, but not to bachelor’s degree programs at universities.

Higher Education: Enrollment Trends

Total enrollments in Türkiye’s tertiary education system have more than doubled in recent years, from 2.1 million students in 2005 to 5.5 million students in 2014, as per the statistics provided by UIS [44]. According to the Council of Higher Education [34] (YÖK), approximately 1.7 million students were enrolled in associate degree programs in the 2013/2014 academic year, 3.4 million in bachelor’s degree programs, 262,752 in master’s degree programs, and 65,864 in doctoral programs. Overall tertiary graduation rates have increased in recent years as well: the gross graduation ratio in tertiary first-degree programs was 31.7 percent in 2014, compared to only 11.7 percent in 2005 (UIS).

A substantial number of Türkiye’s students (39 percent) were enrolled in distance education programs in 2013/14. First introduced in the 1980s to expand access to education in rural areas and advance the massification of education amid capacity shortages, distance education has today become a prominent feature of Türkiye’s education system. While many universities that provide distance education tend to focus [59] less on the delivery of degree programs than the provision of shorter programs in the life-long learning and adult education sectors, a limited number of universities offer a range of so-called “open education” associate and bachelor’s degree programs.

The public Anadolu University was the first of these institutions and is today the largest open education provider in the country. The other institutions with open education degree programs are Istanbul University and Atatürk University. Academic degrees earned in “open education” mode have the same legal standing as regular degrees, but may be regarded [59] less favorably than regular degrees on the labor market.

Gender Equity: Women in Türkiye’s Graduate Programs and in the Workforce

There is always a correlation between educational attainment and success in the labor market and salary level, hence self-sufficiency for women. Between 2008 and 2011, the percentage of Turkish women who were neither employed, nor in education or training (NEETs) was 50 percent — more than twice that of men, among whom 20 percent were neither employed nor in education or training.

“As in most other OECD countries, Türkiye displays a clear gender imbalance among tertiary graduates over their field of study,” noted the 2016 edition of Education at a Glance: OECD Indicators. “Women represent 27 percent of graduates in the field of engineering, manufacturing, and construction … and 50 percent of graduates in science, mathematics, and computing.” Although these rates compare favorably to OECD averages, highly educated women have a disproportionately hard time finding employment in Türkiye. “The employment rate among tertiary-educated adults is 58 percent for women and 76 percent for men,” reported the OECD. “Moreover, a woman with a tertiary degree earns only 84 percent of what a tertiary-educated man earns, although this gender gap is smaller than the OECD average of 73 percent.”

How women’s education attainment will change over time remains unclear. Graduation rates are increasing at some advanced levels and decreasing at others. Between 2012 and 2014, the number of women earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees grew by 22 percent and 26 percent respectively. At the doctoral level, it fell by 45 percent (UIS).

Higher Education: Institutional Types — Public, Private, and Other

As of 2014, Türkiye had 104 state universities and 72 private foundation universities, as well as a number of police and military academies, and eight self-standing post-secondary vocational institutes. (Other vocational institutes are housed within universities).

While enrollments at private universities are generally rising, overall tertiary enrollment in Türkiye continues to be predominantly concentrated in the public sector—only 6.6 percent of tertiary students were enrolled at private institutions in 2014 (UIS). A total of 360,670 students attended private foundation universities in the 2013/2014 academic year, according to YÖK. A large number of the (by Turkish standards) very expensive private foundation universities are located in Istanbul; most others are clustered around major population centers as well. Public universities have a much broader reach across the country’s seven regions.

Accreditation, Bologna, and YÖDEK

Both private and public universities in Türkiye are directly recognized and overseen by the Council of Higher Education (YÖK). Even though Türkiye signed the Bologna declarations in 2001, the country has so far been slow to adopt external program accreditation on a significant scale or implement other external quality assurance mechanisms, which are key concepts of the Bologna reforms. One of the exceptions to this was the establishment of the “Association for Evaluation and Accreditation of Engineering Programs” (MÜDEK [60]), a non-governmental accreditation agency for engineering programs.

According to the YÖK website [61], Türkiye has also adopted systematic internal quality assurance mechanisms for its universities and established an independent “Commission for Academic Assessment and Quality Improvement in Higher Education” (YÖDEK [62]) intended to license private accreditation agencies and advance external quality assurance. Little information on the work of YÖDEK was available as of writing. It also remains unclear how the government’s recent restrictions on academic autonomy will impact these reforms.

University Rankings: A Proxy for (Uncertain) Quality

In 2014, the online publication Al-Anfar Media ran an article titled “Turkish Delight: Rising in the University Rankings.” The article addressed Turkish universities’ increased prominence in global rankings, noting that four Turkish universities appeared in the top 200 of the 2014/15 Times Higher Education World University Ranking, up from just one in 2013/14. In the years since, however, Turkish universities have dropped again. No Turkish university made it into the top 200 of the 2016/17 THE ranking—the three highest-ranked universities were Koç University (251-300), Sabancı University (301-350), and Boğaziçi University (351-400), all of them private foundation universities. The highest-ranked universities in the 2016/17 Quacquarelli Symonds World University rankings were Bilkent University (411-420), Sabancı University (441-450), and Koç University (451-460).

Degree Programs

Türkiye has a U.S.-style three-cycle system, which includes a Bachelor’s degree, Master’s degree, and doctorate. In addition, the Turkish system also includes a two-year associate degree, which is mostly a non-university qualification in technical and vocational fields designed to prepare students for entry into the labor force.

Despite signing the Bologna declarations in 2001, Türkiye has maintained its four-year Bachelor’s degree rather than adopting the standard Bologna three-year first cycle degree. Türkiye has made other changes in order to comply with the Bologna process. In 2005, for instance, the Turkish government-mandated adoption of the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System [63] (ECTS) and Diploma Supplements, both of which are now increasingly used by Turkish universities.

The language of instruction at universities is Turkish, although some programs are taught in English, and very rarely, in German or French. English is the medium of instruction at a number of private universities, including Boğaziçi University, and Bilkent University. Turkish Degree certificates may be issued with either a Turkish or English degree name.

Universities can generally determine their own curricula and graduation requirements, but a number of compulsory subjects at public universities are determined by the Council of Higher Education (YÖK). At the undergraduate level, they include civic education; Ataturk’s principles and history of the Turkish revolution; language studies (foreign and Turkish); and art, music, or physical education. Undergraduate curricula tend to be specialized, with limited elective course options.

Associate Degree (Önlisans Diploması)

Associate degree programs are mostly offered at “schools for higher professional education” (meslek yüksek okulu) attached to universities or at independent post-secondary vocational institutes. Programs may include a practical training component, and are generally offered in applied fields intended to prepare students for employment.

They are two years in length and require a minimum of 64 Turkish credits or 120 ECTS for graduation. Some programs are offered at universities and may articulate into a four-year bachelor’s degree. Programs awarded by vocational schools typically do not give direct access to university study, but a so-called “vertical transfer examination”, centrally administered by the “Student Selection and Placement Center” (ÖSYM), does allow graduates from vocational schools to transfer into the third year of bachelor’s degree programs at many universities.

Bachelor Degrees (Lisans Diploması)

The standard Bachelor’s degree is conferred following four years of study, and typically requires the completion of a minimum of 128 Turkish credits (240 ECTS). Admission to universities is based on students’ high school grade average and the results from the centrally administered YGS-LYS examinations. Some universities may have additional entrance examinations.

Professional Degrees

Professional degrees in Türkiye are awarded upon completion of long, single-tier university programs entered directly after high school. Programs in engineering, dentistry, architecture, and veterinary medicine are five years in length (160 credits/300 ECTS). Medical programs are six years in length, including a clinical internship. Professional degree titles include the Dis Hekimligi Diploması (dentistry diploma), Eczacilik Lisans Diploması (pharmacy diploma), Tip Doktorlugu Diploması (doctor of medicine diploma), and Veteriner Hekim Diploması (veterinary medicine diploma). The final credentials are considered master’s-level qualifications in Türkiye, and may enable access to doctoral programs.

Specialization training in medicine lasts two to six years beyond the first professional degree, depending on the specialty, and concludes with the award of a specialist certificate (Uzmanlık Belgesi). Postgraduate specialist certificates are also awarded in other disciplines, such as pharmacy, dentistry, and veterinary science.

Master’s Degrees (Yüksek Lisans Diploması)

Admission to master’s programs is usually based on the grade point average obtained in the bachelor’s program, and successful passage of entrance examinations. Some graduate schools may also conduct interviews. There are two types of master’s programs: those with a final thesis and those without. The programs with a final thesis take two years (60 Turkish credits, 120 ECTS); those without take one and a half years to complete (45 Turkish credits, 90 ECTS).

In addition to the master’s degree, Turkish universities also award a postgraduate credential called Bilim Uzmanligi Diploması (specialist diploma in science). This program is only offered in selected fields, is usually two years in length, and is often considered a master’s-level qualification.

Doctor of Philosophy (Doktora Diploması)

Doctoral degrees in Türkiye are research degrees that require a master’s degree for admission (typically a master’s degree with thesis, although holders of non-thesis degrees may also be considered). Programs are offered in a variety of disciplines and entail the preparation of a dissertation in addition to a limited amount of compulsory coursework (a minimum of seven courses/21 credits). Programs most typically take four years to complete and conclude with the public defense of the doctoral thesis.

Teacher Education

Teachers at the preschool, elementary, and secondary levels are required to have a four-year bachelor’s degree in order to teach in Türkiye. Teacher training curricula incorporate specialization subjects, pedagogical subjects, practice teaching, and teacher certification. Students can earn either a bachelor’s degree in education or complete postgraduate training following a bachelor’s degree in a non-teaching discipline.

A one-year professional proficiency certificate (Öğretmenlik Formasyonu) entitles holders to teach English and selected subjects at the elementary and pre-school levels, whereas elementary and secondary school teachers in subjects like history, geography, mathematics, or physics are required to complete a master’s degree.

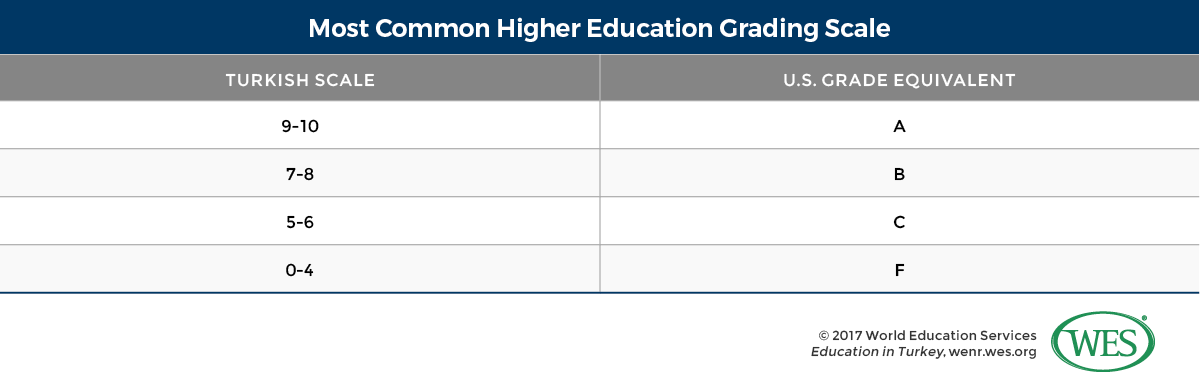

Higher Education Grading Scale

Grading scales may vary by institution. Some universities use a letter grading scale (AA, AB, etc.), but the most common scale runs from 0-10. Many private universities use a U.S.-based marking system (A-F), and a four-point GPA. Typically, public universities use the 0-10 grading scale. Grading at public universities tends to cluster in the ‘7’-‘8’ range, which is on par with clustering patterns in the U.S. around the ‘B’ grade.

WES Document Requirements

Higher Education (Lisans Diplomasi, Yüksek Lisans Diplomasi, Doktora Diplomasi, etc.)

- Academic transcripts – sent directly to WES by the institution attended.

- Degree certificates – submitted by the applicant.

- For completed programs, a European Diploma Supplement issued in English is preferred and will expedite the evaluation process.

- For completed doctoral programs, a letter confirming the awarding of the degree – sent directly to WES by the institution attended.

Secondary Education (Lise Diplomasi, Meslek Lise Diplomasi, etc.)

- Graduation certificate – submitted by the applicant.

- Academic transcripts – sent directly to WES by the institution attended.

In most cases, Turkish institutions will send academic documents to requesting institutions outside of Türkiye in a timely manner. The WES experience with Turkish universities is that documents will typically be sent within a week of the student requesting them. At both the secondary and university level, institutions will send documents directly. For an additional fee at many universities, students can request expedited service. In most cases, the Turkish student can arrange for the awarding institution to send an English version of the documents. Public universities, especially, are able to send official dual-language documents (one set in English, one set in Turkish) upon request and oftentimes they do this as common practice. An increasing number of private universities now do the same.

Sample Documents

Click here [65] for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Anadolu Lisesi Diplomasi (Anatolian High School Diploma)

- Hacettepe University –Bachelor of Science (Academic Transcript)

- Sabanci University – Bachelor of Arts

- Middle East Technical University – Bachelor of Industrial Design

- Marmara University – Yüksek Lisans (Master’s degree)

- Izmir University of Economics – Lisans Diplomasi (Bachelor of Science)

References

| ↑1 | Friedman, George. 2009. The Next 100 Years: A Forecast for the 21st Century, New York. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This article includes international student data reported by multiple agencies. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. |

| http://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/052642bb-3fd9-4828-b608-c81dff7e539c?_ga=1.129598988.1449264574.1482960422 [15], accessed March 2017. | |

| https://www.academia.edu/9719097/Foundation_Awqaf_Universities_in_Turkey-_Past_Present_and_Future [36], accessed March 2017. | |

| http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/9616041e.pdf?expires=1489694604&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=8AA18732983A1257B13D2FD2608F925C [41], 43, accessed March 2017. | |

| ↑7 | Hurriyet Daily News, August 28, 2014, Türkiye’s education row deepens as thousands placed in religious schools ‘against their will’ http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkeys-education-row-deepens-as-thousands-placed-in-religious-schools-against-their-will.aspx?PageID=238&NID=71036&NewsCatID=341. Accessed March 2017. |

| http://www.newsweek.com/2014/12/26/erdogan-launches-sunni-islamist-revival-turkish-schools-292237.html, accessed March 2017 [52]. |