Zhengrong Lu and Megha Roy, Research Associates, WES

In recent months, Canada has emerged as a likely go-to destination for highly skilled immigrants who might otherwise have ended up in other countries, in particular, the United States. World Education Services has a unique window on U.S.-Canadian immigration trends: We receive applications for credential evaluations from potential immigrants and students headed both north and south of the border. In recent months we, along with the rest of the world, have witnessed a spike in Canadian applications and a concurrent downward drift in U.S. numbers. It’s within that context that we recently evaluated the results of a survey of more than seven thousand WES applicants who applied for permanent Canadian residency as skilled workers [1] in 2016.

Our goal was to gain insight into the migration paths of those who come to Canada via a “second country” – a place other than their country of origin or their intended immigration destination – rather than a more traditional two-step immigration path. The questions we investigated were:

- What percentage of these applicants obtained an education or work experience in a second country?

- Where did these second-country immigrants come from?

- What are the characteristics of second country immigrants? For instance: What are their educational levels? What are their fields of study? How much work do they have in the field, prior to application?

What We Learned

Some 2,075 of 7,120 respondents to our survey – almost 30 percent – made an interim stop at a second country before applying to immigrate to Canada. These respondents can be divided into three groups:

- Forty-three percent had second-country educational experiences only (n=902).

- In terms of raw numbers, Indian survey respondents comprised the largest number of applicants with second country educational experiences and no work experience. (n=226).

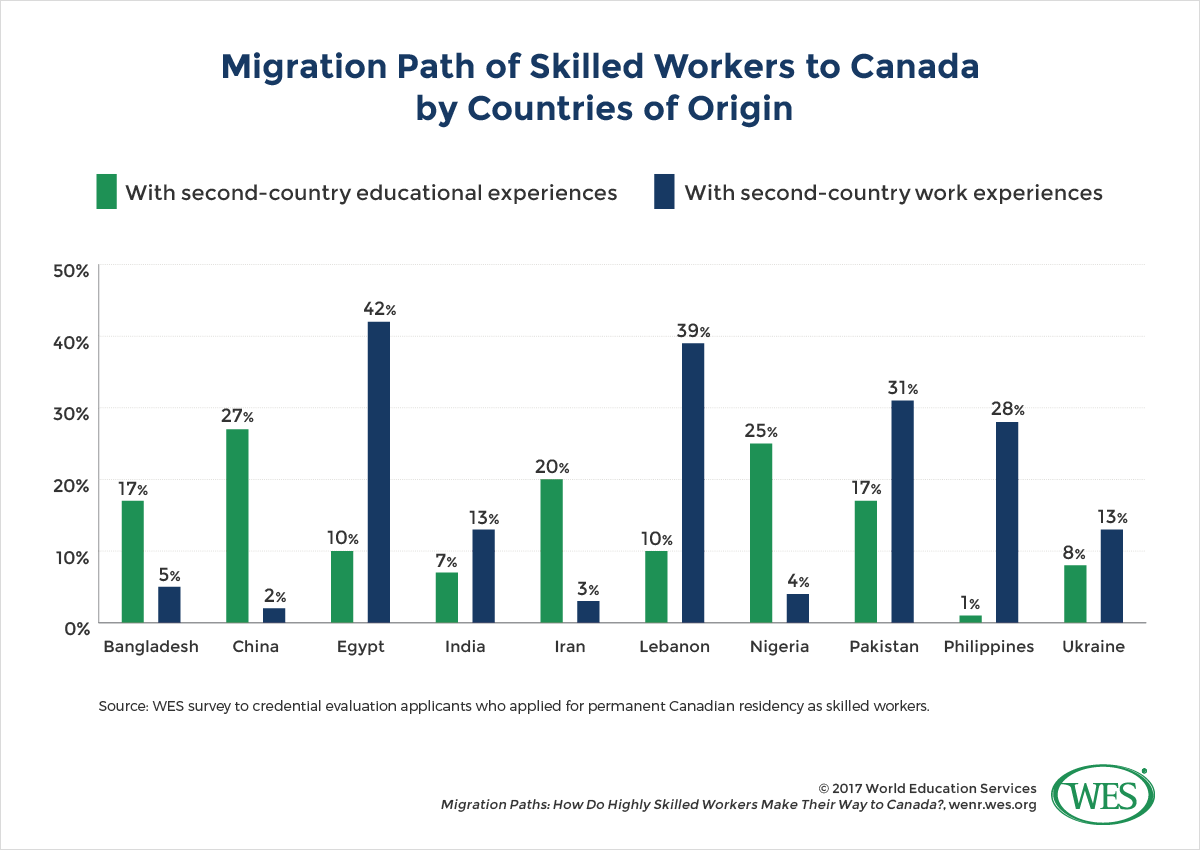

- China, Nigeria, Iran, Bangladesh and Pakistan were the top countries of origin with the highest percentages of survey respondents who had second country educational experiences but no work experience.

- The top five countries where this group completed coursework were: The U.K., the U.S., India, Australia and France.

- The highest level of educational attainment held by the majority of these respondents is a Master’s degree – held by 66 percent of respondents. Eight percent hold a doctoral degree.[1]By contrast, 41 percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin hold Master’s degrees. Two percent hold doctoral degrees.

- The most common fields of study are business and engineering, at 30 percent and 28 percent, respectively. [2]By contrast, 19 percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin hold business degrees; 31 percent hold engineering degrees. Math and computer science comes in third, at 10 percent.

- Forty-five percent had second-country work experiences only (n=933).

- In terms of sheer volume, Indian survey respondents again top the list, comprising the largest number of applicants with work experience (but no educational experience) in a second country (n=418).

- Egypt, Lebanon, Pakistan, Philippines, India and Ukraine were the top countries of origin in terms of those with the highest percentages of survey respondents with work experience (but no educational experience) in second countries.

- The top five countries where members of this group worked prior to immigration were: the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Qatar and the U.S.

- The highest level of educational attainment held by the majority of these respondents is a bachelor’s degree – held by 64 percent of respondents. Two percent hold a doctoral degree.[3]By contrast, 52 percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin hold bachelor’s degrees. Two percent of both groups hold doctoral degrees.

- The most common fields of study were engineering and business, at 31 percent and 18 percent, respectively.[4]By contrast, 19 percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin held business degrees; 28 percent held engineering degrees. Health professions, and math and computer science come in third, tied at 13 percent each.

- Twelve percent of respondents studied and worked in one or more countries other than their countries of origin. In other words, they left their countries of origin to study in Country 1, and then worked in or earned a second degree in Country 2, before finally immigrating to their destination country: Canada (n=240).

- The highest level of educational attainment held by the majority of these respondents is a master’s degree – held by 56 percent of respondents. Thirty-five percent hold a bachelor’s degree; seven percent hold a doctoral degree. [5]By contrast, 41 percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin hold master’s degrees. Two percent hold doctoral degrees.[6]Fifty-two percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin held master’s degrees. Two percent of both groups hold doctoral degrees.

- The most common fields of study are business and engineering, at 35 percent and 25 percent, respectively.[7]By contrast, 19 percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin held business degrees; 28 percent hold engineering degrees. Accounting comes in third, at 14 percent.

NOTE: In general, the prevalence of Indian applicants who apply to WES for credential evaluations related to Canadian requirements for the highly skilled worker program – and who have one or more degrees from a second or even third country – reflects our survey findings with regard to relative volume. From 2014-2016, for instance, WES received applications from 11,296 Indians who had received one or more degrees in a country other than their country of origin prior to applying. This number far outstrips the number of highly mobile applicants we see from any other country. The U.S. or the U.K. are the top two stop-over points for all the highly educated, highly mobile applicants we see. In the two years we examined, Indian applicants’ top flow-through country was the U.K., where some 4,853 received degrees. The second leading education stop-over for Indian applicants was the U.S., which accounted for 3,505 students. The number three education stop-over was Australia, which graduated some 1,029 of our 2014-2016 Indian applicants with post-secondary, second-country degrees. (The vast majority of these applicants held undergraduate degrees.)

To give a sense of the size of the gap in volume between highly mobile Indian and other applicant groups: The number two country of origin for U.K. degree holders applying for Canadian immigration in the same period was Nigeria, with 1,768 applicants.

What Drives Students from a Second Country to a Third?

What push factors account for the different migration paths of these education-only versus work-only respondents? A few are likely at play. For instance:

- Second-country Canadian immigrants with “education only” backgrounds most often came from either the U.K. or the U.S. – the two countries that routinely top the list of destinations for international students [3] around the world.China recently surpassed U.K. as the 2nd largest destination [4] for globally mobile international students. Work-related immigration restrictions in both countries may also contribute to the outflow of graduates to alternate work destinations. Even prior to Theresa May’s premiership, U.K. policies discouraged [5] non-EU international students from remaining in the country to work. In the U.S., meanwhile, a cap on H1B work visas [6] has long limited work opportunities for international students who graduate from U.S. institutions hoping to join the workforce long-term, forcing many U.S. educated graduates to seek work in other countries. More recent uncertainty around the optional practical training [OPT] visa program [7] may also contribute to high outbound rates among international students educated in the U.S. – with Canada as a likely destination. Most notably, draft executive orders, leaked last January, suggest, in the words of recent article in Science Magazine [7], “ a … threat to foreign postdocs, whatever their country of origin. Entitled ‘Protecting American Jobs and Workers by Strengthening the Integrity of Foreign Worker Visa Programs,’ the order [appeared] to target the OPT program, a vital bridge for many foreign students as they finish their Ph.D.’s and land postdoc stints.”[5] [8] The article goes on to note that in 2014, more than two-thirds of foreign students completing Ph.D.’s in the United States applied for OPT status.

- Second-country immigrants with work experience most often come to Canada from the United Arab Emirates, Singapore and Saudi Arabia. UAE, in particular, is a top destination for both high and low-skilled workers from around the world [9], many from India and Pakistan. Restricted pathways to UAE citizenship [10] are likely one driver of this populations’ high rate of migration to Canada. The fact that many Indian and Pakistani immigrants seeking skilled worker visas come to Canada seeking “a better standard of living (e.g. safety, comfort)” may indicate that abusive labor [11] practices also play a role, although in general, such practices are an issue for unskilled workers.

Pull Factors: Canadian Immigration Policy

Given the uncertainty surrounding professional opportunities in the U.S., a substantial portion of graduates and skilled workers may look for employment in Canada. In contrast to the United States, Canada has long used a merit-based immigration system designed to attract highly skilled immigrants. As Pia M. Orrenius of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas and Madeline Zavodny of Agnes Scott College noted in a 2014 report, “Canada has… a more educated immigrant stream than the United States” due to differences in immigration policies. “Canada primarily admits immigrants based on employment-related qualifications, while the United States primarily admits immigrants based on family ties… Immigrants are 1.5 times as likely as natives to have at least a bachelor’s degree in Canada, but only 0.95 times as likely in the United States. In both countries, immigrants outpace natives in terms of having any graduate degree or a Ph.D., but immigrants outperform natives more in Canada than in the United States.”[9]”A Comparison of the U.S. and Canadian Immigration Systems,” Orrenius, P., Zavodny, M.NRC Global High-Skilled Immigration Workshop, 2014.

Current and emerging U.S. policies are likely to add to this pool of highly educated immigrants. Canadian corporate immigration attorney and CBC senior writer Reis Pagtakhan echoed a widely held Canadian point of view when he wrote [12] that “the U.S. is mired in confusing messages regarding the direction of U.S. immigration policy…. Some multinational companies have asked Canadian immigration officials to step in to allow foreign workers — who may face restrictions on entering the U.S. — into Canada. As well, there are accounts of researchers now looking to Canada to continue their research as fears grow regarding their ability to live and work in the U.S.”

The Takeaway

Increased uneasiness is already apparent among members of some highly skilled immigrant communities in the U.S. In late February, the Seattle Times [13] reported that “some tech workers and others with temporary visas — and even some naturalized U.S. citizens — [in Seattle] say they aren’t comfortable making the biggest purchase of their lives as federal policies on immigration and foreign investment harden”. For its part, Canada is ready to absorb the impact. In March, an article in Toronto’s Globe and Mail [14] noted that, “as the U.S. border tightens for both political and bureaucratic reasons, the [Canadian] federal government is launching a new stream of its temporary foreign worker program to entice highly skilled workers to come to Canada. The program’s new ‘Global Talent’ pilot stream was announced [March 9] … Both the government and Canadian technology companies are heralding it as an opportunity to accelerate innovation and make the country more globally competitive, in turn spurring economic development to create more jobs for Canadians.”

With the U.S. judiciary repeatedly stepping in to block newly established visa restrictions imposed by the Trump administration, the long-term prospects of international students and skilled foreign workers now in the U.S. remain uncertain. However, Canada’s proximity to the U.S., its focus on creating a welcoming policy environment and its avowed belief in the economic benefits of skilled immigration ensure that it will continue to be a prime destination for the best educated, and most highly skilled graduates and workers from around the world.

References

| ↑1 | By contrast, 41 percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin hold Master’s degrees. Two percent hold doctoral degrees. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | By contrast, 19 percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin hold business degrees; 31 percent hold engineering degrees. |

| ↑3 | By contrast, 52 percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin hold bachelor’s degrees. Two percent of both groups hold doctoral degrees. |

| ↑4 | By contrast, 19 percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin held business degrees; 28 percent held engineering degrees. |

| ↑5 | By contrast, 41 percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin hold master’s degrees. Two percent hold doctoral degrees. |

| ↑6 | Fifty-two percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin held master’s degrees. Two percent of both groups hold doctoral degrees. |

| ↑7 | By contrast, 19 percent of respondents applying to immigrate to Canada directly from their country of origin held business degrees; 28 percent hold engineering degrees. |

| China recently surpassed U.K. as the 2nd largest destination [4] for globally mobile international students. | |

| ↑9 | ”A Comparison of the U.S. and Canadian Immigration Systems,” Orrenius, P., Zavodny, M.NRC Global High-Skilled Immigration Workshop, 2014. |