Bryce Loo, Research Associate, WES

The world is currently experiencing the largest refugee crisis since the Second World War, with 65.3 million individuals [1] displaced as of the end of 2015. Uprooted by wars, political conflict, natural disasters and more, residents of myriad countries have fled their homes to make their way in new encampments, cities, or countries. Over the last few years, the conflict in Syria has produced the largest number of these displaced persons, although they by no means constitute a majority.

Responses to this outflow have differed dramatically by country. European countries, especially Germany, have absorbed many. In North America, Canada has been – and remains – relatively open to displaced persons, resettling over 40,000 Syrian refugees [2] alone between November 2015 and January 2017. In 2016, the United States had begun to significantly increase refugee admissions [3] with “the highest number of refugee admissions in a single quarter since at least 2001 [4]” occurring in the final quarter of the year. Since the Trump administration took office, the country has been far less welcoming [5].

Political climate aside, there remains an urgent need [6] for institutions throughout North America to understand the needs of refugee students, both with regards to admission and on campus supports. The problem is where to glean this information: There’s been surprisingly little discussion of the details of efforts to date, in part, perhaps, because there’s little solid research on the topic, particularly out of Canada or the U.S.

To help fill that gap, this article seeks to provide insight into the scant research that is available, and summarizes preliminary data from an ongoing WES pilot project [8] designed to test a credential assessment process for refugees (and people in refugee-like situations) who do not have access to official documents.1 [9] This Canada-based pilot is relatively small in scale and includes only for Syrians at the moment, mostly in the Greater Toronto Area. Although still in an early phase, we believe that the insights gleaned are nonetheless valuable for institutions seeking to help refugee college applicants and students overcome some key hurdles.2 [10] Specifically, the article focuses on what higher education institutions seeking to enroll refugees need to be aware of in terms of:

- Legal status

- Factors related to acculturation

- Financial needs

- Family obligations

Missing Credentials: A Barrier That Can Be Overcome

Lack of important documents from their home countries, particularly credentials [11] such as diplomas or transcripts, can be a significant barrier for refugees and asylees who want to further their educations or careers. However, it’s a hurdle that institutions, licensing boards, and employers can help applicants to overcome. WES has done extensive research [12] on good international practices in recognizing the qualifications of refugees who lack full, official documents. We have developed a six-step model that individual institutions in North America and elsewhere can adapt to their own contexts and practices, whether credentials are assessed in-house or using outside credential evaluation organizations. Regardless of type of institution or program, or the level of applicant, lack of full credentials need not hold back bright, talented refugees from fully integrating into their host communities.

Who Is a “Refugee”? The Issue of Legal Status

The term “refugee” is sometimes loosely applied. However, the application of the legal status of refugees has important implications for individuals and institutions. Understanding a student’s specific legal status is key to addressing his or her needs, since this status determines what services and rights he can access. legal definitions have some slight differences, depending on context:

- International law defines the term “refugee” through the 1951 Refugee Convention [13] as a person “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”

- In North America, the term “refugee” (often called a “Convention refugee” in Canada) typically refers to resettled refugees, that is, individuals who have been chosen by the host government to be resettled [14] into the country generally from a third country.

Notably, potential applicants other than resettled refugees may also fall into the broad category of “displaced” persons. Asylum seekers [15] are generally covered under the international definition of “refugee.” Asylum seekers typically arrive in the host country under different circumstances than refugees who are official routed for resettlement; in many cases, for instance, they may arrive in a new country undocumented, and may only apply for asylum once there. In both the U.S. [16] and Canada [17], such persons may apply for asylum at a port-of-entry – an airport, seaport, or border crossing. (In Canada, these individuals are officially called “refugee claimants.”) After application, asylum seekers must wait – often a very long time – while authorities review and adjudicate their claims. This uncertain status can affect asylum seekers eligibility for certain types of aid, and may have implications for admission. Particularly in terms of financial aid, it is critical that institutional staff understand that refugee or asylee applicants’ legal status differs significantly from that of typical domestic students or international students.

The Politics of Refugee Status Designations

Jody McBrien is a Florida-based Ph.D. whose research focuses on refugee students and children affected by war. As McBrien notes, the definition of “refugee” is subject to exceptions based on political calculations. Understanding this nuance is particularly important when seeking to understand the status of undocumented immigrants. For instance, while some of these individuals are economic migrants – those searching for better job opportunities – many are also fleeing instability caused by natural disasters, war, or violence. One example includes migrants from several Central American countries, who flee to North America due to political instability or gang violence in their countries. These Central American migrants meet the international definition of a refugee; however, the U.S. government and other actors often label them as “illegal immigrants,” rather than refugees or even asylum seekers.3 [18] Thus, not only are they not entitled to any rights or services, but they are also subject to deportation.

Refugees and those who have applied for asylum are not legally the same as international students. Specifically: the temporary student visas that international students obtain in both countries typically impose restrictions of various kinds, including access to financial aid and employment opportunities, that do not pertain to refugees and asylees. In both the U.S. [19] and Canada [20], refugee students have access to federal student aid, as well as aid from most states, provinces, and territories. A student’s legal status can thus make a big difference when it comes to securing financial aid or receiving in-state or reduced tuition rather than paying higher out-of-state or foreign student tuition at public colleges and universities. In order to help refugee students, it’s therefore vital for institutions to understand these students’ legal status, and steer him or her to the appropriate resources.

Documentation concerns are thus critical as resettled refugees and asylum seekers seek to navigate the financial aid process. Doctoral research by Vivienne Felix highlights the importance of having documentation of students’ legal status, particularly when it comes to financial aid. In some cases, the students Felix interviewed needed a sponsor or agency to vouch for their status.8 [21] Without such sponsorship, access to in-state tuition or financial aid was, in many cases, problematic. (The financial challenges faced by refugees are addressed in greater detail below, in the section titled, “Money, Money, Money: Survival Jobs, Student Aid, Tuition Waivers & More.”)

For a review of processes and access to services for resettled refugees and asylum seekers (refugee claimants) in Canada and the U.S., see the table below.

Policies and processes for refugee resettlement and asylum in Canada and the United States

| Canada | United States | |

| Resettled Refugees | ||

| Types of refugee resettlement programs | Government-assisted [22]: All support comes from the Canadian Government or the Province of Québec

Privately-sponsored [23]: A unique model where refugees can be sponsored by a range of private groups, ranging from nonprofit and community organizations to groups of individual citizens Blended Visa Office-Referred Program [24]: A combination of support from the federal government and private sponsors |

U.S. Refugee Admissions Program [25]: Managed by the U.S. State Department, USCIS (United States Customs & Immigration Service) grants admission, and resettlement services are provided by the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) (Department of Health & Human Services) and nine nonprofit organizations in the U.S. |

| Referral for resettlement | Must be referred [26] by UNHCR or a private sponsor. | Referrals [25] usually are from UNHCR and occasionally from a U.S. embassy or specific nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). |

| Support provided after resettlement | Twelve months of income support [27] from either the government or a private sponsor, with a possible extension to 36 months of income support. Other integration support services provided. | Receipt of complete assistance [28] for up to 90 days through a resettlement agency (funding from ORR). After this time, refugees may apply to a variety of cash assistance programs [29] managed by the states. Other integration support services, including medical service, provided |

| Access to education | Immediate access at all levels, including federal and most provincial/territorial student aid [30]. Higher education students have varying access to reduced tuition by province/territory and institution. | Immediate access at all levels, including federal and most state student aid [31]. Access to in-state/reduced tuition varies by state and institution. |

| Access to work | Immediate. Refugees are expected to become economically self-sufficient as soon as possible. | Immediate. Refugees are expected to become economically self-sufficient as soon as possible. |

| Permanent residency | Usually granted immediately upon arrival [32] in Canada. | Required to apply for permanent residency [33] (a “green card”) after one year in the U.S. |

| Applying for citizenship | Must have been physically present in Canada [34] for at least four years out of the six years prior to applying. | Can apply after 5 years [33] residing in the U.S. |

| Asylum-Seekers | ||

| Access to education while awaiting a decision on status | Can apply for authorization [35] to attend a college or university. Generally not allowed access to federal student aid [30] until granted convention refugee status; access to provincial/ territorial aid varies. Minor children should have immediate access to K-12 education. | Should be able to access higher education but varies by state and institution [36]. Generally not allowed access to federal or state student aid [37] until granted asylum status. Minor children should have immediate access to K-12 education. |

| Access to work while awaiting a decision on status | Can apply for work authorization [35] only if able to demonstrate that the applicant cannot survive financially without working. | Ineligible to work [16] until either the claim is approved or 150 days have passed. |

| Information for denied applicants | See IRCC website [38]. | See USCIS website [39]. |

| Permanent residency | May apply [40] immediately after granted “protected status” (refugee claim approved). | May apply [41] one year after granted asylum status. |

Factors Related to Acculturation

One of the most basic issues for higher education institutions to consider is how long a refugee or asylum seeker has been in the host country. Researcher Vivienne Felix found that those who had arrived as younger children experienced more ease accessing higher education in the U.S. This was due to several factors: These students developed some familiarity with the U.S. education system while enrolled in earlier levels of the system; they also felt more comfortable with the English language, and U.S. culture.4 [42]

This gradual process of acculturation is typically of arrivals to new countries, whether immigrants or refugees. From the perspective of institutions seeking to admit or support this population, the upshot is that the process of navigating U.S. or Canadian higher education is more confusing for applicants who have arrived recently, and who were closer to college-age upon entry. These new arrivals need more support and guidance.

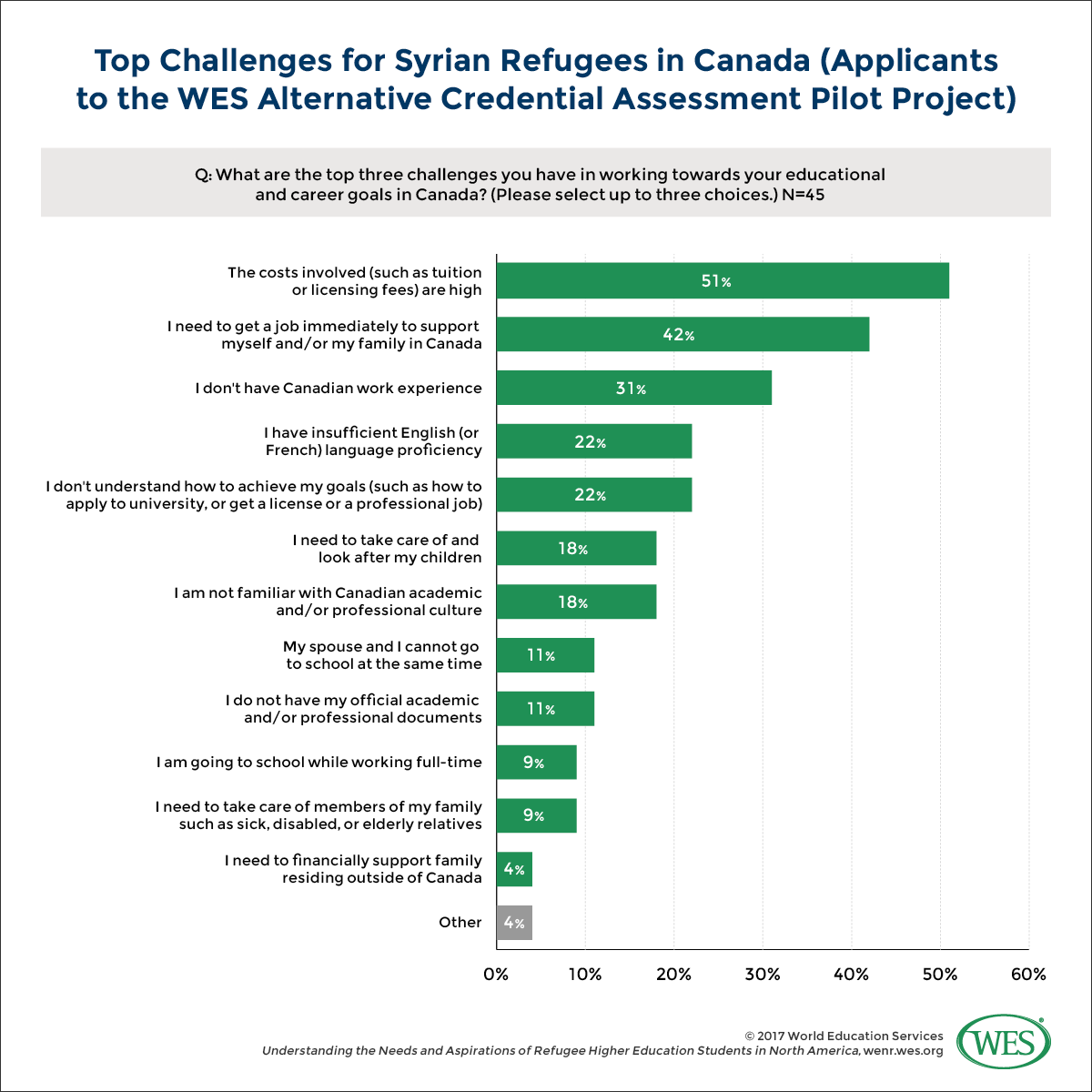

A WES survey of Syrian refugees applying for credential evaluation as part of our Canada pilot project, for instance, revealed challenges around the lack of understanding of the system and institutions in their new country. As one respondent wrote, “[For] any newcomer [who] has no Canadian experience of education… where should he/she go first? [T]o the labor market to get the Canadian experience first, or to the school to get a Canadian certificate? This is the key challenge.” Nearly one-quarter of all respondents to our survey cited “I don’t understand how to achieve my goals” as one of their top three challenges in striving towards educational and career goals, the fourth most cited of all barriers.

A recurrent theme during interviews with applicants of the WES pilot project was this lack of understanding of the Canadian education system. When discussing their assessment reports, some of these individuals mentioned that they didn’t understand major components that appear on a Canadian transcript, including semester credits or a GPA (grade point average). The grading system in Canada, which is roughly the same as the U.S. system, was also mystery. Even the term “grades” might be unclear, as “marks” is the more frequent English equivalent term used in Syria. More importantly, the context surrounding these terms was lost for many. For example, what does a certain GPA mean in terms of accessing further education in Canada?

In some ways, displaced students are like their peers among international student and voluntary immigrant communities: They have to learn new ways of doing things in the host country. However, lack of agency – and preparation – represents a fundamental difference. In one 2006 paper on refugee access to higher education, a Vietnamese refugee is quoted as saying:

It’s different and more difficult being an immigrant student in general—you have to learn a new language, culture, and academics— but being refugee means facing issues even beyond that. You escaped the country without preparation. You had no time to plan. And you didn’t plan to work. Most of us came very unprepared to face the educational system, and had to learn English, culture, everything all at once. It’s hard to get caught up. You have to be competitive to succeed and you have to do doubly, if not many times more work, just to stay even.5 [43]

Understanding this dislocation should be the starting point for setting up appropriate supports for this unique population.

“Information Worlds”

Even more mystifying for many refugee students in Canada and the U.S. may simply be the processes and institutional cultures surrounding higher education. Several applicants, most of whom (72 percent) already hold at least a bachelor’s degree, mentioned that in Syria, everything is done in person. In Syria, a student would meet with an institutional representative to complete all important tasks, such as applying to study. The staff member would ensure that all documents are in place, and all processes followed. The impersonality of the American and Canadian systems, where applications and other tasks are often completed online with little or no in-person contact with an institutional representative, is difficult for students from some countries to navigate.

Institutions trying to help refugees should keep these factors in mind. As researchers Saguna Shankar and colleagues at the University of British Columbia point out in a 2016 paper, “The role of information in the settlement experiences of refugee students,” “the settlement process could be improved through a better understanding of refugee students’ information worlds, the sources of information available to them, and the ways in which information needs and strategies may be incongruent with what information is available, and when and how it is delivered.”6 [44] Shankar and her co-authors further note that an ongoing relationship with an individual (or individuals) in admissions or student support offices is important for newly arrived refugee students, who may otherwise find institutions hard to approach or navigate.

Institutions can take a few steps to help students facing challenges with impersonal admissions or support processes.

- One is to assign a specific advisor in the admissions office, or perhaps in another office, to known refugee or asylee students. Being able to build a relationship and return to one individual with questions may be instrumental in helping refugee students gain enough understanding to make it through the admissions process.

- Developing workshops or seminars as well as booklets that help explain to students the basics of the U.S. or Canadian higher education system and the basic steps they should take to apply may also help.

- Institutions more strapped for time or with fewer human resources may want to look for community or even national partners (such as EducationUSA [45], for U.S. institutions) to whom they can refer students needing extra help through the process.

Strong, consistent communication is particularly vital. As Megan E. Mozina & Gerald P. Doyle of the Illinois Institute of Technology write in regards to helping Syrian applicants:

Overall, clear communication with applicants and colleagues is one of the most important elements to keep in mind, especially considering the inconsistencies and lack of trust that students face in conflict situations. Clear communication around eligibility, the application process, the importance of deadlines, costs (including fees, penalties, anticipated increases in tuition), and other such topics shows respect for them as individuals and for your process. Even simple acknowledgement of their emails and telling them by when they will hear from you again (and making sure you really do follow up by then) helps to reduce their stress and minimize the chances of them leaving their homes in conflict areas to check for an email that has not yet been sent. In our experience, being upfront and honest with Syrian applicants, in addition to being kind and empathetic, is a greatly appreciated relief in relation to the mirage of the past life from which many wish to escape.7 [46]

Money, Money, Money: Survival Jobs, Student Aid, Tuition Waivers & More

The sheer cost of higher education in Canada or the U.S. can be overwhelming for refugees or asylees. Over half of all respondents (51 percent) to our survey cited cost as one of their biggest challenges moving forward in Canada. The barrier was highest among traditional tertiary-aged students – 15 to 29 year olds, more than two-thirds (71 percent) of whom cited cost as a challenge. However, cost of tuition and fees was the top challenge among all age groups.

In order to survive financially (and, in some cases, provide for a family) and attend school, many students may either need to work full-time. From a policy perspective, both Canada and the U.S. contribute to this emphasis on work over education, since both emphasize financial self-sufficiency as a goal for refugees and asylees. The federal governments in both Canada and the U.S. (or the private sponsor in some Canadian cases) generally only support the refugee family financially for one year, though in some circumstances refugees can apply for ongoing aid. As a result, many new arrivals must get a “survival job” as soon as possible after arrival, regardless of whether or not the job matches their skill set. This catch-22 can derail many refugees who want to advance their education, or attend classes or training to put themselves on track to return to their original careers.

Observations from our Canada pilot bear this out: While 78 percent of our sample wished to pursue further education in Canada, 39 percent of them were working in a full-time job. Another 15 percent were working part-time or seasonally. One respondent to our survey explained the situation well:

Today I am doing a full-time survival job. I am not happy with this job because it cannot add any value to my career and it cannot lead to any improvement in my life over time. If I keep doing this job, the professional work experience that I brought with me to Canada will become worthless.

I have the motivation to do anything that could help me finding a job in my profession (examples: continue my education in any Canadian college/university; do one of the programs offered by the Employment agencies, etc.) but it is almost impossible to do any kind of [these] things in parallel with my full time job. If I quit my current job, there will be no resource[s] to cover my life expenses. The type of help I am looking for is a temporary financial support that could allow me to quit from my current job and do one of the programs that may help me finding a job in my profession.

Many refugees may seek significant financial aid, likely in the form of loans. Scholarships and tuition waivers directly from the institution can also provide refugee students with needed assistance. One of the best examples of institution-based funding to help refugee students is the model put forward by the Student Refugee Program (SRP) at the World University Service of Canada (WUSC) [47]. While WUSC-SRP handles the selection and placement of refugees into participating Canadian universities, the universities themselves fund each sponsored student through a variety of means [48], as well as provide integration support. Some institutions choose to allocate part of their budget towards scholarships or tuition waivers, while others use traditional fundraising methods to gain the funds necessary.

Another method is to use nominal student levies, often in which students on campus vote or consent to having a small fee added to their tuition each term to raise the money to fund one or a few refugee students on campus. For example, the University of Saskatchewan [49] adds $3.50 to every student’s tuition each semester to sponsor three or four students per year.

U.S. institutions could use similar means to help fund one or a few refugee students. The Institute of International Education’s (IIE) Syria Consortium for Higher Education in Crisis [50] has worked to coordinate such efforts among U.S. institutions, particularly for Syrian refugees. A Syrian student, Sana, at Bard College in New York was nearly fully funded through a combination of a full tuition scholarship and grants and donor funding from the local community, which provided for her housing and other expenses.9 [51]

Caretaker, Translator, and More: Balancing Family Responsibilities

Many refugee students in Canada and the U.S have significant family responsibilities. Some students, particularly older students, have their own families – a spouse and children – who may need support. For example, 42 percent of our survey respondents said that they needed a job immediately to support their families. However, even younger students without their own families may have familial financial responsibilities. Those who arrived with parents, siblings, or members of the extended family may know English better than their parents and other, particularly older relatives, and often become responsible for immediate family needs, such as taking members of the family to doctor’s appointments and translating.

These needs often take priority over education and other aspirations.10 [52] Students facing such obligations may need to know about flexible scheduling options, financial supports, and other contingencies such as the minimal number of credit hours and GPA required in order to retain financial supports, funding, and student status.

Language

Without the requisite language skills, refugee students will not succeed on campus in either Canadian or U.S. institutions. Many refugees lack proficiency in English (or French). Nearly 25 percent of our survey respondents, for instance, noted that their English or French language skills were insufficient to functioning appropriately in a higher education setting.

Some asylee and refugee students may need time in intensive language programs before applying to a regular academic program. Many universities and colleges have developed programs to help international students improve their English. Some have also developed programming for refugees or have integrated such students existing English language programs. Others have developed volunteer-run, low-cost programs that focus on language skills. A program at the University of Toronto [53], for instance, pairs domestic students who are seeking to learn Arabic with Syrian refugees who are trying to improve their English. The program not only allows everyone to improve their second-language skills, but has also helped Syrian refugees to establish critical social networks and better integrated through the friendships that have resulted.

Interestingly, English proficiency alone may not be adequate for success at American institutions. Research by Vivienne Felix, cited above, found that even those coming to the U.S. from countries where English is spoken still struggled with American English.11 [54] They had to adjust to American vernacular and accents, which made conversation and use of English in the classroom more challenging. (Those who resettled as children adjusted more easily.) Thus, even proficient English speakers will likely need some time to adjust to the local variety of English that is spoken.

Education as a Path Forward

Perhaps the most important thing for university and college staff to keep in mind is that education is vitally important to a large number of refugees who come to North America. Throughout the research on refugees accessing higher education in North America, a common theme has emerged: One of the greatest benefits of coming to Canada or the United States for refugees is the opportunity to access a high-quality higher education. Seventy-eight percent of respondents to our survey planned on enrolling in a higher education institution in Canada. One interview subject in Felix’s study, Laila, provided perhaps the clearest snapshot when she told her interviewer that her mother “always let me know… ‘YOU…you are going to college. That’s why we’re here… you’re going to college.’”12 [55]

Keeping this drive in mind may be all the impetus administrators need to help this population overcome multiple barriers to enrolling, graduating, and successfully integrating into their new communities.

1. [57] For further description of the WES Alternative Credential Assessment pilot project, see http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/syrian-refugees-documents-jobs-1.3770759 [58].

2. [59] An evaluation survey of applicants to the pilot project included an optional research survey component (n = 46), asking applicants about their goals and needs. We have leveraged these to make evidence-based recommendations, but it should be clear that extrapolation to large populations is somewhat problematic, and that findings may be adjusted as more evidence comes in. To date, the available research on refugee student experiences is, in most cases, similarly small in scale.

3. [60] McBrien, J. L. (2005). Educational needs and barriers for refugee students in the United States: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 329-364. Retrieved from http://www.refugeeyouthempowerment.org.au/downloads/3.1.pdf [61].

4. [62]Felix, V. R. (2016). The experiences of refugee students in United States postsecondary education. Doctoral dissertation, Bowling Green State University. Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file?accession=bgsu1460127419&disposition=inline [63].

5. [64] Quoted in Tobenkin, D. (2006). Escape to the ivory tower. International Educator, 15(5), 42. Retrieved from http://www.nafsa.org/_/File/_/escape_ivory_tower.ie_2006.pdf [65]. p. 46.

6. [66] Page 1, emphasis original. Shankar, S., O’Brien, H. L., How, E., Lu, Y. W., Mabi, M., & Rose, C. (2016). The role of information in the settlement experiences of refugee students. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 53(1), 1-6. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pra2.2016.14505301141/full [67].

7. [68] Page 37. Mozina, M. E. & Doyle, G. P. (2016). Defining the challenges and developing solutions: Illinois Tech’s support for Syrian students. In Supporting displaced and refugee students in higher education: principles and best practices. New York: Institute of International Education (IIE). Retrieved from https://www.iiepeer.org/node/2729 [69].

8. [70] Felix, 2016.

9. [71] Page 23 in Murray, J. (2016). Bard College: responding to Syrian refugee crisis in New York and Berlin. In Supporting displaced and refugee students in higher education: principles and best practices. New York: Institute of International Education (IIE). Retrieved from https://www.iiepeer.org/node/2729 [69].

10. [72] Shakya, Y. B., Guruge, S., Hynie, M., Akbari, A., Malik, M., Htoo, S., … & Alley, S. (2012). Aspirations for higher education among newcomer refugee youth in Toronto: expectations, challenges, and strategies. Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees, 27(2). Retrieved from http://refuge.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/refuge [73].

11. [74] Felix, 2016.

12. [75] Quoted in Felix, p. 122