Bryce Loo, Research Associate, and Jessica Magaziner, Knowledge Analyst, WES

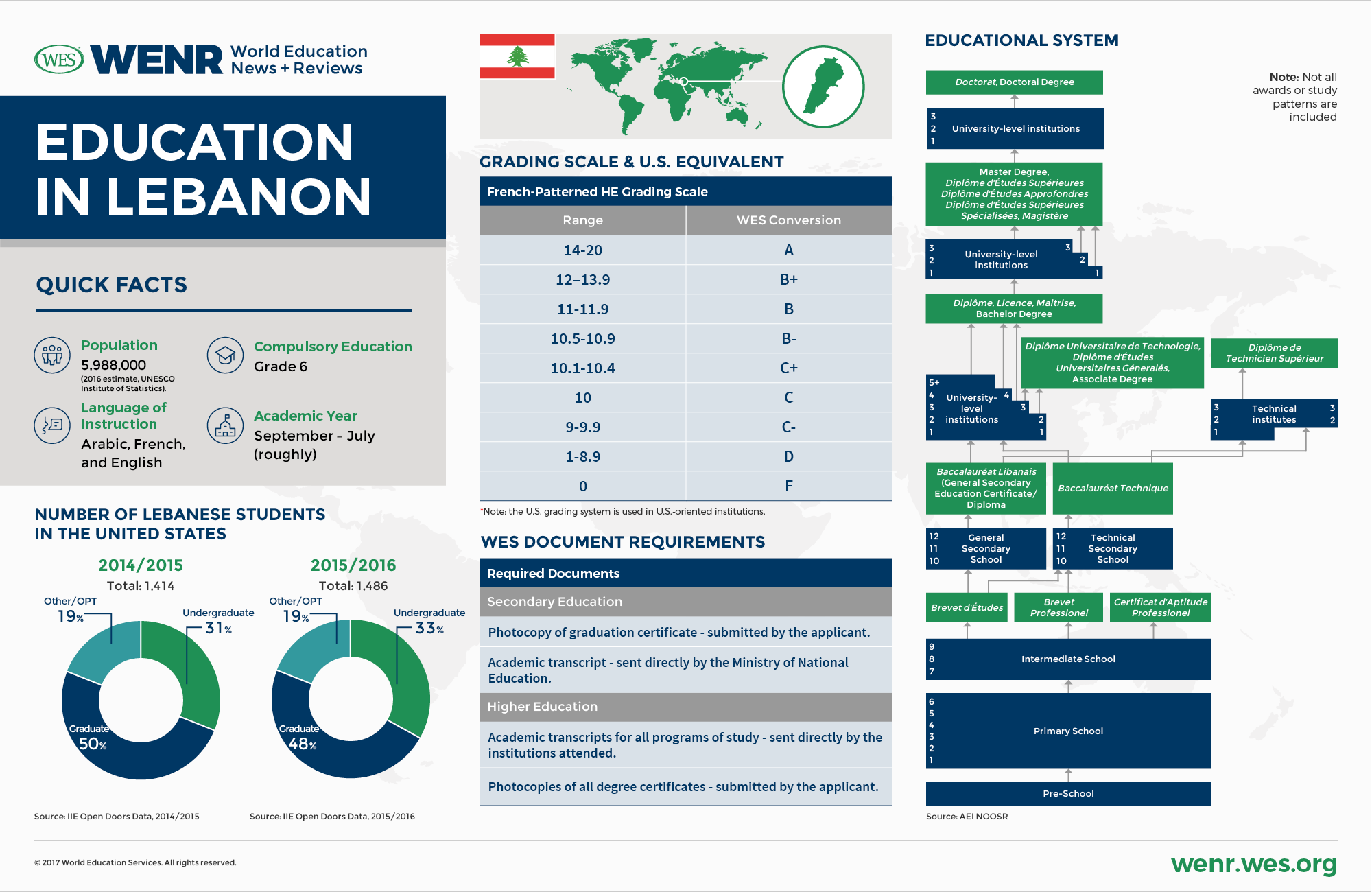

This article describes current trends in education and international student mobility in Lebanon. It includes an overview of the education system, and a guide to educational institutions and qualifications.

[2]

[2]

Once part of the Ottoman Empire’s province of Syria, Lebanon won its independence from France in 1943. Its modern borders were drawn by the French in 1920, under the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon [3]. During the French mandate, the National Covenant required that government leadership positions be divided up [4] by religious affiliation, and to this day, parliamentary seats are apportioned by religion.

Sectarianism [5] remains a major feature of modern Lebanese society, with religious affiliation – Christian (specifically Maronite Christian), Sunni Muslim, Shia Muslim, or Druze – being a primary marker of identity. Government institutions are often weaker than other actors, including religiously affiliated paramilitary forces. (The Shiite group Hezbollah is probably the most well-known of these organizations.)

Perhaps the most obvious examples of Lebanese sectarianism have been the series of civil wars fought in the country, the most recent of which ran from 1975 to 1990. Many of Lebanon’s neighbors, most notably Syria and Israel, have intervened in Lebanese politics, and been involved in conflicts with and within Lebanon. Lebanon has become a major country of asylum and resettlement for various refugee groups [6], including Palestinians, Iraqis, and, most recently, Syrians. As a small state with a history of conflict and sectarianism itself, Lebanon has struggled with and often resisted integrating refugee groups into society and particularly into its education system.

Lebanon continues to suffer under a weak government and economy, a situation that is further compounded by lack of social cohesion. An ongoing garbage crisis [7], which began in 2015, sheds light on the broader situation. For two years and counting, the government has been unable to provide basic garbage collection services to the country. Even more striking is that the country went for nearly two-and-a-half years without a president due to political gridlock among the various religiously-based sects, before finally choosing Michel Aoun [8], a Maronite Christian, to take over the post in October 2016. Other signs of instability are clear as well: In 2016, youth unemployment [9] was 21.27 percent, more than triple the overall unemployment rate [10] of just 6.78 percent.

The weakness of the government is reflected by problems in the public education sector. At the primary and secondary levels, Lebanon has struggled to increase the quality of public education [11] since the end of the civil war. The tremendous influx of Syrian refugees in recent years [12] has further strained the public education system, and has reportedly led some Lebanese parents to move their children from public to private school [11]. In 2015, a striking majority of Lebanon’s 491,455 elementary age students [13] – nearly 75 percent – attended private schools. At the same time, transition rates from elementary to secondary education have plunged in recent years, as have gross enrollment rates in higher education.

The country has high literacy rates – around 99 percent for both male and female youth – as of 2015, according to the World Bank [14]. Roughly 2.6 percent of GDP was spent on education in 2013, which is low compared with the eight percent average spent among OECD nations [15].

Outbound Tertiary-Level International Student Mobility

According to a 2012 European Commission [16] report on higher education in Lebanon, “Lebanese higher education is [characterized] by a historical openness to the outside world… It is hard to find one institution that does not have a convention or an agreement with one or more institutions in the region, in Europe, in Canada or in the United States. However, there are no national policies or measures to promote the foreign mobility of students during their higher education studies.”[1]“Higher Education in Lebanon,” European Commission for Higher Education, July 2012.

In 2015, 14,232 Lebanese students were seeking degrees abroad, according to UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS) [17].competition for seats [18] at Lebanon’s top institutions. Many students may also view education as a spring board to employment abroad; others may be seeking a path to immigration– both likely drivers in the face of high unemployment at home.

The top five destinations for outbound students are, in order, France, the United Arab Emirates, the United States, Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom. France’s position as the top destination is likely due to post-colonial and linguistic connections between the two countries. Finance, business, engineering, and law are among the most popular fields of study for Lebanese abroad, according to ICEF Monitor [18].

France’s two-decades of colonial rule have had a long-lasting impact [19] on the modern Lebanese education system. The degree structure in the higher education system, for instance, follows that of France’s system, and French is an official language of instruction. Post-independence Lebanon made efforts to focus more closely on offering instruction in Arabic, and teaching Lebanese culture and history. These factors may well account for the high degree of outbound student mobility from Lebanon to France.

In the 2015-16 academic year, the U.S. hosted some 1,486 Lebanese, according to the Institute of International Education’s Open Doors Report [20].Canada [21] hosted 872 Lebanese students in 2015.

Inbound Tertiary-Level International Student Mobility

According to UNESCO UIS [22], there were 17,495 international students studying in Lebanon in 2014 – a significant decrease from a total of 33,178 in 2011. While the reasons for this are not entirely clear, the general situation in Lebanon and the region – between internal political strife in Lebanon and civil war and fighting in neighboring Syria and Iraq – may be playing a significant role. There are not great data on where these incoming students are from, although Lebanon may have begun to receive more American and Western students due to turmoil in neighboring countries that traditionally hosted a lot of Western students, such as Egypt and Syria.

In 2015-16, only 37 U.S. students were documented studying abroad on short-term programs in Lebanon, according to IIE’s Open Doors Report [23]. (Similar data do not exist for Canadian students in Lebanon.) 2012 article in USA Today [24] mentioned that 700 U.S. citizens were studying at AUB.

The U.S. State Department [25]Canadian government [26] has issued a similar warning.2015 suicide bombing attacks in Beirut [27], may deter some from studying in Lebanon.

According to government requirements [28], international students can enroll in Lebanese universities and colleges by fulfilling the same entrance requirements as domestic students. In many cases, they need to demonstrate proficiency in Arabic, French, or English, depending on the institution and program. Some institutions provide language courses or training. They would then receive a visa to study in the country.

Administration of Education System

Elementary, secondary, and higher education in Lebanon are all overseen by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE) [29] (Ministère de l’Education et de l’Enseignement Supérieur). Within the ministry are the:

- Directorate General of Education

- Directorate General of Higher Education

- Directorate General of Technical and Vocational Education

Also under the auspices of the MEHE is the National Center for Educational Research and Development [30] (CERD; CRDP in Arabic). CERD provides technical expertise on the Lebanese education system to both local and international bodies. It is also develops and issues textbooks related to the national curriculum.

Lebanon has both public and private schools. Both teach the national curriculum.

Technical and vocational education (TVET) is run separately [31] from the rest of the education sector, under the direction of the Directorate General for Vocational and Technical Education (DGVTE). In 2012, the Lebanese government revised its approach to TVET fields, levels and certificates, issuing legislation and establishing a new framework focused on 4 areas:

- Reviewing and upgrading programs and specialties

- Reviewing and upgrading the academic structure of the TVET system

- Developing qualified human resources, and upgrading financial and physical resources

- Strengthening the sectors ties to local and private partners

Lebanon has low levels of education spending, both from a global and a local perspective. As noted in one 2014 report by BankMed [32], a Lebanon-based banking company, “the government spent in 2012 an amount equivalent to 1.6 percent of GDP on education. This amount compares to 3.8 percent of GDP spent on education in each of Kuwait and Egypt, 5.4 percent spent in Oman, and 6.2 percent spent in Tunisia.”

Elementary Education (Grades 1 to 6)

Formal education [28] in Lebanon begins at age 6 and is compulsory until age 11 or 12 (grade 6). Elementary education lasts for two “cycles” (as they are typically called in Lebanon), each three years long.

Arabic is the main language of instruction at the elementary school level, but English or French are taught beginning in early elementary school. The main subjects of study at the elementary level include Arabic, civics, art, mathematics, science, and physical education. Religion is not a mandatory subject [33] but is sometimes included. By law, math, physics, and chemistry are taught in either English or French.

Per UNESCO UIS [34], the progression rate from elementary to intermediate education dropped slightly from 99.1 percent in 2013 to 89.3 percent in 2014 – considerably lower than it has been any time since at least 1998.

Intermediate Education (Grades 7 to 9)

Intermediate (or lower secondary) education [33] lasts three years (one cycle), until roughly age 15. At the beginning of intermediate study, students enroll in one of two streams – either academic or technical/vocational.

Subjects included in the academic stream are Arabic, initial foreign language, second foreign language, civics, geography, history, art, mathematics, science, technology, and physical education. Students must sit for and pass the Brevet examinations, a series of nationwide exams on a number of subjects studied only in the third year of intermediate school, as well as subjects studied for all three years. (There have been calls [35] recently by some in the Lebanese government to abolish these exams.) Upon passing, they earn the General Education Diploma, or Brevet d’Etudes.

Formal Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET [31]) begins at the intermediate level. Both at the intermediate and the more advanced secondary level, TVET is broken down into technical education and vocational education. The former is more theory, math, and science-oriented , while the latter is more applied and practical in nature.

At the intermediate level, vocational students can, upon completion of two or three years of study, earn the Certificat d’Aptitude Professionnel (CAP) in one of six specializations.

Technical students earn the Brevet Professionnel (BP) after two years of study beyond the first general education year of intermediate education, and after either passing the requisite examination, or obtaining a Certificat d’Aptitude Professionnel. The BP has 15 specializations including hospitality, basic accounting, and cosmetology.

Secondary Education

Students must hold the Brevet d’Etudes to continue on to general secondary school or the Brevet Professionnel to continue on in TVET at the secondary school level [33]. According to World Bank [36] statistics, the lower secondary completion rate for both sexes fell from almost 66 percent in 2007, to 59 percent in 2013.

Secondary (or senior secondary) education [28] lasts three years, generally from ages 15 to 18. Students at this level attend either a general education secondary school or a technical secondary education school based, in most cases, on their Brevet d’Etudes examination results. The general education track includes humanities, economics, life sciences, and sciences. (The technical track is discussed in more detail below.)

In 2015, the overall gross graduation rate [37] in Lebanon was about 58 percent – down substantially from the 2010 gross graduation rate of 82 percent, and roughly average for the broader Middle Eastern region.[7]Rough averages are all that is available, as data for the greater Middle East region can be in short supply.

General Secondary Education Track

In the Lebanese curriculum, the first year of secondary school is a “common” year [33], where everyone takes the same courses. The majority of coursework during this year is in languages (Arabic and foreign languages), mathematics, and sciences. The subjects studied in the second and third years are largely the same for all students, but the amount of time spent on each subject varies by stream.

The four main groups of subjects that secondary students take are languages (Arabic and foreign), civics (e.g., history, geography), mathematics and sciences, and miscellaneous subjects, such as computer science, art, and physical education. Philosophy is introduced as a mandatory subject in the second year.

In the final year, students take the Lebanese Baccalaureate Exams in the fields studied. Students are then awarded the Baccalauréat (or, in Arabic, Shahaadat Al-Bakaalouriya al Lubnaaniya l’il-ta ‘liim al- Thaanawi – Al-Thanawiyah Al-Aamah Al-lubnaniah), sometimes also known as the Baccalauréat Libanais. This degree is often now called, in English, the General Secondary Education Certificate, or General Secondary Diploma.

Some private schools [19] offer the International Baccalaureate [38] (IB), American, French [39], or another international curriculum instead of the Lebanese. Students at private secondary schools in Lebanon will typically sit for that particular external examination (e.g., French Baccalaureat exam, the IB exam) and receive that particular system’s qualification.

Secondary-level Technical and Vocational Track

After obtaining a Brevet Professionnel certificate, students may continue into technical or vocational secondary education. Technical students [33] earn the Baccalauréat Technique (Al-Bakaalouriya al-Fanniya) after passing an examination or the Certificat Professionnel de Maîtrise.

The Baccalauréat Technique requires some general education – including Arabic, foreign languages, mathematics, science, and civics – and selection of a concentration within one of three streams: agriculture, industry, or service.

The Certificat Professionnel de Maîtrise is a vocational certificate that does not require general education, but does require practical training in the workplace. Students of this certificate may sit for the examinations for the Baccalauréat Technique, which allows for access to general higher education [40] as well as post-secondary technical and vocational education.

Secondary Qualifications

Lebanon’s secondary exit qualifications have evolved considerably over time. Until 1990, Lebanese secondary study was separated into two examinations. The Baccalauréat – Première Partie (first part) examination was taken at the end of the second year of upper-secondary study and the Baccalauréat – Deuxième Partie (second part) examination was awarded at the end of the third year. From 1991-2000, the Baccalauréat Libanais examination was offered at the end of the third year of secondary study before the name was changed in 2001 to the General Secondary Diploma (also called the General Certificate of Secondary Education).

Civil strife in Lebanon has repeatedly led to cancellation of the Baccalauréat, especially during the civil war of 1975 to 1990. In 2014, the Baccalauréat was administered, but not graded due to a teacher’s strike. The Ministry of National Education has issued an affidavit stipulating that due to the unique circumstances of the 2014 examination period, the ungraded final examination certificate should stand as proof of the student’s eligibility to enter higher education. In such instances, WES usually considers the credential equivalent to a high school diploma in the United States and a secondary school diploma in Canada.

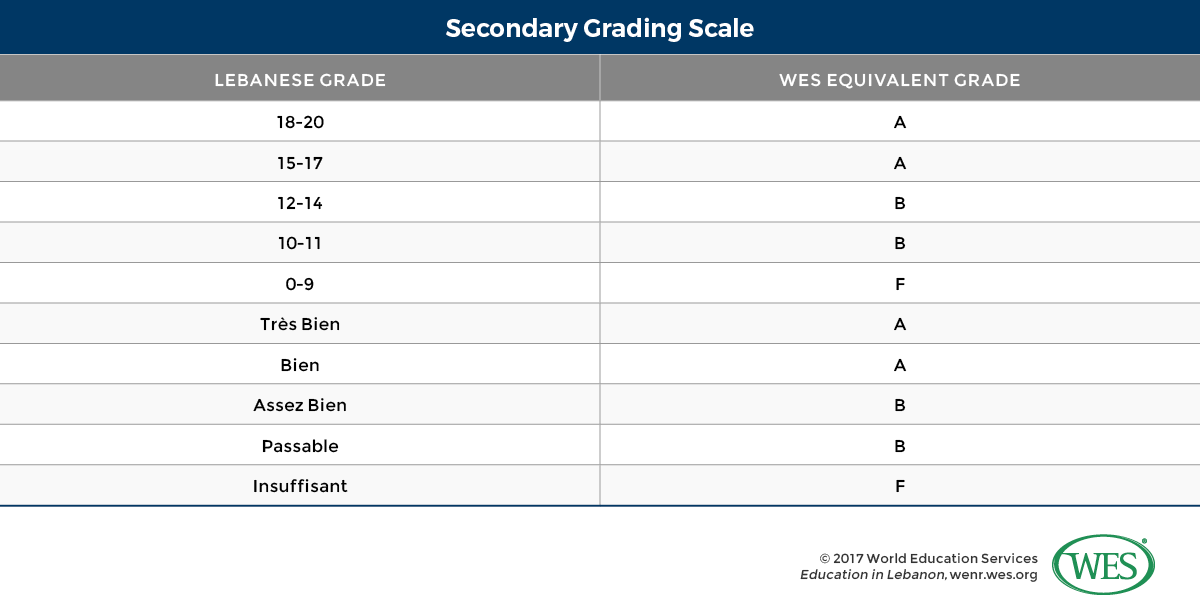

Secondary Grading Scales

Grading in the secondary school system generally utilizes the French system of 0 to 20 points, with the following descriptions used:

- 18-20: Excellent (Excellent)

- 15-17: Very good (Très bien)

- 12-14: Good (Bien)

- 10-11: Pass (Passable)

- 0-9: Fail (Insuffisant)

WES equates Lebanese grades with the following American/Canadian grades in the following manner:

Some schools use the American grading system with percentages and letter grades.

Higher Education: A Complex Model

Lebanon’s education system is notable for the dual countries that helped to shape it. This has resulted in a distinct system divided between French and American-patterned higher education institutions. Some institutions have implemented combined models, some of which may incorporate Egyptian-Arab or more localized dimensions. A few have adopted other international systems, most notably the Canadian or German university model.

Evaluation of documents can thus be tricky. Variations in language and terminology are common, which is difficult from a credential evaluation perspective. The language of instruction [42] in Lebanon can depend on the institution attended, but programs of study are typically offered in Arabic, English, or French, and the language of instruction can lead to differences in the language found on academic documents. A French-patterned institution, such as the Université Libanaise (the Lebanese University) may offer documents in French or English. In some instances, academic transcripts may be issued in English and refer to a bachelor’s degree program, while the degree certificate may be issued in French and indicate that the degree conferred was a diplôme de licence.

On the other hand, a French-style institution could also offer a three year university degree and refer to it by an American degree name (e.g., Bachelor of Arts). Similar to American and Bologna-reformed European systems of higher education, Lebanese higher education utilizes three progressive cycles [19]: bachelors level, masters level, and doctoral level (or, in the French model, licence, master, and doctorat (LMD)). began implementing this three cycle structure [16] in their faculties in 2005, though implementation has not been immediate or uniform.

To rationalize these multiple systems, MEHE maintains an Equivalence Committee [43], set up in 1962. The committee acts as “the only [official] reference for … recognition of certificates and the equivalency for education levels in various domains (general education, higher education, and technical and vocational education.)” The committee also provides general curriculum guidelines [16] to universities, which use the guidelines to develop their curricula, before submitting them back to the committee for approval.

Quality and Governance

As of early 2017, the state of quality assurance and accreditation in the Lebanese higher education system is apparently in limbo. The Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE), and a group of Lebanese universities partnered with the European Union starting in 2011 to develop a quality assurance framework and agency for Lebanese higher education. The project is known as TLQAA (Toward the Lebanese Quality Assurance Agency) [44]. According to a 2015 paper by the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut, the project resulted in a draft law “to establish a national agency for quality assurance in higher education that would hold (private and public) institutions accountable for [services provided] to the public.”

However, the draft law, like so much else in Lebanon in recent years, fell prey to “the inactivity of the parliament” as well as political factors and “personal interests” among owners of private universities.[9]El-Ghali, Hana Addam and Ghalayini, Nadine, “Leveraging the Quality of Higher Education in Lebanon: Study Summary Report.” Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs, American University of Beirut, July 2015 Special interests have, according to researchers at the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs, been particularly prominent in slowing passage of effective accreditation reforms. “The Lebanese University and some of the private institutions of higher education used their political connections to attempt to modify the draft both during the formulation of the law as well as during the review of the draft at the meetings of the various parliamentary committees. The power of the Lebanese University and the other groups stemmed from political resources. In many cases, the stakes were too high, particularly for some of the private institutions that were owned by some politicians or controlled by some political parties,” noted a 2016 policy brief entitled, “Why Doesn’t Lebanon Have a National Quality assurance Agency Yet?” [10]El-Ghali, H. and Ghalayini, N, “Why Doesn’t Lebanon Have a National Quality Assurance Agency Yet?” Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs, American University of Beirut, Policy Brief #4, March 2016.

There are currently 31 accredited private universities listed [45] by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education. Per the joint TLQAA report from the MEHE and the European Commission [46], the DGHE requires that new institutions meet a relatively slender handful of requirements in order to receive a license from the DGHE. These include (verbatim):

- Institution Regulations: These regulations should show that the main objective of the institution is higher education and that the institutions committees and bodies bylaws guarantee their independence from the legal entity requesting the license.

- Buildings and Infrastructure: The buildings should be independent and dedicated to the university or faculty. The surfaces and facilities should respect the needs of the academic program to be offered.

- Scientific Equipment: Laboratories facilities and libraries should be available and according to the need of the programs to be offered.

- Academic and Support Staff: A professor should be envisaged for each 20 students including one full-timer for each 30 students. 50% of the professors should hold a PhD or the highest degree in their specialization. 90% of the professors should be Lebanese. The support staff should have expertise in their domains.

- Start of Operations: No teaching or operation should start before satisfying the conditions of licensing and before a written authorization from the directorate general after verifying that the conditions are respected. [11]Higher Education in Lebanon,” European Commission for Higher Education, July 2012.

Beyond that, says the TLQAA:

The Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE) has introduced some quality assurance procedures in their traditional licensing mechanisms intended for establishing a higher education institution. The licensing mechanism is applied at the MEHE through the Council of Higher Education and the associated technical committees.

The process starts with the receipt of a file that ought to be [analyzed] by a special technical committee, which produces a report and carries out some follow-up of the dossier. Based on the report from the technical committee, the Council of Higher Education issues a recommendation for licensing. The final decision on licensing a higher education institution is left to the Council of Ministers. A start-up process, followed by an audit visit or an on-site visit to verify the institution’s compliance with the licensing criteria, leads to the recognition of the [programs] and the diplomas awarded to students.

While this sounds like a well-designed system, implementation remains problematic.

“No proper quality assurance and accreditation mechanisms are in place at national level,” the TLQAA reported in 2012. internal procedures [46] meant to address the issue. However, given the overarching political gridlock in Lebanon, inconsistent processes and controls are likely still the order of the day.

Accreditation in Practice

The MEHE division responsible for oversight of both public and private institutions of higher education [19] is the Directorate General of Higher Education (DGHE). However, many institutions are accredited by external bodies in the USA and Europe.accredited by [19] the Middle States Association of Schools, while the Lebanese American University is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. (Both also have Lebanese government recognition.) Some French-modeled universities have accreditation or official recognition from French organizations [46].

The only public institution of higher education in Lebanon, Université Libanaise [16] (the Lebanese University) is, according to Dutch non-profit Nuffic, “automatically accredited by the Lebanese state.”Established in 1952 [40], it also has a high degree of autonomy – as can be gleaned by the reported scope of its influence on draft accreditation regulations.

Nuffic also noted in a 2016 report that 39 percent of all Lebanese students [19] attend the Lebanese University.[15]”Education in Lebanon: The Lebanese education system described and compared with the Dutch system,” EP-Nuffic (2016). While enormous, that share represents a significant drop from decades past: As recently as 2000-01, the institution enrolled as many as 60 percent of all Lebanese higher education students. A sharp uptick in the number of private universities in Lebanon is likely the primary cause.

Funding for Higher Education

According to a 2012 report from the European Commission [16], government expenditures on higher education are less than 0.5 percent of the GDP.

The Lebanese University, which is almost totally free for students, is the main university recipient of direct government spending, along with governmental agencies overseeing education.

A large percentage of funding for the sector comes from individual students and their families, particularly as a majority of individuals attend private institutions. Private institutions generally raise most revenue through tuition and fees. Such tuition and fees range greatly. For 2016-17 academic year, for example, the American University of Beirut (AUB) charged [47] anywhere from US$552 to $816 per credit, depending on the program. Graduate students paid between US$756 and $1,002 per credit. The institution does not charge students beyond 15 credits. The French-modelled University of Saint Joseph has annual tuition and fees [48] at the undergraduate level ranging from roughly US$14,000 to over $50,000 depending on the program.

A third stream of revenue comes from external sources, including foreign governments (especially France), private organizations, endowments (for American-modeled universities), and religious groups, who often donate land, money, or labor for religious-based private institutions.

The Private Sector: Massification, Licensure, and Other Issues

In 1961, a new higher education law went into effect in Lebanon, opening the way for private institutions to flourish. There were only six such institutions in 1961, when the law first came online. These included the prestigious American University of Beirut (which recently had its 150th anniversary [49]), and the University of Saint Joseph, which was established by Christian missionaries. Even today these institutions maintain international credibility: The American University of Beirut (AUB) appears in the Times Higher Education (THE) World Ranking of Universities [50] for 2016-17. AUB is ranked second in the THE list of top universities in the Arab World [51]. AUB, Saint Joseph University (founded in 1875), and the Lebanese American University (founded in 1924) are ranked in the QS World University Ranking [52] from Quacquarelli Symonds (QS).

Growth in the private higher education sector was initially sluggish, until the end of a 15-year-long civil war in 1990. Al-Fanar Media [53] reported that, between 2004 and 2013, higher education enrollments increased from 120,000 to 210,000. In 2016, the AUB Policy Institute similarly noted that, “The number of institutions of higher education has tripled in the past decade, coupled with a sharp increase in the number of students.”

In addition to the flagship campuses of private institutions [40], most in Beirut or neighboring Mount Lebanon, a number of branch campuses, not all of which are licensed by the government, have also proliferated.

Higher Education: Admission and Degrees

Admission Requirements

The Baccalauréat Libanais or Technique is the only government-mandated requirement [40] for enrollment in tertiary education, and guarantees admission to the country’s only public university, Lebanese University. Other institutions may set additional language or other requirements over and above the Baccalauréat. Many institutions utilize math and science placement exams [40] for incoming students.

Some American-modeled universities admit students on the basis of a high school diploma, TOEFL scores, and SAT scores. (Either the SAT, or sometimes the SAT subject exams may be required). For instance, for the 2016-17 academic year, the American University of Beirut (AUB) required [54] SAT reasoning scores (reading and math) for admission into either freshman year (a “majorless year”) or sophomore year (first year of a student’s major).

Note also that many students receive advanced placement in university programs based on their Lebanese secondary examination results, and can be exempted from up to one year’s worth of credit from based on the Baccalauréat examinations. This can be difficult from a documentation perspective because many four-year bachelor’s degree programs may look like three-year programs based on the academic transcript.

Refugee Education in Lebanon

As a result of the numerous conflicts around it, Lebanon has become one of the world’s major hosts of refugees. The Syrian civil war, which begun in 2011, has caused massive movement of Syrians to Lebanon. As of the end of 2016, 1,011,366 Syrian refugees were registered by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [55] (UNHCR) in Lebanon, the second largest number of Syrian refugees after Turkey. Among those displaced are numerous higher education students and scholars. A large number of urban, middle-class Syrian refugees have fled to Lebanon. According to a joint study [5] conducted by the Institute of International Education (IIE) and the University of California (UC), Davis, as many 26 percent of urban Syrians of university age attended higher education until at least the start of the war. Around half were women.

Many Syrian students and scholars who fled to Lebanon have been unable to gain access to higher education [5] once there, and are now in protracted refugee situations that have lasted five years or more. Contributing factors include language, and differences between the Lebanese and Syrian education [56] systems. In particular, the fact that most universities use English or French as the main medium, rather than Arabic, is problematic for many otherwise qualified Syrians.

Cost is another challenge both to initial access and beyond, as many Syrians lack the funds and access to financial aid to afford university. (This is true even of the public Lebanese University.) Many Syrian students in Lebanon work long hours for relatively low pay, making access to higher education tough both in terms of time and money. (Employment of Syrian refugees is technically illegal, though it is reported that there is little enforcement of this law by government officials. Given this situation, exploitation of Syrian workers is an additional concern.)

Additional barriers include sectarianism, and the fact that Lebanese universities, which are most often in urban centers, are often geographically inaccessible to refugee communities. That said, some Lebanese institutions, including the American University of Beirut, Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth (Saint Joseph of Beyrouth University), and the Lebanese University, have admitted Syrians.

Post-secondary Technical and Vocational Education

Students pursuing post-secondary technical and vocational education (TVET) may enroll at technical colleges, which offer 27 different specializations. These programs typically require two to three years of study following the Baccalauréat. The resulting qualification is a Diplôme de Technicien Superieur (Diploma of Higher Technician) (Shahaadat ul-Imtiyaaz al-Fanni).

After one additional year of study and examination, students may earn a Licence Technique (LT) in one of ten specializations. Some technical-based qualifications require students to pass a national examination. This generally means that study is completed during the academic year at a technical institute and then students sit for an examination at the end of the program. In order to evaluate this study as a completed degree (e.g., Diplôme de Technicien Supérieur, Licence d’Enseignement Technique), WES requires the official examination results to be sent directly by the appropriate Ministry or examining body.

There are no standardized transfer policies or procedures [16] for students who wish to move from the academic track to TVET programs. However, a Baccalauréat Technique is the only way for a student to gain admission into university programs from the TVET track.

Non-formal and informal TVET training programs [31], including apprenticeships, are also common.

Undergraduate Education: Academic Track

Undergraduate educational programs vary depending on whether on institution follows the French or American model, or some hybrid thereof.

The American-patterned system is similar to undergraduate programs offered in the United States. It includes a U.S.-style credit system, and provides a focus on general education classes and electives. It typically takes four years of undergraduate study to obtain a bachelor’s degree in the American system. However, many Lebanese students are granted exemptions based on their Baccalauréat scores, and bypass the first year.

Instead of a standardized four-year bachelor’s degree, French-style institutions offer [33] three- or four-year Diplôme de Licence degrees typical of the French-patterned LMD (Licence-Master-Doctorat).Bologna Process [57]. French-patterned programs require fewer general education requirements that American-style programs, and use coefficients in place of credits.

Both the American and French systems offer several sub-degrees.

- In the American system, two years of an American-modeled undergraduate program can lead to an associate’s degree. Another two years of study beyond the associate’s degree usually can result in a bachelor’s degree.

- In the French system, students can take a more specialized track of study and receive a Diplôme Universitaire de Technologie (DUT) or Diplôme d’Études Universitaires Générales (DEUG) after two years of study (usually with no American-style general education component).

- The Diplôme Universitaire de Technologie is designed to be applied in nature, and includes a practical training component.

- The Diplôme d’Études Universitaires Générales is structured to be more academic and lead to further education.

- One year of additional study can usually result in the award of a Licence.

A three-year program is generally up to 99 credits [19], and a four-year program is up to 144 credits. For institutions that use the ECTS (European Credit Transfer System), a three-year bachelor’s degree is generally 180 ECTS credits.

A majority of institutions use [40] English or French as mediums of instructions, sometimes a combination of the two, with some exceptions such as for Arabic literature.

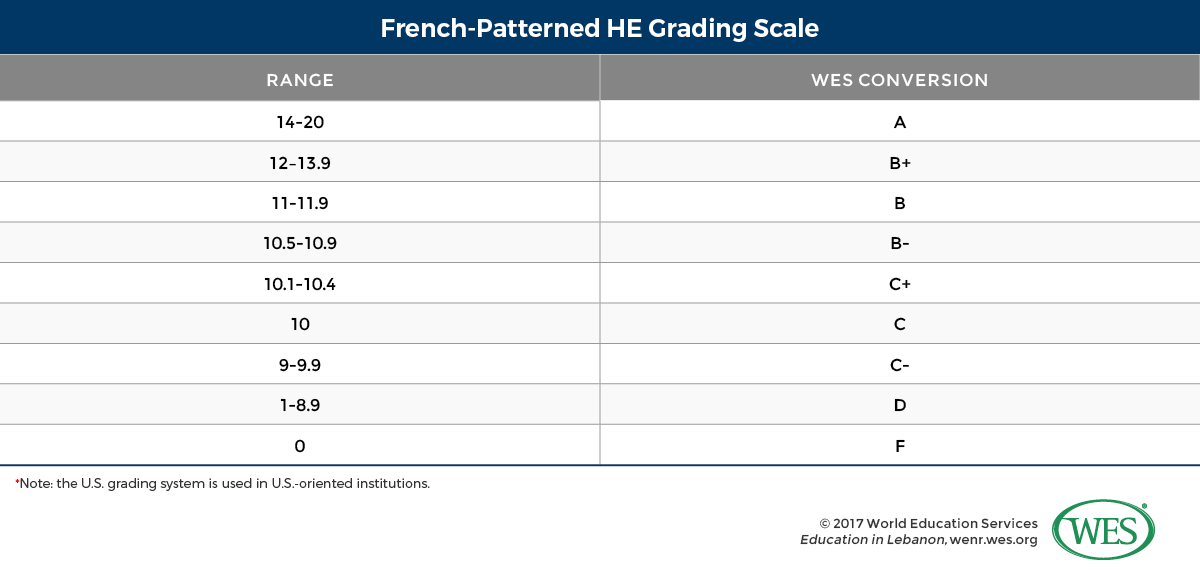

French-patterned institutions use the French grading scale. Below is a table of how WES converts such grades into the American/Canadian equivalents. (NOTE: Some universities indicate ECTS (European Credit Transfer System) credits.)

The American grading system is used in American-patterned institutions.

Master’s Degrees

Masters programs in American-modeled institutions are usually one to two years of study following the bachelor’s degree, leading to a master’s degree [28], usually either a Master of Science or Master of Arts (Master, in French; Majistaire in Arabic).

French-modeled universities [33]offer several master’s-level qualifications. Programs are generally two years in duration (120 ECTS credits).

- The Maîtrise was offered as a four-year program immediately after secondary school, or after one year of study beyond a three-year Licence. (The Maîtrise has largely been discontinued.)

- The Magistère is obtained after two years of study beyond the Licence and, in WES’s experience, is less common.

- The Diplôme d’Etudes Supérieures (DES) is typically achieved one to two years after a Licence, or offered as a five-year program immediately after high school graduation.

- Finally, the Diplôme d’Etudes Supérieures Spécialisées (DESS) is generally a one-year program after four or five years of undergraduate study.

French system-oriented institutions may distinguish between two different types of master’s level degrees [19]: Master de Recherche for more research-oriented master’s degrees or Master Professionnel for more professionally-oriented degrees. Some but not all master’s programs require a final paper.

Doctoral Degrees

Doctoral programs [28] generally last two to five years after completion of a master’s-level degree, culminating in a final thesis (equivalent of a dissertation in the U.S.). These programs are generally research-intensive [33] and lead to a doctoral degree or Doctorat that WES considers equivalent to an earned doctorate in the U.S.

Professional Education

Medical Degrees

The American style medical degree, the Doctor of Medicine, is a four-year program that students typically enter into after completing Bachelor of Science degrees.

French-style medical degrees –dentistry, medicine, and pharmacy degrees – begin immediately after secondary study and are between five and seven years in length.

- The Diplôme de Docteur en Médecine is six years followed by one internship year. WES considers this equivalent to the first professional degree in medicine (Doctor of Medicine).

- The Diplôme de Docteur en Chirurgie Dentaire (Diploma of Doctor in Dental Surgery) follows five years of study, and WES considers this equivalent to five years of professional study in dentistry.

- The Diplôme de Docteur en Pharmacie (Diploma of Doctor in Pharmacy) is five to six years of study, which WES considers equivalent to a combined bachelor’s and master’s degree. Colloquium exams are held twice a year for licensing to practice these professions.

Engineering Degrees

The French-style degree of Diplôme d’Ingénieur (Diploma of Engineering) is a long single-tier program that lasts for five years beyond secondary education. WES equates the degree to bachelor’s and master’s degree levels in both the U.S. and Canada.

U.S.-style institutions offer a five-year Bachelor of Engineering that WES equates to a Bachelor’s degree in the U.S. and a Bachelor’s degree (four years) in Canada. U.S.-patterned institutions also offer two-year Master of Engineering degrees that typically follow a Bachelor of Engineering. These Master of Engineering degrees are considered equivalent to master’s degrees by WES.

Teacher Education and Training

Elementary school teachers [28] are required to receive three years of undergraduate education and practical training at faculties (departments) of education at any university.

- In an American-patterned institution, this culminates in a Bachelor of Arts degree in Education or in Elementary Education. Additionally, students holding a bachelor’s degree in any field can complete an additional year of study and practice to receive a Teaching Diploma (TD) in Elementary Education.

- In French-oriented institutions, students must obtain a Licence en Sciences de l’Education, Licence en Pédagogie, or Diplôme de Technicien Supérieur. They can also receive a Licence d’Enseignement Technique [59], a three or four-year post-secondary program that leads to an examination from the Ministry and a bachelor’s level credential. This allows the holder to teach in technical fields such as engineering or mechanics.

Secondary school teachers [16] can receive a Teaching Diploma (TD) after one year of study following the bachelor’s degree.

- At French-oriented institutions, acceptable degrees for the secondary school level are Licence en sciences de l’education and Licence en Pédagogie – both three-year programs – and the Diplome d’Études Supérieures (DES), a two-year master’s-level program.

- Students at the Lebanese University can partake in a five-year program [28] in the Faculty of Education culminating in a degree called the Certificat d’Aptitude Pédagogique de l’Enseignement Secondaire.

Documentation Requirements

WES has specific document requirements for both secondary and post-secondary study in Lebanon.

Secondary Education

WES requires clear legible photocopies of all graduation certificates in the language in which they were issued. Examination results that indicate all subjects taken and grades obtained must be sent directly to WES by the Ministry of National Education. Precise, word-for-word English translations prepared by the institution from which students graduated, or by any certified translation service, are required for all documents that are not issued in English.

Higher Education

WES requires clear legible photocopies of all degree certificates or diplomas issued by the institutions attended. These documents must be in the language in which they were issued. Academic transcripts indicating all subjects taken and grades obtained for all post-secondary programs of study must be sent directly to WES by the institutions attended.

For completed doctoral programs, a letter confirming the awarding of the degree must be sent directly to WES by the institution attended. Precise, word-for-word English translations prepared by your institution or any certified translation service is required for all documents that are not issued in English.

Sample Documents

Click here [60] for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Diplôme de Baccalauréat de l’Enseignement Secondaire – Deuxième Partie (Diploma of Baccalaureate of Secondary Education – Second Part)

- General Secondary Diploma

- Certificate of Graduation

- Diplôme de Technicien Supérieur (Diploma of Higher Technician)

- American University of Beirut – Bachelor of Science

- Notre Dame University – Bachelor of Business Administration

- Lebanese University – Diplôme de Licence (Bachelor’s degree)

- Lebanese University – Diplôme de Master Professionnel (Master’s degree)

References

| ↑1 | “Higher Education in Lebanon,” European Commission for Higher Education, July 2012. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This article includes international student data reported by multiple agencies. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. |

| ↑3 | These numbers reflect both degree seeking students – meaning those captured by UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics – as well as students who are here under different circumstances, for instance, a limited term of study, Optional Practical Training, etc. |

| ↑4 | There are very few reliable data on international students in Lebanon overall, due in part to the fact that all but one of Lebanon’s universities are private, and maintain differing standards for collecting and releasing data. |

| ↑5 | Last updated February 15, 2017. |

| ↑6 | Last updated March 30, 2017. |

| ↑7 | Rough averages are all that is available, as data for the greater Middle East region can be in short supply. |

| began implementing this three cycle structure [16] in their faculties in 2005, though implementation has not been immediate or uniform. | |

| ↑9 | El-Ghali, Hana Addam and Ghalayini, Nadine, “Leveraging the Quality of Higher Education in Lebanon: Study Summary Report.” Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs, American University of Beirut, July 2015 |

| ↑10 | El-Ghali, H. and Ghalayini, N, “Why Doesn’t Lebanon Have a National Quality Assurance Agency Yet?” Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs, American University of Beirut, Policy Brief #4, March 2016. |

| ↑11, ↑12, ↑13 | Higher Education in Lebanon,” European Commission for Higher Education, July 2012. |

| ↑14, ↑15 | ”Education in Lebanon: The Lebanese education system described and compared with the Dutch system,” EP-Nuffic (2016). |

| Bologna Process [57]. |