Wilson Macha, Knowledge Analyst, and Aditi Kadakia, Senior Knowledge Analyst Manager, WES

This article describes current trends in education and international student mobility in South Africa. It includes an overview of the education system, a survey of recent changes and reforms, and a guide to educational institutions and qualifications.

Introduction: An Uneasy Balance

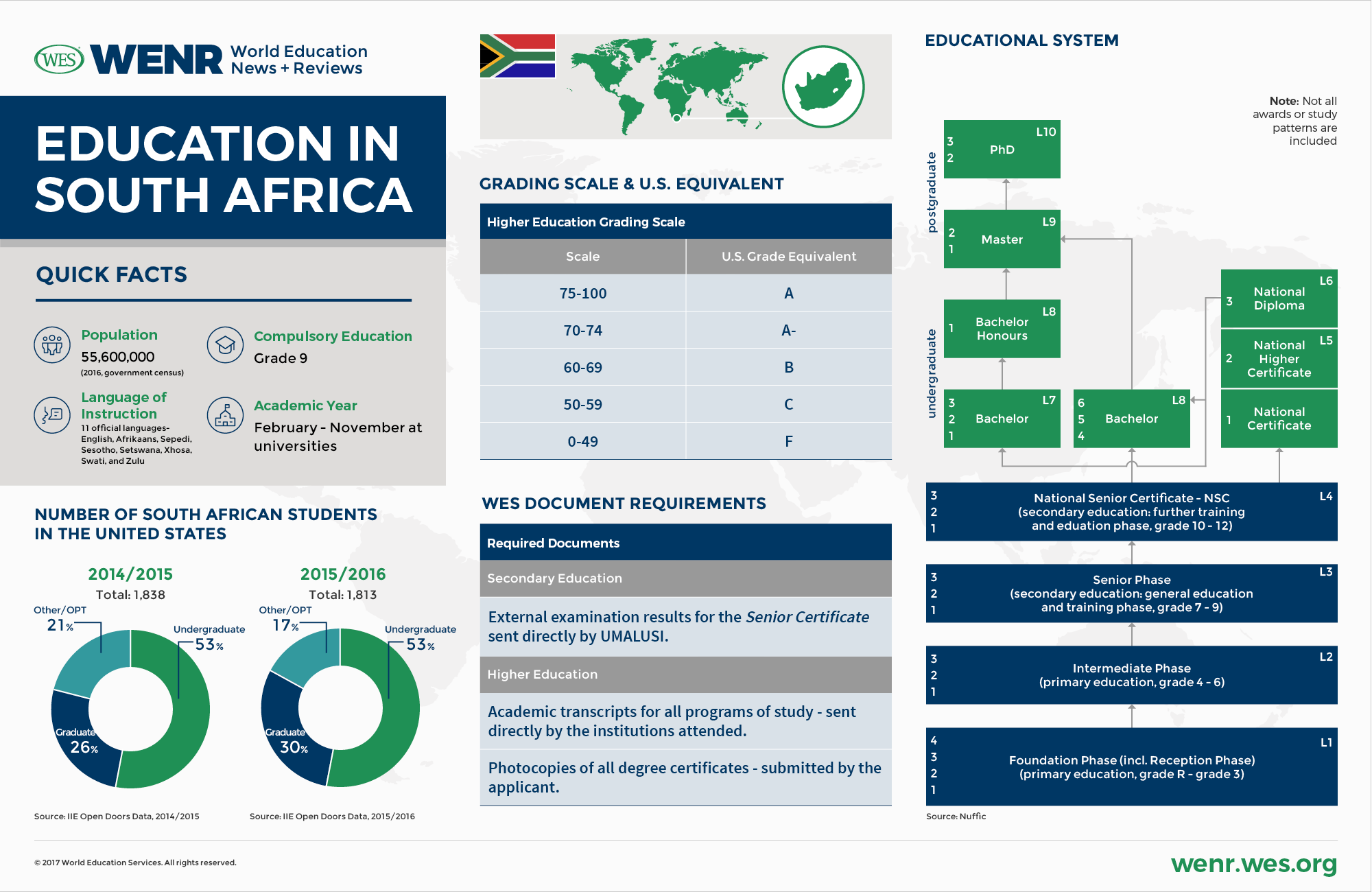

Twenty-three years after the end of apartheid, South Africa remains a country of both promise and discord. With a population 55.6 million (2016, government census) it is, alongside Nigeria, one of the African continent’s two largest economies [3].

It is, as the CIA World Fact Book [4] describes it, “a middle-income, emerging market with an abundant supply of natural resources; well-developed financial, legal, communications, energy, and transport sectors; and a stock exchange that is Africa’s largest and among the top 20 in the world.”

As of mid-2017, however, the country stands at the edge of a knife, both in terms of political stability and economic viability [5]. At the start of April, the country’s credit rating was cut to junk status [6], after President Jacob Zuma, long under a cloud of acrimony [7], abruptly fired his finance minister, along with nine other cabinet members. In 2016, the country’s “economy grew just 0.3 percent … the weakest pace of growth in seven years [8].” At the end of the year, the unemployment rate stood at 26.5 percent overall [9], and was even higher among black youth. As the World Bank notes, the country effectively remains “a dual economy with one of the highest inequality rates in the world.”

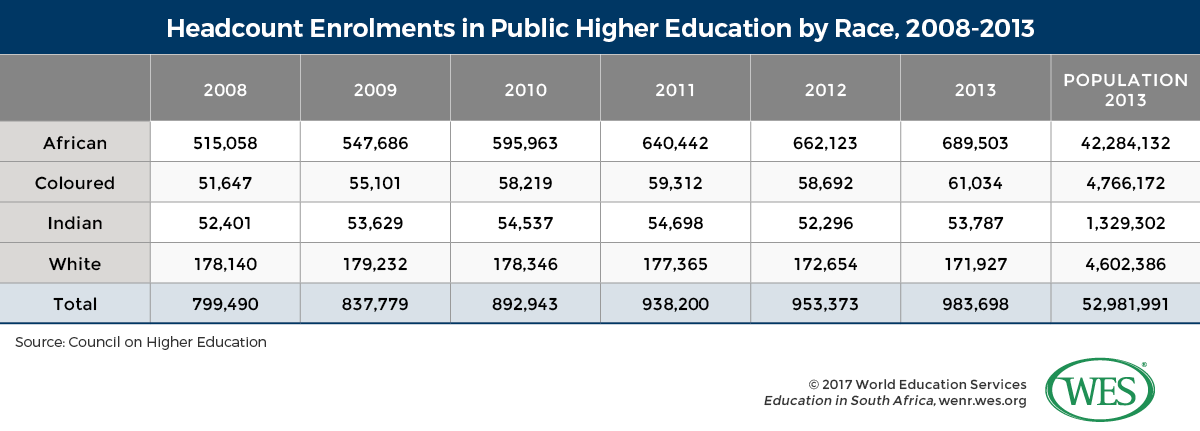

The legacy of South Africa’s apartheid system of government, which lasted from 1948 to 1991, is largely to blame. The country’s education system, in particular, has never fully recovered from the 1953 Bantu education law, which was designed to render the country’s majority black population disenfranchised both from the political system and the economy. The law “deliberately sought to make blacks subservient laborers,” as the New York Times [10] described it. It also systematically excluded black students from exposure to certain subjects.

Today, South Africa invests a considerable amount in education – as it has ever since the end of apartheid. In 2013, for instance, 19.7 percent of the country’s total budget went to education – a relatively high figure by international standards. However, the ripple effect of the discriminatory education system continues, not least on the quality of instruction available from a generation of teachers, themselves educated by a sub-par system.

The progress made to date is still uniformly viewed as insufficient to the needs of the country and its black majority population, and the education system is still, by any objective standard, failing both students and the country. As per The Economist [12], South Africa is “75th out of 76 [countries in a 2015 OECD ranking]…

In November [2016] the latest Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), a quadrennial test sat by 580,000 pupils in 57 countries, had South Africa at or near the bottom of its various rankings …. A shocking 27 percent of pupils who have attended school for six years cannot read, compared with four percent in Tanzania, and 19 percent in Zimbabwe. After five years of school about half cannot work out that 24 divided by three is eight. Only 37 percent of children starting school go on to pass the matriculation exam; just four percent earn a degree… The gap in test scores between the top 20 percent of schools and the rest is wider than in almost every other country. Of 200 black pupils who start school just one can expect to do well enough to study engineering. Ten white kids can expect the same result.”

A rural-urban split in attainment is also acute. According to one 2015 report [13], 41 percent of sixth grade students in rural schools were reportedly functionally illiterate in 2007 compared to only 13 percent of their urban counterparts. Educational resources and infrastructure also vary radically by location, with children in rural areas often attending schools that lack basics like electricity, running water, or books. The fact that South Africa has 11 official languages further complicates matters, and achievement at the secondary varies widely by province.

At the tertiary level, deep divides between the country’s top-performing and lowest-level institutions remain, as do overwhelming gaps in the rates of whites and non-whites who obtain tertiary-level degrees. Simmering resentments have recently spilled over. University protests in opposition to everything ranging from rising tuition, as seen in the #feesmustfall movement, to physical reminders of South African’s colonial past (see #Rhodesmustfall) have shut down campuses, led to millions of dollars in damages, and affected inbound mobility to South Africa, and threatened the ability of researchers to complete their work on campus.

Still, years of sustained government investment in education have had a real impact. “Black youth [now] have higher educational attainment now than at any point in South Africa’s history,” scholar and South African education expert Nic Spaull has noted [14]. “Between 1994 and 2014 the number of black graduates with degrees being produced each year … more than quadrupled, from about 11,339 (in 1994) to 20,513 (in 2004) to 48,686 graduates (in 2014). [From] 2004 and 2014, [the number of] black graduates increased by about 137 percent (compared to 9 percent for whites), while the black population grew by about 16 percent.”https://mg.co.za/article/2016-05-17-black-graduate-numbers-are-up [15]

Technical and Vocational Training: A Priority Focus

South Africa’s Department of Higher Education and Training, which oversees the country’s entire tertiary sector, frames vocational training as a critical – and underfunded – part of South Africa’s post-secondary education ecosystem, and as crucial to the nation’s economic well-being. “About one million young individuals exit the schooling system annually,” notes the department’s strategic plan for fiscal years 2015/16 – 2019/20 [16]. “However, only a small number of those who leave the schooling system [enroll] in TVET colleges or have access to any Post-School Education and Training [and the few who do] … are not sufficiently prepared for the workplace due to the poor quality of education and training provided.” The net, says DHET, is that the existing TVET system “is not able to produce the number and quality of graduates needed by the economy.”

International Student Mobility: Inbound and Outbound Trends

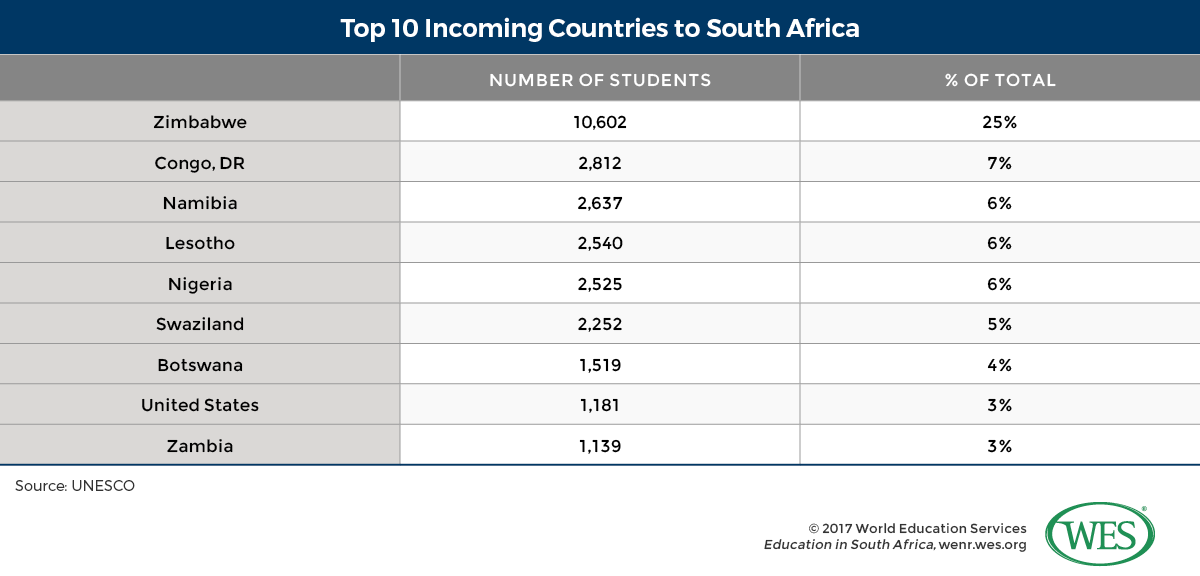

Despite its weaknesses, South Africa’s tertiary education system is the most extensive and highest quality on the African continent. It attracts more international students than any other African nation. Data from UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics [17] (UIS) indicates that some 42,594 international students sought degrees in South Africa in 2014. The vast majority are from other African countries. The same year, just 7,395 South African students sought degrees abroad [17].[2]A note on source data: Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies.

Inbound Mobility

As of 2014, South Africa was the fourth most popular destination for internationally mobile degree seekers from across Africa [18], behind France, the U.S., and the U.K. The largest sender by far is Zimbabwe, which, per UIS, sent a reported 10,602 degree-seeking students to South Africa in 2014. Other top countries of origin include Democratic Republic of Congo, Namibia, Lesotho, Nigeria, and Swaziland, each of which accounted for more than 2,000 enrollments in 2014. The low cost and relatively high quality of these institutions is likely one factor.

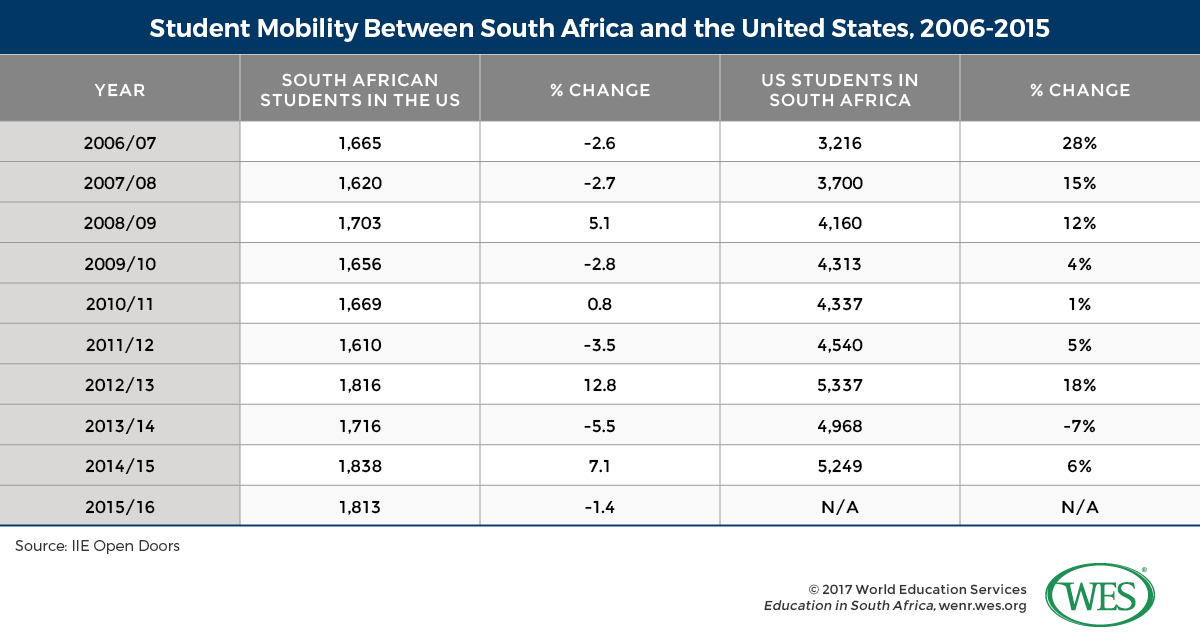

The only non-African country of origin among the top ten senders is the United States. According to IIE’s Open Doors [19]report for 2015/16, South Africa was the eleventh leading destination for U.S. study abroad participants. That year, some 5,337 American students studied on South African campuses, 17.6 percent more than the previous year.

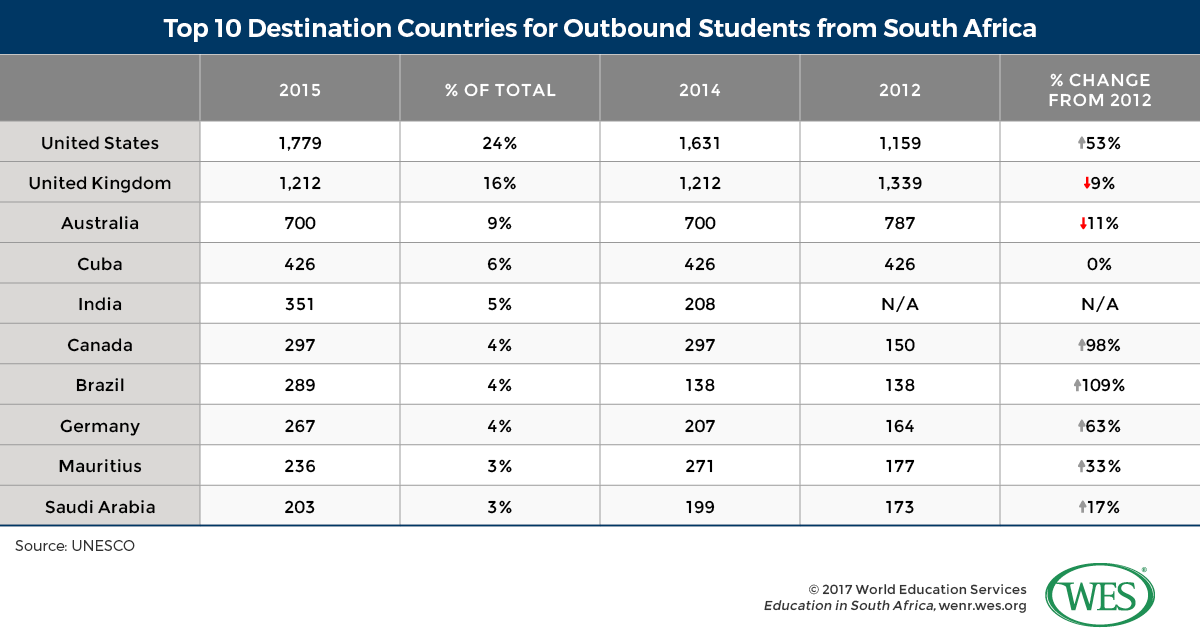

Outbound Mobility

Outbound mobility among South African students tends to be low. The 7,395 who sought degrees abroad in 2015, represented about 0.1 percent of the country’s tertiary-age population, and only 1 percent [21] of its total tertiary enrollment.

Almost half of South African students abroad chose English-speaking host countries, including the U.S., the U.K., and Australia. The U.S. has been the leading destination for South African students over the years, with the volume remaining relatively stable over the last decade. The majority of South African students in the U.S. – 57 percent in 2014 [22] – are enrolled at the undergraduate level. Twenty-nine percent were pursuing graduate degrees.

A Deeper Look at Inbound Mobility: Why Students Come to South Africa, and What Might Keep Them Away

A 2014 survey [25] of almost 1,700 South African-enrolled students from countries in Southern African Development Community [26] represents one of the few research efforts to examine, in depth, the reasons that tertiary-level students from other African countries come to South Africa. Survey responses and follow up interviews indicated that top draws were affordability, proximity, ease of visa approval, “the reputation of the South African higher education system, the ‘currency’ of South African qualifications [in terms of job prospects back home], flexible admission policies, the lack of the preferred course in the home country, a stable and peaceful academic environment, and diversification of the academic experience.”http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20140905134914811 [27]

Since 2014, however, both visa challenges and recurrent campus-based protests at dozens of universities have cast a pall on South Africa’s lure as a study destination. Changes to South Africa’s immigration laws have also had an impact [28] on in-bound numbers. International enrollments in English language learning schools plummeted by 37 percent [29] from 2014 to 2015, and other students suffered long delays and sometimes outright refusals of visa approvals [30].

South African campuses, meanwhile, have been wracked by violence. In 2015, the historically white University of the Witwatersrand announced that it would raise tuition fees by 10.5 percent [31]. The institution was just one of many affected by system-wide budget shortfalls that raised the specter of more widespread fee increases. The funding crises occurred amid often failed efforts to address deep racial disparities that have left many students of color, often from poorer backgrounds, cut out of South Africa’s higher education system.

Combined, these factors created a perfect storm: protests that began on the Witwatersrand campus in the fall of 2015 sparked a far-broader campus-based movement, called Fees Must Fall, characterized by often violent protests. The situation has affected most of the country’s 26 public universities. At one point in 2016, 17 were not fully operational, and the University of Limpopo in the north was closed indefinitely. Top universities, including the Witwatersrand, the University of Cape Town, and the University of Johannesburg, were also deeply affected. Campus protests [32]injured dozens, claimed at least one life, and led to arson and tens of millions of dollars in damages.

As of the summer of 2016, 16 of South Africa’s 26 public institutions of higher education faced a nearly USD $279 million budget shortfall [33] for 2017-18. In the fall, the country’s Department of Higher Education and Training announced a decision to allow universities to hike fees by as much as 8 percent, leading to still more protests [34]. The impact of the chaos on international enrollments is not yet clear, but many expect foreign students to look for options other than South Africa [35].

South African Education: Structure and Administration

South Africa’s education system is split into three levels: elementary, secondary and tertiary. Prior to 2009, the National Department of Education [36] was responsible for higher education as well as elementary and secondary education. Since then, oversight has been split to enable greater focus on radically different educational systems, and to increase the government’s focus on post-secondary education. The Department of Basic Education [37] (DBE) now oversees elementary and secondary education. The Department of Higher Education and Training [38] (DHET) oversees post-secondary-level education, including both academic institutions and post-secondary technical training.

The South African government has devoted substantial resources to education in recent years. In 2013, it spent 19.7 percent of its total budget on education – a relatively high figure by international standards, and one that represents about 6 percent of the country’s GDP (2014 [39]). The lion’s share of the national education budget is allotted to the elementary and secondary school systems, which are administered by the provincial governments. In 2013/14, 57.7 percent [40] of funds were devoted to elementary and secondary schooling, although this percentage is expected to drop in favor of increased spending on post-secondary education in the coming years.

Administration of Elementary and Secondary Schools

South Africa’s estimated 26,000 schools and 425,000 educators are overseen by the Department of Basic Education. District and provincial DBE offices in nine provinces [41] and 86 districts administer these schools and have considerable influence over the implementation of policy.

The stated goals [36] of the DBE – and its district and provincial offices – are to:

- improve the quality of teaching

- undertake regular assessments

- improve early childhood development

- ensure a system of outcomes-focused accountability

The DBE’s provincial offices work through local district-level offices to administer elementary and secondary schools. As of 2016/17, the DBE reported that it was working closely with provincial education departments (PEDs) “to assess management at classroom, school, district, and provincial levels… to heighten accountability at all levels of the system.” For the duration of the effort, which is slated to continue through 2020, the DBE seeks to “strengthen … [the] capacity to monitor and support provincial departments… especially in PEDs that performed poorly in the 2015 [National Senior Certificate examination] … to ensure that learning outcomes are improved.”http://www.education.gov.za/ [42]

Elementary and secondary schools in South Africa are most often public, and account for the bulk of enrollments. In 2012, for instance, 4.64 million pupils were enrolled in public secondary schools compared to only 292,331 at private schools, as per data [43] provided by the UIS.http://www.cde.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/LOW-FEE-PRIVATE-SCHOOLS.pdf [44] However, independent private schools exist in South Africa have recently gained some traction as an alternative to struggling public schools. “Low-fee” independent schools cater to lower income households, and are eligible for government subsidies. Although still low by comparison to the public system, enrollments in these and other private schools have risen substantially in recent years [45].

Administration of Post-Secondary Institutions

Administration of post-secondary education is the responsibility of the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). When the DHET was formed in 2009, it took over administration of higher education as well as some vocational and technical training, an area previously under the Department of Labour. DHET’s new, combined portfolio stemmed from efforts to make post-secondary education more accessible – and to build a more highly skilled workforce – through two mechanisms: an increase in the number of vocational schools and a more plentiful budget for financial aid.

The Department of Higher Education and Training receives a far smaller budget than the Department of Basic Education. As of 2015, the government estimated that, on average, 14.9 per cent of the total education budget [40] was allocated to higher education and training between 2010 and 2017. Although this percentage is far smaller than that allocated to the DBE, the DHET budget has grown each year [40] and is projected to continue doing so.

Under the DHET’s watch, enrollment in both tertiary and technical/vocational post-secondary education (TVET) has increased considerably. Enrollments at university-level institutions increased by 13 percent between 2010 and 2014, from 983,703 to approximately 1.1 million students [46]. In the TVET sector, enrollment almost doubled from 405,275 students in 2010 to 781,378 in 2014 [46].

South African Education: Elementary and Secondary Levels

Elementary Schooling: The Basics

Elementary education in South Africa lasts seven years, and requires the completion of grades R (or reception year, which is equivalent to kindergarten) through grade 6. This phase is further divided into two parts, the foundation phase and intermediate phase. Students begin elementary school at six years of age.

- The foundation phase consists of grades R through three, and focuses on subjects such as home language, an additional language, mathematics, and life skills. There are in total between 23-25 hours per week taught in the classroom. The additional official language subject is introduced in grade one.

- The intermediate phase includes grades four to six. The curriculum includes a home language, an additional national language, mathematics, natural science and technology, social sciences, and life sciences. Students in the intermediate phase attend classes 27.5 hours per week.

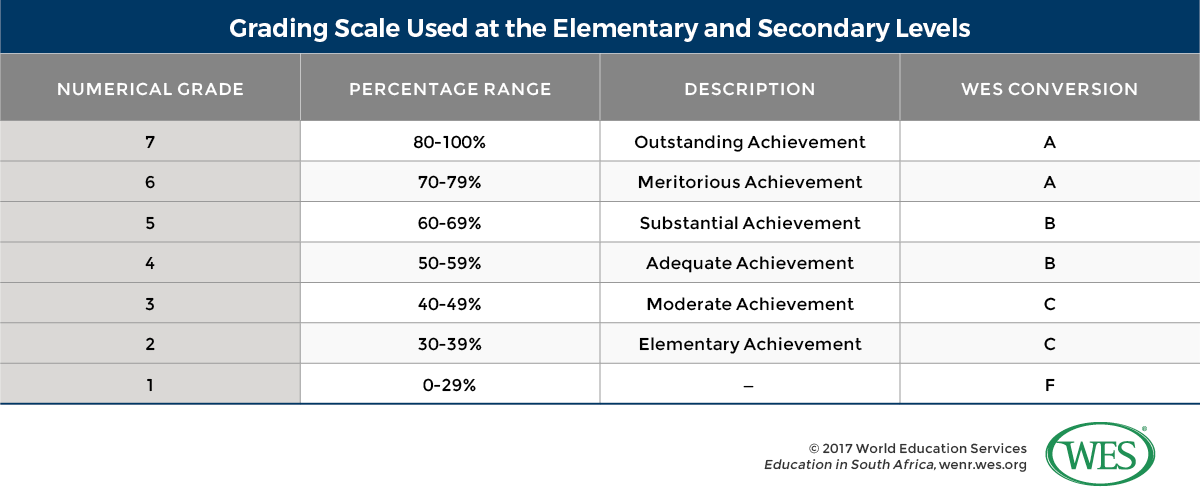

A number of achievement levels, ranging from 1 to 7, are used to evaluate students’ learning. The lowest achievement level – level 1 – represents a failing grade denoted as “not achieved”, whereas the highest achievement level 7 denotes “outstanding achievement.” These achievement levels also correspond to a 0-100 percentage scale.

Assessment at the elementary level is conducted by each individual elementary school. There are no national examinations, nor is there a formal qualification awarded at the end of the elementary school cycle.

Participation and Quality Constraints at the Elementary Level

Overall enrollment levels in elementary education have increased tremendously in recent years, and the South African government has stated [48] that it is on track to achieve its goal of reaching an enrollment rate of 100 percent in the first year of schooling (reception year) by 2014. Between 2003 and 2013, new annual enrollments in grade R doubled, from 300,000 to 705,000 pupils, according to the numbers provided [48] by the government.

However, the poor quality of education remains a constant theme in South Africa. Despite increased education spending and enrollment levels, South Africa continues to be considered one of the worst education systems [49] in the world. South African students perform poorly compared to students from other countries at comparable levels of development, and dropout rates in schooling are high. According to media reports [50], about 20 percent of children in elementary and secondary school failed their final year-end school examination in 2015, and only about half [51] of all pupils who entered elementary education continue on to pass the final school-leaving examination 12 years later.

Race, Poverty, and Academic Achievement in South Africa

Racial inequality plays an important role in determining educational achievement. According to the education researcher Nic Spaull, “only 44 percent of black and coloured youth aged 23-24 attained …[upper-secondary education] compared to 83 percent of Indian youth and 88 percent of white youth”.or more than 90% of the country’s poverty share [52]”

In recent years, a number of government-subsidized, “low-cost” private schools have opened, in an effort to provide high-quality options [53] to impoverished students in black communities, informal settlements, and urban slums. The curricula at low-fee private schools can be more demanding than public school curricula, and parents often perceive private schools as a better option [53] for their children.

The effectiveness of the private schools is, however, a hotly debated topic in South Africa. While proponents argue that a market-based system does increase educational quality, others object to privatization [54]. As of 2015, an estimated four percent of South African students were in private or independent schools; and an estimated seven percent of schools were independent.[7]Spaull, Nic. “For-profit schooling in SA: An overview and discussion for the IEB.” September 2, 2015. Retrieved from https://nicspaull.com/presentations/

Secondary Education: The Basics

Secondary education in South Africa is six years in duration (grades 7 to 12), and is divided into two phases, lower and upper secondary school.

- Lower secondary (also known as the “senior phase”) lasts through grade 9, and is mandatory. Students typically begin lower secondary at age 12 or 13. The curriculum for lower secondary school includes the home language, an additional language, mathematics, natural science, social science, technology, economic and management sciences, life orientation, and arts and culture. Students receive 27.5 hours of classroom instruction per week.

- Upper secondary, also known as further education and training (FET), lasts through grade 12, and is not compulsory. Entry into this phase requires an official record of completion of grade nine. Just as in the intermediate and senior phases, this phase comprises 27.5 classroom hours per week.

At the start of upper secondary school in grade 10, students are streamed into one of two tracks – academic (general) or technical. Students who select the technical track must be enrolled in a technical secondary school.

In both academic (general) and technical routes all students must study seven subjects. Four subjects are mandatory regardless of stream. These include two official languages, mathematics (mathematics courses differ in scope between the two tracks), and life orientation. Students can select the remaining three subjects as electives. Students are advised to study subjects that they might be interested in pursuing in higher education.

Graduation depends on performance on a final exam, the National Senior Certificate or “matric,” at the end of grade 12. Those who earn a second level or “higher certificate” pass (described below), but who do not score high enough to continue on into diploma or degree-granting institutions of higher education may enroll in a bridge year, or grade 13, at an accredited institution.

NOTE: Drop out numbers at the secondary level, particularly in the final year, are high. According to DHET, “About one million young individuals exit the schooling system annually, many … without achieving a Grade 12 certificate. Half of those who exit the schooling system do so after Grade 11, either because they do not [enroll] in Grade 12 or they fail Grade 12.”[8]Department of Higher Education, Strategic Plan for Fiscal Years, 2015/16- 2019/20, p. 16. (Additional detail below.)

Examinations: The National Senior Certificate and the Independent Examinations Board

The National Senior Certificate (NSC) or “matric” is a national, standardized examination, which represents the final exit qualification at the end of Grade 12. The NSC replaced an earlier exam known as the Senior Certificate.[9]In 2008, the NSC replaced the Senior Certificate as the final school-leaving certificate. Students can earn one of four levels of pass when they sit for the matric. If their scores are high enough, the test qualifies them for higher education.

From lowest to highest. the four levels include:

- A certificate pass: Per the South African Council for Quality Assurance in General and Further Education and Training (Umalusi), the NSC pass is a “baseline” that “serves little purpose other than providing the learner with a school leaving certificate, and perhaps signaling to employers that a basic level of home language competence and numeracy have been achieved.”http://www.UMALUSI.org.za/docs/research/2013/nsc_pass.pdf [55], accessed April 2017. To obtain an NSC pass, students must pass three subjects – including home language – with a minimum pass mark of 40 percent; and three with a minimum pass mark of 30 percent. Six out of seven subjects must be passed in order for students to receive an NSC pass.

- A higher certificate pass: This second tier of pass does not qualify students for all types of post-secondary education, however it does enable access to certification programs [56] that will prepare them for the work force, or with access to academic “bridge programs” – year 13 – offered by accredited institutions.

- A diploma pass: A diploma pass is the third tier of NSC pass. It is the minimum requirement for entry into tertiary level programs that grant diplomas rather than full degrees.

- A bachelor’s pass: A bachelor’s pass is the highest level of NSC pass. It represents the minimum requirement for admission to bachelor’s degree programs at South African universities. Universities may set minimum score requirement scores that are higher than the legal minimum pass. Certain programs may only accept students who achieve high marks in relevant subjects.

Umalusi is responsible for the administration and issuing of these and other educational certificates. Umalusi verifies certificates issued by the Independent Examinations Board (IEB).http://www.UMALUSI.org.za/show.php?id=2894 [57].

The IEB administers exit examinations for private schools. The IEB administers a version of the NSC, which is viewed as a more rigorous assessment than the government-administered version taken by most public school students. A 2009 UK NARIC benchmarking exercise reportedly found that at, some advanced levels, the IEB is comparable [58] to GCE A level standards.

High School Completion: A Complex Picture

Overall upper-secondary attainment rates in South Africa are higher than in many sub-Saharan countries, and have increased considerably in recent years – between 2005 and 2015 the percentage of South Africans older than 25 with upper-secondary attainment increased from 39.6 to 48.5 percent, according to the UIS [59]. Participation and progression rates nonetheless remain problematic, and are below those of other countries at comparable levels of economic development.

Official statistics on student achievement can be confusing. According to the South African government, for instance, the overall pass rate in the 2013 NSC examinations was 78.2 percent [48], with 439,779 out of 562,112 pupils passing the exam. Due to high drop-out rates however, between the senior and matriculation phases, this relatively high pass rate masks low upper-secondary completion rates. One 2015 study [13] found that about 50 percent of upper-secondary students dropped out of school before graduation, mainly in grades 10 and 11.

Moreover, only slightly more than one third of those students who pass the final matriculation examination presently achieve sufficiently high grades to be admitted to university, and not all of these students end up being accepted.19.4 percent [43]. High dropout rates at the secondary level are mirrored at the tertiary level, where reportedly only half of those that initially enrolled go on to eventually graduate.[13]Ibid., 36.

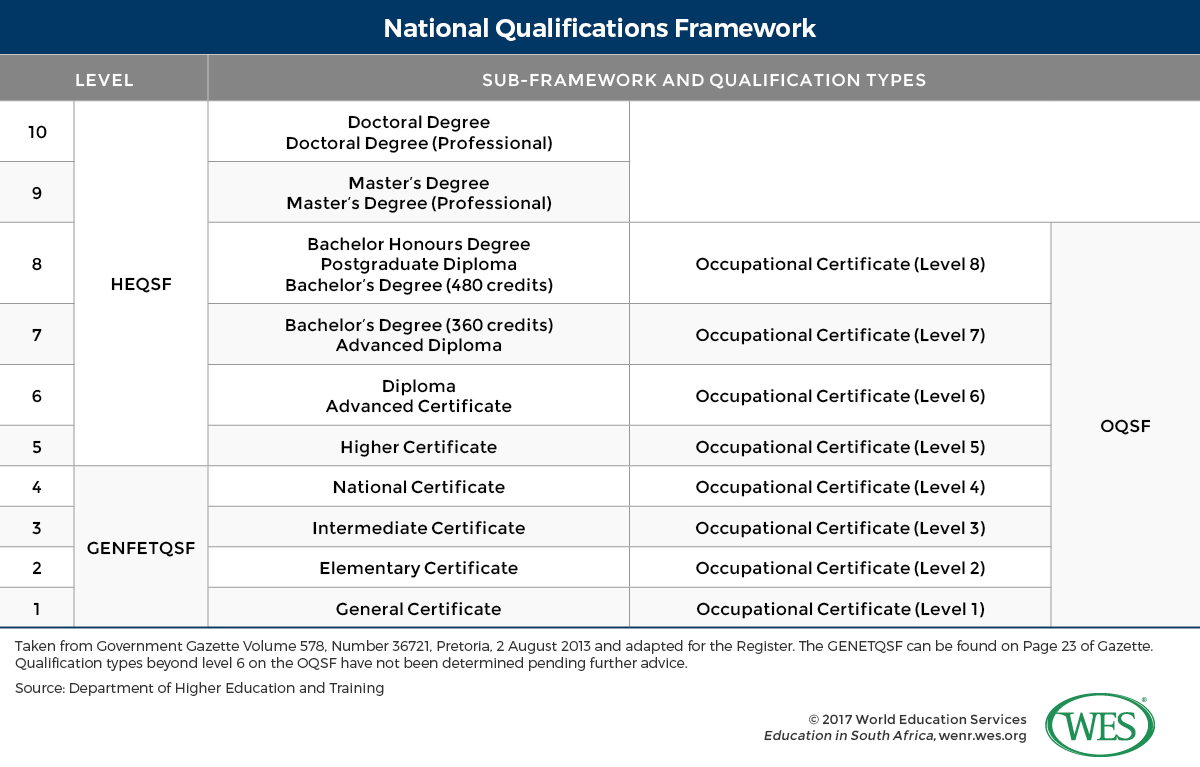

South Africa employs a National Qualifications Framework (NQF), which defines benchmark requirements and goals for all levels of the education system. Initiated in 1995, the framework originally included eight levels [60]. Two were added in 2008, meaning there are now a total of 10 levels. These levels are tightly linked to every phase of education in the country. Each level corresponds to a “level descriptor [61],” which outlines the specific scope of qualifications achieved at each level. The levels are divided into three “sub-frameworks” which span general education, higher education and occupational training. These are the: The first two sub-frameworks represent a linear trajectory from elementary education (level 1) through doctoral study (level 10). The Occupational Qualifications Sub-Framework ends at level 6, though optional level 7 and 8 qualifications may be offered through “collaboration with a recognized professional body and the Council on Higher Education”.http://www.saqa.org.za/list.php?e=NQF [63].

National Qualifications Framework

The national qualifications framework lists the minimum credits required for the award of a degree or qualification at each level. One credit is defined as 10 “notional” study hours.On average, one week represents about 40 notional study hours.University of Stellenbosch [64], notional learning hours are “the estimated learning time taken by the ‘average’ student to achieve the specified learning outcomes of the course-unit or programme. They are therefore not a precise measure but provide students with an indication of the amount of study and degree of commitment expected. Notional learning time includes teaching contact time (lectures, seminars, tutorials, laboratory practicals, workshops, fieldwork etc.), time spent on preparing and carrying out formative and summative assessments (written coursework, oral presentations, exams etc.) and time spent on private study, whether in term-time or the vacations.”

Typically, university undergraduate programs require 30 weeks of full-time study a year. Graduate programs, such as master’s and doctoral degrees, require 45 weeks of full-time study a year.[xxxvii] [65]

NOTE: Even though there is a minimum credit requirement, individual universities are allowed to set their own curricula, which can exceed the minimum.

Higher Education: TVET and Academic Institutions

As at upper secondary level, post-secondary education in South Africa includes both an academically oriented university track and a vocationally oriented technical track.

Technical Education

Given high youth unemployment rates, technical and vocational training (TVET) is of key strategic importance to South Africa’s economy and political stability. TVET training is offered at both public and private technical colleges. In 2014, there were 50 public and 291 private TVET colleges in South Africa. Generally, both public and private TVET institutions offer the same types of qualifications, which may be either national certificates to national diplomas. The difference between the two types of institutions comes from the source of funding. The private institutions are, of course, funded privately with the possibility of partial government subsidies, where the public TVET institutions are funded by so-called “Sector Education Training and Authorities” (SETAs) [46].

As of 2014, there were 781,378 students [46] enrolled in TVET institutions; only about eleven percent of these students (78,955) were attending private institutions. Public institutions are often larger and in 2016 maintained 264 campuses [66] across South Africa. Further expansion of the public TVET sector is a priority of the South African government and the DHET in 2015 took over the administration of 50 of public TVET institutions in an attempt to advance TVET and address economic needs [66] for skilled labor.

At the post-secondary level, the benchmark qualifications are the Higher Certificate (NQF Level 5), Advanced Certificates (Level 6), and National Diplomas (Level 5 or 6).http://www.dhet.gov.za/ [67] – Pages 8-9In practice, the names and levels of credentials issued in South Africa do not always correspond to these ideal-type benchmark qualifications – a fact that can make the assessment of these credential challenging.

Each of the qualifications can be obtained via different routes; for instance, a Level 6 qualification program can be entered directly after a student earns the a level 2 National Senior Certificate. Generally, however, each NQF level corresponds to a year of study, with a few exceptions, in a semi-laddered structure culminating in the three-year (360 credit) National Diploma.

After the National Diploma there is a Level 7 Advanced Diploma. This qualification straddles the line between academic and vocational education, meaning that it can be utilized either for career advancement or academic enrichment, not that these two are mutually exclusive.

Credential Evaluation Note: What’s a Technikon?

Technikons were public vocational institutions that offered National Certificates and Diplomas up until 1993 when they were authorized to award full-fledged degrees. In 2002, the government started to phase out these institutions and replaced them with Universities of technology and so-called “Comprehensive universities.” Universities of technology are mergers of several of the old Technikons into one institution. These schools offer a variety of applied degree programs, ranging from the National Certificate to the Doctor of Technology.

Universities of technology can only offer applied degrees. Comprehensive universities, on the other hand, are mergers between Technikons and traditional universities and can offer [68] programs and degrees in the traditional arts and sciences, in addition to the applied programs offered by Technikons/Universities of technology. Comprehensive universities were created to strengthen applied research, increase access [68] to technical higher education throughout the country, and facilitate mobility between different types of academic and technical programs.

Academic Education: Universities

Overall enrollments in higher education have more than doubled since the end of the apartheid system in South Africa in 1994, when a reported 495,000 students [69] were enrolled in higher education. A significant part of enrollment gains occurred in distance education programs – 372,331 students [46], or about one third of the 969,155 students enrolled at public universities in 2014, were studying in distance education mode. The University of South Africa, a dedicated distance education provider, is not only the largest university in South Africa with an enrollment of more than 300,000 students, but also the largest university on the African continent.

In recent years, the number of higher education institutions in South Africa has increased, particularly in the private sector. In 2014, there were 26 public universities in South Africa, including 14 traditional research universities, six universities of technology, and six comprehensive universities. (The latter combine the roles of traditional and technological institutions.) In addition, there were as many as 119 private higher education institutions [46], including a number of theological seminaries.

However, the number of private universities in South Africa has remained somewhat limited during the post-Apartheid period, even as the country’s private sector overall saw expansive growth.2014 [46], only less than 13 percent of students were enrolled at private institutions (142,557 out of a total of 1.11 million students enrolled in higher education.) This situation stands in contrast to that of other developing countries, where the deterioration of conditions at public universities has created market opportunities for better-funded private universities.

South Africa’s public universities dominate regional rankings. In 2016, the University of Cape Town led the Times Higher Education [70]list of the best universities in Africa. The University of the Witwatersrand came in second, Stellenbosch University in third, the University of KwaZulu-Natal in fifth, and the University of Pretoria in sixth place.

Observers have noted [71] that black South Africans continue to be underrepresented at these top-tier institutions, which have traditionally served the country’s white minority.

Black students are also under-represented in master’s and Ph.D. programs. That said, black South Africans have made significant progress in closing at least some of the educational attainment gap in the years since the end of apartheid. The number of black students reportedly [72] increased from 59 percent of all university enrollments in 2000 to 71 percent in 2015. Efforts to improvove upon this progress are ongoing. In 2011, the government released a National Development Plan for 2030, and the country’s minister of science and technology announced plans to better fund doctoral programs [73], graduate and mentor more doctoral students, and increase participation by underrepresented groups, including both blacks and women, increasing the proportion of black researchers from 28 percent in 2014 to 40 percent in 2016-17 and women from 36 to 50 percent.

Higher Education: Accreditation

Quality assurance in South African higher education involves institutional oversight and program-based accreditation under the auspices of the Council on Higher Education (CHE) and the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA).

As per the current legislative framework, the Higher Education Act of 1997 [74], the CHE is tasked with setting the quality standards which must be met by institutions seeking accreditation. Through its Higher Education Quality Committee it audits the quality assurance mechanisms of higher education institutions and accredits higher education programs. According to the official Accreditation Framework [75] of the CHE, degree programs offered at South African universities must generally be accredited “based on shared and standard criteria that focus on input, process and output aspects of programmes.”

Private institutions used to be exempted from these requirements, but since 1999 have had to be registered by the national Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET), and offer accredited programs. Under the current system, accreditation of one- and two-year programs lasts for three years. Programs with a duration of three years or longer are accredited for six years.

While the CHE sets overall policy guidelines at the national level, the SAQA is tasked with the implementation of many of these guidelines. The SAQA defines the levels of the National Quality Framework (NQF), ensures their implementation, and manages the registration of qualifications within their appropriate sub-qualifications frameworks. The SAQA also accredits and oversees the so-called “Education and Training Quality Assurance” bodies (ETQAs) – organizations which, in turn, accredit education providers within specific disciplines. ETQAs include professional associations like the Engineering Council of South Africa [76], as well as “Sector Education and Training Authorities” (SETAs [77]) tasked with overseeing skills training in different sectors of the South African economy.

Degrees

Bachelor’s Degrees

Students who obtain a “bachelor’s pass” on the National Senior Certificate examination have the right to be admitted to university, but some institutions have additional admission tests or other entrance requirements.

Bachelor’s degrees are usually three or four years in length. Three-year bachelor’s degrees are in fields such as humanities, business, or science. Examples include the Bachelor of Science, Bachelor of Commerce, Bachelor of Arts, and Bachelor of Social Science. The academic year is 30 full-time weeks; each week students are expected to study 40 hours.

A three-year bachelor’s degree requires a minimum of 360 credits. The final award is at the NQF level of 7. Graduates wishing to continue to postgraduate study will have to complete an additional year of NQF level 8 courses. This can be done through a bachelor’s honors degree or a postgraduate diploma.

Four-year bachelor’s degrees are typically awarded in professional fields such as engineering, agriculture, pharmacy, technology, and nursing. The admission requirements are the same as those for the three-year bachelor’s degrees. These bachelor’s degrees are benchmarked at NQF level 8. They require at least 480 credits.

Honors degrees build on the proficiency acquired in the previous three-year bachelor’s degree. Honors degrees are at the NQF level 8. It is important to note that the “honors” designation in this case does not represent a degree classification, however,it is additional study that is undertaken after the three-year bachelor’s degree. The program is one year in length, yielding 120 credits, and must include a research paper or thesis. The purpose of these programs is to expand the knowledge of the student in a particular area.

In addition to the level 8 honors degrees, there are also postgraduate diplomas that are generally pegged at level eight. Qualifications at different levels can be accessed in the South African Qualifications Authorities’ database [78].

Master’s Degrees

Master’s degrees are benchmarked at level 9 of the NQF. Admission is contingent upon either a four-year bachelor’s degree or a bachelor’s honors degree. Typically, master’s degrees require 180 credits, and entail a minimum completion time of one year. However, requirements can fluctuate between 120 and 240 credits depending on the program.

Students in master’s degree programs are required to complete substantial research. Research can make up the entirety of the program or it can be in addition to coursework.

Doctoral Degrees

The highest qualification offered in South Africa is the doctoral degree. As such, it is pegged at a level ten, the highest level on the NQF scale. Admission to a doctoral degree is dependent upon the completion of a master’s degree. The doctoral degree, or Doctor of Philosophy, typically requires 360 credits and takes a minimum of two years to complete. The 360 credits required for these programs are usually purely based on research, although course work may be required in some programs.

Professional Degrees

The standard degree for medical education in South Africa is the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) or, in Latin, the Medicinae Baccalaureus, Baccalaureus Chirurgiae (MBBCh). It is a six-year degree program directly after the National Senior Certificate.

An alternative to the MBBS is the GEMP or Graduate Entry Medical Program. This program was created by University of the Witwatersrand “to address the current shortage of well-educated and highly skilled doctors [79]”. Under this scheme, students who have completed an undergraduate degree are eligible to enter directly into the third year of an MBBS program, shortening the length of the program to four years. After the completion of the degree a potential doctor must register with the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA). Registration requirements and functions are described in the Health Professions Act of 1974 [80].

In order to become a lawyer in South Africa a student must complete a four-year Bachelor of Laws (LLB). After the completion of the LLB, graduates must complete either six months of service or a six month program at a School for Legal Practice before taking the Law Society examination, which covers practice and procedure, wills and estates, attorney’s practice, contracts and rules of conduct, and legal bookkeeping [81]. To take the examination the examinee must register with their provincial law society. These are the Law Society of the Norther Provinces, the Cape Law Society, the KwaZulu-Natal Law Society and the Law Society of the Free State. After meeting these requirements the registered graduate is free to practice law.

Teacher Education

South Africa is currently experiencing a shortage of teachers. According to one study [82], the country is in need of as many as 30,000 additional teachers by 2025. The government has invested heavily in teacher training, and more than doubled the number of annual graduates from teaching programs from 5,939 in 2008 to 13,708 in 2012. DHET projects [16] that public universities will graduate more than 20,000 new teachers a year by 2019.

The standard requirement for these new teachers is a Bachelor of Education degree – a credential that is typically earned upon completion of four-year university program, including a one-year teaching internship. Alternatively, holders of a three-or four-year non-teaching bachelor’s degree can study for a one-year post-secondary Advanced Diploma in Education (also known as Postgraduate Certificate in Education).

After completing the necessary training, all potential teachers must register with the South African Council for Educators (SACE [83]). Registered teachers are required to pay a monthly fee and follow a code of ethics [84]; failure to meet these requirements will result in the termination of their registration. A number of lower-level teaching qualifications, such the Certificate in Education and the Diploma in Education are awarded by universities, mainly as exit qualifications in incomplete bachelor’s programs, but presently do not entitle to teach in South Africa.

Document Requirements

Secondary Education

WES requires that all external examination results for the National Senior Certificate (or its predecessor, the Senior Certificate) be sent directly to WES by Umalusi [85] (the South African Council for Quality Assurance in General and Further Education and Training). Results must be sent by Umalusi regardless of the accredited assessment agency that oversees administration of the examination.

Higher Education

Required documents include:

- Photocopies of all degree certificates or diplomas issued in English by the institutions attended – submitted by the applicant.

- Academic transcripts issued in English for all post-secondary programs of study – sent directly to WES by the institutions attended.

For doctoral programs without coursework, a letter confirming the awarding of doctorate must be sent directly to WES by the institutions attended.

Sample Documents

Click here [86] for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- National Senior Certificate

- Bachelor of Arts/Bachelor of Arts (Honors) – Academic Transcript

- Bachelor of Arts – Degree Certificate

- Bachelor of Arts (Honors) – Degree Certificate

- Bachelor of Social Work – Academic Transcript

- Bachelor of Social Work – Degree Certificate

- Postgraduate Diploma – Academic Transcript

- Postgraduate Diploma – Degree Certificate

- Master of Science – Academic Transcript

- Master of Science – Degree Certificate

- National Diploma/Bachelor of Technology – Academic Transcript

- National Diploma – Degree Certificate

- Bachelor of Technology – Degree Certificate

- Doctor of Philosophy – Academic Transcript

- Doctor of Philosophy – Degree Certificate

References

| https://mg.co.za/article/2016-05-17-black-graduate-numbers-are-up [15] | |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A note on source data: Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. |

| http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20140905134914811 [27] | |

| http://www.education.gov.za/ [42] | |

| http://www.cde.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/LOW-FEE-PRIVATE-SCHOOLS.pdf [44] | |

| ↑6 | Spaull, Nic: Schooling in South Africa: How low-quality education becomes a poverty trap, http://ci.org.za/depts/ci/pubs/pdf/general/gauge2015/Child_Gauge_2015-Schooling.pdf, 35 Accessed March 2016. |

| ↑7 | Spaull, Nic. “For-profit schooling in SA: An overview and discussion for the IEB.” September 2, 2015. Retrieved from https://nicspaull.com/presentations/ |

| ↑8 | Department of Higher Education, Strategic Plan for Fiscal Years, 2015/16- 2019/20, p. 16. |

| ↑9 | In 2008, the NSC replaced the Senior Certificate as the final school-leaving certificate. |

| http://www.UMALUSI.org.za/docs/research/2013/nsc_pass.pdf [55], accessed April 2017. | |

| http://www.UMALUSI.org.za/show.php?id=2894 [57]. | |

| ↑12 | Spaull, Nic: Schooling in South Africa: How low-quality education becomes a poverty trap, http://ci.org.za/depts/ci/pubs/pdf/general/gauge2015/Child_Gauge_2015-Schooling.pdf, Accessd March 2016. |

| ↑13 | Ibid., 36. |

| http://www.saqa.org.za/list.php?e=NQF [63]. | |

| University of Stellenbosch [64], notional learning hours are “the estimated learning time taken by the ‘average’ student to achieve the specified learning outcomes of the course-unit or programme. They are therefore not a precise measure but provide students with an indication of the amount of study and degree of commitment expected. Notional learning time includes teaching contact time (lectures, seminars, tutorials, laboratory practicals, workshops, fieldwork etc.), time spent on preparing and carrying out formative and summative assessments (written coursework, oral presentations, exams etc.) and time spent on private study, whether in term-time or the vacations.” | |

| http://www.dhet.gov.za/ [67] – Pages 8-9 | |

| ↑17 | Levy, Daniel C.:South Africa and the ForProfit/Public Institutional Interface, https://ejournals.bc.edu/ojs/index.php/ihe/article/download/7011/6228, Accessed March 2017. |