Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Between 2015 and 2016, the European Union experienced an unprecedented influx of refugees commonly described as the “European refugee crisis”. More than 1.3 million refugees crossed the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas trying to reach Europe, as per the refugee agency of the United Nations, UNHCR [2]. Thousands of refugees lost their lives, drowning on the treacherous sea passages. Germany has been a magnet for those who make it, absorbing more refugees than any other country in the EU. In 2015, the country famously adopted an “open border [3]” policy. That year, it took in 890,000 refugees and received 476,649 formal applications for political asylum – the highest annual number of applications in the history of the Federal Republic.

By 2016, the government had moved to a far less welcoming stance and reinstated border controls. An agreement between the EU and Turkey, signed in March 2016, allowed Greece to return “irregular migrants [4]” to Turkey and has made it more difficult for refugees from the Middle East to reach Western Europe overland. As a consequence, the total number of refugees arriving in Germany in 2016 dropped sharply to 280,000 [5]. Still, the country continues to take in most of the refugees in the EU, and its efforts to integrate those newcomers are instructive to anyone interested in what it takes to integrate substantial populations of refugees, often with varying levels of skills and qualifications, into the workforce and institutions of higher education.

This article looks at the nature and impact of Germany’s integration efforts, especially vis-a-vis higher education and the workforce. It examines both the challenges and the benefits, particularly in the long term. The German experiences, we believe, may be relevant for countries like Canada [6], which in 2015 committed itself to an annual goal of admitting at least 25,000 Syrian refugees.

The upshot is that, Germany’s extensive support for refugees is both a remarkable humanitarian gesture, and an example of economic pragmatism. Complex, costly, and controversial up front, integration efforts have already had some positive short term economic impact. More importantly, they may emerge as part of a much-needed solution to the long term economic challenges posed by a rapidly aging native population.

[7]

[7]Hegyeshalom, Hungary – October 6, 2015: Group of refugees leaving Hungary on their way to Germany.

Refugees in Germany: The 2015-2016 Spike

The tremendous flow of displaced persons into Germany happened despite the fact that the country is geographically and legally well-shielded from overland refugee migrations. EU treaties stipulate that asylum seekers can only apply for asylum in the first EU country that they enter, and that they risk deportation should they try to apply in another state. But the German government in 2015 refrained from deporting refugees from Syria, and opted to process asylum applications from refugees that arrived via so-called “safe third countries [8].”

Germany’s desirability as a destination for asylum seekers is long standing: Over the past 30 years [9] it received a reported 30 percent of all asylum applications in Europe – a greater share than any other country. Aside from the perception of Germany as a safe and prosperous country with liberal asylum laws, the strong diaspora networks [10] that have built up over time, particularly with Middle Eastern countries, act as a pull for new arrivals. Refugees and migrants arrive from a variety of places, spurred by civil wars, economic crises and the breakdown of political order, for example, in African countries like Somalia, Libya, Sudan, Eritrea or Nigeria. The 2015 spike, however, was driven primarily by the civil wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and, most notably, the savage conflict in Syria, the main country of origin in the recent crisis.

Overall, the influx of the refugees in Germany has resulted in the biggest population increase in more than 20 years [11] and has boosted Germany’s population by more than one percent. The boom has been driven in large part by the arrival of young men, especially those with disposable funds to pay for human traffickers. The dangers of the passage to Europe give an advantage to young males, while deterring many women in what has been described as “asylum Darwinism [12].” Fully 65 percent of all asylum seekers in Germany between 2015 and 2017 were male; more than 50 percent were below the age of 24 [13], and about a quarter of all refugees were children below the age of 15. Family members who follow new arrivals have further increased the number of migrants entering Germany. In 2015, 82.440 refugee family members [14] arrived in Germany, mostly wives following their husbands.

Managing the Influx, Priority 1: Workforce Integration

Incorporating refugees into Germany’s workforce is vital to mitigating the social and economic impact of the crisis. High economic costs and the specter of “parallel societies [15]” that arose in neighboring countries like France helped prompt Germany’s government to devote tremendous resources towards the economic and social integration of the refugees. A snapshot from March 2017 gives a sense of the scope of the investment: during that month alone, some 465.000 refugees [16] sought some form of assistance from German job centers and public employment agencies – the majority of them still enrolled in vocational training and integration courses (discussed below).

The extent to which refugees are allowed to work in Germany depends on their particular immigration status.http://www.bamf.de/DE/Infothek/FragenAntworten/ZugangArbeitFluechtlinge/zugang-arbeit-fluechtlinge-node.html [17] Refugees that have been granted political asylum, however, are generally entitled to seek employment without restrictions. Despite this formal access to employment, labor market integration of refugees remains challenging. The percentage of employed persons among refugees is small, and most refugees that are presently working arrived prior to the big wave of 2015/16.

The backdrop to this employment issue is notable: The integration of immigrant populations in Germany is problematic in general, due to language barriers, resentments in German society, and other factors. Compared to German natives, for instance, immigrants are less successful in school, less likely to be employed [18], and earn far less when they do find work. The workforce integration of the refugees thus needs to be understood as a long-term process that is likely to accelerate over time. While only an estimated nine percent [19] of refugees who arrived in 2015 were employed by 2016, that same figure was 22 percent among refugees that had arrived in 2014, and 31 percent among those that had arrived in 2013.

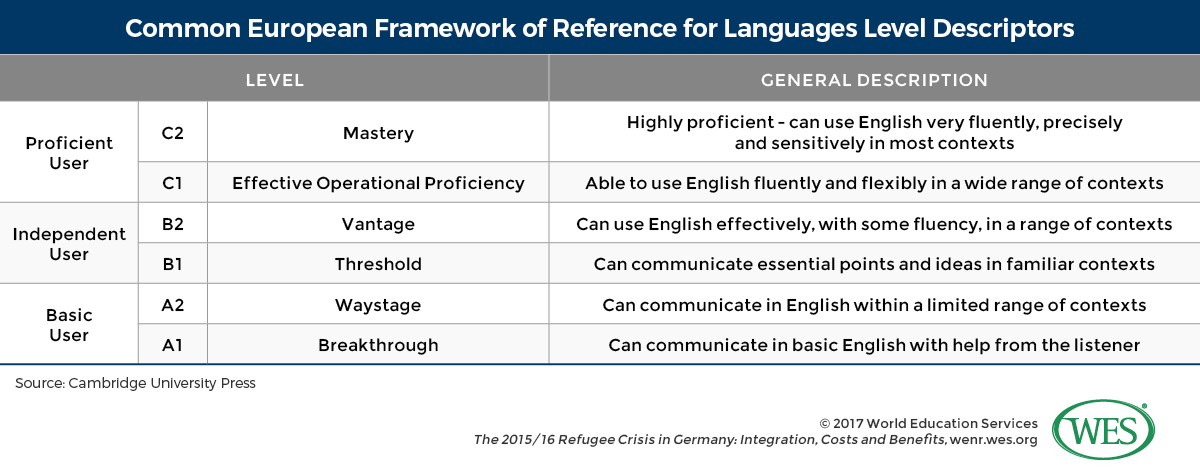

One focal point of German government efforts to accelerate employment among refugees has been a 9-month integration ‘course’. Established in 2005, long before the current crisis, the course is designed to expedite the assimilation of approved asylees, helping them to obtain needed linguistic skills, as well as softer cultural skills and understanding. The course includes a 60-hour cultural “orientation” unit introducing German society and culture, as well as 600 contact hours of German-language instruction. One goal is to enable participants to obtain an intermediate-level language certificate at level B1 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages [20] (CEFR). In the wake of the 2015 crisis, asylum applicants, and other ‘tolerated’ refugees were granted permission to take these courses prior to obtaining asylee status. In July 2016, Germany’s government passed legislation requiring that asylum seekers take integration courses [21], lest they lose government benefits and the legal right to remain in the country.

Other government initiatives have focused more directly on job placement. In 2016, the federal government, for example, funded [23] 100,000 seats in job-related language training courses for refugees. The goal is to help trainees improve their language skills in order to graduate from vocational training programs, or gain subject-specific language knowledge. The language skills required for these programs go beyond the standard integration courses – applicants must demonstrate language skills at B1 CEFR level in order to be admitted.http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bundesrecht/deuf_v/gesamt.pdf [24] Another ambitious government project sought to subsidize up to 100,000 so-called “One Euro Jobs” for refugees at the cost of 300 million Euros [25] annually. One-Euro jobs provide employers with cheap, government-subsidized labor, while at the same time allowing refugees to gain practical experience, improve language skills and cultivate contacts that may lead to regular fulltime employment.

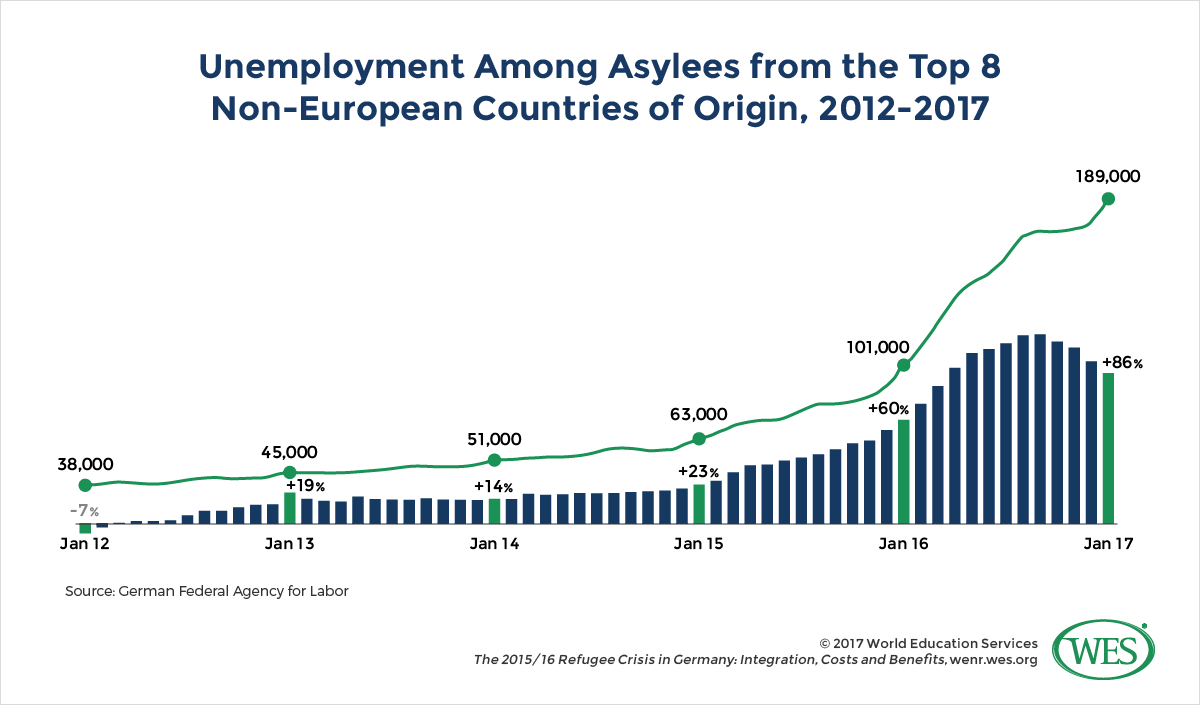

To date, workplace integration efforts have had limited impact. In January 2017, 129.000 refugees from the top eight sending countries [16] were officially employed in Germany – a substantial 45 percent increase in volume over the year before. However, 189,000 remained formally unemployed, an 86 percent volume increase over the year before.

The reasons behind the sluggish progress are multiple. Integration courses, for instance, can be overcrowded, and the teachers are often underpaid and underqualified [26]. Many students complete the course without significant German-language skills. Pass rates for the B1 CEFR language certificate are reportedly below 60 percent [27] (2013), and students who are successful tend to be those who arrive with better educations in the first place.

In most German states, B1 CEFR certification is required [28] for work in regulated fields like nursing and allied health, while the advanced C1 level certificate is required for regulated professions like teaching, for example. Low pass rates have an impact on asylee employability. According to the OECD, refugees with language skills at level B1 are employed in significantly larger numbers [29] in Germany compared to those without.

The impact of the One Euro program has also been disappointing. Critics charge that it “parks” refugees in low-skilled, low-income jobs without leading to integration. It has so far also had limited reach: As of November of 2016, only 4,392 refugees (out of the desired 100,000) [30] were reported to be employed in “One Euro Jobs.”

In addition to government programs, there are numerous private sector initiatives in Germany to help refugees into the workforce. Like the public sector programs, these private initiatives have not yet done much to boost refugee employment. One problem with the current private initiatives is that they often focus on low-skilled jobs, internships and temporary positions that, as of now, rarely lead to fulltime employment. For instance, some 300 companies included in a so-called “Network of Businesses Integrating Refugees [32]” employed a total of 2,500 refugees [33] in October 2016. This figure, however, also included temporary employment contracts, internships, and training programs. German businesses tend to be careful when hiring refugees and often use internships to evaluate the suitability of refugees for subsequent vocational training programs. This means that refugees on this track are often still years away from actual fulltime wage jobs.

Managing the Influx, Priority 2: Education

During the chaotic first year of the current refugee crisis, it was difficult to obtain reliable demographic information on new arrivals. Once the situation stabilized and first data had been collected, it became clear that language skills and lack of educational attainment were among the chief barriers to workforce integration. In light of these barriers, access to higher education is important for the long-term social advancement of sizeable numbers of refugees, especially since more than half of the current asylum seekers are below the age of 25.

Among the many efforts to facilitate refugee access to higher education, one of the most groundbreaking is provided by Kiron University [34], a non-profit, crowd-funded online university that was founded in 2015 with the exclusive goal of educating refugees. The institution partners with online education platforms like coursera [35] or edx [36] to provide free online courses, using existing online course offerings by world-class universities including Harvard University, the University of Cambridge, or MIT. The service offered by Kiron University is remarkable: Not only does the institution not have academic admission requirements, language, passport and residency requirements, or, for that matter, any other forms of bureaucratic hurdles; it even provides each student with a free laptop and internet access.

Kiron is not a recognized university in Germany and does not award degrees. But 22 partner universities [37] in Germany and other countries currently allow Kiron students to transfer into their degree programs, usually after completion of four semesters of study at Kiron University. The large number of donations and applications that Kiron has received since its foundation are testament to the fact that many refugees are seeking a less bureaucratic and more immediate alternative to the comparatively hurdled long-term pathways available at German brick-and-mortar universities. In its first semester alone, Kiron received 5,000 applications, 80 percent of them from Syrian refugees. [38] The institution currently enrolls 2,300 refugees.

This, of course, is a drop in the bucket compared to the estimated 50,000 refugees [39] who are reportedly interested in pursuing a degree in Germany. And the number who have successfully registered in degree programs at regular universities is even smaller. In the 2016 winter semester, a total of 1,140 refugees [40] were matriculated at German universities, the majority of whom were from Syria.

Asylees can generally attend German universities without restrictions. The lack of German language proficiency and other hurdles, however, deter refugee enrollment at public universities. At the undergraduate level, where degree programs are almost exclusively offered in German, all international students, including refugees, must present a qualification equivalent to the German university-preparatory high school diploma, and demonstrate advanced German language abilities, at minimum at level C1, CEFR. For English-language programs, which exist primarily at the graduate level, a comparable certification of English skills, such as the TOEFL test, may be required.

A number of universities also require foreign students to sit for a centralized admission test called “TestAS [41]”. This aptitude test, which is now free for refugees and increasingly offered in Arabic, can, on occasion, enable institutions to place refugees who lack academic documents.

Most universities, however, require students without documentation or adequate credentials to enroll in German-language academic foundation courses. The federal government is presently funding an additional 2,400 seats in foundation courses annually, creating a total of 10,000 seats until 2019 in a program called “Integra.” These courses, which are distinct from the general integration courses discussed above, usually last two semesters, and include 28 to 32 hours of instruction per week. Coursework is capped by a final examination, the “Feststellungsprüfung [42],” which provides students who pass with access to German universities.

A number of German universities allow refugees, even those whose legal status is still in limbo, to attend university lectures and register for audited non-degree courses [43] outside of the standard admission procedures.

Beginning in 2015, the federal government launched a promotional campaign and increased academic advising for refugees as part of an effort to increase enrollments. It further expanded the number of language courses and seats available to refugees in academic prep courses. The €100 million [44] four-year initiative is funded until 2019.

Recent reforms [45] have also greatly improved asylees’ access to financial aid. Until recently, asylees had to wait four years before they were eligible for government student loans in accordance with the Federal Education Assistance Act (“BAföG”). Since 2016, asylees and “tolerated refugees” can apply for these monthly loans of up to 720 Euros after only 15 months in Germany. That said, access to financial aid is contingent on enrollment at a recognized university, and the vast majority of refugees do presently not have the necessary language skills to gain access to degree programs.

The fact that most refugees have to first complete language training and foundation courses means that many of them are still years away from matriculating at a German university. At the University of Hamburg, for example, only 30 refugees [46] applied for regular study programs in the winter semester of 2016, even though hundreds of them were enrolled in the university’s prep courses.

Current problems notwithstanding, the number of refugees participating in German higher education can be expected to increase considerably in the coming years. Between the 2016 summer semester and the 2016 winter semester, the number of refugees registered for foundation courses reportedly increased by 80 percent [40] to 5,700 refugees. Almost 70 percent of these refugees are seeking enrollment in a bachelor’s program, while about 20 percent intend to study at the master’s level.

Short-Term Costs, Long Term Benefits

The refugee crisis has given rise to an increasingly polarized political debate in Germany that often tends to focus on negative aspects, such as costs, social problems and security concerns, while underemphasizing the potential long-term benefits the influx of the refugees could generate for German society.

The high immediate public sector costs have helped to inflame the debate. Social welfare payments for asylum seekers alone amounted to 5.3 billion Euros [47] (US $5.76 billion) in 2015 – an increase of 169 percent over 2014. In 2016, the government spent 21.7 billion Euros [48] on refugee-related expenditures. Among the 2016 expenditures [49] were 5.3 billion Euros for integration measures and 4.4 billion Euros in social welfare payments for asylees and tolerated refugees.

In 2017, Germany’s government allocated 21.3 billion Euros [48] to refugee assistance, a slight decrease from 2016 spending, but more than six percent of its 2017 annual operating budget of 329 billion Euros [50]. That amount, which includes preventive measures like humanitarian aid in crisis countries, as well as financial aid to countries like Turkey and Greece, represents more than half of the country’s current annual defense budget of 37 billion Euros.

While these costs may look staggering, it should be noted that the federal government ran a budget surplus of 6.2 billion Euros [51] in 2016. Moreover, it’s arguable that the crisis has had a number of benefits for the German economy. As the German economist Ferdinand Fichtner has noted, the refugee expenditures function in some ways as one “big economic stimulus package [48],” injecting billions of Euros into the economy. The crisis has also provided “windfall profits” in the private sector, often in the form of surging government demand for items ranging from services to food and housing. In the housing sector for instance, the effect on demand has been considerable: 800 million Euros were allocated in 2017 in just one German state alone to subsidize the construction of new social housing units [52], primarily to accommodate refugees. One notorious example involved manufacturers of housing containers, which are often used as refugee shelters. These companies reportedly profited [53] by increasing prices in the face of growing demand.

Current public sector costs also have to be weighed against looming demographic pressures on Germany’s traditionally strong economy. Some 28 percent of Germans are aged 60 years or over [54], and in 2015, Germany had the world’s second oldest population after Japan. The German government recently calculated [55] that the population would decline from 82.1 million to somewhere between 67.6 and 78.6 million by 2060 – a trend that would exacerbate Germany’s already existing shortage of skilled labor.

In response to that shortfall, Germany is now seeking to stimulate immigration, testing [56], for example, a points-based immigration system for skilled workers modeled after Canada’s immigration system. Against this backdrop, the influx of a population of young, eager-to-work refugees could easily be seen as a boon.

At present, refugees generally lack the language skills and vocational qualifications required by the highly formalized German labor market. In the long term, the situation may improve, especially since labor shortages are most acute [57] for medium-skilled workers. A 2016 study [58] by the research department of Deutsche Bank concluded that the successful integration of the refugees could help to balance Germany’s age structure and increase its labor force, and should be regarded as an “investment in the future” and “win-win scenario” with the potential to give Germany “the opportunity to consolidate its position as Europe’s economic powerhouse.”

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has made a similar assessment of the potential benefits offered by this influx of refugees in a 2016 report [59] on the German economy. The report noted that, in the face of a “projected decline in the labor force due to aging after 2020 … additional policies to integrate the current wave of refugees into the labor market… would not only counter the … decline in the medium term but also stimulate private consumption and investment.”

The IMF’s 2016 assessment called for further policy actions “to promote a successful labor market integration of refugees,” and enhanced “measures to allow recognition of informally acquired skills and facilitate more flexible forms of vocational training, with a strong on-the-job component and intensive language teaching.”

Much of these projected benefits will depend on the speed and success of integration efforts, and more work is needed. The stakes are high: If integration fails, the continued presence of large numbers of refugees in Germany could result in sustained net transfer payments from the public sector, while at best providing a supply of labor for low-skilled jobs.

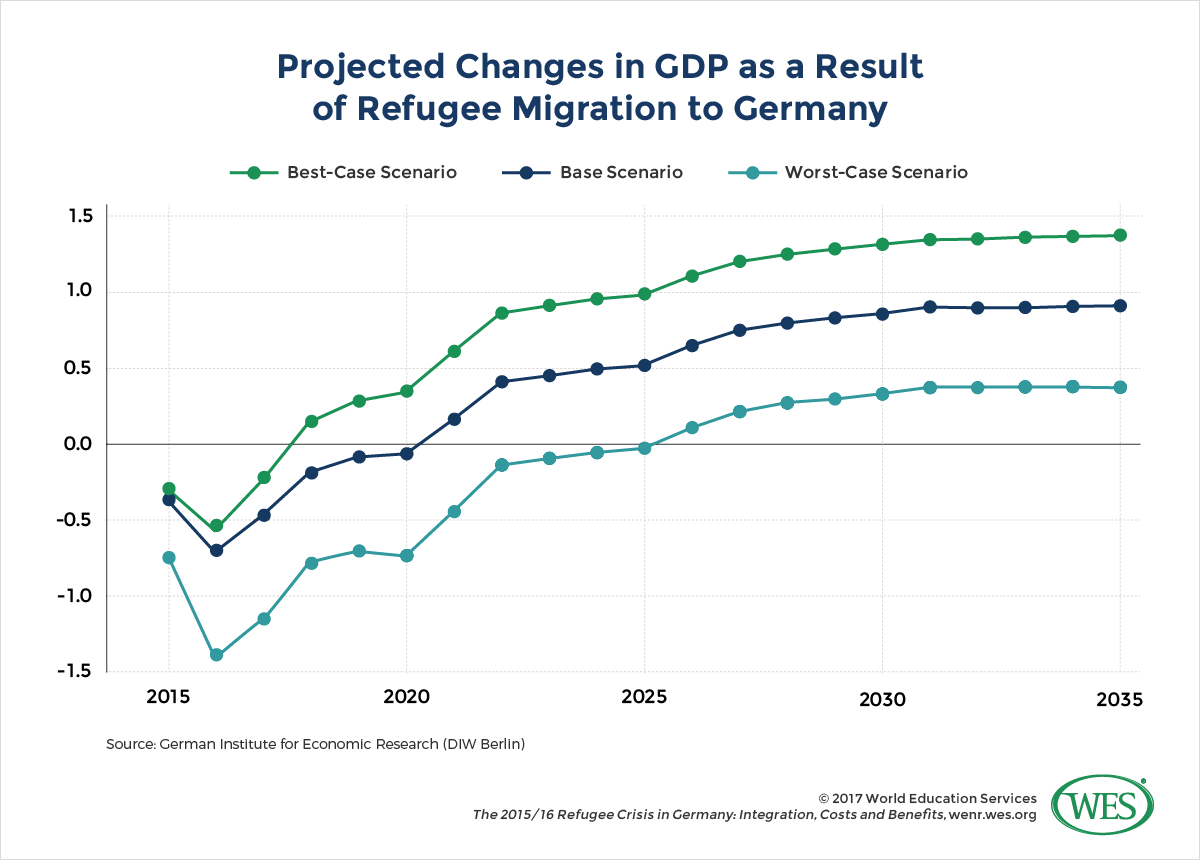

But if the integration succeeds, the economic benefits promise to be considerable. A 2015 study [60] by the “German Institute for Economic Research” predicted that the current cost-intensive investments in integration would, within the next years, reach a break-even point. After that, increased employment and consumption by the refugees may stimulate economic growth that could, in the best case-scenario, yield more than a one percent increase in German GDP by 2025.

Baseline Challenges to Integration

In 2016, Joachim Möller, director of the Research Institute of Germany’s Federal Labor Agency, described [61] a best case scenario in which 50 percent of the current refugee population was employed within the next five years – a prediction, he added, that would be contingent upon increased efforts at integration. Past experience shows that refugee labor participation is bound to grow over time, but success demands addressing a number of baseline challenges:

Educational Attainment

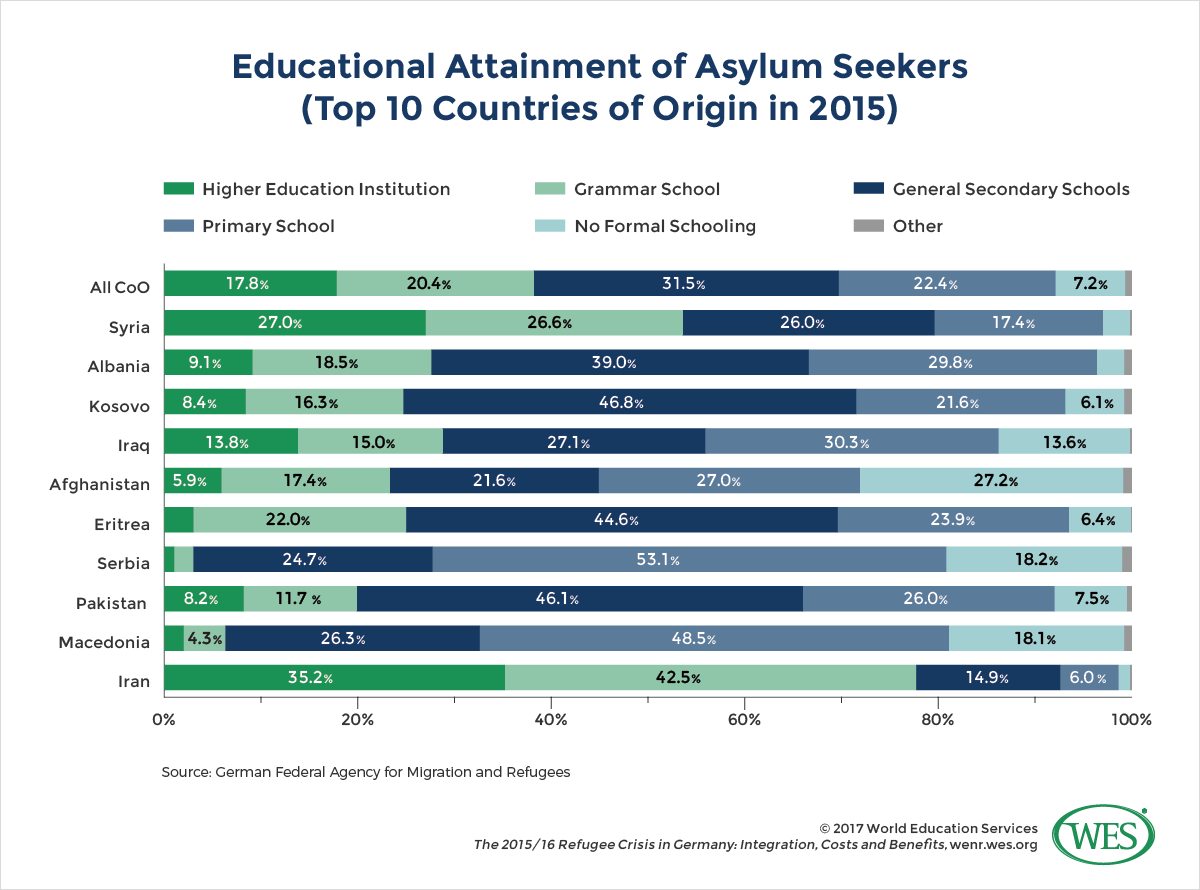

The level of educational attainment among the current refugees is diverse and tied to country of origin, but generally falls below German attainment levels. According to estimates [62] by the German Agency for Labor from early 2016, less than half of the current refugees from Afghanistan, for instance, had more than elementary education, 27 percent did not have any form of formal schooling at all. The reason for these low attainment levels is simple: The education system in Afghanistan has been paralyzed by war for decades. Refugees from Syria are, by comparison, much better educated. More than 50 percent of Syrian refugees had at least secondary schooling, and 27 percent had some form of tertiary education, if not necessarily a degree.

In general, about one fifth of all current refugees from the top sending countries are estimated to have attended a higher education institution, and approximately two thirds have attended secondary school. A representative survey of 2,300 refugees [19] from all countries of origin, conducted in June of 2016, largely confirmed these estimates: 19 percent of respondents attended higher education institutions in their home countries; 13 percent had a university degree.

While these attainment levels are short of European standards, they often outstrip education levels in refugees’ home countries. The fact that the passage to Europe is costly means that privileged and educated segments of society tend to be overrepresented among the refugees, while less wealthy people have little means of escape. In the case of Syria, for example, the high percentage of secondary school graduates among the refugees compares to an upper-secondary gross enrollment ratio of just 41.5 percent in Syria itself (in 2011, at the onset of the war, as reported by the UNESCO Institute of Statistics [63]). At the higher education level, only 15 to 20 percent of the 2011 age cohort [64] in Syria was reportedly enrolled in a higher education program.

Prior Work Experience

An estimated 35 percent [62] of refugees who arrived in Germany from the top sending countries in 2015 did not have work experience prior to fleeing their countries. This widespread lack is, in context, perhaps unsurprising. Given the average age of the refugee population in Germany, many new arrivals may never have had the chance to find or hold a job. Low labor participation among women in top sending countries such as Afghanistan, Pakistan and Syria may also be a factor.

By comparison, a 2016 survey of working-age refugees [19] from all countries of origin indicated slightly greater experience: 73 percent of the 18 to 65-year old respondents had prior work experience – 81 percent of men and 50 percent of women. However, some 69 percent of respondents to the 2016 survey lacked both formal vocational training and the type of professional qualifications usually required on the German labor market. In other words, the work experience many refugees bring to their new country has little relevance to the German job market. Some 27 percent of refugees were self-employed; 30 percent worked in blue collar jobs. Refugees from other top sending countries, Eritrea, for example, arrive with military experience that does not readily transfer to the German labor market.

Other refugees arrive as skilled professionals with university degrees. Among these arrivals, employment has been concentrated in teaching professions, medical fields, and engineering. Refugees from Syria, in particular, included a disproportionally high percentage of medical doctors and dentists – coveted professions in pre-war Syria, where the ratio of doctors to population used to be among the highest in the world [64]. In Germany, the high percentage of Syrian doctors is reflected by the fact that Syrians represent the fourth largest group among foreign doctors in the country – 2,159 Syrian doctors [64] are said to presently practice in Germany.

As in most countries, licensure requirements for professional vocations in Germany are relatively inflexible A robust qualifications recognition process is thus vital for skilled refugees seeking placement on the German job market.

A formal evaluation and recognition procedure [66] for foreign qualifications has been in place in Germany since 2012. The process, established to ease the movement of skilled workers within the EU, is open to all foreigners, including refugees. In 2015, the federal government allocated 2.2 million Euros to promote the program among refugee populations. Information on qualification recognition is now provided via mobile application in Arabic, Dari, Farsi, Tigrinya und Pashto – the languages most commonly spoken by refugees.

Among the benefits this recognition procedure offers refugees is a provision that allows persons who cannot submit supporting documents for evaluation to undergo a “skills analysis” – a process which typically involves the submission of work samples, interviews or practical examinations. If foreign credentials are found incomparable to German qualifications, further education programs may also be offered to convey missing skills in the framework of a program called “integration by qualification [67].”

Since many refugees arrive in Germany without documents or evidence of professional qualifications, the practical “skills assessment” can help many qualified refugees who do not possess supporting documents. At the same time, the process has short-comings. The majority of recognition applications between 2012 and 2015 [68] were concentrated in the fields of teaching, engineering, nursing, and medicine. Since most refugees obtained much more informal training in foreign education systems that are vastly different from the hyper-regulated German system, a more general “competency assessment” that is less focused on formal qualifications may be needed to ensure quicker integration of a far greater number of refugees. Critics contend that the current process is presently too formalized,https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301787839 [69]. Accessed March 2017. since it does not meet the needs of a young refugee population that, for the most part, lacks formal employment qualifications.

Language Barriers

Almost half of the refugees who reached Germany in 2015 spoke Arabic as their native language. While 28 percent of surveyed first-time asylum applicants said that they spoke English, a mere two percent stated that they knew any German. Among refugees from the main countries of origin, German language skills were even lower [62]: Only 1.1 percent of Syrians, 0.6 percent of Afghanis, and 0.4 percent of Iraqis spoke German. In other words, German language skills are virtually nonexistent among recent arrivals.

Language barriers constitute one of the main obstacles to integration not only in Germany, but also in English-speaking countries like the UK [70] and Ireland [71]. One particular challenge of the current situation in Germany is the large number of school-aged children among the recent refugees. An estimated 325.000 children between the ages of 6 and 18 have arrived in Germany in 2014 and 2015 alone. Estimates by the governments of the 16 German states in 2015 suggested that effective schooling of the refugee children – including special language classes or core classes taught in languages other than German – would require the recruitment of 20,000 additional teachers at a cost of €2.3 billion annually [72]. While this estimate was later cut by as much as half, it represents an enormous gap that will be difficult to fill since there is a shortage of available teachers [73] on the German labor market.

If children now in elementary and secondary schools manage to learn German sufficiently well, many of them will likely not face the same integration hurdles and access challenges that adult refugees are currently experiencing on the German labor market. One 2016 survey [74] of management staff from 354 companies suggested that a majority of German companies, while generally amicable to hiring refugees, are reluctant to employ refugees in full-time or higher level positions. More than 70 percent of respondents were willing to place refugees in internships and temporary positions, but only 35 percent were open to hiring refugees for full-time jobs. Just a minority were open to placing refugees in leadership or higher administrative positions (21 and 23 percent, respectively). The biggest hurdles for employment cited by the managers were language barriers and missing vocational skills. Another factor at play may be discrimination against applicants from different cultural, particularly Muslim, backgrounds [75]. Some 36 percent of respondents listed cultural differences as a reason for not employing refugees.

Going Forward

When the refugees arrived in Germany they were greeted by an outpouring of sympathy by many German people. The crisis was accompanied by increases in donations, civic engagement and volunteer initiatives, ranging from free German lessons to the sheltering of refugees. At the same time, the government’s open door policy was not favored by all Germans, and the crisis coincided with an almost immediate and significant drop in popularity ratings [76] of German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Two years after the onset of the crisis, attitudes towards refugees have turned increasingly negative and the government’s refugee policy has become harder to defend. Key turning points in public opinion included news of mass sexual assaults [77] committed by newly arrived foreign nationals on New Year’s Eve 2015, and a string of ISIS-inspired terrorist attacks in 2016, most of them perpetrated by asylum seekers. In January of 2017, 42 percent [78] of surveyed Germans considered refugees a threat to German culture, up from 33 percent in October 2016; 56 percent of respondents disapproved of Chancellor Merkel’s handling of the refugee crisis, up from 49 percent; 70 percent believed that growing numbers of refugees would result in increased crime rates, up from 62 percent.

More expansive support for the intake of refugees, thus looks unlikely in Germany’s near future — as it does across Europe at large. Anti-European and anti-immigrant movements have been quick to exploit rising fears for political gain. This dynamic is clear in the increased popularity of nationalist parties, such as France’s “Front National” or the Dutch “Party for Freedom” (PVV). The successful Brexit campaign in Great Britain last spring demonstrated the potency of immigration as a topic for political mobilization when weighed against more abstract arguments for long-term economic benefits.

In Germany, the refugee crisis has contributed to changes in the party system and given rise to the nationalist right-wing party, “Alternative for Germany” (AFD). Originally founded in 2013 on an anti-European platform, the AFD has gained popularity primarily on the back of the refugee crisis [79]. The party, which is now represented in the parliaments of eleven out of 16 German states, calls [80] for radical cutbacks in immigration and openly campaigns against the presence of Muslims in Germany. In 2016, the AFD achieved double digit results in three state ballots and became the second-largest party in the East German state of Saxony-Anhalt with more than one fifth of the vote, even though it contested in these ballots for the very first time.

In this sense, the political effects of the recent crisis outweigh its economic impact. The current popular backlash against asylum policies in Europe is intertwined with anti-EU positions. Conflicts between member states over asylum laws and quota systems for the distribution of refugees have decreased solidarity, and further polarized a European Union already strained by events like the sovereign debt crisis. Right-wing parties across the continent now seek to reclaim national sovereignty in order to independently regulate matters such as asylum policies. The rising strength of these parties has turned national elections in many European countries into nail biters for the pro-European political establishment, and made it increasingly difficult to ignore calls for popular referendums on EU membership.

Germany’s own September of 2017 national elections are likely to be a referendum on Germany’s refugee policy, and related concerns. Most German mainstream parties, including Merkel’s own Christian Democratic Party (CDU), have so far proven resilient to pressures to radically change the country’s asylum policies. However, the nationalistic, anti-immigrant AFD party is not only expected to reach the five percent threshold to make it into the national parliament, but could become Germany’s third largest party with approximately nine percent of the vote, according to almost all current forecasts [81].

This political backlash has recently caused the German government to propose increases in deportations [82] and to call for the establishment of European asylum processing centers in North Africa in order to contain migration flows [83]. Merkel has vowed that the situation of 2015 “cannot repeat itself [84],” and that migration will be handled in a more controlled manner. While it is unlikely that Germany will close its doors to refugees anytime soon, the open-door policy of 2015 was a historical exception that has given way to a more cautionary approach.

References