Megha Roy, Senior Research Associate, WES

The U.S. consistently attracts more international students than any country in the world, enrolling an all-time high of over a million international students nationwide during the 2015/16 academic year [2]. However, student recruitment is taking place in an increasingly competitive global education landscape. Countries like Australia and Canada have established themselves as attractive higher education destinations for students from key markets. In response, U.S. institutions have begun to use more aggressive recruitment practices. The use of education agents, already well established among Australian, British, and Canadian universities [3], is one such practice.

Agent use in the U.S. has risen rapidly in a very short time. Until 2013, the National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC) held that the use of university-commissioned international recruitment agents was unethical – a position aligned to a federal legal ban on the domestic use of such agents. After intense debate, NACAC revised its ethical standards [4] to permit institutions to commission recruitment agents abroad. The 2013 revision radically changed the landscape of international recruitment in the U.S. According to the a widely cited 2016 report by the Bridge Education Group [5], nearly half of U.S. institutions reported that they directly or indirectly used international agents, including the 12 percent that engage with pathway programs, and 37 percent of surveyed institutions, that had actually commissioned agents to work on their behalf. The survey found that another 30 to 40 percent were considering using such agents.

Despite this rapid embrace of international education agents, the agent debate is ongoing and heated. It flared again as [6] recently as March, when the Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE) proposed a policy prohibiting the institutions it accredits from providing financial compensation to international education agents.

To date, much of the discussion about agent use has focused on transparency, accountability, and integrity. With an eye toward these concerns, professional organizations such as NACAC [7], American International Recruitment Council (AIRC [8]), and NAFSA [9] have all laid out guidelines and best- practices for working with commission-based agents.

What’s largely missing from the conversations, however, are:

- Research-based insight into students’ own experiences with agents, whether commission based or independent

- An understanding of how students’ use in different regions independent vs. sponsored or commissioned agents

- Significant insight into the experiences of students outside of Asia

A NOTE ON OUR ANALYSIS

Survey results are broken down by region of origin. We compare results for students from the top two sub-regions of origin – South and Central Asia, and East Asia – as well as from several major world regions: Sub-Saharan Africa, Europe, and Latin America and the Caribbean. *

The survey examines services used at different points in the enrollment funnel – discovery, application, and enrollment. It also provides insights into the different types of education agents used by international students in different parts of the world. These include institution-sponsored agents – those who receive commissions from or have a contract or agreement with U.S. institutions; and independent educational agents – those who are paid by the students and their families.

* Response rates from Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa were very low, thus findings are not discussed with one or two exceptions.

The Agent Landscape Through Applicant Eyes

“My agent helped me get into every school I applied to.” – Graduate student, Peru

“They had insufficient knowledge of the degree program, or the characteristics looked for by different schools.” – Graduate student, Hong Kong

In March 2017, the research team at World Education Services (WES) surveyed 5,880 international students representing five regions and over 50 countries. Our goal was to better understand their experiences with education agents. All survey recipients came from a pool of former WES applicants for foreign credential evaluation. Some were currently enrolled in U.S. higher education institutions; others were still planning to enroll.

Our research sought to uncover:

- The prevalence of agent-use among WES applicants

- The types of agents used (e.g., independent educational agents, who are paid by the students/families, versus institution-sponsored agents, who receive commissions from the U.S. institutions)[1]The definition of education agent was provided to the respondents as “an individual, company or organization that provides educational advice, support or placement to students in a local market who are interested in studying abroad.” Also, for the sake of simplicity, the terms “agency,” “agent,” “international student recruitment agency,’” “education agency” or any third party “education advisor” and “education consultants” were referred to as “AGENT.”

- How applicants interact with agents – how they pay them, what services they use when, their satisfaction levels, challenges, and more

- Regional variations in agent use and type

The intent behind this work was not to inflame an ongoing debate about ethics, but rather to deepen institutions’ insight into some of the complexities of the global agent market as experienced by students. We also sought to shed light on markets where little research has been conducted. To date, most of the relevant research has focused primarily on the use of agents in Asia; trends in other markets have not been highlighted as often. [2]There are some exceptions to this rule. One 2014 study, for instance, examines the use of agents from U.K. institutions to recruit students from Sub-Saharan Africa. (Moira Hulme, Alex Thomson, Rob Hulme and Guy Doughty (2014) Trading places: The role of agents in international student recruitment from Africa, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 38:5, 674-689, DOI: 10.1080/0309877X.2013.778965)

We believe that insights into student views and unexplored markets can help to inform institutions that already have relationships with agents. We also believe that both those institutions and those that do not, for whatever reason, work with agents need to understand the broader market — especially given the prevalent use of independent agents by a significant proportion of international applicants from around the world. Such agents have an invisible but powerful role in the admissions process for almost one in four international students.[3]NOTE: This survey was self-reported and was incentivized with prize drawings of five USD $50 Amazon gift cards, which may have induced bias in responses. The definition of agent or definition about their business operations/type might not be clear to some respondents. For the simplicity of the survey, an agent’s definition was generalized for students as many students may not be able to distinguish between different types of agents and hence the survey does not bring out differences between agents/counsellors/advisors from an institutional perspective. Since the survey went out to WES credential evaluation applicants, there could be a higher representation from certain students that have both a higher awareness and usage of WES services.

A Snapshot of Key Findings

Our research found that about 23 percent (1,336 students) of respondents used agents during the application process. Of those:

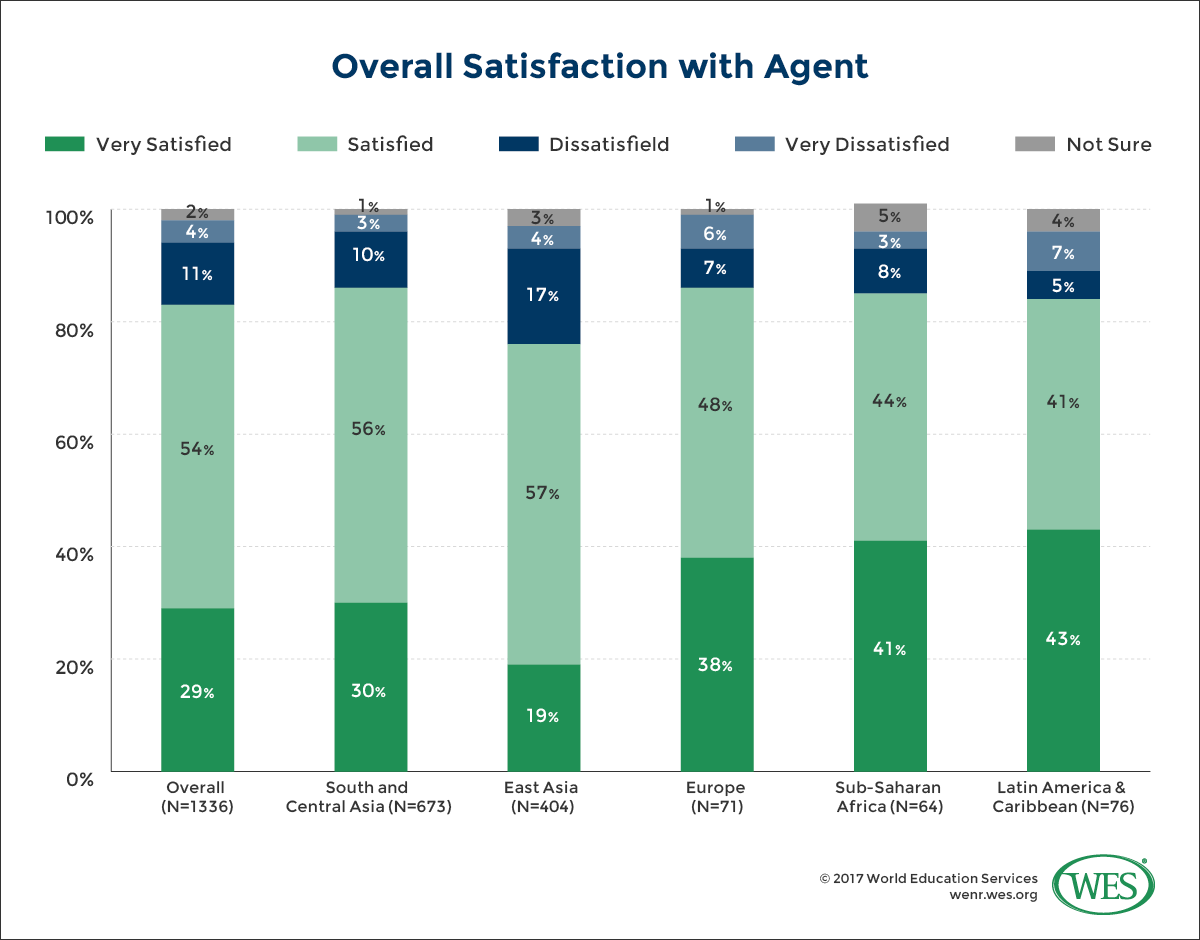

- Eighty-three percent were satisfied with the services offered, and indicated that agents met their expectations. More than 75 percent agreed that agents provided useful information and valuable suggestions; more than 70 percent indicated that the expenses were reasonable.

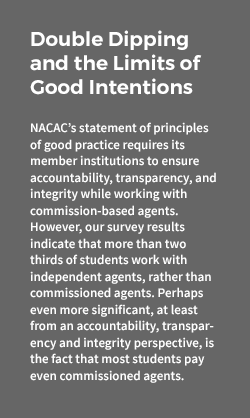

- Two thirds used independent education agents rather than institution- sponsored agents.

- Two-thirds of students who use institution-sponsored agents paid them. One in five paid them more than USD $1,000.[4]For institution-sponsored agents, these fees may be related to compensation for additional services not covered by institutional agreements – e.g., English language training, and test preparation, help applying for student visas, or help making travel arrangements.

- Top concerns among those who worked with independent agents focused on quality control; while top concerns among students who worked with sponsored-agents revolved around conflicts of interest. Specifically, students complained about misrepresentation of information about universities, untimely feedback, document fraud, unclear fee structures, false promises about guaranteed admission, and unrealistic expectations about on-campus jobs or scholarship opportunities.

This report details these findings, explaining differences among students from five different regions of the world.

Use of Education Agents: Variations by Region and Country

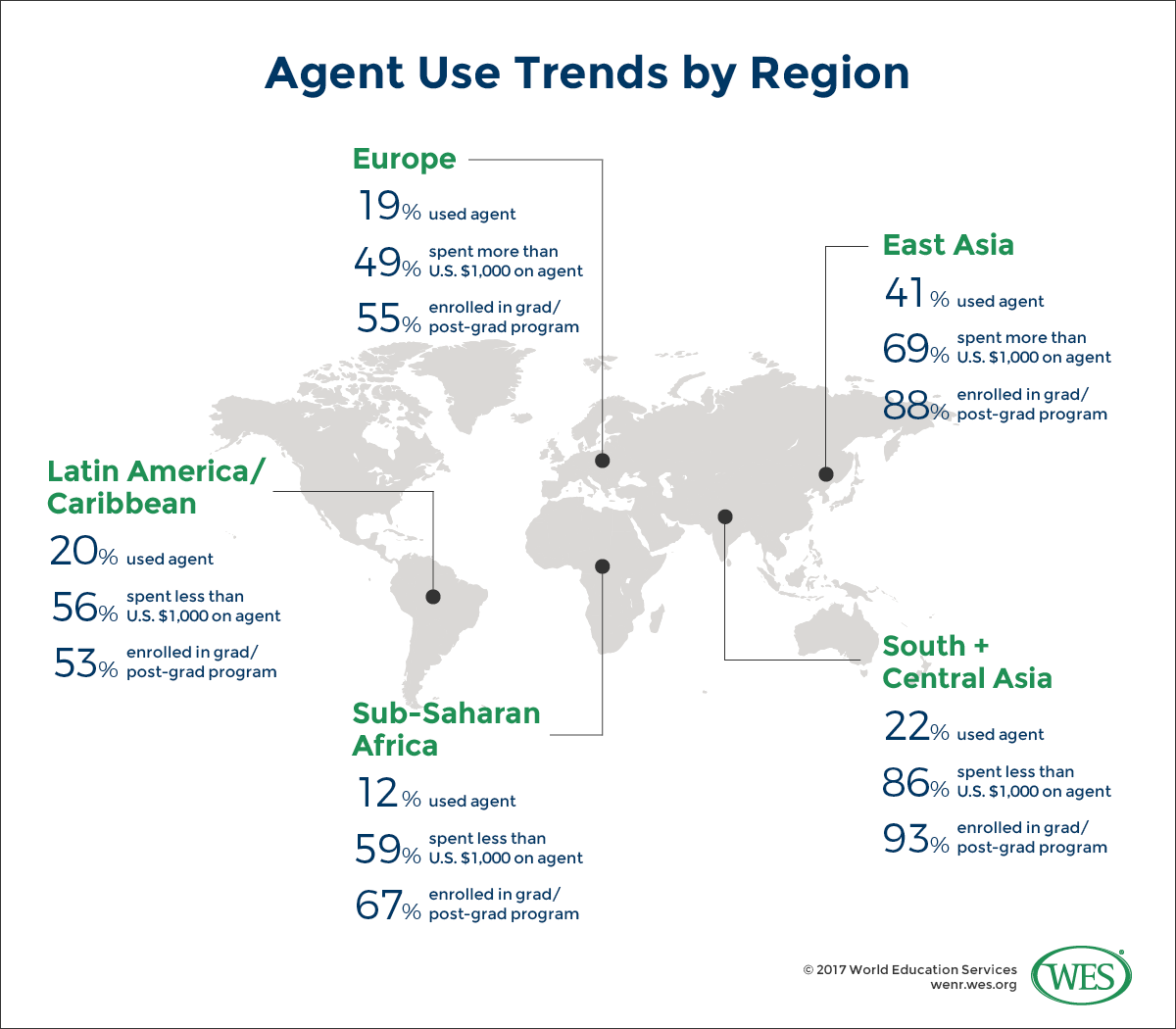

Agent use among our respondents varied considerably, both from region to region, and within regions, from country to country. For instance, 41 percent of East Asian respondents reported using agents, with a high of 48 percent in Japan, and a low of 18 percent in South Korea. Just 20 percent of respondents from Latin America and the Caribbean reported using agents. Rates ranged from 17 percent of Mexican respondents who used agents to 56 percent of Peruvian respondents who did. Among Europeans, 45 percent of Swiss respondents used agents, while only 16 percent of those from the U.K. did.

A detailed breakout of usage rates is below:

Agent “Types,” Compensation Models, and Fees

“I got all I was promised. But the fees were too expensive. Now that I’m in the US, I know that the process is quite inexpensive.” – Undergraduate student, Nigeria

It’s important for institutions and agents to understand the nuances of how students from around the world work with, and pay, different types of agents – particularly given the prevalence of independent agents and of “double dipping” among commissioned agents. (See sidebar.)

Our findings provide insights into the type of agents (independent, commissioned, local, national, international) most commonly used in different regions; into how students compensate agents, whether institution-sponsored or independent; into the size of fees paid to agents; and into how those fees tie to satisfaction with the services provided.

Types of Education Agents

Education agents operate using a variety of business models. They may be commissioned by and on contract with individual institutions. They may be independent operators, who have no university affiliation. They may run local “boutique” operations, or be part of national or international “chains.” They may also subcontract with “super agents” who have a contractual relationship with a single institution, and who subcontract local operators to recruit on their behalf.

Our research sought to uncover the prevalence of certain types of agents within different regions and countries. This goal was particularly interesting, since much of the existing research has focused on the use of agents in Asia, rather than trends in other markets.[5]“Asia” in this context includes both East Asia, and Central and Southern Asia. Here are some of our key findings. We also sought to understand how applicants pay different agent types:

- More than one third of respondents in the five regions studied used agents with a local rather than national or international presence: Overall 35 percent of survey respondents used agents having a “local business,” followed by 29 percent who used agents with an “established nationwide presence.” In terms of the differences between regions:

- South and Central Asia: Well over half of respondents (57%) reported using agents with either an “established nationwide or international presence.”

- East Asia: 44 percent respondents reported using agents with a “local business.”

- Europe: 38 percent reported using agents with an “established nationwide presence.”

- Latin America and the Caribbean: 34 percent of respondents used agents who have an “international presence with multiple offices.” Another 21 percent used agents who have a “one-person operation.”

- Sub-Saharan Africa: 33 percent of students reported using agents who have an “international presence with multiple offices.” One in four (25 percent) used agents who have a “one-person operation.”

- The majority of respondents understood how their agents were compensated. Only about 12 percent were unsure.

- A significant majority (70%) of respondents used “independent education agents,” rather than institution-sponsored agents (16%).

- More than three in four (78%) of East Asian respondents reported using independent agents; fewer than one in ten (8%) used institution-sponsored agents.

- In South and Central Asia, about 70 percent of respondents used independent (a.k.a., non-commissioned) agents.

- Among respondents from Latin America and the Caribbean, 57 percent used independent education agents.

- Almost half of Europeans (49%) reported using independent agents.

- The highest reported use of institution-sponsored agents was among students from Sub-Saharan Africa; 40 reported using institution-sponsored agents.[6]The use of agents from U.K. institutions to recruit students from Sub-Saharan Africa has expanded the commission based agents market within this region, as noted by Moira Hulme, Alex Thomson, Rob Hulme & Guy Doughty in “Trading

Compensation Models

Finding: Students compensate their agents whether or not those agents receive a commission from an institution.

Much of the discussion about education agents in the U.S. revolves around institution-sponsored agents, and assumes a distinction between agents who work for commissions and those who are hired by and paid for by individuals. However, our survey revealed that applicants often experience far less clarity: Ninety-two percent of respondents said that they compensated independent agents for services. More than two thirds of those working with commissioned or institution-sponsored agents also paid for services. [7]Regional variations in this type of payment were high.

Overall, a significant majority of respondents across the globe (85%) indicated that they felt that compensation was essentially fair: They paid their agents for the services they used.[8]Thirteen percent indicated they did not pay, and two percent were not sure. That 83 percent of students were either satisfied or very satisfied with their agent’s services supports this finding. (Student satisfaction and agent services are discussed in greater detail below.)

Amounts Paid

Almost half of all respondents (45%) paid USD $500 or less for agents’ services; another 35 percent paid between $501 and $5,000.[9]Thirteen percent paid $501-$1,000, 13 percent paid $1,001 – $3,000, eight percent paid $3,001 – $5,000, 10 percent paid more than $5,000; four percent indicated that they were not sure what they paid.

Beyond that:

[11]Agents with “local businesses or with “one-person operations” carry a cost premium of seven to 12 percent compared to those with a nationwide or international presence.

[11]Agents with “local businesses or with “one-person operations” carry a cost premium of seven to 12 percent compared to those with a nationwide or international presence.- A surprising number of respondents paid commissioned agents relatively large fees. Almost one in five respondents (19%) paid commissioned agents more than USD $1,000. By comparison, one in three (33%) paid independent agents more than USD $1,000.East Asians reported paying the highest agent fee: 93 percent of students from East Asia reported paying their education agents; 27 percent of those who paid spent more than USD $5,000 for their agent’s services. Anecdotal data indicates that East Asian students may pay truly exorbitant fees for application-related services – in some cases as high as USD $60,000 [12]. One reason may that they use more services from their agents relative to students from any other region. (Types of services offered and used are discussed in greater detail below.)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, reported levels of dissatisfaction with agents typically aligned with whether or not students paid their agents themselves, and if they did, to how much they paid. For instance:

- Students who paid their agents reported higher dissatisfaction (16%) than did those who did not pay (9%). East Asians, who comprise the majority of students paying for their agent’s services, reported the highest rates of dissatisfaction for the value for money they received from the agent’s services (27%).

- Students who used independent education agents rather than institution-sponsored agents reported more dissatisfaction in terms of “value for money” (%).

- Dissatisfaction increased as the amount spent increased – 26 percent of those who paid more than USD $5,000 reported dissatisfaction versus 12 percent of those who paid less than USD $500.

Differences in Agent Use by Level of Study

- Average use of agent’s services is high at the undergraduate level: (80%) undergraduate level than (73%) graduate level.

- Independent education agents are used more by graduate students: (73%) at graduate level than undergraduate level (53%).

- The usage is different by business operations: 36% of students at the graduate level use agents with a “Local business” whereas 30% of students at the undergraduate level use agents which have an “International presence with multiple offices.”

- Students at graduate level pay relatively less for agent’s services: The majority of students (47%) at the graduate level reported paying less than $500 for agent’s services, by contrast 29% of students at undergraduate level paid less than $500 and 24% paid $1,001 – $3,000.

- For certain services undergraduate student’s usage was more:

- Advisory services: “Financial aid and scholarship opportunities at institutions” (90% undergraduate, 78% graduate) and “standardized test-taking preparations” (82% undergraduate, 67% graduate)

- Pre-arrival services: “Housing and accommodation” (65% undergraduate, 47% graduate) and “travel arrangements” (61% undergraduate, 48% graduate)

Student Motivations and Agent Selection Criteria

“Browsing on my own helped me to understand the college selections better and helped me to gain confidence about what I’m doing.” – Graduate student, India

Lack of knowledge of the U.S. education system and word of mouth recommendation are key factors in choosing an agent.

Prospective international students and their parents tend to have access to a great deal of information about U.S. colleges via the media, digital channels, and word of mouth. Yet they need reassurance, additional advice. Much of the available information is not published in any language other than English, and the specifics of the college application and selection processes, and of visa applications and embassy interviews can be daunting. Respondents around the globe reported a number of consistent motives for seeking out an agent, strategies for finding an agent, and reasons for selecting a particular agent, and:

- 45 percent of students cited “lack of knowledge about the college application process in the U.S.” as a main reason for choosing to work with an agent.

- 55 percent reported that they found their agents through word-of-mouth “recommendations by friends, family, teachers, etc.”

- 73 percent said that the main characteristic they look for is “knowledge and expertise of U.S. admission guidelines and education system.”

Among the more than 4,500 respondents who did not use an agent, the majority (78%) felt that they were capable of applying on their own. Just under a third (31%) had friends/family that could help. Other significant issues included the high cost of agents (20%), and lack of trust (14%).

At the regional level, top motivations for working with agents varied by region.

Europe: Knowledge Gaps and “Guaranteed” Admission

“They helped me increase my scores on standardized tests, helped me on my applications, and advised me to be more specific with my statements of purpose and recommendations.” –Graduate student, Greece

- 30 percent of Europeans who used agents said that “promised/guaranteed admission to a specific educational institution” was an important factor in their decision, significantly higher than any other region (16% overall).

- In terms of selecting a specific agent, “recommendation[s] from institutions” (13%) and “internet search” (18%) also played a high role relative to international students overall (5% and 13%, respectively).

Sub-Saharan Africa: Time, Effort, and Reputation for Quality

“Schools in the U.S. trust and favor most admissions based on reference from a reputable agent.” – Undergraduate student, Nigeria

- Among Sub-Saharan Africans, the dominant motivation for using agents was to “reduce the time and effort needed to prepare and/or complete admission applications.” Half of respondents cited this as their top reason to use an agent, compared to 41 percent of students globally.

- 53 percent selected their agents based on the agent’s status as “certified or recognized by international standards” compared to 32 percent of international students overall)

- 28 percent learned about their agents directly from an “institution’s recommendation” or “from institution’s website/brochure/marketing material,” as compared to only 11 percent overall.

Latin America and the Caribbean: Requirements Gaps, Knowledge Gaps, and Referrals

“My agency helped me with the GRE, and gave me an understanding of recommendation letters and statements of purpose.” – Graduate student, Mexico

- The majority of students (51%) from Latin America and the Caribbean region who used agents did so in order to obtain “help meeting specific requirements (such as grade point average, standardized tests, essay completion, etc.)” (Only 23 percent of global respondents cited help meeting such requirements as a reason for using an agent.)

- For these students “knowledge and expertise of the U.S. admission guidelines and education system” is especially important (82%) when making their agent selection.

- As in Sub-Saharan Africa, a significant portion of students from Latin America and the Caribbean region (24%) learn about their agents through institutional sources.

East Asia: Time; Increased Admissions Probability; and Language Barriers

“My agency helped us revise our essays, and figure out which part was most important.” – Graduate student, China

- The desire to “[reduce] time and effort needed to prepare and/or complete admission applications” ranked as the top reason for working with an agent among 48 percent of East Asian respondents.

- “Increase in admissions probability” was a top secondary motivation, reported by 37 percent of respondents (compared to 25 percent overall).

- The need for help overcoming language obstacles was important for East Asian respondents as compared to the overall cohort: 10 percent versus five percent.

- A proven track record in placing students – “the number of students placed in the last year” – ranked as a top selection criteria for East Asian respondents in selecting an agent, especially in comparison to the broader pool of respondents (40% vs 36% overall).

- East Asian students also place a higher emphasis on cost when selecting an agent (39% vs 28% overall).

- Internet searches or “online source[s] such as social media, website, e-newsletter, etc.” helped a significant portion of East Asian students to find the agents they selected. Some 35 percent found agents through these tools, as compared to 23 percent of all respondents.

South and Central Asia – Knowledge Gaps; Visa Application Prep; and Career Counseling

“My agent helped me with aspects that I wasn’t sure about, or had no knowledge about. We were looking for someone who thoroughly knew the entire process of applications as we were not ready to make any mistakes or delay my graduate admissions.” – Graduate student, India

- Students from South and Central Asia indicated that a need for “help in the selection of which schools and/or programs to apply to” was their biggest motivation for working with an agent (46%).

- Respondents from the region reported using agents who “offer [a] variety of services ranging from visa application to admission application process” (47% vs 42% overall). In comparison to the overall cohort, students from South and Central Asia seek “help preparing for visa interviews/application” and “career advice/counselling” at the highest rates (42%, and 35% respectively.)

- “Recommendations by friends, family, teachers etc.” play a very important role in awareness and selection for students from this region; 63 percent, the highest amongst all international students, cited such recommendations as a key deciding factor in selecting an agent.

Services: When Do Students Use Agents Most, and What Services Do They Need When?

Education agents offer a range of services, depending on what stage students are at in the search to enrollment cycle. Some agents offer only services that are directly related to college admissions; others offer services that boost skills needed for academic success; others offer services that are more broadly related to international travel or life abroad; and still others may tack on services related to short- and long-term acculturation and integration

A sample list includes: pre-departure intensive language classes; application form review and submission; standardized tests preparation; visa document assistance, and interview tips; travel planning and flight reservations; banking and insurance planning; pre-departure orientations; and even career guidance.

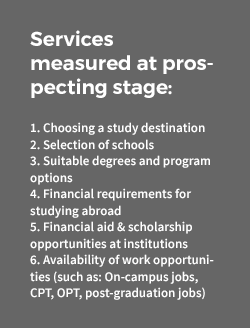

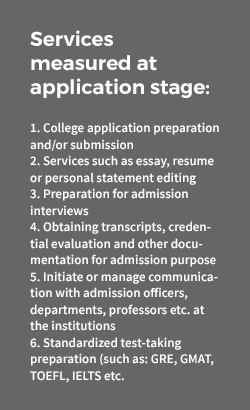

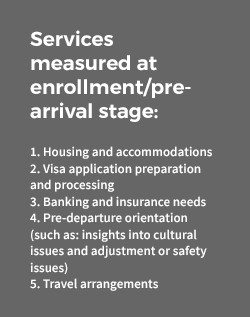

Students use these different services at different stages of the admission cycle – prospecting, application, and enrollment/pre-arrival stage. These interactions also vary by agent type (institution-sponsored versus self-pay) and by region.

The Use of Services Based on Agent Compensation

The use of services among students who paid their agents and those who did not were significantly different at different stages of the prospecting to enrollment period. For instance:

- Information-related services at the prospecting and pre-enrollment stages – Students who (i.e., those who did not pay for services) tended to use these services more than others:

- Financial requirements for studying abroad (81% paid, 84% non-paid)

- Financial aid and scholarship opportunities at institutions (78% paid, 85% non-paid)

- Housing and accommodations (48% paid, 53% non-paid)

- Travel arrangements (49% paid, 53% non-paid)

- Application-stage services – Students who paid their agents used their services more at this stage:

- Essay, resume, or personal statement editing (86% paid, 68% non-paid)

- Preparation for admission interviews (73% paid, 66% non-paid).

Prospecting Stage

Highest agent use, overall, especially among South and Central Asians. Students at this stage rely on agents to help them decide which schools and programs to apply for, rather than for information related to finances or job prospects.

“They provided me with necessary guidance, and educated me on the process. They did not make any false promises, and were upfront about telling me that my ability, profile and GRE score would make the difference, and that they had no role in the admission process. They were there to help me in making informed decisions.” – Graduate student, India

Overall, students who use agents engage at this stage of the applications process more than at any other: 84 percent. Prospecting students from South and Central Asia reported the highest usage rates across all regions at 87 percent. Sub-Saharan Africans reported the lowest usage at this stage at 76 percent. In terms of satisfaction, European students reported the highest satisfaction rates (86%) with the services offered at this stage.

Among the services offered at the prospecting stage, students most often sought assistance related to the “selection of schools” (93%), followed by finding “suitable degrees and program options” (91%). Use of these services was especially high for students from South and Central Asia (95%, 92%), and East Asia (94%, 93%).

Students reported high overall satisfaction levels with services related to selection of study destination, schools, and suitable programs and courses (87%). For “selection of schools,” Latin Americans had the highest satisfaction rates (85%). Sub-Saharan Africans reported the highest satisfaction rates for “selection of degree programs” at 93 percent.

Students sought out agent assistance on other topics less frequently during the prospecting stage. Agent-supplied information such as institutional “financial requirements,” “scholarship opportunities,” and the “availability of work opportunities” had a relatively lower usage at 76 percent. Satisfaction among students who did seek out services related to these topics reported relatively lower levels of satisfaction (72%), with East Asians reporting the lowest levels of -satisfaction (67%).

Application Stage

Application Stage

Highest agent usage among East Asians, especially for services related to personal statement editing, standardized test preparation, and admissions interviews.

“It turns out the application process is pretty straightforward, and I could do it by myself. The cost to hire an agency is way too high.” – Graduate student, Taiwan

Overall, 79 percent of students reported using agent service(s) at this stage. The highest reported usage was among East Asian students (82%); the lowest was among those from Latin America and the Caribbean (74%).

In terms of satisfaction, similar to prospecting stage, European students stood out, reporting the highest overall satisfaction with application-stage services (88%). East Asians reported lowest satisfaction rates (79%).

Note: The underlying reasons for East Asian students’ heavy reliance on agents at this stage include language barriers and unfamiliarity with the U.S. college application process. Media reports indicate that heavy demand for U.S. or Western education among students from China, especially at the undergraduate level, may breed over-reliance on unscrupulous agents [13], who forge transcripts and essays to help students obtain admission. Although outside the scope of this project, it’s reasonable to speculate the higher dissatisfaction rates among East Asians at this stage may relate to the prevalence of bad actors.

Preparatory services:

“The agent helped me meet the application requirements, but just meet them. They were not willing to, or maybe could not, completely realize my ideas.” – Graduate student, China

- Eighty three percent of students who use application-stage services reported using those related to “essay, resume or personal statement editing” with East Asians reporting the highest usage (93%) and Sub-Saharan Africans the lowest (67%).

- The overall assistance needed for “preparation for admission interviews” at this stage was comparatively low (72%). Higher usage amongst East Asians (78%) corresponded to relatively high dissatisfaction with these services (28%). Almost half of the respondents from Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean region did not use agents to prepare for interviews (44%, 43% respectively).

- The least used service by students in this stage was assistance for “standardized test-taking preparations” (69%). Dissatisfaction with test-prep services was highest among East Asians (28%) and lowest among Sub-Saharan Africans (7%).

Application submission:

“They helped me in applying to different colleges, guiding me about which college to apply to, based on my scores and profile. They got me updates about each and every step.” – Graduate student, India

- A substantial majority (92%) of international students who use agents during the application stage seek assistance related to “college application preparation and/or submission.” Usage of this service was especially high for students from South and Central Asia (93%), followed by East Asia (91%). Student’s satisfaction rates were highest with assistance on “college application preparation and/or submission” (89%). The lowest satisfaction rates were with “initiating or managing communication with admission officers, departments, professors etc. at the institutions” (76%).

- Document-related services such as “obtaining transcripts, credential evaluation, and other documentation for admission purpose” were also used at high rates (84%). Europeans students reported the highest usage, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean students (92%, 88% respectively). Sub-Saharan African students reported the highest satisfaction levels with these services (89%).

Enrollment/Pre-Arrival Stage

Most used for visa application preparation and processing; highest usage among Europeans.

“I got every type of guidance regarding my applications. They also provided help with the visa process, and other things like finding roommates.” –Graduate student, India

Relatively fewer international students used agents’ services at the enrollment/pre-arrival stage (57%). The highest reported engagement at this stage was among European students (65%). Students from Latin America and the Caribbean used these services the least (36%).

- Out of all the services offered at this stage, the most used service among all groups of international students was “visa application preparation and processing” at 68%. Respondents from South and Central Asia (74%) were especially apt to seek help at this stage. 90 percent of all respondents at reported the high satisfaction rates with visa application services – the highest rated service at the enrollment stage. South and Central Asians reported high satisfaction (93%).

- European students had the highest usage of agents services related to “housing and accommodations” (63%). This was also the service with high dissatisfaction at (29%) particularly for East Asian students (34%).

- Another area where East Asian students reported significantly higher levels of dissatisfaction was for “pre-departure orientation such as insights into cultural issues and adjustment or safety issues” (22%).

Touchstones for Satisfaction: Agent Integrity, Knowledge, and Influence

A substantial majority of respondents (83%) were either satisfied or very satisfied with their agent’s services. The highest overall satisfaction was for students from South and Central Asia (86%), whereas students from East Asia reported relatively lower rates (76%). Interestingly, South and Central Asian students tend to look for “one-stop-shop” services from agents, a possible indication of higher overall satisfaction with their agent experience in comparison to students from other regions. (See Sidebar.)

To better understand the factors that influenced these satisfaction rates (both positive and negative), we asked students about three key facets of their agency interactions: integrity, knowledge and expertise, and influence.

Agent Integrity

“They helped me save a lot of time. However, I could have applied for PhD program, but they advised me to apply for master’s programs only. I think they were chasing a higher admission rate.” – Graduate student, China

Research about education agents often focuses on ethical issues that affect the admissions process: Document fraud, falsified transcripts, false credentials, forged recommendation letters and personal statements, are all focal points. By contrast, we sought to understand the factors influencing students’ perceptions of integrity [14]. We did so by questioning respondents about two facets of their interactions with agents: the agent’s ability to recommend “best-fit schools based on [students’] interests and capabilities,” and the agent’s ability to “provide current, accurate, and honest information throughout the process that enable them to make an informed choice.”Australia [15], Britain [16], Ireland [17] and New Zealand [18] in 2012.

Overall, more than 80 percent of respondents agreed that their agents recommended best fit schools, and that they provided current, accurate, and honest information. As with most findings, regional variations were notable. In particular, we saw that:

- Among students from Europe, agreement that agents recommended best fit schools was notably high (90%). As discussed earlier, the majority of students from Europe reported using agents who have either an “established nationwide presence” or “international presence with multiple offices” (62%). The reputation that such agents often command – including the high profile they may maintain among U.S.-based institutions – may help to explain why students from this region had a higher agreement than other international students

- Students from both South and Central Asia, and East Asia reported a relatively higher disagreement with both aspects (18%, 17% respectively) of integrity. This finding aligns with experience of higher institutions around the world [19], which grapple with concerns about the ethics and integrity of many agents in various Asian countries.

Agent’s Knowledge and Expertise

“My agent did not clearly explain STEM and non-STEM programs at the school.” – Graduate, post-graduate student, India

“The agency was very proficient and well equipped with knowledge about US institutions.” – Undergraduate student, Nigeria

Among the keys to student satisfaction are an agent’s overall level of knowledge and expertise about various aspects of study in the United States, about the application process, and about the programs that students apply to and enroll in. On this front, it is perhaps unsurprising that we found that students’ satisfaction levels were tied to whether or not agents had an institutional affiliation. For instance:

- A substantial percentage of students from two regions – Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean – work with institution-sponsored agents. Not coincidentally, these students indicated high levels of satisfaction about the knowledge and expertise offered by their agents: 90 percent of students from Sub-Saharan Africa agreed that their agents “had adequate knowledge and expertise that helped guide them through the entire study abroad process;” 81 percent of students from Latin America and the Caribbean agreed that their agents “played a significant role [in setting] them up for success at their institution” – for instance,

- By contrast, 78 percent of East Asians reported working with “independent education agents,” many with local businesses. These students reported higher dissatisfaction with agents’ knowledge and expertise about study abroad, and about their agent’s ability to give them the information needed for success upon arrival at the institution.

These findings likely tie to the fact that institutions expect and demand some level of accountability from the agents with whom they have formal, contractual arrangements, and that they tend to keep those agents up to date on needed information; independent agents lack both contractual accountability, and easily available sources of information.

Agent Influence

“What the agent could help me with was limited. After I did some research, I was sometimes more familiar with the schools and programs I applied to than the agent.” – Graduate student, China

We also measured students’ perceptions of agents’ role in helping them obtain acceptance, and in influencing their decisions about whether to enroll in a particular institution.

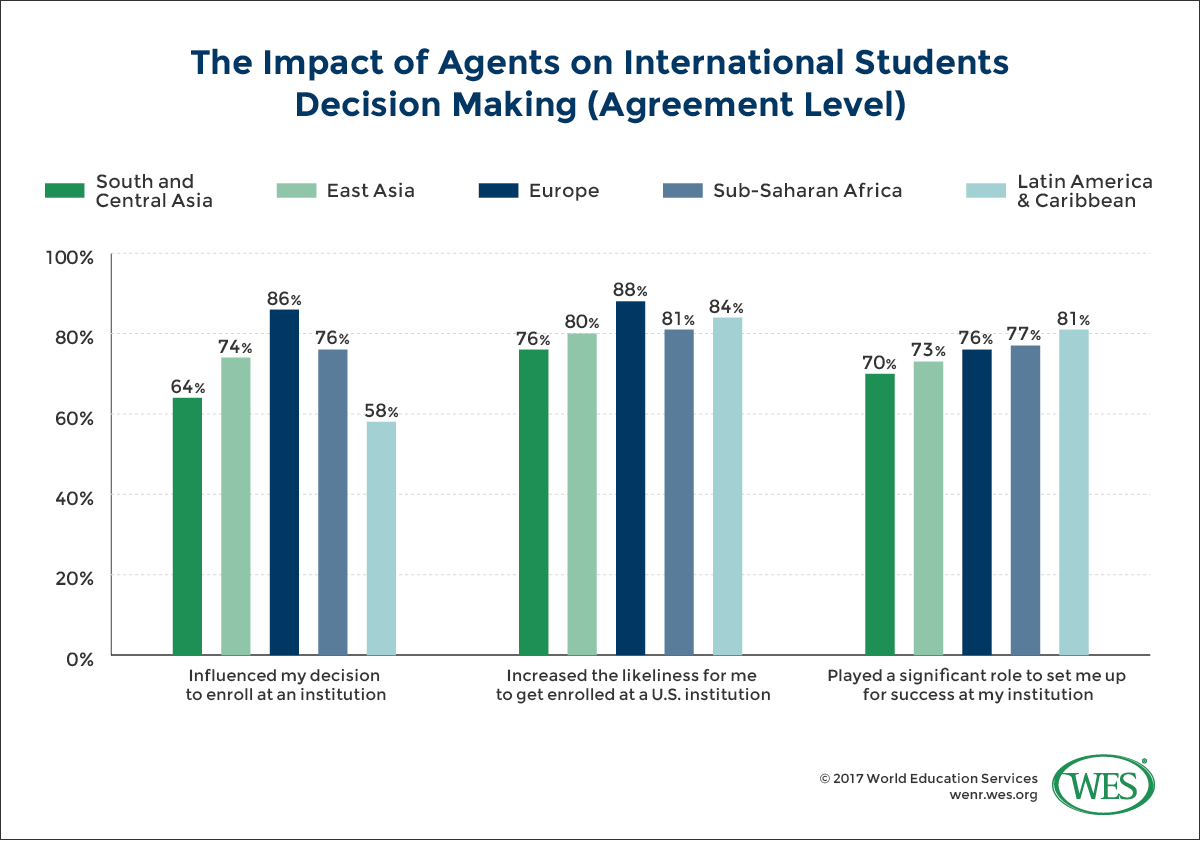

- Students from Europe were the most likely to agree that their agent “influenced their decision to enroll” (86%) and “increased the likeliness to get enrolled” (88%) at a U.S. institution.

- South and Central Asians respondents – i.e., those who were among the most likely of all respondents to work with agents – were the least likely to agree that their agents had an influence on their acceptance by the institutions they applied to (i.e., “increased their likeliness to get enrolled at an institution”) or that their agents “influenced their decision to enroll at an institution.” Of these students, 36 percent disagreed with the proposition that their agents “influenced their decision to enroll at an institution,” and 24 percent disagreed that their agents “increased the likeliness for them to get enrolled at a U.S. institution.”

- Similarly, students from Latin America & the Caribbean region had a low dependency on agents for decision making; almost half (42%) disagreed that their agents “influenced their decision to enroll at an institution.”

Where Agents Fall Short

“It was too expensive, and I ended up doing everything on my own.” –Graduate student, France

“They did not help me as I expected them to. They also discouraged me from applying to better schools, saying I wouldn’t get an admit. I applied anyway, and got an admit.” –Graduate student, Korea

“My agents are too business-minded, and work for the sole reason of improving their income. I would have liked it if their service was student-centered.” –Undergraduate student, Sri Lanka

Students reported multiple challenges working with agents, ranging from lack of clarity in communications and fee structures, receipt of incorrect information about institutions, document fraud, and more. The prevalence of these challenges differed depending on agent affiliation (independent versus institution sponsored), and region or country of origin.

Challenges Working with Independent Agents: Quality Control

“The agent assured me that he would help me find scholarships, but he was not very thorough. He wasn’t available in a timely manner when I needed him in critical moments.” – Graduate student, Venezuela

Overall, the top three challenges faced by international students are internal to an agent’s business operations. All were significantly higher for those who work with independent education agents.

Top complaints were that agents:

- were unresponsive to their queries (28%)

- had unclear financial arrangement or fee structure (23%)

- frequently misrepresented information related to institutions (21%)

East Asians working with independent agents reported the greatest number of these quality control complaints. They also reported concerns about “document fraud or unethical practices” at more than twice the rate of respondents from other parts of the globe (11% vs. 5% overall). These complaints are notable especially in light of two factors: similar concerns among institutions, and the multiple efforts to standardize and improve the quality of third-party education consultants in East Asia. Among the most notable of these efforts are BOSSA – the Beijing Overseas Study Service Association in China [21], Hong Kong International Education Consultants’ Association in Hong Kong.

Concerns about “misrepresentation of information related to institutions” were highest among Latin America and the Caribbean who work with independent agents was (24%) – perhaps a reflection of the fact that many degrees or qualifications from U.S. institutions are not recognized in Latin America [22] – a fact that many students do not discover until well into their studies.

Challenges Working with Institution-Sponsored Agents: Conflicts of Interest

“The agent had ties with various universities, and insisted that I apply at those universities.” –Graduate student, India

Among those respondents who worked with institution-sponsored agents, the top complaint was that agents conveyed “unrealistic expectations about on-campus jobs and/or scholarship opportunities” (29% in comparison to 20% of those who worked with independent education agents).

“Unclear financial arrangements” was another top complaint among (27%). Given the fact that two-thirds of respondents reported paying fees to these agents (and almost one in five respondents reported paying more than USD $1,000), this finding is perhaps unsurprising: The phenomenon of double dipping [23], wherein agents are compensated by both parties (institutions and students), is well known. In such cases, the financial arrangements may not be clearly communicated by agents made clear to students.

Students working with institution-sponsored agents also cited complaints about “false promises about guaranteed admission at their top choice of schools” at a higher rate than those who worked with solo practitioners (16% versus 11%.) Such promises are reportedly often made by institution-sponsored agents in order to sell their partner institutions to the students [24]. This particular complaint was cited by a comparatively high percentage of Europeans (15%) – perhaps unsurprising given that Europeans often select agents with the expectation of obtaining a guaranteed admission to institutions.

Conclusion

Much of the conversation about education agents focuses on those who are institution-sponsored. However, our findings indicate that far the greatest percentage of students work with independent agents. It’s important to shift the conversation to address challenges in the broader market as it exists and functions today. Both sponsored and independent agents affect admissions in U.S. institutions, and by extension, campus life. Both types of agents can be effective advocates for students and for institutions, helping to ensure a best-fit match for both. Or they can be ineffectual guides to a complex system, causing institutions to miss out unnecessarily on strong candidates, and causing students to lose opportunities or make bad choices.

Clear rules of engagement with both independent and commissioned agents can help institutions ensure that qualified international students are able to apply and enroll, regardless of which type of agent they choose.

Recommendations

- Take the time to understand how students work with agents in different regions. For instance, while students from South and Central Asia mostly need their agent’s services during the prospecting stage, students from East Asia need the most assistance during the application stage. Europeans have the biggest need during the enrollment stage while students from Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America need agents for specific tasks such as obtaining transcripts, credential evaluation, or preparing for standardized admission tests.

- If you do work with commissioned agents, ensure you thoroughly vet them and their business practices. Ensure that your operating agreements with them stipulate agreed-upon compensation mechanisms for agreed-upon services; evaluate and monitor implementation of those practices on an ongoing basis; and provide training, on a repeated basis if necessary, to mitigate the challenges most often reported by students. In particular: determine whether commissioned agents receive additional payments from a student/family for counseling services, and whether they offer any explicit or implicit guarantee of admission, and take corrective action, if either turns out to be the case (NACAC 2013).[11]Report of the Commission on International Student Recruitment to the National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC) May 2013

- Assess how your institution will seek to educate independent agents, since students in most regions use them far more often than they do sponsored agents. Identify top agents regardless of affiliation, and the determine how to provide them with up-to-date information about multiple facts of your institution: courses and programs; financial aid and scholarships; career services; student life; English-Language training; housing; etc. Ensure your website provides clear, easy-to-find information about these topics for students and parents as well.

- Use your website to educate parents and prospective students about the differences in agent business models. Explain that some agents are independent education agents/consultants; some are institution-sponsored agents. Advise them to validate the list of university partners that agents work with by cross-checking them with schools. Advise them to use an agency that clearly describes all the services they provide and the associated fees. Advise them to request that they be included in all agent communications with universities in order to avoid any misrepresentation of information.

References

| ↑1 | The definition of education agent was provided to the respondents as “an individual, company or organization that provides educational advice, support or placement to students in a local market who are interested in studying abroad.” Also, for the sake of simplicity, the terms “agency,” “agent,” “international student recruitment agency,’” “education agency” or any third party “education advisor” and “education consultants” were referred to as “AGENT.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | There are some exceptions to this rule. One 2014 study, for instance, examines the use of agents from U.K. institutions to recruit students from Sub-Saharan Africa. (Moira Hulme, Alex Thomson, Rob Hulme and Guy Doughty (2014) Trading places: The role of agents in international student recruitment from Africa, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 38:5, 674-689, DOI: 10.1080/0309877X.2013.778965) |

| ↑3 | NOTE: This survey was self-reported and was incentivized with prize drawings of five USD $50 Amazon gift cards, which may have induced bias in responses. The definition of agent or definition about their business operations/type might not be clear to some respondents. For the simplicity of the survey, an agent’s definition was generalized for students as many students may not be able to distinguish between different types of agents and hence the survey does not bring out differences between agents/counsellors/advisors from an institutional perspective. Since the survey went out to WES credential evaluation applicants, there could be a higher representation from certain students that have both a higher awareness and usage of WES services. |

| ↑4 | For institution-sponsored agents, these fees may be related to compensation for additional services not covered by institutional agreements – e.g., English language training, and test preparation, help applying for student visas, or help making travel arrangements. |

| ↑5 | “Asia” in this context includes both East Asia, and Central and Southern Asia. |

| ↑6 | The use of agents from U.K. institutions to recruit students from Sub-Saharan Africa has expanded the commission based agents market within this region, as noted by Moira Hulme, Alex Thomson, Rob Hulme & Guy Doughty in “Trading |

| ↑7 | Regional variations in this type of payment were high. |

| ↑8 | Thirteen percent indicated they did not pay, and two percent were not sure. |

| ↑9 | Thirteen percent paid $501-$1,000, 13 percent paid $1,001 – $3,000, eight percent paid $3,001 – $5,000, 10 percent paid more than $5,000; four percent indicated that they were not sure what they paid. |

| Australia [15], Britain [16], Ireland [17] and New Zealand [18] in 2012. | |

| ↑11 | Report of the Commission on International Student Recruitment to the National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC) May 2013 |