Paul Schulmann, Research Manager, and Ziyi Christine Ye, Research Assistant, WES

The staggering economic growth of China over the last three decades has transformed higher education around the globe. Year after year, the country’s newly minted middle class parents have been willing and able to send their children abroad, en masse, in search of the best degrees available. The speed with which these students have inundated the market have been stunning, and the campus impact often overwhelming. In 2016, a reported 544,500 Chinese students sought degrees abroad [1], up from 38,989 in 2000 [2] and on track to reach as many as 800,000 within five years [1] – at which point the great outpouring may finally begin to taper off.

More recently, China has embarked on an effort that could have an equally radical effect on global higher education: transforming itself from a non-entity as an international higher education destination into a major player. In 2012, China’s officials announced a goal of becoming an international education hub [3] with an enrollment of 500,000 international students by 2020. If this plan is successful – and if the country established new, more ambitious goals – the impact on global student mobility, which encompasses an estimated 4.5 million [4] students from around the world as of 2012, is likely to be substantial. Even so, many observers remain skeptical about whether China can truly unseat traditional education destinations as a top draw for international students, arguing that it may simply become one node in an increasingly diverse, dynamic, and borderless higher education landscape.

This article examines the factors related to either outcome.

Factors in Favor of Chinese Dominance

In 2012, China’s officials announced a goal of becoming an international education hub [3], with a target enrollment of 500,000 international students at all levels of education by 2020. Since then it has attracted hundreds of thousands of students from across Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Americas. By almost any relevant measure, the country has made enormous progress against its goal, and appears poised to make even more. Consider:

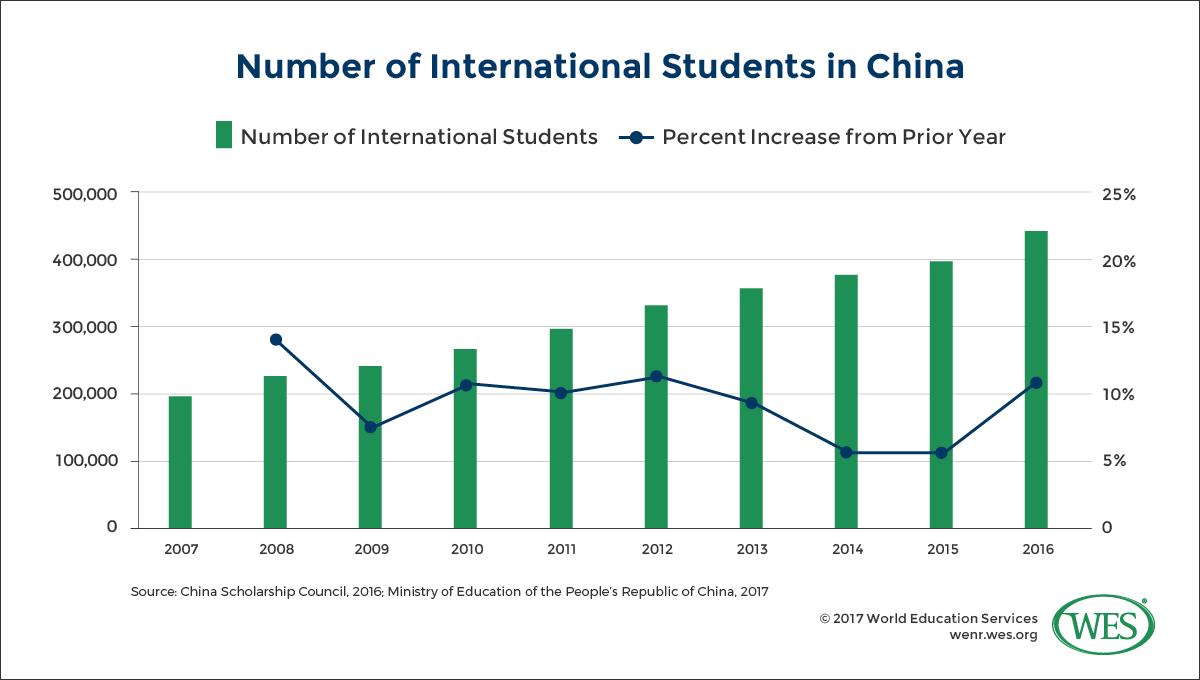

- Volume: According to data from the China Scholarship Council and Project Atlas [5], international enrollments more than doubled from 2007 to 2015, when they reached 397,635 international students. China’s Ministry of Education states that those numbers surpassed 400,000 [6] in 2016, making China the third most popular [7] destination country for international students after the U.S. and the United Kingdom. student.com [8], project that in 2020, China will overtake the U.K. to become the second biggest host country for international students. The country is also a leading host of international branch campuses [9].

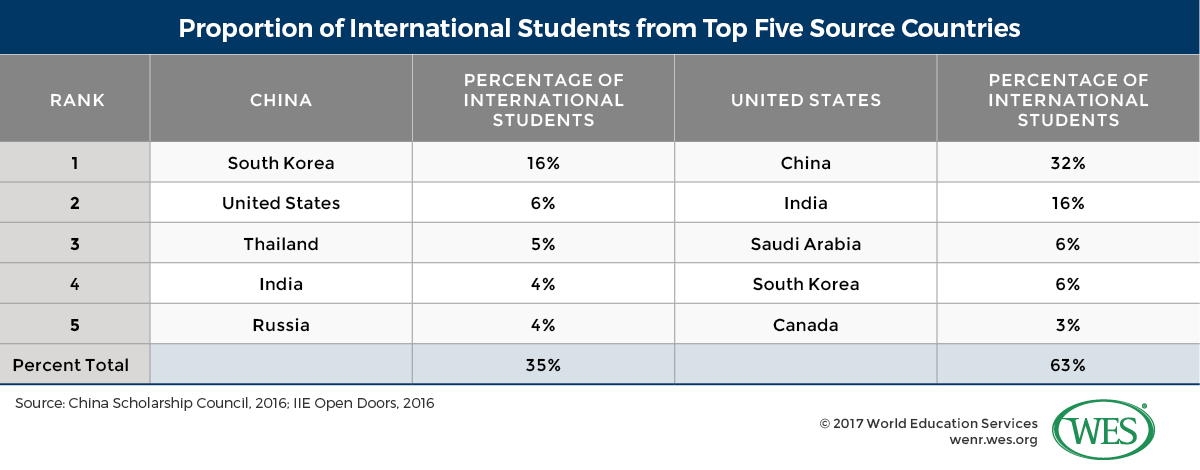

- Diversification of source countries: China has managed to attract students from an array of countries around the world. While over half the international students in the U.S. come from China or India, countries of origins of international students in China are more diverse – the top five countries for international student enrollment in China constitute only roughly a third of enrollment. These figures indicate the strength of Chinese internationalization efforts. Overreliance on students from one or two countries is a potentially combustible formula for internationalization, particularly in the face of political, economic or other events that can devastate institutions’ international enrollment funnels.

- Government investment: One of the main forces contributing to the fast and steady growth of international mobility to China is the steady improvement of China’s higher education system thanks to governmental investments. Facilitated by China’s rapid economic growth, China’s reformist leader Deng Xiaoping emphasized in 1983 that “education must face modernization, face the world and face the future.” [2]Tsang, M. C. (2000). Education and national development in China since 1949: Oscillating policies and enduring dilemmas, The China Review, 579-618. His reform agenda first manifested in the 1993 “Outline for Education Reform and Development in China.”[3]Iftekhar, S. N., & Kayombo, J. J. (2016). Chinese-Foreign Cooperation in Running Schools (CFCRS): A policy analysis. International Journal of Research Studies in Education, 5(4), 73-82. Ongoing initiatives have sought to transform Chinese higher education into a world class system.

These successive reform efforts have greatly improved the quality of higher education in China, and have in turn, made them an attractive option for international students. twelfth [12] Five-Year Plan inaugurated in 2011. This plan saw the government announce the goal of building up a technology-driven innovation economy [13], signaling an effort to gradually shift away from a labor-intensive manufacturing economy. As a result, STEM-related fields of study, especially basic science research [14], have received generous funding to cater to the country’s stress on technological development. Additionally, the government has been actively promoting and coordinating cross-border STEM cooperation [15] programs at higher education institutions. Thanks to these efforts, STEM fields have been the fastest growing majors [16] for foreign students coming to China.

- Regional Ties: More recently, China’s One Belt, One Road [17] (OBOR) initiative has sought to tighten the Eurasian collaboration [18] through international trade among 64 countries spanned by the road. The policy has significant implications for the country’s international education agenda. The cultivation of international talent for OBOR countries, critical to implementation of the OBOR framework [19], has furthered China’s internationalization ambitions considerably. In fact, nearly half of foreign students [17] studying in China are from Belt and Road countries whose economies are growing [20] at remarkable speed. Moreover, the percentage [16] of government-sponsored students from OBOR countries is five times higher than that of all foreign students. These facts suggest that China’s international academic exchange intertwines closely with the country’s economic pursuits.

- Visa Policies: China has also sought to increase its attractiveness as a host for international students by loosening visa policies [13] and enabling foreign students to gain valuable work and internship opportunities. These efforts include [21] relaxing rules on obtaining permanent residency in some major cities, a pilot program to replace annual work permit renewals with a five year permit, allowing foreign students to participate in short term internships, and students in Beijing to take part time jobs or create high tech startups.

NOTE: One of China’s most interesting internationalization plays has been its effort to increase enrollment in degree programs from students from countries and regions where both economic development and education systems may be lagging. These students may not have the means to study in North America, Australia, or Europe, and may be attracted to a Chinese education, which is comparatively affordable, particularly thanks to the generous scholarships offered by the Chinese government. In fact, the Chinese government supports about 11 percent [6] of international students through a variety of scholarship programs [22], some of which support students from nations in Africa [23], the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the Pacific Island Countries [22].

A Natural Ceiling? Factors That Could Limit Growth

China’s successes to date, which include robustly increasing the number of international students by enacting various supporting policies, portend well for the future of Chinese internationalization efforts. However, several factors serve as a counterweight to the country’s ambitious goals.

- Political climate: Even as China carries out its internationalization agenda, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has raised the alarm about the potential influence of “Western values” [24] in the country’s education system. To strengthen ideological control [25] among university students, the CCP enacted a set of regulations in June, 2017. These range from constraints on organized religious and political activities on university campuses, to requirements that foreign students to take classes in Chinese language, culture, law, and politics. In particular, 29 top universities [26], including Peking University and Tsinghua University, have undergone as many as twelve rounds of governmental political inspections since 2013. In recent months, the CCP has sought to tighten controls on internet access [27], especially on virtual private networks, which Chinese higher education institutions and academics use to access to foreign research resources. Such political crackdowns have caused public concerns from both foreign organizations [28] and the Chinese academia [27], who fear that they compromise the intellectual and academic freedom and integrity of higher education in China.

- Capacity at elite levels: Elite institutions in China have become more internationally competitive in terms of global rankings [29]; however, at the broader level, the education system continues to struggle in terms of general quality. The now defunct 211 and 985 programs, implemented in 1995 and 1998 respectively, routed billions of dollars to a limited number of top-tier public schools in an effort to increase their international standing and their research output. 451.2 billion CNY (USD $68.8 billion) [30] from both the central government and local governments, comprising about half of the government’s annual research funding. [6]Li, Y. A., Whalley, J., Zhang, S., & Zhao, X. (2011). The higher educational transformation of China and its global implications. The World Economy, 34(4), 516-545.)

- Student satisfaction: Research indicates that many international students express a low level of overall satisfaction with their study-in-China experiences, mainly due to the absence of living and support services [31] from their institutions. As the author of one 2016 paper in the Journal of Studies in International Education noted, “the considerably and consistently low levels of international students’ satisfaction with their study and living experiences show that China has not paid sufficient attention to improving its supply of higher education and other support services, which may threaten its sustainable growth in the international student market.”WES research [32] in the U.S. market supports this finding, indicating that students who are more satisfied with their experiences are more likely to recommend an institution, thus contributing to a more robust and sustainable enrollment funnel at both the institution and county level.

- Language barriers: While Chinese universities have made great strides in offering more programs in English,large influx of Indian students [33] coming to study in China, 80 percent of who major in medicine. Despite this as well as an increase in English-taught business programs [34], Chinese universities by and large operate in Chinese. for many students, the linguistic barrier remains an often insurmountable obstacle to prospective degree-seeking students.[9]Ding, X. (2016). Exploring the experiences of international students in China. Journal of Studies in International Education, 20(4), 319-338. English remains the lingua franca of academia,[10]Jenkins, J. (2013). English as a lingua franca in the international university: The politics of academic English language policy. Routledge.rendering language a significant challenge in terms of China’s goal of increasing international student enrollment.

The Future

China will undoubtedly continue to make impressive gains in terms of both increasing the number of international students, and internationalizing its campuses and campus cultures. But just how much the country’s gain will ultimately hurt other traditional markets like the U.S. remains uncertain, at least in the short term.

On one hand, China’s highly centralized government remains determined to execute on goals and policies that will increase its pull. Funding, and efforts to increase global academic rankings at China’s top-tier universities are ongoing. Moreover, the country’s One Belt, One Road Policy will doubtlessly facilitate educational mobility among the 64 countries along the road, much of it headed for China. On the other, China’s internationalization efforts face real limitations – some, such as curbs on academic freedoms and on access to information, manufactured; others, such as the small number of prospective students capable of studying in Chinese, organic in nature. Uneven quality across the sector remains another challenge that still impacts the vast majority of Chinese institutions. But how things will play out over time remains an open question.

References

| ↑1 | Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, Project Atlas, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies and organizations. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Tsang, M. C. (2000). Education and national development in China since 1949: Oscillating policies and enduring dilemmas, The China Review, 579-618. |

| ↑3 | Iftekhar, S. N., & Kayombo, J. J. (2016). Chinese-Foreign Cooperation in Running Schools (CFCRS): A policy analysis. International Journal of Research Studies in Education, 5(4), 73-82. |

| ↑4 | Iftekhar, S. N., & Kayombo, J. J. (2016). Chinese-Foreign Cooperation in Running Schools (CFCRS): A policy analysis. International Journal of Research Studies in Education, 5(4), 73-82. |

| ↑5 | Bloom, D. E., Altbach, P. G., & Rosovsky, H. (2016). Looking Back on the Lessons of “Higher Education and Developing Countries: Peril and Promise”—Perspectives on China and India. International Journal of African Higher Education, 3(1). |

| ↑6 | Li, Y. A., Whalley, J., Zhang, S., & Zhao, X. (2011). The higher educational transformation of China and its global implications. The World Economy, 34(4), 516-545. |

| ↑7 | Ding, X. (2016). Exploring the experiences of international students in China. Journal of Studies in International Education, 20(4), 319-338. |

| large influx of Indian students [33] coming to study in China, 80 percent of who major in medicine. Despite this as well as an increase in English-taught business programs [34], Chinese universities by and large operate in Chinese. | |

| ↑9 | Ding, X. (2016). Exploring the experiences of international students in China. Journal of Studies in International Education, 20(4), 319-338. |

| ↑10 | Jenkins, J. (2013). English as a lingua franca in the international university: The politics of academic English language policy. Routledge. |