Historically, Asia has faced a student mobility deficit. As of 2015, Asian countries sent an estimated 2.3 million degree-seeking students abroad and attracted just 928,977 in return.[1]Estimated based on the data from the UIS Statistics. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies. However, this flow may be poised to reverse itself in the relatively near term. Individually and as a group, a handful of Asian powers are trying to strike a balance between outbound and inbound student mobility. They are seeking to transform themselves from being pure senders of international students into top education destinations. A surprising number – including China, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and Malaysia – have set explicit goals for dramatically increasing international recruitment between 2020 and 2025.

If they succeed, some 1.4 million international students will, within less than a decade, circulate intra-regionally rather than globally. These strategies are primarily intra-regional – a fact that is important from at least two perspectives.

- From the Asian standpoint, the potential to alleviate brain drain to the West, a chronic challenge for sending countries is hugely appealing. An intra-regional approach keeps those students close to home, and allows them to foster deep person-to-person ties, and the sort of lasting social capital that ultimately pans out in long-term business opportunities and economic benefits. In 2017, PricewaterhouseCoopers [2] updated its long-term economic growth projections, and predicted that power will shift to fast-growing Asia from the advanced Western economies. In the most recent global rankings of the world’s largest economies, 11 Asian countries were expected to enter the top 25 by 2050. This estimate revised 2014 projections, which projected that just 7 Asian countries would make the top 25 by 2050. One of the recognized motives for Asian powers to catch up with traditional study abroad destinations is this type of economic growth.

- From the Western perspective, what’s clear is that significant numbers of students from top sending countries may no longer be in play within just a few years. In all, internationally mobile students from Asia account for an estimated 55 percent of the world total today.[2]Estimated based on the data from the UIS Statistics. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies. China and India are far and away the most dominant senders, but the fact is that, collectively, the region’s developing countries make substantial contributions as well.

Unsurprisingly, China, which has established a goal of attracting some 500,000 international students by 2020, has taken a leadership position in expanding the regional higher education market. Its One Belt and One Road initiative, designed to promote economic development among 60+ Asian and Eurasian nations, will increase student mobility from across the affected region. To date, many of those students have headed directly to China. In 2016, the number of foreign Asian students in China [3] was more than 264,000, a growth rate of 10 percent over the year prior.

Other Asian-Pacific countries are seeking to increase enrollments among students from across the region as well. The Asian Universities Alliance [4] was launched by the end of April. The alliance was established by 15 founding members composed of world-class universities across China, India, Hong Kong, Thailand, Myanmar, Singapore, Kazakhstan, South Korea, UAE, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Japan, and Saudi Arabia. The alliance has pledged to consolidate Asia’s presence and expand influence in higher education across that global stage. Apart from increasing intra-Asian mobility, the ultimate goal is to improve the overall regional growth and competitiveness. It is meant to serve not only as an alliance, but also as a resources exchange platform, facilitating more cross-border research activities and exchange programs are expected between these 15 universities and even within the region. The collaborative efforts show their great commitment to sharing values and common interests.

This article examines progress and trends in Japan, Malaysia, Taiwan, and South Korea.

Japan

In 2014, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe committed to a target of attracting 300,000 foreign students to Japan by 2020 [5]. The country, which first began to expand its cross-border academic activities as early as 1983, is already the most well-established international education hub in the region.which set a goal of attracting 100,000 foreign enrollments within 20 years [6], additional efforts flagged. For instance, one 2008 plan to attract 300,000 new foreign enrollments, fell far short of that number [5].

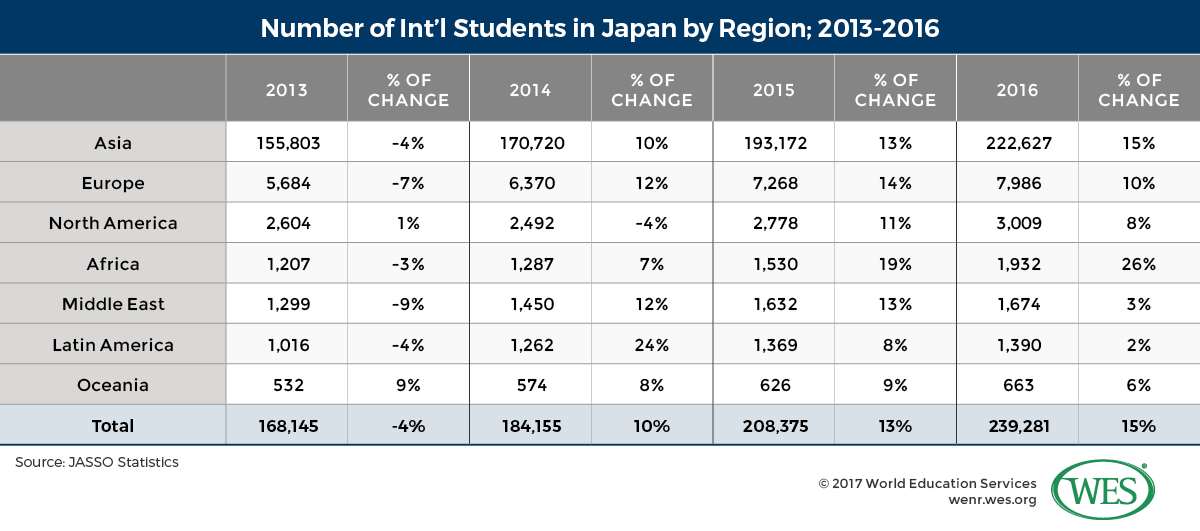

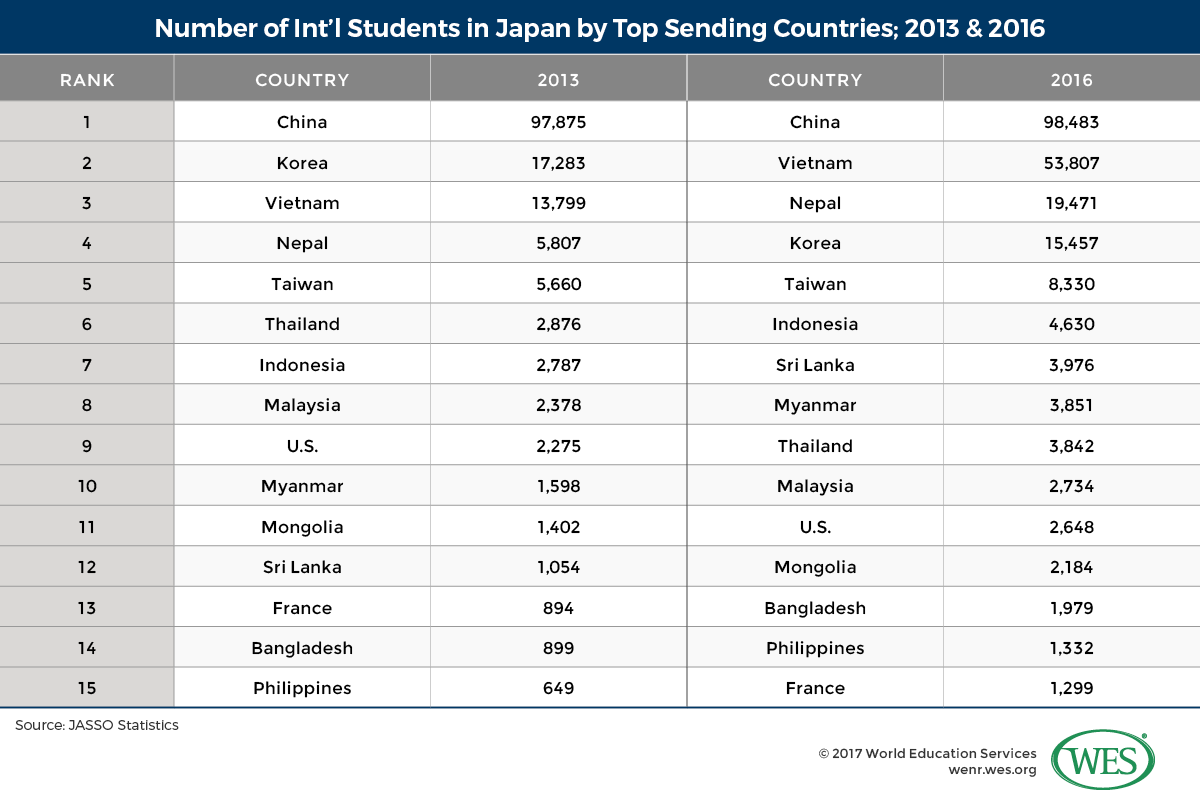

Abe’s effort has so far seen far greater success. By 2016, foreign enrollments in the country’s universities were on a dramatic upward trajectory, having risen to just over 239,000 – a rise of 71,136 students (or more than 40 percent) over 2013 totals. Almost 94 percent of those new enrollments came from other countries in Asia.

Perhaps the most notable thread in Japan’s story is its recent success in diversifying its regional sourcing. In both 2013 and 2016, China was the leading country of origin for foreign students in Japan. However, the count barely budged between 2013 and 2016, while numbers from most other Asian numbers skyrocketed. For example:

- Vietnamese enrollments rose almost fourfold, from 13,799 to 53,807.

- Nepalese enrollments more than tripled from 5,807 to 19,471.

- Taiwanese enrollments rose by about 50 percent, from 5,660 to 8,330.

- Indonesian enrollments by about two-thirds, from 2,787 to 4,630.

The number of students from multiple other Asian countries – among them Myanmar, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, and Bangladesh – doubled, tripled, or even almost quadrupled as well.

Economic growth across the ASEAN region has, say observers, contributed to Japan’s success in attracting students. Expected to become a middle-upper-income country [8] within two decades, Vietnam has an expanding middle class [9] and a strong tradition of supporting children’s academic success at the tertiary level. Structural problems in Vietnam’s higher education sector are likely to drive continued outbound mobility among students. Per ICEF Monitor, [10] “persistent problems include large class sizes, underqualified faculty, and uneven quality standards for [programs].” Japan has sought to capitalize on the situation, actively cultivating the market by working with agents [11] to recruit even greater numbers of Vietnamese students.

Note: South Korean enrollments bucked the growth trend, falling from 17,283 to 15, 457. While enrollment numbers from China remained flat. These trends may be due to strained historical relations with Japan, [12] say observers.

Pull Factors

Japan is highly motivated to attract a new cohort of students to its universities, which are facing a steep shortfall of domestic enrollments. The country has an oversupply of university seats, thanks to rapid expansion of the sector from about 500 institutions in the early 1990s to about 780 in 2014.Nippon.com [14].

To address these deficits, Japan has recently taken an aggressive, multipronged approach to positioning itself as an attractive education destination for students from neighboring countries. The government-funded Top Global University Project [15], unveiled in 2014, is an example. The program provides ¥7.7bn (US$72m) in funding to 37 leading universities. The goal is to transform them into intellectual centers that will attract foreign faculty, researchers, and students, and to increase their standing in global rankings. As of 2016, the Abe government also set out to significantly and measurably improve employment prospects for international students through “incentives such as [subsidized] company internships, help with finding jobs on graduation, stepped-up Japanese language courses, and more streamlined processes for work visas after graduation.”“ [16]Push for foreign students to stay on to work in Japan,” University World News, March 2017 [16]

How Japanese efforts will fare over the long term remains an open question. Regional tensions between Japan and top senders like China and South Korea [17] are one factor. So are improvements in the university systems of other countries throughout the region. “We used to receive a lot of students from China, Korea, and Taiwan but their higher education is getting better and better,” the executive director of student exchange at the Japan Student Services Organisation [18], told the PIE News [19] in 2014. “The situation and environment [are] changing. All the ASEAN countries are thinking about improving their higher education systems. And if the education systems in ASEAN countries are getting better, they don’t need to send their students to study in Japan for undergraduate degree [programs].”

Malaysia

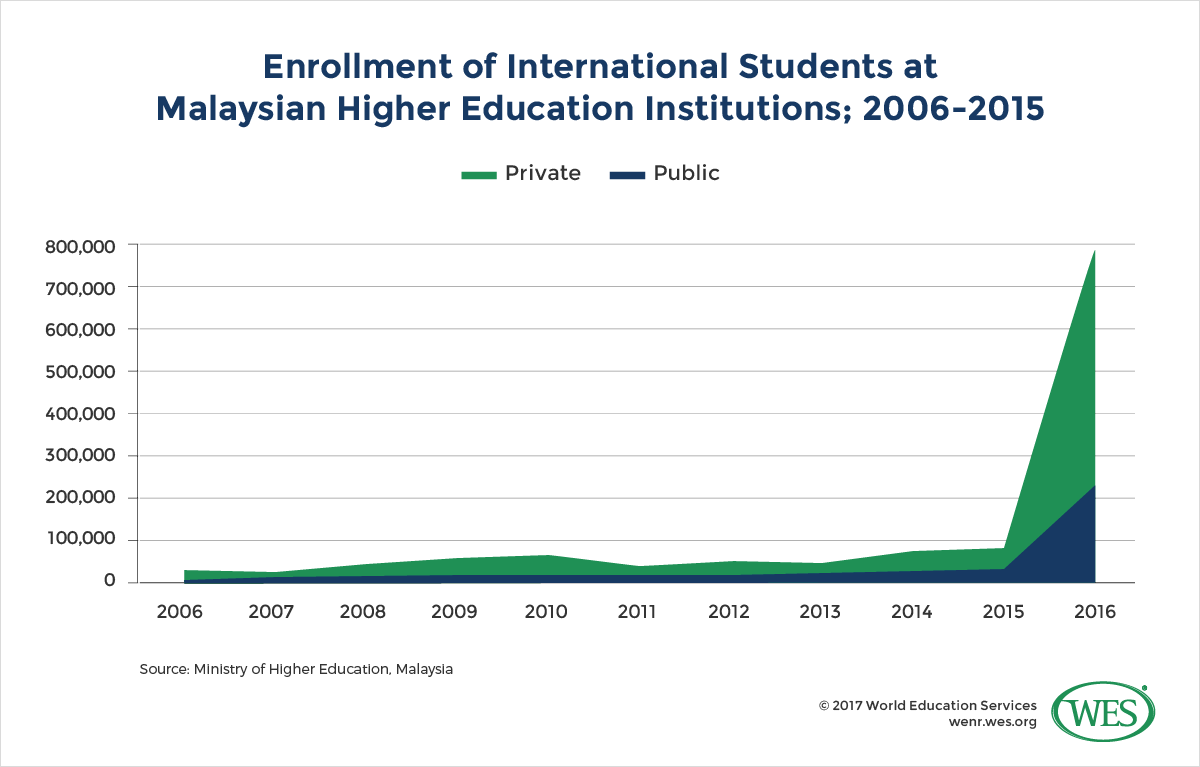

In 2015, the Malaysian government released national education blueprint, with a goal of attracting some 250,000 international students by 2025 [20] (up from an earlier target of 200,000 by 2020.) The country is well on its way to achieving its goal.

One of the five founding members of ASEAN, Malaysia has made substantial progress over a relatively short period of time. The country first made UNESCO’s list of top 20 destination countries for international students in 2014, when it ranked number 12. A year later, it placed ninth, with 151,979 international enrollments. By December 2016, 172,886 international students – 132,710 of them in higher education – were reportedly enrolled in Malaysian schools and institutions [21].

This rise has been rapid. Prior to the mid of 1990s, international students only accounted for less than one percent of the country’s total university population [22]. According to researchers Diana Wong and Ooi Pei Wen, “In 1989, when tertiary education in Malaysia was still a state monopoly, foreign students numbered not more than 466 or 0.8 percent of the total university population in the country… Twenty years later, in 2009, there were 72,000 international students.”[8]The Globalization of Tertiary Education and Intra-Asian Student Mobility: Mainland Chinese Student Mobility to Malaysia* Diana Wong and Ooi Pei Wen Universiti Sains Malaysia, Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, Vol. 22, No.1, 2013

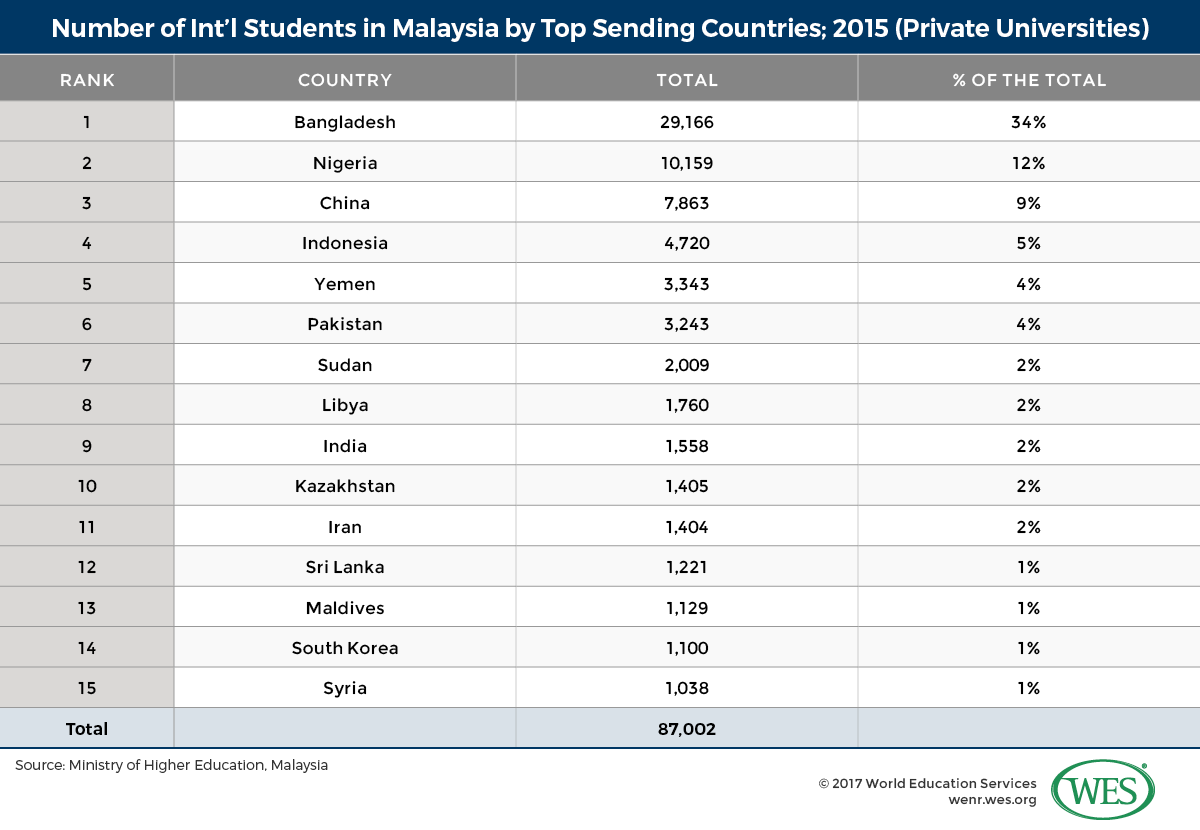

The mix of international students in Malaysia is unique. The country is heavily Islamic, and is a top draw for Muslim students from other heavily Islamic countries. The result is that Malaysia’s higher education system draws a more diverse mix of international students than many of its global or regional competitors. The top two sending countries, Bangladesh and Nigeria, both have large Muslim populations. Among the top 15 sending countries, students from six predominantly Muslim South and Central Asian countries account for 43 percent of the total enrollment, followed by 11 percent from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. The almost 8,000 students from China, Malaysia’s third leading sender of students, are reportedly drawn through family ties to Malaysia’s entrenched Chinese Muslim community. [9]The Globalization of Tertiary Education and Intra-Asian Student Mobility: Mainland Chinese Student Mobility to Malaysia* Diana Wong and Ooi Pei Wen Universiti Sains Malaysia, Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, Vol. 22, No.1, 2013

Pull Factors

Malaysia has deliberately sought to establish itself as an international education hub. Per the British Council’s most recent assessment, Malaysia stands alongside Germany, the Netherlands, and Hong Kong in terms of having “the most balanced portfolio of national policies supporting [International Higher Education.]”allocate 5 percent of the available seats in medical, pharmacy, and dentistry programs to international students [21].

Malaysia’s commitment to internationalization stems from the fact that its government explicitly views international education as a form of economic development. The Ministry of Higher Education, write the authors of a 2014 report for UNESCO, “actively seeks to further increase the number of international students studying in Malaysian colleges and universities… as a source of national income… The model [emphasizes] substantial investment in education as a means of building an educated workforce in the expectation that evidence of an educated workforce, in turn, will attract international investment. This international investment would, then, fuel the economic development of the nation.”http://dx.doi.org/10.15220/978-92-9189-147-4-en [24]

Part and parcel of this approach is a focus on international rankings. “The benefits of upgrading the higher education system will only be achieved as prospective students choose to study in Malaysia, as business and industry locates in Malaysia, and as international investors see the country as offering a high-quality setting for their investment. To this end, it is important to the government that Malaysian higher education be widely respected and internationally ranked.”

To that end, Malaysia has made substantial investments in the development of its higher education system, particularly through privatization. In 1996 for instance, Malaysia’s Private Higher Education Act [25] gave rise to the private higher education that is now such a draw for international students. Following the act’s passage, private institutions proliferated rapidly. Some 30 years later [26], more than 400 private colleges, and another 100 private universities and university colleges are in operation. Perhaps unsurprisingly, enrollments in private institutions make up the bulk of international enrollments in Malaysia. Over the years, these institutions have attracted an enormous number of international enrollments; almost 90,000 by 2015 – more than 70 percent of Malaysia’s inbound total that year.

Malaysia’s Private Higher Education Act also paved the way for the emergence of a wave of branch campus and joint degree programs in the late 1990s and early 2000s. According to a January 17 update from the Cross-Border Education Research Team (C-BERT) [28], Malaysia was tied with Singapore as the third leading importer of branch campuses; each country is host to 12.

In many other countries, rapid privatization of the higher education sector has led to poor quality. Malaysia has actively sought to guard against this trap. In 2013, the government imposed a moratorium – which it extended in 2016 [26] – on the establishment of new private colleges and universities. The moratorium seeks to ensure that existing institutions remain sustainable in the face of downward enrollment trends among both local and international students – part of a broader effort to preserve Malaysia’s overall status as a desirable international and regional education destination. So far, Malaysia’s deliberative approach to reputation has paid off. Over the last decade, the country’s top universities have begun to climb up key global ranking systems, including those published both Times Higher Education [29] and Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) [30].

The outlook for Malaysia’s ambitious goal of attracting 250,000 international students by 2025 remains mixed. As Phil Baty, editor of the Times Higher Education rankings, noted in 2017 [31], Malaysia’s ability to continue performing at its current pace is not assured in the face of an economic downturn. “The nation’s public universities were hit by a 15 percent budget cut last year, after the economy came under pressure from lower oil and commodity prices. University Teknologi MARA, for example, faced a cut of over 23 percent.”

In terms of attracting international students, the final pieces of the puzzle are immigration policy and degree recognition abroad. To address these considerations, Malaysia has recently also sought to streamline once onerous student immigration requirements to include multiple-year student visas [32], and to solicit formal recognition of its institutions by authorities in key sending countries.[13]The Globalization of Tertiary Education and Intra-Asian Student Mobility: Mainland Chinese Student Mobility to Malaysia* Diana Wong and Ooi Pei Wen Universiti Sains Malaysia, Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, Vol. 22, No.1, 2013

That said, the country may stand to benefit from the uncertain U.S. immigration climate facing students from predominantly Islamic countries.

Taiwan

A 13,974 square-mile island, Taiwan is heavily influenced by its relationship with mainland China. On the one hand, China claims Taiwan, which is home to roughly 23 million people, as a province. Taiwan, however, has had a democratically elected government since 1996, and in May 2016, elected Tsai Ing-wen as its first female president. At her inauguration, Tsai Ing-wen pledged to to reduce economic dependence on China. Tensions between mainland China and the new government came to the fore immediately.

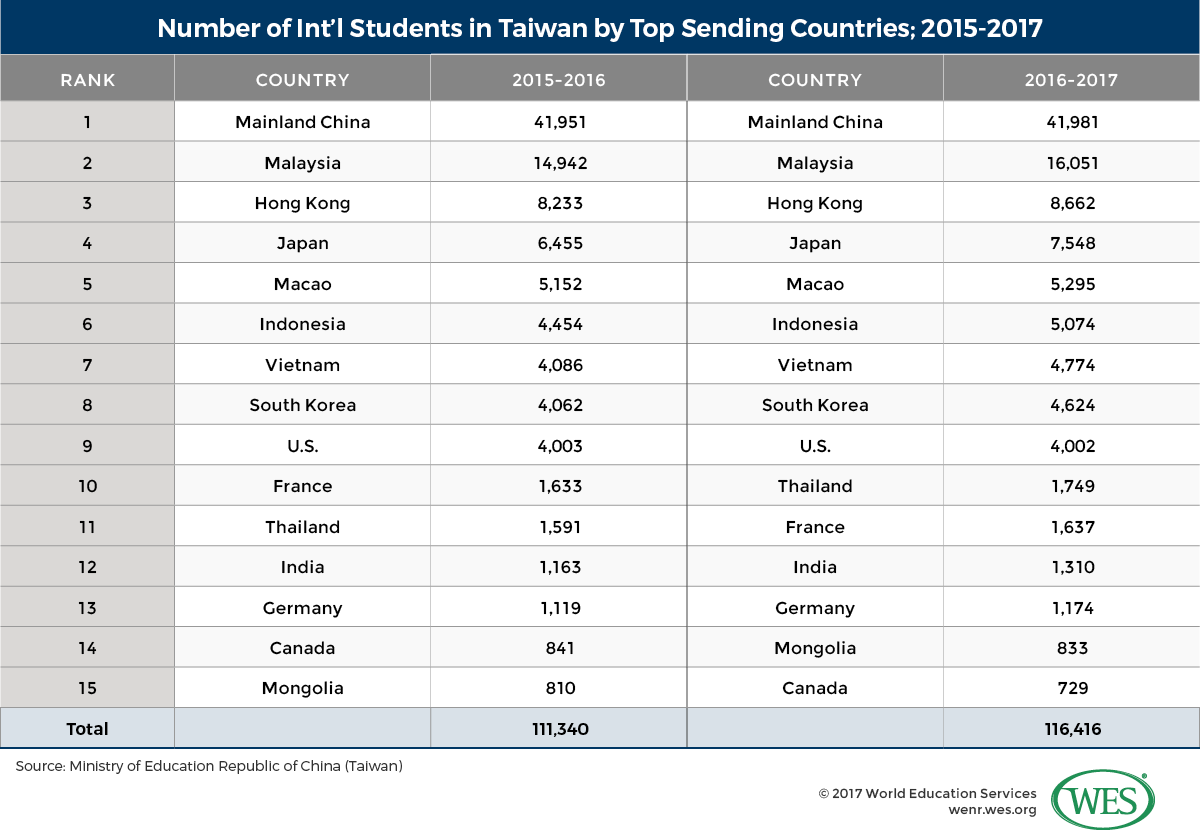

The relationship between the two powers has had an inevitable impact on Taiwan’s ambitions as an education destination. In 2014, former Taiwanese President former President Ma Ying-jeou established a 2020 goal of 150,000 international enrollments in Taiwanese institutions of higher education. The results were rapid: Taiwanese institutions saw an increase of 17.7 percent [33] in foreign student enrollments between 2014 and 2015. As of 2016/17, growth had slowed dramatically – largely in response to changing relations between the new Taiwanese administration and mainland China.

In particular, enrollments from Mainland China have flatlined after years of growth. Under Taiwan’s previous administration, the lifting of a long-standing ban [35] on recruiting Mainland students led to a 140 percent increase in enrollments among Mainland Chinese students compared to between 2010/11 and 2015/16.[14] Data from Ministry of Education Republic of China (Taiwan) As 2016-17, the annual growth rate was 0 percent.

Pull Factors

To compensate, Taiwan’s government has actively sought to reduce reliance on students from Mainland China, and to raise the number of inbound South and Southeast Asian students to 58,000 from the current 28,000 by 2019 [36]. Taiwan has begun to strengthen ties with ASEAN countries and another fast-growing economy, India. In 2016 for instance, the government unveiled its “New Southbound Policy,” which included plans [37] to allocate USD $31.6 million to build a regional talent pipeline within a year, with more than 70 percent of that amount to be directed at attracting students from ASEAN and India. The rationale, according to the Ministry’s deputy minister, is simple. The policy seeks to increase exchanges from countries that are “geographically close to Taiwan and [that] have experienced rapid economic and social development in recent years.” [15]The policy targets 10 Southeast Asian nations, six in South Asia, as well as Australia and New Zealand.

Data indicate that the strategy has had preliminary success: According to the Taipei Times [38], information released by the Ministry of Education show that the number of students from the 18 countries affected by the policy “was 31,531 [in 2016], an increase of nearly 10 percent from 28,741 in the 2015 academic year. Inbound rates from Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand, and India, for instance, all rose in the months since the policy was unveiled.”

The Southbound strategy includes multiple levers to achieve change. Among these are:

- Streamlined visas, residency, health insurance and tax requirements for qualified students from the targeted countries, including the “easing of post-graduation work visa regulations for students from the region will also help to attract and retain skilled graduates” http://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=34667987&Country=Taiwan&topic=Economy&subtopic=Forecast&subsubtopic=Economic+growth [39]

- Subsidies to encourage “ten universities to establish presences in ASEAN with the aim of upping enrolment from the region” http://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=34667987&Country=Taiwan&topic=Economy&subtopic=Forecast&subsubtopic=Economic+growth [39]

- The introduction of Southeast Asian language instruction in Taiwanese elementary schools

- The creation of a database to help match professionals from targeted countries with prospective employers among Taiwanese enterprises operating in Southeast Asia

Taiwan has also had considerable success in attracting students from Northeast Asia. As the Taipei Times [40] noted in April, the numbers of Japanese and South Korean students studying in Taiwan have grown rapidly in a short timeframe. “According to statistics provided by the Ministry of Education, there were 7,548 Japanese students – including degree students, exchange students and other short-term non-degree students – and 4,624 South Korean Students in Taiwan last year,” the Times reported. “Compared to 2015’s figures, the number of Japanese students increased by 19 percent, while the number of South Korean students grew by 21 percent.” One factor in South Korea, said the paper, might be “mounting political tension that made many South Korean students choose Taiwan over China.”

South Korea

Two years ago, South Korea had to recalibrate its foreign enrollment goals. In 2011, the country set a goal of hosting 200,000 students by 2020. By 2015, it was clear that its plans were off track. International enrollments reached 89,537 students in 2011, and then fell for three consecutive years, from 2012 to 2014, when they hit a low of 84,891. So in 2015, South Korea’s pushed the target deadline for 200,000 international enrollments back to 2023. Ever since, international enrollments in degree-granting higher education institutions have risen steadily. Overall growth reached 7.6 percent in 2015 and 14.2 percent in 2016, hitting a total enrollment of 104,262 – a number that includes both degree-seeking students and students enrolled in non-degree programs.

The mix of students enrolled in degree programs in South Korea has shifted as enrollments have risen. Students from across Central, South, and Southeast Asia have begun to arrive in Korea in greater numbers, even as numbers from China have dropped by about 5,300. (Research ties the drop in part to feeling unwelcome welcomed and poorly treated compared to students from other countries.[18]Neo-nationalism: Challenges for international students https://ejournals.bc.edu/ojs/index.php/ihe/article/view/9117/8217)

Despite the fact that the country has slipped its deadline back, it remains highly incentivized to hit its international enrollment goal on schedule in order to offset a looming enrollment deficit. Per the Korean publication Chosun Ilbo [41], Korea’s domestic tertiary-age “student population is expected to dwindle to 470,000 in 2020 and 400,000 in 2023… By 2023 there will be about 110,000 fewer freshmen than there are places” at the nation’s 386 colleges and universities.

Pull Factors

Policy reforms have had a significant role in increased enrollments. According to the Korean press [43], the government planned a number of initiatives to boost inbound enrollments. Among them:

- A proposed ordinance to allow colleges to open departments geared exclusively to international students.

- Government support for English-taught degree courses in sciences and engineering

- Efforts, although modest [44], to open the job market to Korean-educated international graduates

- USD $16 million in 2015 funding to support the efforts of universities and departments outside Seoul to attract international students

- Marketing campaigns and short term programs aimed at recruiting students from other Asian markets

Another factor at play is perceptions of quality. According to the QS World University Rankings, South Korea’s overall reputation has improved by looking at the number of universities in the Top 100. The rankings in 2017 include seven Korean universities are in the Top 200, compared with 6 in 2013, and 4 jumped into the Top 100.

The government has also sought to reshape its university sector to include a greater focus on science and engineering — STEM subjects in high demand among mobile students from across Asia. In 2016, the Korean Ministry of Education launched the PRIME Project (Program for Industrial Needs- Matched Education), to award approximately USD $1.8 billion to 21 universities. To receive the funds, the universities had to open new science and engineering departments, and close or merge existing (primarily liberal or applied arts) departments for the 2017 admission cycle. They also had to limit available seats in non-STEM subjects. “PRIME has had a ripple effect that extends well beyond the 21 named institutions,” noted this publication last year [45]. “Most of South Korea’s non-PRIME universities are planning to adjust admission quotas for students in affected disciplines, adding engineering slots, and reducing seats for students in the humanities, social sciences, and fine arts.” How this will affect international enrollments going forward remains unclear. In the United States, the preponderance of inbound students from top sending countries such as China and India seek STEM degrees, at both the graduate and undergraduate level. However, humanities and social sciences are perceived as a major strength of Korean universities. This point is supported by a survey [46] conducted by the Institute of International Education at Kyung Hee University. Researchers found that 30 percent of international student respondents in South Korea identified culture and arts as among South Korea’s strongest points.

Implications for U.S. HEIs

Asian countries are adopting the approaches that the West used to upgrade the higher education system and scale up international student enrollment. Meanwhile, they are building new models and coping with changing circumstances. For U.S. institutions, it is important to understand the policies and enrollment trends in Asia, so as to take an active position in both competition and cooperation.

Opportunity to gain students from Southeast Asia and South & Central Asia. Overall, the demographics of mobile Asian students are shifting from East to South. Most countries in Southeast, Central, and South Asia have greater need to send out students, which has been demonstrated by the increasing growth rate of outbound students. On the other hand, ASEAN, India, and Pakistan are emerging economies with large youthful populations, and they are highly valued by observers who watch for their development potential and good return on investment in the area of higher education. These countries and regions are witnessing an increase in student mobility within Asia. The U.S. may also have the opportunity to strengthen education links to expand recruitment markets across Asia.

Improve academic excellence with collaborative efforts. The formation of the Asian Universities Alliance presents unique opportunities. Without a doubt, U.S. research-based universities have strong reputation impact around the world. Building closer ties between research-based universities can greater enhance research collaboration and innovative capacity and to jointly improve their international influence in Asia. Partnerships with world-class universities in Asia can develop greater depth and breadth in the way they engage in this region.

References

| ↑1, ↑2 | Estimated based on the data from the UIS Statistics. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies. |

|---|---|

| ↑3 | The mobility of international students and higher education policies in Japan. http://glim-re.glim.gakushuin.ac.jp/bitstream/10959/3710/1/gjis_2_1_19.pdf |

| ↑4 | The Palgrave Handbook of Asia Pacific Higher Education edited by Christopher S. Collins, Molly N.N. Lee, John N. Hawkins, Deane E. Neubauer |

| ↑5 | The ASEAN nations include Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Laos, Singapore, Thailand, Philippines, Vietnam, and Cambodia. |

| ↑6 | http://www.nippon.com/en/features/h00095/ |

| “ [16]Push for foreign students to stay on to work in Japan,” University World News, March 2017 [16] | |

| ↑8, ↑9, ↑13 | The Globalization of Tertiary Education and Intra-Asian Student Mobility: Mainland Chinese Student Mobility to Malaysia* Diana Wong and Ooi Pei Wen Universiti Sains Malaysia, Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, Vol. 22, No.1, 2013 |

| ↑10 | “The shape of global higher education (volume 2): International mobility of students, research and education provision,” British Council, 2017. |

| ↑11 | “ “The shape of global higher education: National Policies Framework for International Engagement,” British Council, 2017. |

| http://dx.doi.org/10.15220/978-92-9189-147-4-en [24] | |

| ↑14 | Data from Ministry of Education Republic of China (Taiwan) |

| ↑15 | The policy targets 10 Southeast Asian nations, six in South Asia, as well as Australia and New Zealand. |

| http://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=34667987&Country=Taiwan&topic=Economy&subtopic=Forecast&subsubtopic=Economic+growth [39] | |

| ↑18 | Neo-nationalism: Challenges for international students https://ejournals.bc.edu/ojs/index.php/ihe/article/view/9117/8217 |