Mini Gu, Advanced Evaluation Specialist, WES

How will outbound mobility among Indian students shift in coming years? The question is top of mind for enrollment managers the world over, especially given the following:

[2]

[2]

- India is the only country that appears poised to come anywhere close to China as a top country of origin for qualified students, and is the number two sender to several top and emerging education destinations, including the U.S., Canada, and Australia.

- Many countries have seen Indian enrollments grow at a fast clip, even as numbers from other top sending countries such as South Korea, China, and Saudi Arabia have either decelerated or dropped.

- India’s demographics and economic growth trajectory mean that it will likely remain a top sender for many years to come.

- Indian student mobility has historically been tied to work potential, and to perceptions of safety, factors which are in flux to varying degrees in key destination countries such as the U.S. [3], Canada [4], and Great Britain [5], thanks to changes in political leadership, shifting immigration policies, and more.

Understanding the ebb and flow of Indian student movement to several key destinations, and the factors that have contributed over the last decade, is critical to predicting what may happen going forward. This article discusses Indian enrollments in several countries, including Canada, the U.K., Australia, China, New Zealand, and Germany, in that context.

The Big Picture

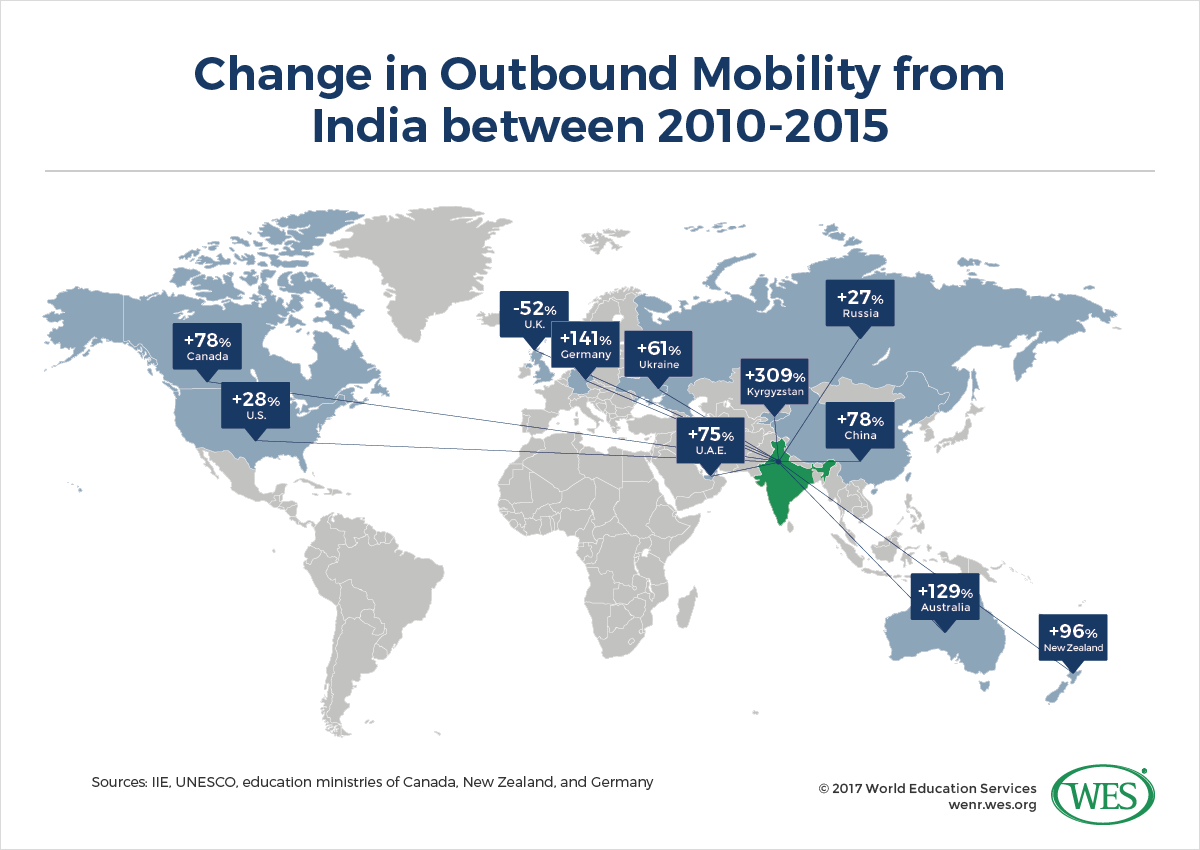

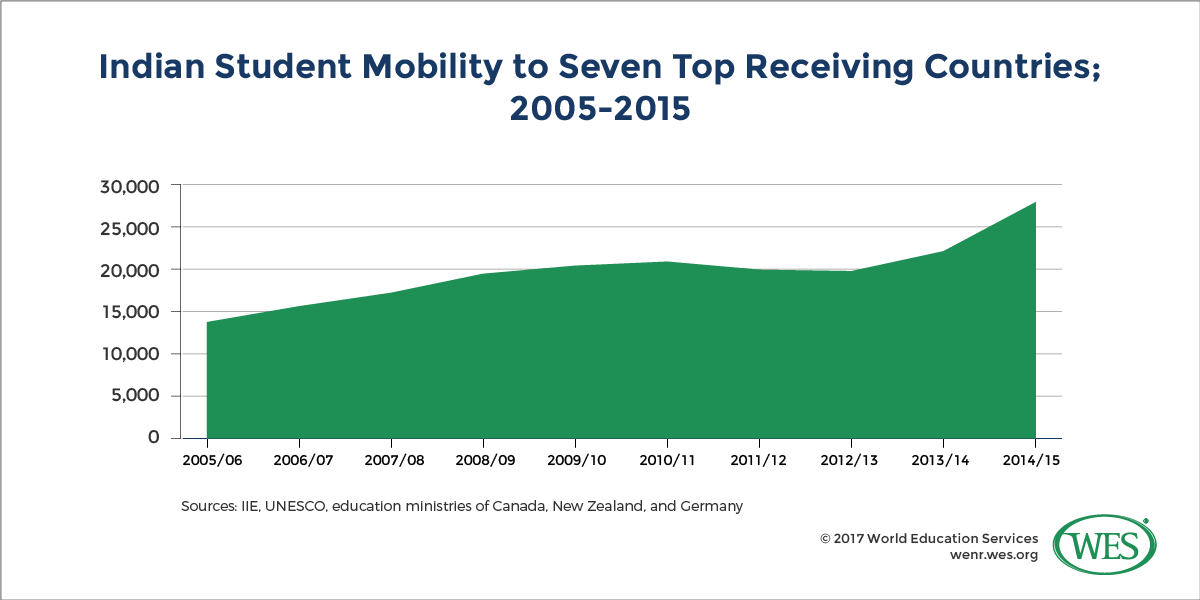

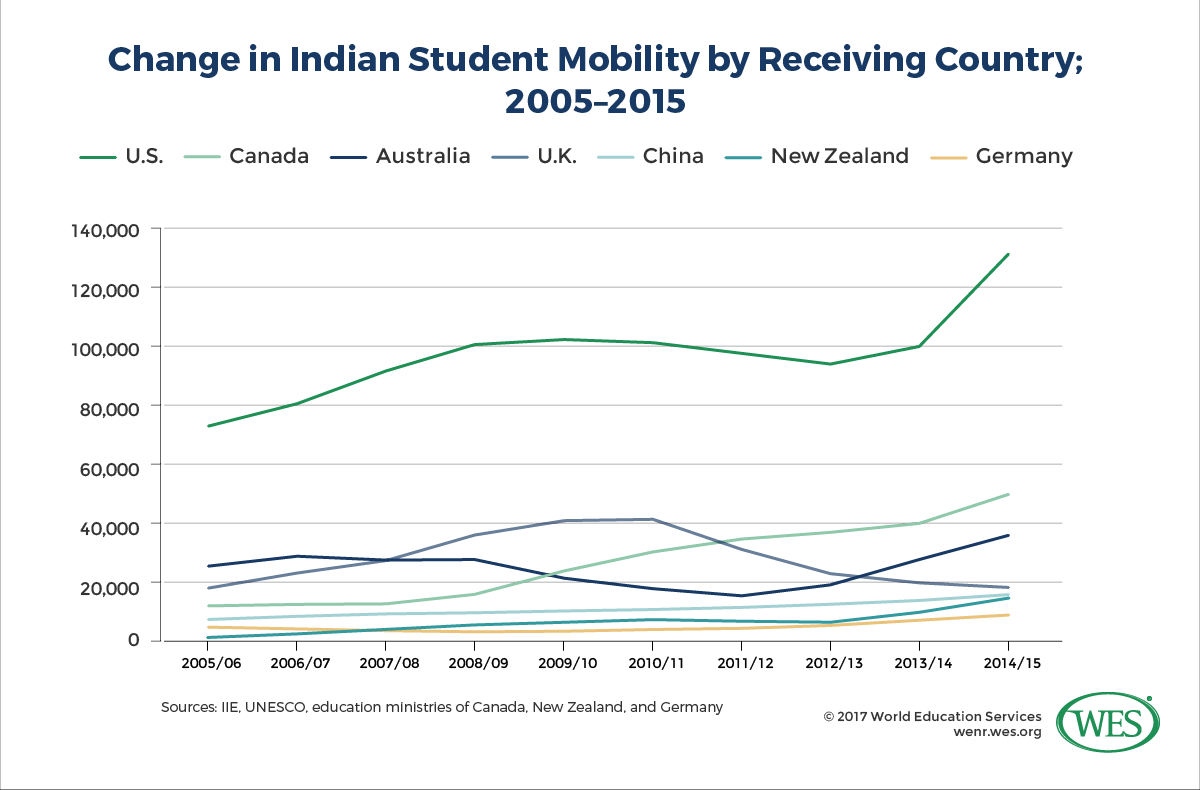

The broad story of outbound mobility from India between 2005/2006 and 2014/2015 is one of growth. According to data from a number of sources, seven top and emerging destination countries – including the United States, Canada, the U.K., Australia, China, New Zealand, and Germany – collectively saw Indian enrollments rise 103 percent, from 138,388 to 281,160.http://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/052642bb-3fd9-4828-b608-c81dff7e539c?_ga=2.258746442.1767971637.1501008235-1779509998.1499982978; [6]New Zealand: New Zealand Ministry of Education https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/indicators/data/student-engagement-participation/3748; [7]Germany: Federal Statistical Office http://www.wissenschaftweltoffen.de/daten/2016/1/2/3 , [2] [8]Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, Project Atlas, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies and organizations.

But within that broad trend, some interesting dynamics are at play. Perhaps most telling are the percentage changes in Indian student enrollments in several top destination countries over the course of a decade. For instance:

- In 2005/06, 138,388 Indian students enrolled in today’s top seven destinations. Among those:

- 55 percent enrolled in the U.S. (76,503)

- 5 percent in Canada (7,456)

- 17 percent Australia (23,849)

- 14 percent in the U.K. (19,228)

- 4 percent enrolled in China (5,634)

- 2 percent enrolled in New Zealand (2,135)

- 3 percent enrolled in Germany (3,583)

- By 2014/15, 281,160 Indian students enrolled in today’s top seven destinations. Among those:

- 47 percent enrolled in the U.S. (132,888)

- 17 percent in Canada (48,633)

- 13 percent Australia (35,380)

- 7 percent in the U.K. (19,485)

- 6 percent enrolled in China (16,694)

- 6 percent enrolled in New Zealand (16,325)

- 4 percent enrolled in Germany (11,655)

Looking at these numbers, clear winners and losers emerge. This article examines the factors at play in six countries, and examines the implications for ongoing enrollment growth in the United States.

Canada: 6.5x Growth, From 7,456 to 48,633 Indian Students in a Decade

Of all emerging destinations, Canada has seen the most sustained long-term upswing in Indian enrollments over the last decade or so. From 2005/2006 to 2014/15, the number of Indian students enrolled rose more than sixfold, from 7,456 to 48,633. Even during the period between 2010 and 2013, when Indian enrollments declined in each of the other six countries under discussion, Canada saw continued growth.

Growth in Indian enrollments in Canada is part of a larger – and ongoing – trend. As noted by The New York Times [11] in May 2017, the country’s overall international student population “surged 92 percent from 2008 to 2015, reaching more than 350,000, according to the Canadian Bureau for International Education.” And although “final figures for this year’s application season are not yet available… early numbers suggest that Canada will be educating many more international students than ever this fall.” The spike is especially notable, say some, among Indian students. Officials at the University of Toronto, for instance, told the Times they had seen a 75 percent increase in enrollments from India in the spring of 2017.

That Canada should have such a strong pull among Indian students is unsurprising. The reasons include:

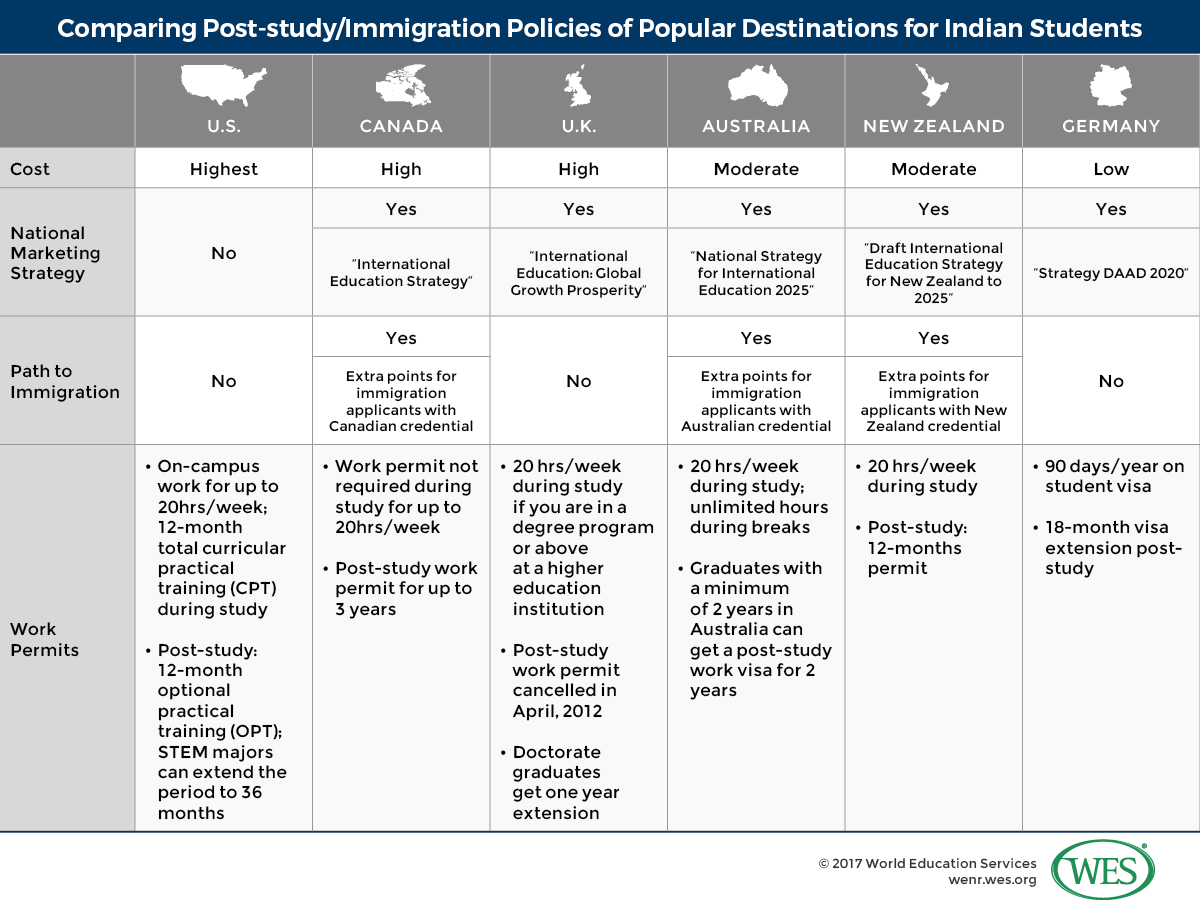

- Safety: Indian students abroad are, as a group, comparatively sensitive to safety related issues. In a May 2017 survey of 165 U.S. colleges and universities [12] by IIE, AACRAO, the Council of Graduate Schools, the National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC), and NAFSA, 80 percent of institutions indicated that “physical safety is the most pronounced concern for Indian students.” Another 31 percent “indicated that feeling unwelcome is also a concern” for Indian applicants. Such concerns are not unique to the United States. “In 2008 and 2009, for example, several Indian students [in Australia] were attacked, and the publicity of these events resulted in a 19 [percent] drop in their enrollments at Australian universities.”[3]Roopa Desai Trilokekar and Zainab Kizilbash “IMAGINE: Canada as a leader in international education. How can Canada benefit from the Australian experience?” Canadian Journal of Higher Education Revue canadienne d’enseignement supérieur Volume 43, No. 2, 2013, page 13 Among Indian students and others, Canada tends to be perceived as ethnically diverse and peaceful, with a reputable higher education system.

- Cost: Education in Canada is a key consideration for outbound Indian students, many of whom have relatively few financial resources to apply toward higher education [13]. For students bound for North America, Canada is less expensive than the U.S. This is primarily for two reasons: the Canadian dollar is weak in comparison to the U.S. (The Times noted that in May 2017, that weakness “[gave] students headed to Canada an instant discount of about 26 percent”) and generally lower tuition fees. India’s November 2016 demonetization policy, which wiped out the value of 86 percent of the currency in circulation in a matter of days [14], likely contributed significantly to Indian students’ interest in Canada as an affordable study destination.

- Immigration policies: Canada’s liberal immigration policies, which seek to attract skilled immigrants, appeal to inbound students as well. For instance, in 2016, the Canadian government announced [15] that it would award candidates who had completed their educations in Canada additional points towards its Express Entry [16]Comprehensive Ranking System [17]. Moreover, the government offers a specialized work permit of up to three years for qualified graduates. The experience can later be applied to applications for permanent resident status.

Australia: 1.5x Growth, From 23,849 to 35,380 Indian Students in a Decade

Australia’s efforts to overcome the perception among Indian students, families, and the Indian government [18] that it is an unsafe study destination – perceptions which led to plummeting enrollments between 2009 and 2013 – appear to have paid off. The country is now the number two destination for outbound Indian students, and enrollments are growing quickly. (The overall number of international student visas rose by 22 percent in the same period.)

The country is also actively seeking to woo Indian students [19] in the face of new-found safety and work-related concerns about study in the United States. As reported by Australia’s Special Broadcasting Service [19], in April, “Education Minister Simon Birmingham [led] a 120-strong education delegation to India… to boost [enrollments] numbers further with many Indian students now shying away from the US – the top choice of Indians for higher education.”

This effort builds on the Australian government’s 2016 release of a 10-year national strategy for international education [20], which articulates a focus on specific target markets, including China and India. Australia has also retooled its immigration and visa policies in order to promote enrollments among Indian and other inbound international students. In 2012 and 2013, for instance, Australia’s federal government implemented a series of revisions to student visa program, including:

- Streamlined visa processing for students applying for bachelor’s programs or higher-level study

- Reduced financial requirements when applying for student visas

- A repeal of automatic and mandatory cancellation provisions for student visas

- Access to two-year post-study work visa for all students holding Australian bachelor’s degrees

From the Indian student perspective, one factor that may weigh against Australia is cost. Tuition in Australian institutions is comparatively expensive (almost on par with tuition in the U.K. and U.S., according to one source [21]). However, expense may be offset by the fact that international students are legally permitted to work up to 20 hours a week, as well as by Australia’s relative proximity to the Indian market.

The United Kingdom: A Roller Coaster: From 19,228 to 39,090 to 19,485 Indian Students in a Decade

The story of Indian student enrollments in the United Kingdom stands in stark contrast to that of the other countries under discussion. It also serves as a cautionary tale for other nations that have an overreliance any one or two sending countries. Of particular note for observers in the United States is the impact that immigration policies and an anti-immigrant sentiment have had in squelching what once looked like unstoppable growth in Indian enrollments.

Per the online publication Quartz [23], data from “the Higher Education Statistics Agency, which collects statistics on public-funded British higher education, shows that the number of Indian students who enrolled there declined from 39,090 in 2010-11 to 18,320 in 2014-15. That’s a fall of 53.1 percent.” The steep fall in the U.K. is considered a direct response to anti-immigrant sentiment, in particular restrictive immigration policies introduced in 2012, when a new visa policy [24]shortened the time limit for non-EU graduates to secure a job and a competitive minimum salary to be eligible to stay in the country.

Despite the high cost and tightening visa controls, Indian enrollments in the U.K. are unlikely to dip below a certain level for several reasons:

- International recognition of the high quality of higher education in the U.K. Even though it is tough for students to stay beyond their study, degrees from U.K. institutions are believed to open more doors to employment in their home countries as well as around the world.

- Post-colonial and linguistic influences. Particularly among Indian youth in a position to study abroad, English is the dominant mode of instruction through secondary school. Given that the Indian higher education system is primarily modeled on the British system, and that the U.K. has a long-standing tradition of enrolling Indian nationals in higher education, there is a strong likelihood that at least some portion of Indian students will continue to favor British institutions over options in other countries.

In 2016, the country unveiled an India-based recruitment campaigned and scholarship program aimed at reinvigorating Indian interest and enrollments in U.K. institutions. In late 2016, the numbers rebounded somewhat. As noted by Universities U.K [25]., “On the first of December [2017] the U.K. Home Office released data on the student visas issued between July and September this year. Figures [showed a 6 percent] increase in the number of Indian students receiving visas, compared to the same period last year.” This rise broke a downward slide that had been ongoing since 2010.

New Zealand: 7.6x Growth, From 2,135 to 16,325 Indian Students in a Decade

New Zealand is the only market which had a higher growth rate of inbound students than the U.S. last year. Of more than 125,000 total international students in 2015, 23 percent were from India. The number represents a 150 percent jump from 2010, and almost eightfold growth since 2005/06. India ranks second to China as a country of origin for these students.

Indian students seeking pathways to employment and residency are also driven by the ease of obtaining student visas and its post-study work opportunities. New Zealand’s Pathway Student Visa [26] introduced in 2015 is valid for up to three consecutive programs of study for up to five years. It provides more mobility to international students when they transfer between different levels or types of programs. In many cases, New Zealand is not most students’ top-ranked destination. However the transportability of New Zealand academic credential to other British and commonwealth education systems has positioned it as a leading backup choice. Other pull factors such as safety and the relatively low cost of tuition compared to other English-speaking destinations may become increasingly attractive given current political tensions in more traditional top-choice destinations such as the U.S., or the U.K.

The rapid surge of international students in New Zealand, particularly those from India, has, in recent years, led to substantial growing pains. Most related to minimum language requirements, unscrupulous recruitment practices and agents, fraudulent applications, and labor exploitation. In order to support the government’s objectives for international education, the country has actively sought to redress issues.

In 2016, for instance, New Zealand’s government implemented new regulations governing the “pastoral care of international students” by requiring affected providers “to take all reasonable steps to protect international students; and…[by] ensuring, so far as is possible, that international students have in New Zealand a positive experience that supports their educational achievement.” Specific requirements address: fair and honest marketing abroad; management and monitoring of contracted educational agents; efforts to ensure admitted students are eligible for student visas; adequate on-campus orientation; student safety and well-being; international student support services; protocols for addressing student grievances; and more.

In June 2017, the government released the International Student Wellbeing Strategy [27] which seeks “to improve foreign students’ experience while studying in New Zealand, and to increase international enrollments. As noted by Study Travel magazine, the new policy sets the expectation that international students should “be able to support themselves and have accurate information about the costs of living and studying: understand their rights to work; understand pathways to employment and residency; know their rights in relation to accommodation and dispute resolution; and have access to financial advice.”

In face of recent turmoil, the growth in enrollments from India may soften, but the effect is likely to be relatively short term.

Germany: 3.3x Growth, From 3,583 to 11,655 Indian Students

Of particular note is a recent uptick in Indian enrollments on German campuses. The country recently “overtook Russia as the second highest source country, with 11,655 students,” the PIE News [28] reported in August 2016. Growth has continued since. Most recently, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) reported that 16.1 percent more students from India [29] came to Germany in the winter semester 2015/16 compared with the previous year (13,537.)

This draw is attributable to a few key factors:

- Reputation: Germany has a strong reputation internationally [28], both for high quality scientific research and for higher education more generally. High quality in the STEM fields is likely a particularly strong draw among the 83 percent of Indian students in Germany who pursue degrees in STEM fields. (This margin is comparable to the 80.1 percent of STEM enrollments among Indian students pursuing degrees in the U.S.) Germany’s Excellence Initiative [30], begun in 2007, has likely contributed to this appeal.

- Language: As of 2017, Germany had reportedly increased the number of master’s programs taught in English by 13 percent since 2011, to a total of 733 a likely draw for many Indian students, given both their own educational backgrounds, and the importance of English in scientific publishing and global academia.https://openjournals.library.usyd.edu.au/index.php/IEJ/article/view/10312 [31].

- Cost: Germany provides free tuition for foreign students, a particular draw for international students from India. As noted in this publication in 2015, WES research shows that “Indian students [tend to] seek ‘value for money’ and are highly dependent on bank loans or financial support from universities.”

- Employment: The same WENR article, authored by Rahul Choudada, notes that these students “also tend to enroll in fields of study that have good employment potential. For example, many … begin their studies in the U.S. with the goal of working in the information technology (IT) services sector. They start by enrolling in master’s level programs in STEM-related fields [32], follow it with a 29-month Optional Practical Training (OPT) experience in the IT industry and finally seek H1-visas for employment.” Germany offers similar benefits, allowing international students to extend their visas for an 18-month period after studies in order to find employment.

It’s unclear whether this trend will continue at its current accelerated pace, but at least some observers are bullish. “Based on the past 3 years’ momentum, and the smart initiatives being rolled out to attract students, we are projecting that Germany will overtake [the U.K.] and become the international education leader in Europe in the next five years,” wrote Maria Mathai of India-based M.M Advisory Services, in the company’s 2016 “Indian Students Mobility Report.”

China: 3x Growth, From 5,634 to 16,694 Indian Students in a Decade

The internationalization of higher education is part of China’s National Plan for Medium- and Long-term Education Reform and Development [33]. On the basis of the general guideline, the Ministry of Education published the ambitious Study in China Plan [34] whose goal is to become the largest study abroad destination in Asia, and to enroll 500,000 foreign students in primary, secondary and tertiary education institutions by 2020.

The target for higher education alone is 150,000.

Measures to attract foreign students abound:

- The intensified collaboration among ASEAN countries and the “One Belt and One Road” (OBOR) initiative is expected to raise the scale of two-way student exchange. Figures [35] from 2016 show that the growth rate of incoming students from the 64 OBOR countries is 13.6 percent, reaching 207,746.

- Increasing government scholarships. Ministry of Education statistics show that 40,600 scholarships have been granted in 2014, almost 500 percent growth from 2006 (8,500.) The OBOR seeks to provide at least 3,000 scholarships per year for new students.

- Expansion of joint degree programs established under the framework of Sino-foreign cooperation of running schools [36] is likely to drive more inbound mobility for short-term study. Currently there are over 2,500 approved joint programs and institutes. The engagement of high-profile foreign partners – such as New York University, Duke University, and University of Nottingham – will bring in more interest from foreign institutions and students alike. Chinese institutions have also been reaching out to 14 countries and regions, mostly along the area of OBOR, such as Suzhou University in Laos and Xiamen University, Malaysia.

Interestingly, China’s unique appeal to Indian students is its inexpensive medical education. Over 80 percent of Indian students out of a total 13,578 in China are enrolled in an MBBS program [37].

Proximity and cost are likely additional factors in Indian student mobility to China, as indicated by the fact that Indian students are also enrolling in increased numbers in institutions in Russia, Nepal, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Considerations for the U.S.

As a study abroad destination, the U.S. is unparalleled, thanks largely to the sheer size of its education system. Nonetheless, the other emerging destinations have their own strengths, which might eventually yield significant alterations in student mobility patterns. In particular:

- Most of the countries under discussion are guided by national strategies to develop the international education sector and, in the current political climate, are likely perceived by students as more welcoming than the United States. From the downward trend in the once-dominant U.K., it is clear that perception matters, and it remains hard to predict whether measures such as scholarship schemes [38] will offset the impact.

- In terms of Canada, Australia and New Zealand, clear study to immigration pathways are a plus for Indian students.

- Costwise, most countries other than the U.K., and possibly Australia, are more affordable than the United States. Especially as more and more English-taught programs become available in these destinations, students may increasingly see them as a viable option.

References

| http://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/052642bb-3fd9-4828-b608-c81dff7e539c?_ga=2.258746442.1767971637.1501008235-1779509998.1499982978; [6]New Zealand: New Zealand Ministry of Education https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/indicators/data/student-engagement-participation/3748; [7]Germany: Federal Statistical Office http://www.wissenschaftweltoffen.de/daten/2016/1/2/3 | |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, Project Atlas, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies and organizations. |

| ↑3 | Roopa Desai Trilokekar and Zainab Kizilbash “IMAGINE: Canada as a leader in international education. How can Canada benefit from the Australian experience?” Canadian Journal of Higher Education Revue canadienne d’enseignement supérieur Volume 43, No. 2, 2013, page 13 |

| https://openjournals.library.usyd.edu.au/index.php/IEJ/article/view/10312 [31]. |