Hanna Park, Senior Training Manager, WES

In terms of student recruitment, is Vietnam a worthwhile next investment? Most likely, yes. Consider:

- The United States is, depending on who is reporting, either the number one, two or three destination for outbound students from Vietnam.[1]Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies.

- Vietnam has a growing GDP, and rapidly expanding middle and upper class. The number of middle-class Vietnamese will almost triple (to 44 million) by 2020 and reach 95 million by 2030. It is also home to an increasing population of “super rich.”

- In 2016, Vietnam was the top Southeast Asian sender of students to the United States by a wide margin.Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) [1] reports are even higher, indicating that more than 30,000 Vietnamese had received student visas in recent months. In recent months, Vietnam surged past Canada to become the fifth leading sender of students to U.S. campuses.

- Vietnam is the 11th leading sender of students to Canada; and Canada is the 10th most popular education destination for students from Vietnam. Numbers are up 57 percent since 2011.

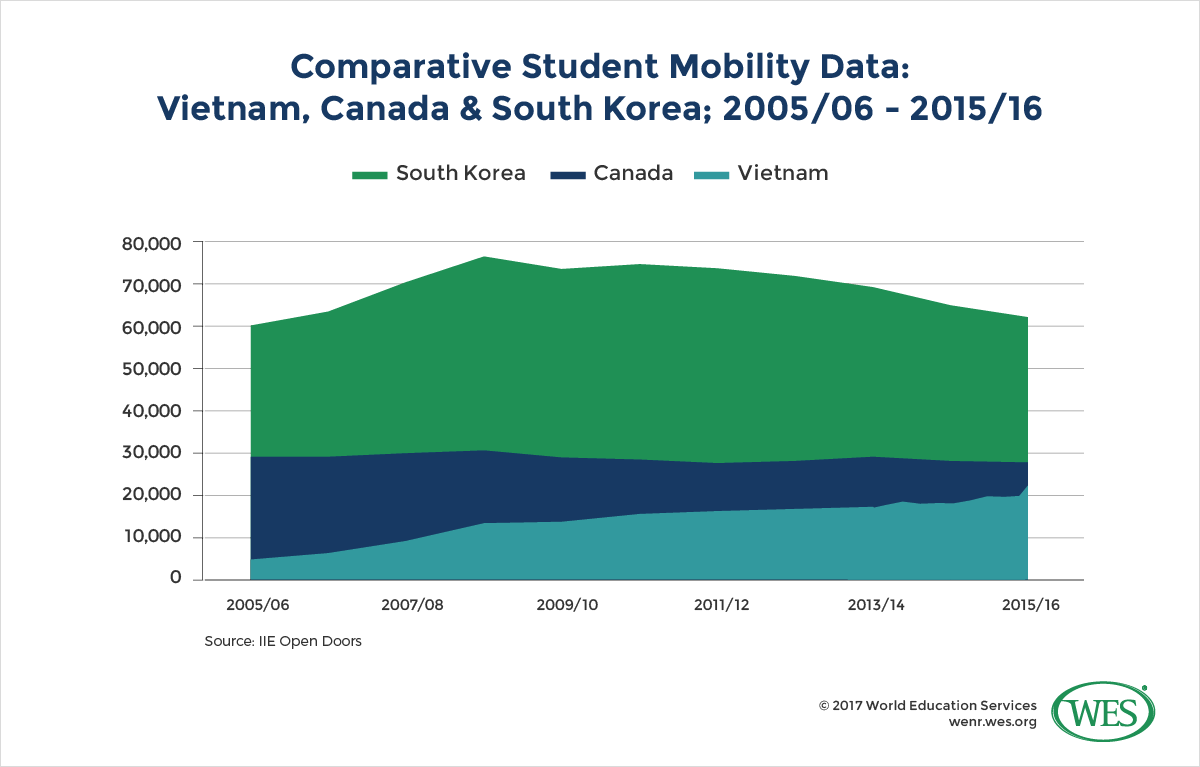

Comparative Student Mobility Data for Three Countries, 2005/06 – 2015/16

The number of U.S. bound students from Vietnam, has seen a steady rise since 2005/06. By contrast, the number of students South Korea has sent to the U.S. has diminished since 2005/06, while mobility rates from Canada have remained flat. (NOTE: According to the latest data from SEVIS, the number of visas issue to Vietnamese students surpassed the number issued to Canadian students in 2017.)

World Education Services has long advocated Vietnam as a viable recruitment market for institutions in North America [3]. Understanding these students’ culture and family backgrounds, as well as the contextual factors that can ‘push’ them from Vietnam and ‘pull’ them toward institutions in other countries, can go a long way toward helping institutions develop an actionable plan for reaching out to and them.

Characteristics of Vietnamese Students Abroad

Cultural Mores

According to SEVIS data from May 2017, the highest numbers of Vietnamese students in the U.S. were in California and Texas. The popularity of these destinations, which are home to the United States’ largest Vietnamese immigrant populations in the U.S., reflects what we know about Vietnamese culture: Family and kinship are still strong values in Vietnamese society [4], which has its roots in Confucian traditions. Elders and parents [5] tend to be respected by younger generations for their experience and knowledge. On the flip side, children’s educational successes — including achievement of higher degrees – are considered an achievement of the whole family. Such cultural influences play a critical role in determining student journeys in education.

Economic Determinants

Economic considerations are also a factor. About 90 percent of Vietnamese students are self-funded [6]. World Bank data shows that Vietnam had a GDP per capita of $2,185.7 in 2016 [7], a 5.1 increase over the previous year – the continuation of a long-term growth trend. The country’s consumer class is growing in tandem. As the Nikkei Asian Review [8] reported in late 2016:

“… what Boston Consulting Group says is Southeast Asia’s fastest-growing middle class. According to BCG, [Vietnam’s] ‘middle and affluent class’ … will double to 33 million people, about a third of the population, between 2014 and 2020. Marketing researcher Nielsen estimates that the number of middle-class Vietnamese will reach 44 million by 2020 and 95 million by 2030.

Moreover, Vietnam’s “ultra-rich population [9]” is reportedly “growing faster than any economy in the world.”

Still, for most Vietnamese, an education in the United States or Canada remains comparatively expensive. This fact likely accounts for the attendance patterns in the U.S. In particular, Vietnam is the second leading country of origin for the 95,376 international students enrolled in U.S. community colleges (behind China.) Almost one out of every 10 of those students is Vietnamese [10]; for many, community colleges are an affordable and common on-ramp to longer term study. [11]

Selection Criteria: Why This School?

In a 2015 paper [12], researchers Mai Thi Ngoc Dao and Anthony Thorpe reported that Vietnamese students select schools based on a range of factors, including program, price, and word of mouth. Interestingly, offline information sources ranked higher in influence than online sources among the 1,124 students they surveyed for their report – a clear indicator that in-person recruitment efforts, whether via known agents or school staff, may be a necessity for institutions interested in increasing their Vietnamese student population.

Dao and Thorpe note that recruitment efforts should be specific to students’ academic levels.

- Undergraduate recruitment, for instance, should be focused on institutional advertising that targets family influencers – mainly parents and siblings. This strategy ties back to Vietnam’s culture of strong family ties, where parents’ opinion is a main deciding factor in selecting institutions.

- At the graduate level, universities should focus on highlighting programs, flexible tuition payment schedules and methods. They should focus on influencers outside the family: teachers, friends, and colleagues.

Level and Fields of Study

All in all, IIE data indicate that more than two-thirds of U.S.-enrolled Vietnamese students are undergraduates [13] (including those at community colleges.) About 15 percent are enrolled in graduate work, 8 percent in optional practical training, and 10 percent in non-degree programs.

Business, in general, is Vietnamese students’ most common field of study, both domestically and internationally. According to IIE’s most recent data, for instance, 30 percent of Vietnamese students in the U.S. are in Business/Management, making it by far the single largest field of study for this population.

New Destinations: Japan

While UNESCO’s statistics [14] on tertiary student flows show that the U.S. is the most popular destination for study abroad, ahead of Australia and Japan, other sources put Japan at the top of the top-three heap, and Australia in third place.

Although the U.S. higher education “brand” remains coveted, and English language skills are highly valued [15], Japan is an increasingly popular destination among Vietnamese students destination. The Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO) [16], reported 54,000 students from Vietnam in its most recent report, a “more than 12-fold [increase] in the six years” since 2010 according to Bloomberg [17]. Proximity is one factor. Moreover, Japan has begun to invest in Southeast Asian countries [18] as part of an effort to grow its economy, launching efforts to actively recruit of foreign students across the region, with an intensive focus on Vietnam. In this context, Vietnamese students and families view education in Japan as a route to employment either back home or abroad.

NOTE: Vietnamese student pathways in Japan do not necessarily follow a conventional academic track. The majority of Vietnamese students start their educational journey at Japanese Language School. Because most of them are self-funded, many also seek opportunities to work part-time to alleviate the financial burden. At the end of completing the language curriculum, more than half of the students enroll in vocational schools while a small percentage continue to universities.

Changes at Home: Quality and Reform; Push and Pull

A lack of quality at home has long been cited as a big push factor for Vietnamese students to leave home, just as the quality of U.S. institutions and the perceived value of U.S. degrees are major “pulls” toward the States.

Of particular note on this front are employment trends in Vietnam: In the last three months of 2015, a rising number of Vietnamese bachelor and master’s degree holders were unemployed [19], despite overall labor market improvements. Observers faulted decades of “breakneck massification” and the resultant the low quality of higher education as key factors. In the face of this and other challenges, Vietnam’s national assembly elected a new Minister of Education and Training [20] in early 2016. The new education minister, Phung Xuan Nha was expected to focus heavily on internationalization as one key to improving quality at the tertiary level. Under Nha, the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) has established quality improvement in higher education as a top priority and embarked on an ambitious reform agenda:

- In 2016, it established a National Qualifications Framework [21]. At that time, Vietnamese universities also began offering courses in English [22], as part of an effort to set the stage for joint training programs, and to encourage the development of training institutes by foreign investors and universities.

- A draft decree seeks to establish the minimum investment capital required for foreign investors to set up universities in Vietnam at about USD $45 million. The new requirements also mandate that all lecturers at foreign-owned universities have at least a master’s degree, with around half of them holding a doctorate (an increase from 35 percent under previous legislation).

- A second draft decree removes enrollment caps at the primary and secondary levels at schools back by foreign investments, opening up access to more local students.

Recruitment Prospects for the U.S. and Canada

If successful, Vietnamese efforts to improve the quality of its higher education system may, over the long term, lead to diminished student interest in the West as a higher education destination.

In the short term, different factors will be at play. Of particular note is increased mobility in Asia itself, both to Japan (as noted above) and to other rising regional destinations like South Korea, Thailand, and Malaysia.deregulate Vietnamese education agents [23]. The action is likely to markedly increasing outbound student applications and numbers, while also putting the onus on receiving institutions to, as Vietnam education consultant Mark Ashwill noted “choose [agents] carefully, hold [them] accountable, monitor their activities, and reward them for a job well done, which is to help recruit qualified and suitable students.”

The United States’ International Trade Administration’s Top Education Markets report for 2016 [24] offers a generally positive outlook on recruitment prospects in Vietnam. “Upward growth [has] given little sign of moderating, offering important … opportunities for U.S. colleges and universities.” The same holds true for Canada, where the country’s International Education Strategy, unveiled in 2014, identified Vietnam as a priority recruitment market. The Canadian government reports [25] that, “in 2015, Canada hosted close to 5,000 students from Vietnam (for six months or more), an increase of 57 percent from 2011, making Vietnam Canada’s 11th largest source country for international students in Canada.”

References

| ↑1 | Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ashwill, Mark. NAFSA presentation; “Keys to Successful Non-Commission-Based Recruitment in Vietnam,” June 2, 1017. |

| Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) [1] reports are even higher, indicating that more than 30,000 Vietnamese had received student visas in recent months. In recent months, Vietnam surged past Canada to become the fifth leading sender of students to U.S. campuses. | |

| ↑4 | Per data from UNESCO’s UIS report on the Global Flow of Tertiary- Level Students |