Mingyue Chen, Credential Examiner, with WES Staff

This education profile describes Canada’s education system, and trends in inbound and outbound international student mobility. It includes sample educational documents, and discusses credential evaluation challenges specific to the Canadian system.

Canada, the northernmost country in the Americas, is characterized by a combination of sparsely populated provinces and territories, a handful of large vibrant cities, and an active embrace of large-scale immigration. The country, which shares the longest international border in the world with the United States, is bilingual, with French and English both recognized as official languages. It is second in size only to the Russian Federation. Canada has the world’s third largest oil reserves, a high standard of living, and a colonial history. Its economy began to see modest growth in 2014, after a slow recovery from the global economic recession that began in 2008.

Among all the countries in the Western hemisphere, Canada is particularly notable for its pro-immigration stance, which seeks to address two key challenges: labor shortages among highly skilled workers and an aging populace. A recent report by the Conference Board of Canada estimated that Canada needs to increase immigration rates to 408,000 annually until 2030 in order to ensure future economic growth and fiscal stability in the face of accelerated population aging. The inflow of immigrants is the primary factor driving an anticipated population increase from 36.3 million people in 2016 [3] to a projected 51 million people in 2063, according to recent medium-growth predictions [4] by the Canadian government.

To ensure that the country receives those who can contribute to the economy and skilled labor market, Canada actively seeks out skilled immigrants, employing a points-based immigration system that prioritizes entrants based on educational attainment, prior work experience, language skills, and age.

Canada’s embrace of immigrants contributes to its growing reputation as an international education destination. In 2016, the country ranked as the seventh most popular study destination for international students in the world, according to the Institute of International Education’s (IIE) Project Atlas [5]. Many analysts expect that Canada’s importance as an international study destination will increase significantly [6] in 2018 and beyond, particularly in light of political changes that have diminished the appeal of other countries, most prominently the U.S. and U.K., which have traditionally been leading English-language higher education destinations. And despite a history of policies that sometimes encourage and sometimes discourage international enrollments, the country has, most recently, implemented policies that ease pathways [7] to permanent residency for international students.

International Student Mobility

Inbound Mobility

The number of international students studying in Canada grew by 92 percent between 2008 and 2015, from 184,155 to 353,000 students, according to the Canadian Bureau for International Education [8] (CBIE).reports [9] suggest that, in 2015, an additional 90,000 international students pursued short-term language studies in Canada. The growth is driven by enrollments from China and India, which, between 2006 and 2015, increased by 182 percent and 513 percent, respectively.http://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/052642bb-3fd9-4828-b608-c81dff7e539c?_ga=1.129598988.1449264574.1482960422 [10]. Enrollments by Nigerians have seen exceptional increases in recent years, growing by 25 percent [11] between 2013 and 2014 alone.

In 2018, enrollment numbers are expected to spike even further. The University of Alberta, for instance, reported an 82 percent increase [12] in international graduate applications in 2017, and a 27 percent increase in international undergraduates’ acceptance of admissions offers. International student acceptances of admissions at the University of Toronto were up by 22 percent in the same time frame.

An overwhelming number of international students tend to go to just a few destinations. In 2015, for instance, fully 86 percent were enrolled in universities in the provinces of Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec.lowest [13] among the big four English-speaking destination countries (U.S., U.K., Australia, Canada), making it a top draw for students from around the world, including the United States. According to the Globe and Mail [14] newspaper, currency exchange rates in January 2016 meant that U.S. “undergrads paying with U.S. dollars … pay, on average, about $15,000” a year in tuition in Canada. In the U.S., by comparison, “the average tuition cost for one academic year at a public college was …. $23,893 for out-of-state students.”Statistics Canada [15]. Despite this cost advantage, enrollments of U.S. degree students at Canadian universities have remained relatively constant in recent years. They stood at 8,049 in 2013, according to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics [16] (UIS), and have changed only marginally over time. Many universities in Canada reportedly [17] experienced a 20 – 80 percent growth in student applications from the U.S. for the 2017- 2018 academic year. Speculation that U.S. applications will spike in the future remain unproven.

In recent years, the United States has not even ranked among the top-five senders of international students [8] to Canada, reaching number 5 only in 2015, when the other top senders included China (34 percent), India (14 percent), France (6 percent), and South Korea (6 percent). The next three were Saudi Arabia, the U.S., and Nigeria, each of which supplied about 3 percent of Canada’s total international enrollments.for 39 percent of enrollments in 2013-2014, [18] with France being the biggest sending country, according to the Canadian government.

Why They Come

Immigration is dramatically reshaping Canadian cities, particularly in immigration hubs like Toronto, Montréal, and Vancouver, which also attract far and away the greatest numbers of international students in Canada. In fact, if current immigration levels hold steady, government estimates predict [19] that immigrants’ share of the country’s population could swell from 20.7 percent in 2011 to 30 percent in 2036. By that point, almost one in two people in Canada may be either the child of an immigrant or a first generation immigrant.

These demographic changes are a draw for international students. A survey by the Canadian Bureau for International Education [11] (CBIE) found that educational quality, Canada’s multicultural society, and perceptions of safety topped students’ list of reasons for enrolling in Canadian institutions.

A clear path to residency and citizenship is another draw. In 2016, the Canadian government made two moves that could increase the nation’s appeal among international students. First, it revised its Express Entry visa program to make it easier for international students to apply for permanent residence. International students will now receive points for academic credentials earned in Canada. The change is expected to increase the percentage of international students among those invited to apply for residency under Express Entry from 30 to 40 percent [20]. The Canadian government also introduced legislation that would ease citizenship requirements [21] for international students.

Both of these policy changes are in line with Canada’s 2014 international education strategy [22], which positions international students as a source of skilled labor that can help to compensate for an aging labor force.

Outbound Mobility

Compared to their counterparts from other countries, Canadian students are relatively reluctant to study abroad [23]. Outbound student numbers have remained flat in past years, holding constant at about 49,770 degree students in both 2015 and 2016 (UIS). Only about 2 percent of Canadian students studied in degree programs abroad in 2016, more than half of them in the adjacent United States (UIS [24]).

One of the biggest mobility barriers for Canadian students, and the main barrier cited by 80 percent [25] of 7,000 students surveyed by CBIE in 2016, is cost. To help address this problem, a number of governmental scholarship programs have been initiated at federal and provincial levels. In 2014, the federal government, for example, launched the “Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Scholarship [26],” funding the exchange of 1,500 students from Commonwealth countries with $40 million CAD over five years, an amount that was subsequently increased by another $10 million CAD [27]. Critics contend, however, that current funding levels are insufficient to boost outbound mobility. The CBIE, which runs its own international scholarship programs, has called for funding increases in order to drastically boost Canada’s outbound mobility rate to 15 percent of post-secondary students by 2022 [28].

According to the Institute of International Education (IIE) [29], 26,973 Canadians were enrolled at U.S. institutions in 2015-2016, making Canada the fifth largest contributor of international students in the country. Other popular study destinations included the U.K. (6,309 students), Australia (3,430 students), and France (1,377 students) (UIS [24]). When studying abroad, Canadian students enroll most frequently in business (21 percent), engineering (14 percent), social sciences (12 percent), health science (10 percent) and education (6 percent).

Geographic proximity is likely one reason the U.S. is the preferred destination for Canadian students – a speculation given credence by the fact that a majority of Canadians enroll at U.S. institutions in northern border states [30] (with the exception of California). Another factor driving mobility to the U.S. is the competitive [30] admissions process at high-demand Canadian universities. The U.S. also offers Canadian students a wider range of study options, such as liberal arts colleges, which are less common in Canada.

Transnational Education

Canadian providers operate 186 mostly English-language elementary and secondary schools abroad, according to a 2014 report [11] by CBIE , including at least 134 officially recognized Canadian curriculum schools [31], some of which offer pathway programs in collaboration with Canadian universities.[6]These programs present challenges for credential evaluators. Tips on addressing tem are addressed at the end of this article.

Canadian universities also pursue a large variety of internationalization activities, including joint and dual degree programs, increasingly focused on China, as well as distance education. According to a comprehensive 2014 survey [32] by the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, 78 percent of surveyed Canadian universities offered dual, double, or joint degree programs in collaboration with foreign partner institutions – a drastic increase from 48 percent in 2006. Distance education programs, meanwhile, are widely offered [11] for both domestic and international students.

Canada is not a leading country when it comes to transnational branch campuses at the post-secondary level. The C-Bert directory [33] on international branch campuses, for example, currently only lists six active Canadian-owned branch campuses abroad (in China, Japan, Qatar and Saudi Arabia), whereas U.S. institutions maintain 77 such campuses. Foreign campuses located in Canada, likewise, are limited to six U.S.-owned campuses.

In Brief: The Education System of Canada

Statistics and Administration

In 2010- 2011, the combined total of elementary and secondary students enrolled in Canada’s public schools was 4,708,548. [34] This number represents a decrease of 7 percent from 2001, and is tied to an overall drop in birthrates. Ontario and Quebec, Canada’s largest provinces, accounted for more than 60 percent of all school enrollments. Enrollments at the upper-secondary level stood at 1.53 million in 2013 (UIS). Some 90 percent [35] of Canadian adults aged 25 to 64 had at least completed high school in 2015, significantly more than the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) average of 78 percent.

Because Canada has no centralized ministry of education, it’s system of education is relatively complex. Each of the country’s ten provinces and three territories govern their education systems autonomously, unders separate jusrisdictional authority.delegated the governance [36] of education to the territorial governments. Despite commonalities and articulation agreements among and between the various jurisdictions, the differences in policies that govern curriculum, assessment, and accountability are considerable, as will be discussed below.

To harmonize the system, a joint Council of Ministers of Education [37] acts as an intragovernmental body that facilitates coordination of education policies among the provinces. The Council also represents the multiple jurisdictions at both national and international forums.

Languages of Instruction

Canada has two official national languages: English and French. Outside of Quebec, English is the dominant language of instruction in all provinces and territories. In Quebec, a large province of 8.2 million people, French is the dominant language of instruction. However, French-speaking minorities exist in other provinces, while English-speaking minorities live in Quebec. Wherever the population size warrants it, education in the non-dominant official language is available at publicly funded schools. For example:

- French-language schooling is provided in parts of the Anglophone province of Manitoba.

- English-language schooling is available in the Francophone province of Quebec, even though certain conditions [38] such as previous enrollment in an Anglophone school or Anglophone parentage, must be met before pupils are allowed to enroll.

Pupils who do not meet these criteria can attend so-called immersion programs, which exist in both Anglophone and Francophone provinces. A pupil in a French immersion program in British Columbia, for example, will be taught entirely in French from kindergarten. French is then slowly phased out and replaced by English as the main language of instruction during the final years of secondary school, with the aim of fostering bilingualism.

In addition to English and French, elementary education is offered in Aboriginal languages throughout the country at institutions governed by First Nations, Inuit, and Métis school boards. The Kativik School Board in the Nunavik region, for example, provides instruction in Inuktitut, French, and English [39]. On Prince Edward Island, some First Nations children are taught in both Mi’kmaq and English until they reach seventh grade [40], at which point they enter the provincial public school system and English becomes the sole language of instruction. In 2016, the Canadian government announced the development of a Canadian Indigenous Languages Act intended to further strengthen and revitalize Indigenous languages, but its details are not yet known [41].

A Legacy of Educational Discrimination

Canada’s current commitment to diversity stands in contrast to treatment of Canada’s indigenous population historically, and in the recent past. From the seventeenth century onwards, French and English fur traders established colonies on lands already populated by a varied and diverse population of indigenous peoples, who now make up about 4.3 percent [42] of Canada’s population. Education was one means that European colonialists used to subjugate Canada’s aboriginal people. Beginning in the 19th century, indigenous “First Nations” children were forcibly placed in Residential Schools which represented, according to 2015 report released by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada [43], “an attack on Aboriginal children and families.”

While the residential schools policy was formally abandoned in 1969, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report states that “the last federally supported residential schools remained in operation until the late 1990s.”https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/committee/411/appa/rep/rep03dec11-e.pdf [44]http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Exec_Summary_2015_05_31_web_o.pdf [43] This history continues to have a negative impact on the educational outcomes of Indigenous people, who tend to have lower educational attainment than non-indigenous groups. For instance, only 9.8 percent [45] of indigenous people held a university degree in 2011, compared to 26.5 percent of the non-indigenous population. According to most accounts, this attainment gap has recently been widening [46], or at best remained stagnant [47]. Policy discussions about improving education and funding for Indigenous schools continue [48] until today [49], and include recommendations to advance bilingual education [50].

Elementary and Secondary Education Systems in Canada

At both the elementary level and the secondary level, the structure of the education systems in Canada varies by province or territory.

The most obvious variation is that the elementary and secondary school cycle varies from eleven years in Quebec to twelve years in almost all other jurisdictions. Nova Scotia is sometimes described as having a thirteen-year cycle, starting with an additional grade called “Primary.” This grade is comparable to “pre-elementary” education in other jurisdictions. Other facts of note include the following:

- Depending on the province, elementary education begins at the age of either five or six. It is compulsory in all provinces. It lasts six years [51] in Quebec, and eight years in Ontario and New Brunswick.

- In the Northwest Territories, the last years of elementary education are called intermediate level.

- Curricula for elementary and secondary schools are determined by the provincial or territorial education authorities. All typically include mathematics, arts and languages, science and technology, and physical education.

- In a number of provinces, elementary school is followed by three or four years of middle or intermediate school, and finally three or four years of senior secondary school, which is also known as secondary or senior high school.

- In Quebec, six years of elementary school are followed by five years of secondary school, called Secondary I through Secondary III (Cycle I) and Secondary IV through Secondary V (Cycle II).

- Other provinces divide secondary education into junior and senior high school (also known as junior and senior secondary) or, in the case of Ontario, simply refer to the first eight years of education as elementary and years 9 through 12 as secondary school.

- In all provinces, promotion from one grade to the next and from elementary to secondary school is based on passing subjects rather than standardized exams. Instead, progression and placement are at the discretion of the individual schools themselves.

Note: Vocational education and training (VET) is of increasing importance in Canada due to high youth unemployment rates, population aging, and a shortage of skilled workers, which is estimated to amount to a lack of 1 million workers by 2020 [52], often in medium-skilled occupations [53]. At the secondary level, pupils can choose between academic and vocational high school pathways in most jurisdictions, depending on whether they plan to enter the work force directly or go on to higher education. In some cases, dual-track programs are available. Given the decentralized nature of Canada’s education system, a wide variety of both secondary and post-secondary VET options exist throughout the jurisdictions. Some are discussed below, although given the extensive variations, the discussion is, of necessity, only partial.

High School Graduation and Diplomas (Academic Pathway)

Secondary school graduation requirements are based, at a minimum, on gaining the requisite number of credits in compulsory and optional subjects. Additional criteria, such as passing provincial examinations or taking part in extracurricular communal activities, may also apply in some provinces.

The name of the credential awarded at the end of high school varies by region. Depending on where a student graduates, they may obtain ‘Grade 12 Standing,’ a ‘High School Diploma,’ a ‘High School Completion Certificate,’ or a ‘Graduation Certificate.’ In Quebec, completion of Secondary V (after eleven years of education) leads to the award of the Diplôme d’Etudes Secondaires or Secondary School Diploma.

Public and Private Schools at the Secondary Level

The vast majority of Canadian high school students attend public schools. Private education is, at a national scale, a minor phenomenon: Only 7.2 percent of secondary students were enrolled in private schools in 2013 (UIS [16]). However, enrollment numbers at private schools vary significantly by region [54], ranging from over 20 percent of grade 10 students in Quebec to less than one percent of grade 10 students on Prince Edward Island.

In general, Canada’s secondary education system produces high quality in terms of student outcomes. It fares well, for example, in the OECD’s comparative PISA study [55]. In the latest 2015 study, Canadian students tested above average [56] in science, reading, and mathematics. However, Canadian private school students generally outperform public school students in standardized tests by significant margins [54]. The effects of schooling versus socioeconomic status are difficult to parse: Young people at private schools are generally from more affluent families than their peers at public institutions, and they are more likely to have university-educated parents. These two factors may have a greater impact on academic performance than the curriculum or delivery provided by the school [54].

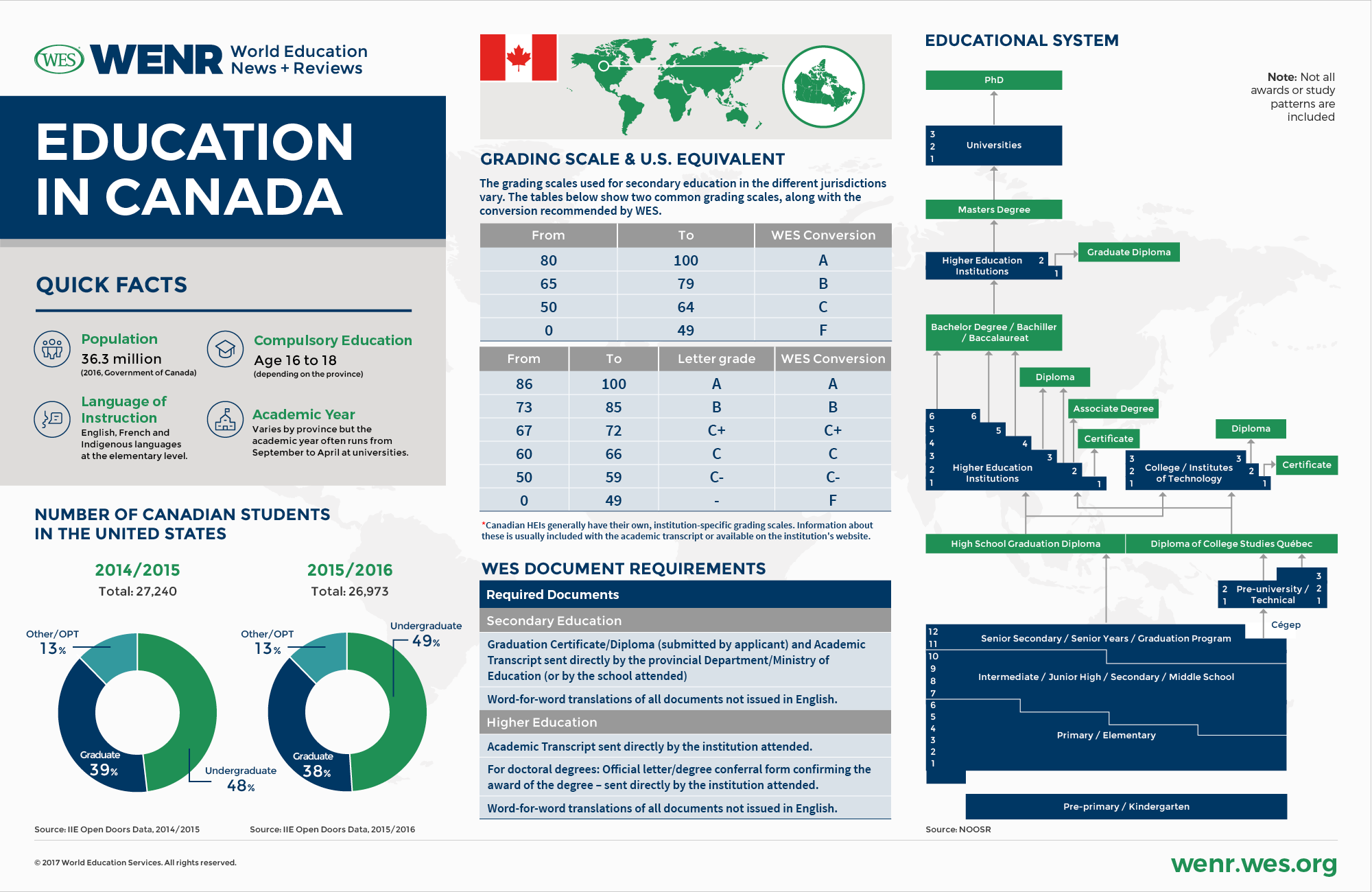

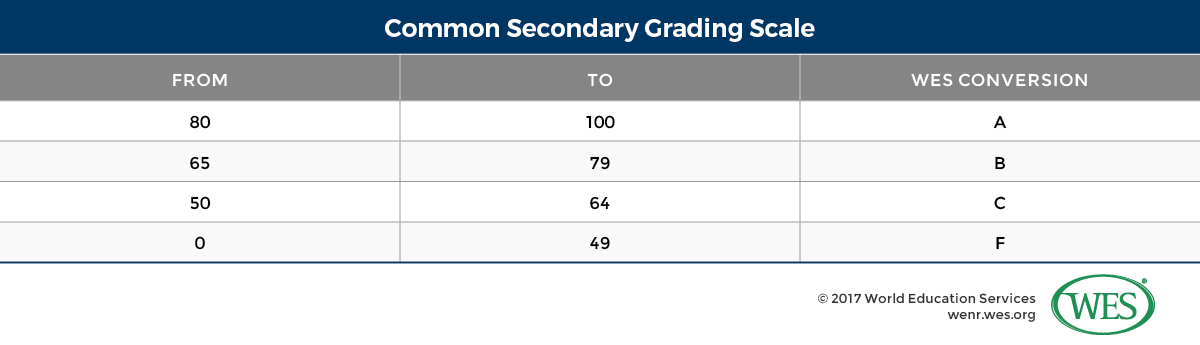

Grading Scales (Secondary)

Different provinces and territories employ different grading scales at the secondary level. The tables below show two common grading scales along with the conversion recommended by World Education Services (WES).

Secondary Vocational Pathways

Vocational pathways in Canada can be divided into three main tracks. These include:

- Credentials below the high-school-diploma benchmark

- Applied and vocational high school tracks leading to a vocational high school diploma

- Dual-track programs that allow pupils to begin apprenticeships or gain credit towards vocational credentials while still enrolled in high school

Pathways and credentials vary by province and territory.

Credentials Below the High-School-Diploma Benchmark

In Alberta, pupils in junior high school can enroll in the Alberta Career and Technology Foundations curriculum [59], and transition to the Career and Technology Studies curriculum in senior high school. Within the Career and Technology Studies curriculum there are nineteen “specialized skill pathways [60]” through which students can gain credits and credentials in specific fields of work, such as carpentry, welding, and architectural technology. Alternatively, students in grades 8 to 12 can take ‘Knowledge and Employability’ [61] courses in occupations such as construction, for example. After completing a set number of applied courses in combination with more academic courses (language arts, mathematics and science etc.), pupils can graduate with a ‘Certificate of High School Achievement’, which is below the benchmark of a high school diploma.

Vocational High School Diplomas

In Quebec, pupils in Secondary II can choose a vocational pathway in high schools. This prepares graduates for entry into the job market in fields such as healthcare and telecommunications, but some programs also give access to Quebec’s post-secondary colleges (discussed below). The number of students graduating with this type of diploma has increased considerably in recent years [62].

Students who complete this track are awarded secondary-level vocational credentials, the highest of which is the Diplôme d’Etudes Professionnelles, or Diploma in Vocational Studies. This

Dual-track Programs

There are a variety of dual-track programs inCanada. These programs combine applied vocational training with general high school education, allowing students to begin an apprenticeship while being enrolled full time in secondary school. The British Columbia Secondary School Apprenticeship [63], the Ontario Youth Apprenticeship [64], and similar programs in other provinces give students the option to graduate with a high school diploma as well as working towards a trade certification.

Similarly, New Brunswick’s three-year Labor Force and Skills Development Strategy includes provisions [65] through which students can gain high school credit for a seven-week trades program delivered by local community colleges.

Post-Secondary Education

Participation in post-secondary education in Canada has been growing strongly in recent decades despite the fact that Canada has an aging population [66]. In 2012, the country had one of the highest percentages of tertiary-educated people in the OECD, only surpassed by Korea and Japan. (Canada’s tertiary degree attainment rate of people aged 25 to 64, was 57 percent [67] compared to an OECD average of 32 percent,. The count includes both college and university graduates.) Mostly due to increased demand for skilled labor, participation in post-secondary education has more than doubled in the past decade from a total of 990,400 [68] enrolled full and part-time students in 2003 -2004 to 2,054,943 students [69] in 2014-2015. Of these students, 1.3 million, or 63 percent, were enrolled at universities.

Graduate enrollments in Canada rose from 77,000 students in 1980 to 190,000 in 2010 [66] (including 45,000 Ph.D. students), outstripping enrollments at other levels considerably. This growth is attributed [66], among other factors, to increases in research funding and scholarship programs, as well as the hiring of additional faculty members by universities.

Note: The term ‘university’ is generally reserved for degree-granting institutions that award bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees, whereas colleges usually only award diplomas. Some colleges [70], however, are authorized to award a limited number of bachelor’s degrees. According to the Council of Ministers of Education of Canada [71], there are at least 163 recognized universities (public and private) and 183 recognized public colleges and institutes in Canada, in addition to more than a 100 institutions authorized to offer specific programs. Unsurprisingly, the majority of institutions are located in the populous provinces of Ontario and Quebec. Both Prince Edward Island province and Newfoundland and Labrador province only have one university [72] (the University of Prince Edward Island and the Memorial University of Newfoundland). Technical and Vocational Training (VET) is also available at the post-secondary level.

Post-secondary Technical and Vocational Training

Post-secondary VET is offered at various types of non-tertiary institutions, including public colleges, community colleges, and technical institutes, as well as private career training colleges, about 500 of which are registered with and regulated by the National Association of Career Colleges [73] (NACC).

VET also takes place in apprenticeship or internship programs, which typically require four years to complete (7,200 hours) before concluding with a trade certification.

Apprenticeship Programs

The number of trainees in apprenticeship programs has grown significantly in recent years. Between 2000 and 2013, the annual number of people who completed an apprenticeship (journey persons) more than doubled from 20,000 to 47,000 [74]. There were 469,680 [74] actively registered trainees Canada-wide in 2013, the majority of them training in the occupations of Automotive Service Technician, Carpenter, Construction Electrician, Cook, Hairstylist, Equipment Technician, IT Support Associate, Plumber, Steamfitter/Pipefitter, and Welder.

Apprenticeships usually include 80 percent on-the-job training under supervision of a journeyperson, while the remainder of the program is devoted to classroom instruction. Apprenticeship training is contingent on an employment contract with a certified employer.

Trade certifications and apprenticeship programs are directly regulated by the individual provinces and territories. Since this creates challenges regarding the mobility and transferability of qualifications, an Apprentice Mobility Protocol [75] is in place to facilitate inter-jurisdictional recognition. At the federal level, the so-called ‘Red Seal Program [76]’ is used to harmonize training standards in designated trades across provinces, including a written interprovincial examination, certifying skills at the national level.

Despite these initiatives, a number of mobility challenges persist. Trainees who have not yet completed their apprenticeships may have difficulties fully transferring prior learning achievements [74] between employers in different provinces. In a recent publication [77] the OECD recommended augmenting the theoretical interprovincial Red Seal exams with a practical skills assessment and creating higher level VET programs in order to allow tradespeople to upgrade their skills to keep up with progressively complex technologies. As it stands now, journeypersons can seek admission to academic university programs, but presently have few options to train in higher level VET programs.

Colleges

Colleges throughout Canada offer a variety of post-secondary programs in both VET and academically oriented fields. These range from short-term, entry-level certificate programs lasting one or two semesters, to two- and three-year diploma programs. In some provinces, program structures are more formalized than in others. In Ontario, for instance, diploma programs are defined by the Ontario Qualifications Framework [78], and typically require two years of full-time study, whereas advanced diplomas require three years of study approved by the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Development [79]. Admission generally requires an Ontario secondary school diploma, although competitive programs may have additional grade requirements in specific subjects, and it is possible for older students above the age of 19 to be admitted without a diploma. A variety of articulation agreements and options for transfer credit [80] between colleges and universities exist.

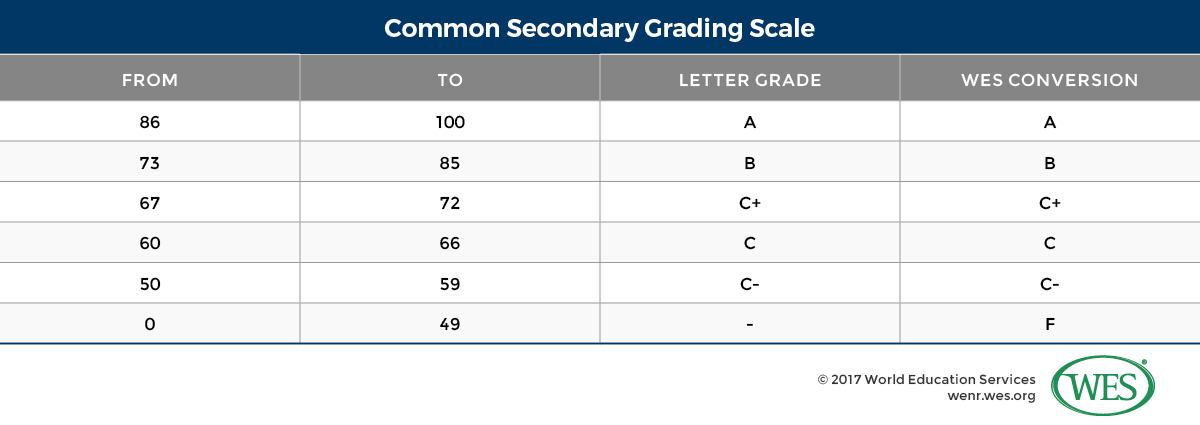

Quebec: Collèges d’enseignement général et professionnel (CEGEPs)

College education in Quebec is a special case because completion of a college program is usually mandatory for admission into tertiary university programs in the province. As a result, Quebec has the highest youth participation rate [81] in college education in Canada. There are 48 public Collèges d’enseignement général et professionnel (CEGEPs), five of them offer education in English [82] (in addition, there are a number of private colleges).

Public CEGEPs currently offer a range of 132 [83] vocationally oriented three-year technical diploma programs preparing graduates for specialized employment. In addition, students can enroll in two-year pre-university programs in 9 different streams. Both programs lead to the award of the Diplôme d’Etudes Collégiales, or Diploma of College Studies, commonly referred to as the DEC. The credential is issued by the Ministry of Education and constitutes the standard prerequisite for admission to tertiary education. Students also have the option of completing a Double DEC in 3 years, including a double major in two pre-university programs.

Higher Education

Higher Education Funding

Canada’s public higher education institutions are, to a large extent, directly funded by provincial governments, even though tuition fees have an increasingly important role in ensuring institutional solvency. In 2013-2014, an estimated 49 percent of revenues for higher education institutions came from government payments while tuition fees accounted for 24.7 percent, compared to 54 and 20.7 percent, respectively, in 2004-2005 [85]. According to the OECD [67], overall expenditures on education at all levels of education amounted to 13 percent of all public expenditures and 5.6 percent of GDP in 2011, an average figure compared to other OECD countries. At the same time, annual spending per tertiary student was well above the OECD average. While expenditures in the provinces and territories vary, total expenditures on post-secondary education at the federal level amounted to $ 12.3 billion CAD in 2013-2014 [85], up from $ 8.7 billion CAD in 2004-2005.

With the exception of a number of mostly faith-based private universities [86], the majority of universities in Canada are public institutions. This is true even though many universities classified as ‘public’ – for example, McGill University – were created as private institutions [87], but are considered public because they receive governmental funding.

Accreditation and Quality of Control of HEIs

Each of Canada’s provinces and territories determine their own criteria for establishing and controlling the quality of higher education institutions (HEIs). However, in the absence of a national ministry or accreditation body, “…. Membership of the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (AUCC) is… generally taken as evidence that an institution is providing university-level programs of acceptable standards [88],” according to the Canadian Information Centre for International Credentials (CICIC). In addition, a number of professional accreditation agencies [89] set quality standards and provide oversight in licensed professions at the national level.

HEIs in Canada can be “recognized,” “authorized,” “registered,” or “licensed” in one of the jurisdictions. Registered or licensed institutions are usually not scrutinized for academic quality, but merely overseen for compliance with consumer protection standards, although some provinces [90] may have voluntary accreditation mechanisms for these institutions (or programs).

Recognized and authorized HEIs, however, are approved by provincial charter or legislation to award educational credentials. Depending on the jurisdiction, institutions are obligated to implement internal quality assurance mechanisms and are subject to external peer review. A common model is to have internal quality assessments certified by governmental quality assurance agencies, but concrete mechanisms differ by province. An overview of legislative frameworks in the different jurisdictions can be found here [91].

External Perceptions of Quality: Rankings

A number of Canadian institutions typically appear among the top 100 in worldwide university rankings. The University of Toronto was ranked at 22nd, 27th,and 31st place in the 2016-2017 Times Higher Education Ranking [92], the 2016 Shanghai Ranking [93], and the 2018 QS World University Rankings [94], respectively. The University of British Columbia ranked 36th, 34th and 51st, whereas McGill reached 42nd, 36th and 32nd place, respectively. Also ranked among the top 100 were McMaster University (ranking 83rd in the Shanghai Ranking) and the University of Alberta (ranking 90th in the QS World University Rankings).

The Degree System: Undergraduate Education

Universities in most Canadian jurisdictions offer three-year and four-year bachelor’s degrees as the standard benchmark qualifications, requiring 90 and 120 credits for completion, respectively.

The exceptions to this pattern are Quebec and British Columbia: Whereas the standard undergraduate degree in Quebec is a three-year bachelor’s degree following the Diplôme d’Etudes Collégiales (or Diploma of College Studies), British Columbia normally offers four-year programs. Bachelor’s degrees are typically only awarded by universities but colleges with degree-granting authority are increasingly offering bachelor’s degrees as well. These colleges offer applied programs, which lead to a credential called Bachelor of Applied Science.

Both universities and colleges in British Columbia may also award two-year associate degrees.

Many jurisdictions also offer “honours bachelor’s degrees,” which are usually advanced 4-year programs. These may be required for admission to master’s programs in some provinces, and typically require higher academic performance and independent research.

Canadian HEIs generally have their own, institution-specific grading scales. Information about grading scales is usually included with the academic transcript or available on the institution’s website.

Admission Requirements

With the notable exception of Quebec’s 11+2+3 system, which requires completion of the Diplôme d’Etudes Collégiales for university admission, admission to higher education undergraduate programs across Canada generally requires a secondary school diploma. There are usually no entrance examinations but competency in one of the official languages is required.

Quebec and New Brunswick require proficiency in either French or English, whereas the rest of the provinces and territories require English language proficiency [95]. Beyond that, admission requirements vary by school and program. Overall, universities have stricter standards than colleges. A minimum GPA of 70 percent is required for both colleges and universities, but some colleges may accept students with a GPA lower than 60 percent. In-province applicants may have less strict requirements than out-of-province applicants.

Overview of Undergraduate Education in the Provinces and Territories

Alberta

Alberta follows the standard model of 3-year and 4-year bachelor’s degrees mentioned above. Four-year programs normally require more credits for completion than three-year programs. Athabasca University, for example, requires 90 credits for the award of its three-year Bachelor of Arts [96], whereas its four-year Bachelor of Arts [97] requires 120 credits. All programs have been externally reviewed and approved by Campus Alberta Quality Council since 2004. While four-year programs are more common, seven out of Alberta’s 17 recognized public and private higher degree-granting institutions offered both three-year programs and four-year programs as of 2017 [98].

Manitoba

Manitoba, similarly, offers three-year and four-year degree programs that are differentiated according to the breadth and scope of the program. For example, the University of Manitoba offers [99]:

- Three-year “general degree programs” (90 credits)

- Four-year “major programs” or “advanced degree programs,” which are “general education programs along with a reasonable degree of specialization” that are similar to honours programs, but usually do not include research courses (120 credits)

- Four-year “honours programs”, which are advanced, in-depth study programs with subject-specific specialization recommended for students who want to proceed to graduate study (120 credits)

Even though students with three-year general degrees are often required to complete pre-master bridging programs to be admitted into graduate programs, three-year degrees are still popular in Manitoba. In 2009, 1,551 students [100] graduated with three-year degrees, while only 237 and 231 graduated with four-year and honours degrees, respectively. Approximately 90 percent of four-year and honours degrees were awarded in the sciences.

British Columbia

In British Columbia, a bachelor’s degree is normally completed in eight semesters or more, requiring a minimum of 120 credits. Some programs may also integrate practical training [101] into the curriculum, for example, in the form of supervised internships at a work place.

Honours degrees have higher credit requirements: The University of British Columbia, for example, requires a minimum of 120 credits for general degree programs and 132 credits for honours degrees [102]. Many institutions also offer two-year associate degrees [103], which may be transferable into bachelor’s programs.

New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island

New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island follow the guidelines of a joint Maritime Provinces Higher Education Commission [104] in the design of their programs, which include both three and four-year degrees, as well as honours degrees. Most programs require eight semesters of study (120 credits), but general degrees can be completed within three years [105] (90 credits).

Newfoundland and Labrador

The education system of New Newfoundland and Labrador includes both three- and four-year bachelor’s degrees, although most standard programs offered at the Memorial University of Newfoundland, the only university in the province, are four years in length, including its Bachelor of Arts General Degree [106] (120 credits). For the award of an honours degree, students must meet additional requirements, including a minimum GPA of 70 percent or higher. The university also offers a range of co-operative bachelor’s programs which include practical work experience and take between four and five years to complete.

Ontario

According to the Ontario Qualifications Framework [78], the program length for a standard bachelor’s degree is six to eight semesters or 90 to 120 credits. Honours degrees, on the other hand, require at least eight semesters of study (120 credits), and may include additional requirements, such as practical internships

Over the past years, there have been debates in the province to phase out three-year bachelor’s degrees in favor of a four-year standard degree. The University of Toronto, the largest university in Ontario and one of Canada’s most prestigious institutions, has already abolished three-year programs, and the vast majority of Ontario’s students [107] currently graduate with four-year degrees. This trend is in line with a general decline in the number of three-year programs offered in many Canadian provinces [100], and corresponds to attitudes of students across Canada, most of whom consider four-year programs to be of better value and quality, as shown in past student surveys [108]. However, three-year degrees presently continue to be offered in Ontario by a number of institutions.

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan has two universities, the University of Saskatchewan and the University of Regina. The University of Saskatchewan offers three-year degrees (90 credits), four-year degrees (120 credits) and honours degrees with higher GPA requirements and greater curricular specializations. Honours degrees are recommended for students seeking admission into graduate programs [109].

The University of Regina offers four-year standard bachelor’s programs (120 credits), as well as honours degrees that require more advanced courses, including a research project [110].

Quebec

Because of Canada’s CEGEP system, which already provides a minimum of two years of academic training at the college level, bachelor’s degree programs in the French-speaking province are generally only three years in length (90 credits). The three-year degree is the standard admission requirement for master’s programs, which means that students graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Quebec’s 11+2+3 system are generally of the same age as students that seek entry to graduate programs in provinces with a 12+4 system.

The Northwest Territories, Nuvanut, and Yukon

Canada’s three territories are small in population size, and rely on cooperation with other provinces to provide higher education. Each territory has one college with the right to offer a number of degree programs in partnership with universities in one of the provinces.

Northwest Territories

Aurora College [111] offers two degree programs in addition to various certificate and diploma programs.

- Bachelor of Education: Four-year program offered in collaboration with the University of Saskatchewan [112].

- Bachelor of Science in Nursing: Four-year program offered in collaboration with a number of partner institutions in British Columbia, including the University of Victoria. [113]

Nunavut

Nunavut Arctic College (NAC) [114] offers two programs in collaboration with institutions in other provinces.

- Bachelor of Science in Arctic Nursing: Four-year program offered in collaboration with Dalhousie University [115] in Nova Scotia.

- Bachelor of Education: Four-year program offered in collaboration with the University of Regina [116] in Saskatchewan. NAC also offers a two-year post degree program leading to a “Bachelor of Education After degree” (BEAD).

Yukon

Yukon College [117] offers three programs in collaboration with institutions in other provinces

- Bachelor of Education: Four-year program in partnership with the University of Regina [118].

- Bachelor of Social Work: Four-year program offered in collaboration with the University of Regina [119]

- Bachelor of Science: Pathway programs offered in partnership with the University of Alberta [120]. Students typically complete 2 years at Yukon College and 2 years at the University of Alberta.

Master’s and Doctoral Degrees

Master’s programs in Canada are offered by graduate schools at universities. They are commonly two years in length, although one-, one-and-a-half, two-and-a-half and three year programs exist as well, depending on the major. Research-oriented programs usually include a thesis, whereas professionally-oriented programs may include an internship.

Admission is typically based on a four-year bachelor’s degree (three-year degree in Quebec) with an honours degree being a common requirement in some provinces. Individual institutions may have additional requirements, such as a minimum GPA or language skills. Universities also award post-graduate diplomas, which are typically one-year programs after a bachelor’s degree.

Doctoral degrees in Canada are structured programs that include at least one year of course work followed by qualifying exams and the preparation and defense of a dissertation. Programs are three years in length or longer. The final credential awarded in academic disciplines is the “Doctor of Philosophy.” Admission is based on the master’s degree, although some students may occasionally be admitted with a bachelor’s degree.

Professional Degrees

Professional degrees awarded in Canada include the Juris Doctor, Doctor of Medicine, Doctor of Dental Surgery and Doctor of Veterinary Medicine.

Admission requirements to these programs vary, but entail either completion of at least two to three years of prior university study or a bachelor’s degree. An overview of admission requirements [121] to Doctor of Medicine programs across Canada shows that many universities require a bachelor’s degree for admission into their four-year medicine programs, while some universities admit students based on three years of university study.

Universities in Quebec, however, generally admit students based on the DEC college diploma for a further four to five years of study. Licensure in medicine requires a medical degree and completion of a graduate medical education program of at least one year [122]. Additional requirements may be stipulated by regulatory authorities in the different provinces.

The Juris Doctor degree is typically awarded after completion of a three-year post-graduate program entered on the basis of bachelor’s degree, although some universities admit students upon completion of three years of undergraduate study. Licensing requirements vary by province [123], but usually require completion of an articling program (clerkship) after the award of the Juris Doctor.

Teacher Education

Eligibility to teach at elementary and secondary schools in Canadian jurisdictions generally requires a Bachelor of Education degree. Bachelor of Education programs are entered on the basis of a secondary school diploma (or DEC in Quebec) and usually last four years, including practice teaching, unless students enroll in five-year programs leading to the award of a concurrent Bachelor of Education/Bachelor of Arts and Sciences degree. Alternatively, holders of bachelor’s degrees in other disciplines can earn a consecutive one- or two-year Bachelor of Education degree on the basis of the first degree.

Challenges for Credential Evaluation: High School Documentation and Overseas Schools

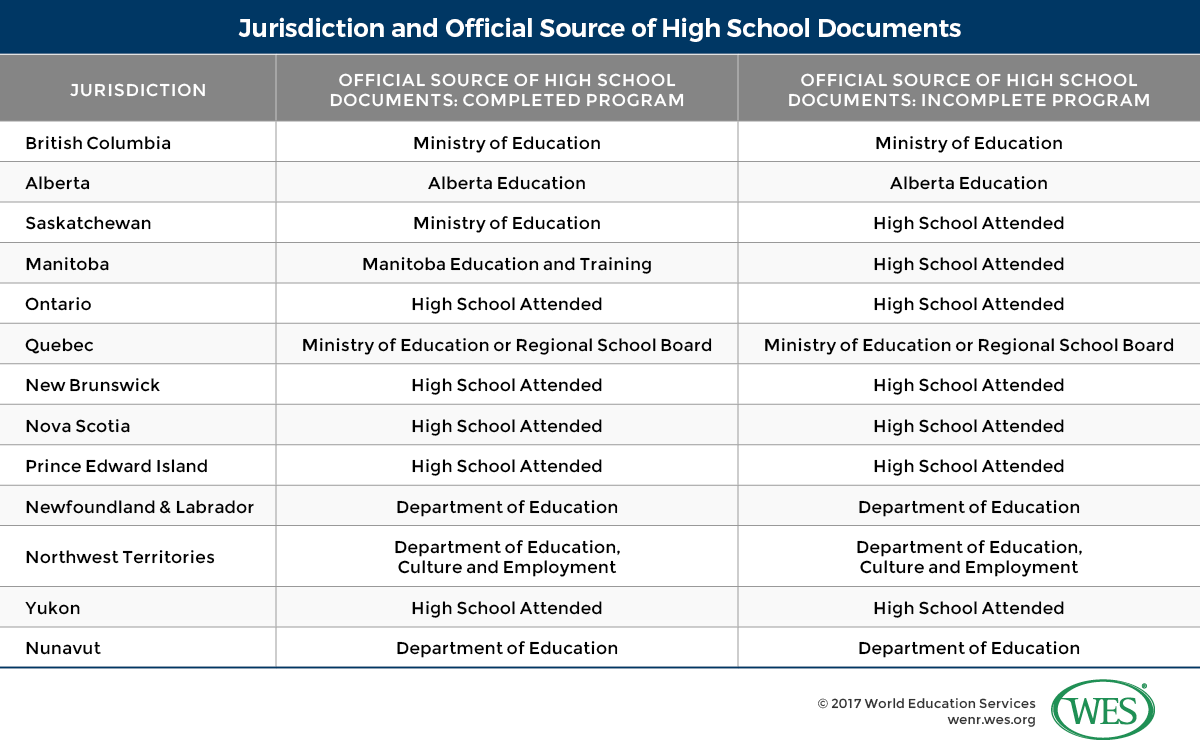

The decentralized nature of Canada’s education system poses a number of challenges for credential evaluation, particularly with regards to secondary education. Most jurisdictions have different names for their secondary school credentials – in both French and English –and the length of secondary school programs vary. Admissions officers need to be mindful of these differences when soliciting and reviewing official documentation for high school credentials. A complete high school transcript from Manitoba, for example, lists credits and grades for the four years leading to graduation, whereas a complete high school record from British Columbia covers only three years. As illustrated in the table below, the official source of high school documents depends on where the applicant went to school, and whether the program has been completed or not.

[124]

[124]

Also of note is the growing number of elementary and secondary schools outside of Canada seeking recognition from one of Canada’s provincial education departments. These schools are located all over the world, but are recognized by a Canadian ministry or education department and teach official Canadian curricula. It may not always be immediately apparent that these institutions are not under the auspices of the foreign country’s ministry of education, but are in fact Canadian international schools. We recommend that admissions officers consult the institution’s website and look up the schools on the list of offshore Canadian schools [125] provided by the Canadian Information Centre for International Credentials. Information on the recognition status of overseas schools can also be confirmed on the websites of the education authorities of Canada’s thirteen jurisdictions.

Document Requirements

Secondary Education

- Graduation Certificate/Diploma – submitted by the applicant

- Academic Transcript – sent directly by the Department/Ministry of Education (or alternatively by the school attended)

- Word-for-word translations of all documents not issued in English – submitted by the applicant

Higher Education

- Academic Transcript – sent directly by the institution attended

- For doctoral degrees: Official letter/degree conferral form confirming the award of the degree – sent directly by the institution attended.

- Word-for-word translations of all documents not issued in English – submitted by the applicant

For further details, see the WES website [126].

Sample Documents

Click here [127] for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Ontario Secondary School Diploma

- Diplôme d’Etudes Secondaires (Secondary School Diploma), Quebec.

- Associate of Science

- Bachelor of Commerce( 3 years)

- Bachelor of Medical Sciences ( Honors, 4 years)

- Diplôme d’Etudes Collégiales (Diploma of College Studies)

- Baccalaurėat (Bachelor), Quebec.

- Master of Arts

- Doctor of Philosophy

References

| ↑1 | Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies. |

|---|---|

| http://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/052642bb-3fd9-4828-b608-c81dff7e539c?_ga=1.129598988.1449264574.1482960422 [10]. | |

| ↑3 | Canada’s 10 provinces are Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Quebec, and Saskatchewan. The three territories are Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Yukon. |

| Statistics Canada [15]. | |

| for 39 percent of enrollments in 2013-2014, [18] with France being the biggest sending country, according to the Canadian government. | |

| ↑6 | These programs present challenges for credential evaluators. Tips on addressing tem are addressed at the end of this article. |

| delegated the governance [36] of education to the territorial governments. | |

| https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/committee/411/appa/rep/rep03dec11-e.pdf [44] | |

| http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Exec_Summary_2015_05_31_web_o.pdf [43] |