Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Although often overshadowed by Asian education markets, Latin America is a major source of international students around the globe, especially among institutions in the United States. In all, Latin American students now account for more than 7 percent of international enrollments on U.S. campuses. Four key countries, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela, rank among the top 25 sending markets to the U.S., and are poised to grow even more.[1]IIE, Open Doors 2015-2016 “All Places of Origin” https://www.iie.org/en/Research-and-Insights/Open-Doors/Data/International-Students/All-Places-of-Origin/2015-16. For the sake of comparison: Students from Europe accounted for 8.8 percent of international students in the U.S. in 2015-2016, while students from Southeast Asia accounted for 5.2 percent.

[2]In the very near term, it is fair to question whether U.S.-bound mobility from these countries will grow much, if at all. Each is facing circumstances that will affect students’ interest in or ability to study abroad in the U.S. or elsewhere. U.S. President Donald Trump’s inflammatory anti-Mexican rhetoric and policy positions, for instance, may already be leading to a considerable dip in Mexican students’ interest in pursuing higher education in the United States [3].economic gains [4] in the long term, is still nascent.

[2]In the very near term, it is fair to question whether U.S.-bound mobility from these countries will grow much, if at all. Each is facing circumstances that will affect students’ interest in or ability to study abroad in the U.S. or elsewhere. U.S. President Donald Trump’s inflammatory anti-Mexican rhetoric and policy positions, for instance, may already be leading to a considerable dip in Mexican students’ interest in pursuing higher education in the United States [3].economic gains [4] in the long term, is still nascent.

However, the longer term picture is far brighter, and these countries, as well as the larger Latin American region as a whole, are likely to emerge as even more substantial outbound markets for the U.S. and other countries.

The most relevant factors to consider include:

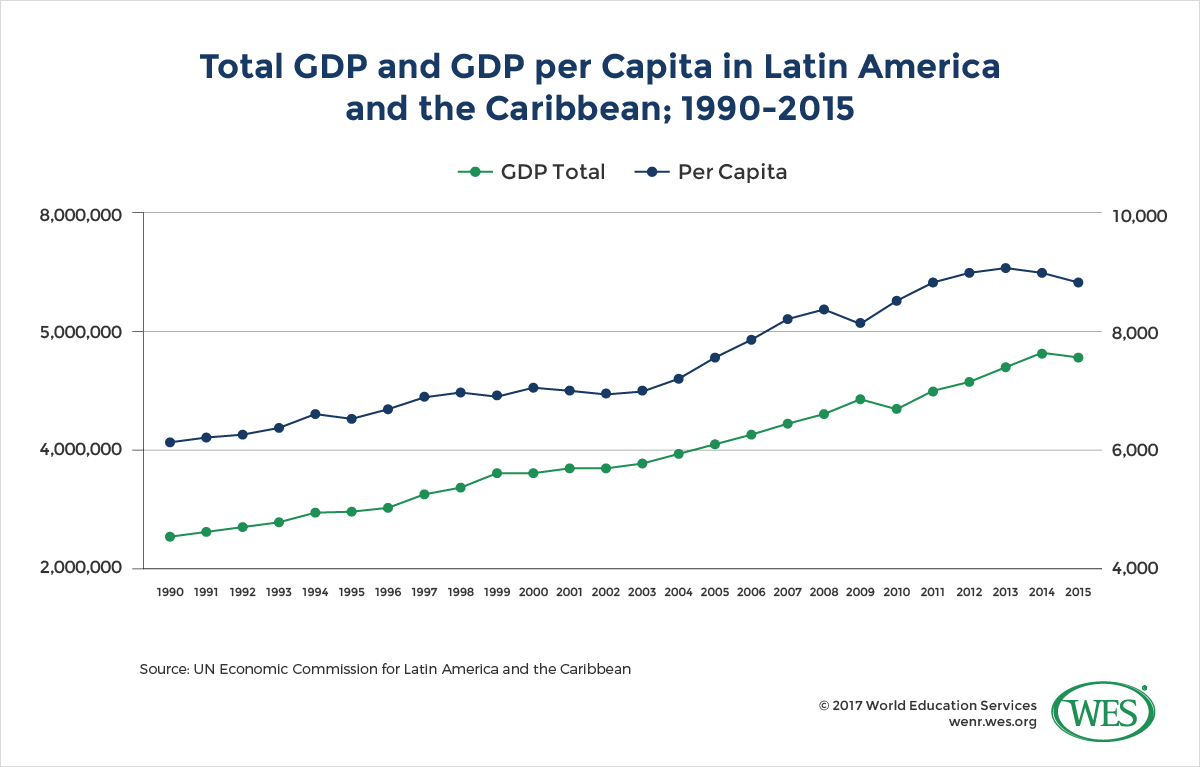

- Long term economic expansion. Economic growth in Latin America’s large middle-income countries, which include Brazil, Mexico, Venezuela, and Colombia, has created growing numbers of relatively affluent students ready to study abroad. Across the LAC region, per capita GDP increased by 50 percent [5] between 1990 and 2013, before beginning to decline in 2014. The United Nations [6], meanwhile, reports that LAC “added 90 million people to an emerging middle class from 2000-2012.” And as of 2016, Latin America’s middle class accounted for 35 percent of the total LAC population – an increase of 14 percent over the past decade.expected to resume in 2017 [7].

- Growing demand for English language skills. The needs of globalized labor markets have driven increased demand for English-language skills across multiple segments of Latin American societies. Governments, employers, individuals, and the higher education sector have begun to view English language skills as increasingly important. Given geographical proximity, the U.S. is an obvious beneficiary of this trend, and already a major destination country for English language training.

- The massification of higher education. Expanded capacity in Latin American education systems, including those in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela, has dramatically increased the number of students. Although many of these students are unlikely to head abroad, massification has created a larger pool of potential mobile students and has coincided with increased international student mobility from Latin America.

- Institutional interest in internationalization: Institutions in LAC countries have been relatively reluctant to embrace systematic internationalization strategies, especially when compared to countries in Europe or Asia. However, as the World Bank’s Francisco Marmolejo has noted, the tide has begun to change. Partnerships “between Latin American higher education institutions and higher education institutions in other regions are now no longer a new phenomenon or a novelty; they are a common strategy.”[4]Quoted from Tobenkin, David: Latin American Partnerships Cross Board, International Educator, March/April 2016, p. 27. Research bears this statement out. According to a recent article in NAFSA’s International Educator, “a total of 48 percent of Latin American and Caribbean [higher education institutions] surveyed in a 2013 report by the International Association of Universities… had discrete internationalization policies, with another 28 percent preparing such plans, and another 15 percent already including internationalization as part of their overall institutional strategy. Thus, 91 percent of the region’s HEIs have specific or general internationalization plans.”[5]International Educator, March, April 2016, NAFSA

Brazil: The Eighth-Leading Country of Origin For Students in the U.S.[6]IIE Open Doors Report, 2015/16

[9]Not so long ago, Brazil was on the brink of an economic breakthrough, seemingly poised to finally move beyond its ranking as an upper middle income country and emerge as one of the world’s top economies. As the New York Times’ Eduardo Porter [10] noted in 2016 [11], “from 2008 to 2013,… Brazil’s income per person grew 12 percent after inflation. Wages soared. The poverty rate plummeted. Even income inequality narrowed.”

[9]Not so long ago, Brazil was on the brink of an economic breakthrough, seemingly poised to finally move beyond its ranking as an upper middle income country and emerge as one of the world’s top economies. As the New York Times’ Eduardo Porter [10] noted in 2016 [11], “from 2008 to 2013,… Brazil’s income per person grew 12 percent after inflation. Wages soared. The poverty rate plummeted. Even income inequality narrowed.”

Today, however, the economic outlook in Latin America’s largest country is far less sunny. Beginning in 2014, Brazil descended into the worst economic downturn since the 1930s. In 2015, the country’s previously fast-growing economy contracted by 3.8 percent. The country saw another 3.6 percent drop [12] in economic output in 2016. A combination of factors, such as falling commodity prices [13] and high public [14] debt, forced the government to cut spending and raise taxes, resulting in unemployment shooting up to 12 percent [15] in 2016 while Brazil’s credit rating was downgraded to junk status [16].

The economic crisis was accompanied by a massive corruption scandal that paralyzed the political system. Half of Brazil’s members of parliament were implicated [17] in an ongoing corruption investigation that led to the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff in 2016. It was not until 2017 that the situation started to improve. Brazil is expected to come out of recession this year, although economic growth will likely remain close to zero [18], and unemployment is anticipated to remain high [19].

In terms of international student mobility, the fallout of the recent political and economic turmoil has been significant. Until 2014, the Brazilian government had invested strongly in science and innovation: The number of scientific publications [20] by Brazilian scientists surged, international research collaboration expanded, and public science budgets reached record highs [21] in 2013. But over the following three years, the bottom fell out. Brazil’s science budget was slashed by more than 40 percent [22], and funding dried up at both federal and state levels. In 2017, the federal government enacted further cuts of 44 percent. It also capped budget increases for science, higher education, and public health [23], tying future increases to inflation rates for 20 years – a move that has effectively frozen spending for the next two decades and will have a chilling effect on Brazilian science, which is already hurting from the suspension of prestigious research projects and declining scientific output [23]. One casualty of the spending cuts with immediate implications for student mobility was the Science without Borders program (Ciência sem Fronteiras [24]).

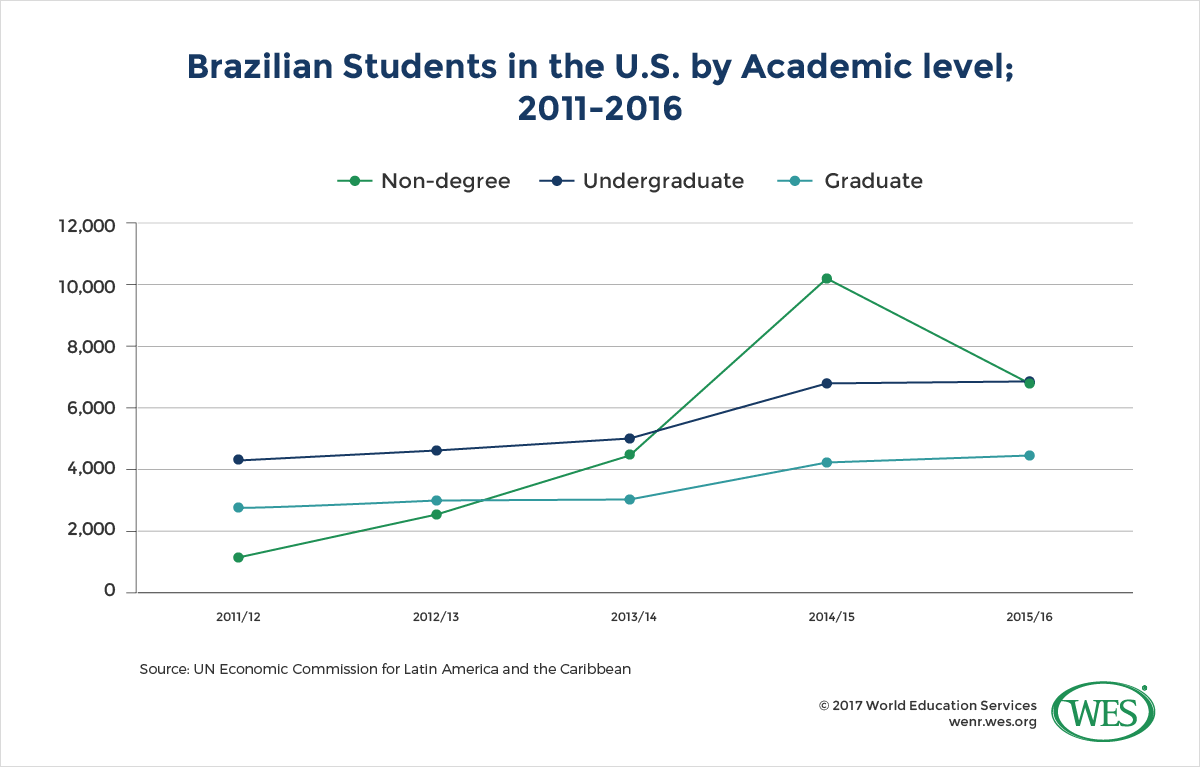

A hybrid public-private scholarship program intended to promote student exchange in order to internationalize Brazilian science, the Science without Borders (SWB) program helped send close to 100,000 Brazilian STEM students abroad between 2011 and 2015 [25]. SWB predominantly funded undergraduate, non-degree students to complete a year abroad, and had a sizable impact on international enrollments in a number of destination countries. As of January 2016, 79 percent [26] of SWB-funded students enrolled in undergraduate programs, the majority as engineering majors at institutions in English-speaking destinations. More than 25 percent of these students went to the United States. Smaller numbers of students enrolled in the U.K., Canada, followed by European countries like France and Germany, as well as Australia.[7] The mix of destinations for Brazilian students enrolled in degree programs as reported by UNESCO is slightly different. About 30 percent of Brazilian degree students abroad currently study in the U.S., while enrollments in other top destination countries like Portugal (13 percent), France (10 percent) and Germany (9 percent) are comparatively small. The total numbers of degree students enrolled abroad in 2016 were: U.S.: 13,349, Portugal: 5,438, France: 4,032 and Germany: 3,790.

In the U.S., the SWB program resulted in a surge of enrollments: Between 2010-2011 and 2015-2016, the number of Brazilians studying in the country increased by a stunning 170 percent, jumping from 8,777 to 23,675 students (Open Doors [27]). Originally slated to fund another 100,000 students through 2018, Science without Borders was officially suspended in April 2017. This formal suspension happened after the program had already been scaled back significantly [28], which led to a shortfall of 4,305 students in the U.S. (an 18 percent drop in enrollments) in 2015-2016. Given the program’s focus on non-degree students, however, the decline had something of a limited scope. While short-term enrollments plummeted, enrollments among degree-seeking Brazilian students on U.S. campuses actually increased from 2010-2011 through 2015-2016. Despite the economic downturn in Brazil and the scaling back of SWB, U.S. enrollments among undergraduate students grew by 65 percent, while those among graduate students increased by 46 percent (Open Doors [29]) during the five-year period.

What Will Outbound Mobility from Brazil Look Like in the Future?

Despite Brazil’s recent economic downturn and the demise of SWB, the long-term outlook for outbound mobility from Brazil is promising. Consider:

- Even at its height, economic turmoil had little effect on outbound mobility among Brazilian degree-seeking students. Per UNESCO [31], outbound international mobility among degree-seeking students remained relatively stable between 2011 and 2016. A recent survey by the Brazilian Educational and Language Travel Association (BELTA) found that the number of Brazilians studying abroad even increased by 14 percent [32] between 2015 and 2016.

- Brazil has relatively low tertiary-level enrollment levels, and high labor-market demand for educated workers. As of 2015, only 14 percent [33] of Brazilian adults had attained tertiary education, compared to 22 percent in Colombia – this despite the fact that between 2003 and 2013 tertiary enrollments exploded by more than 300 percent while the country’s median household income reportedly grew by 87 percent. The continuing scarcity of highly educated workers means that the wage premium for degree-holders is considerable. According to the OECD, a Brazilian “worker with a bachelor’s degree earns more than a worker whose highest level of achievement is upper secondary education,” while those with master’s or doctoral degrees earn more than four times as much.

- Brazil’s public research universities, most of which are concentrated in the state of São Paulo, have limited numbers of seats. Brazil’s higher education system is dominated by private institutions [34], many of which are considered sub-par [35]. The slashing of public science budgets may thus contribute to outbound mobility, by forcing Brazilian researchers to seek alternative opportunities [36] abroad, especially in countries which, like the U.S., offer a wider range of advanced scientific programs than are available in Brazil.

- Many of Brazil’s mobile students are self-funded [37]. This fact bodes well for mobility in the event of an economic recovery, even if the state budget keeps shrinking. Brazil’s currency, the real, has in 2017 appreciated [38] against the U.S. dollar, easing the financial costs for Brazilians coming to the United States. Canada has a comparative cost advantage [39] in this respect, which has, according to the Brazilian Educational and Language Travel Association (BELTA), recently turned the country into the most sought after study destination among Brazilian language students, ahead of the United States.

- Brazil’s government and universities remain committed to internationalization despite financial constraints. Although the Science without Borders program has been suspended, Brazil’s Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), a federal agency under the education ministry, is launching a smaller program focused on sending graduate students and postdoctoral researchers abroad. [40] Called More Science, More Development, the new program will provide participating universities with the funds to send graduate-level science students to institutions in other countries, rather than funding short-term students directly.

- Demand for English-language education in Brazil is on the rise. BELTA, which reports on short-term language programs as well as longer term enrollments, estimates that the number of Brazilians taking English courses abroad increased by 600 percent [41] between 2003 and 2013. Demand for English language education is likely to also drive mobility at the tertiary level. ICEF Monitor has noted [39] a recent shift to enrollments in cheaper English-speaking countries. The number of Brazilian degree students in Ireland, for example, increased by 558 percent between 2013 and 2015 (NOTE: Total numbers remain insubstantial: 283 students in 2015, per UNESCO.) Brazilian enrollments at Canadian institutions, meanwhile, increased by 66 percent between 2012 and 2015, according to the statistics provided by Canada’s government.top 50 countries of citizenship [42], 2006 to 2015, published by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). The number of students increased from 8,254 in 2012 to 13,720 in 2015, a slight drop from 14,316 students in 2014. Note that student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, IIE and governments may be inconsistent. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.).

Deeper Insight: Latin America’s Rising Demand For English-Language Skills

English-language education is viewed across Latin America as a pathway to economic integration for both individuals and nations. Mexico is a case in point: In one 2016 British Council study [43], researchers found that “Mexicans view English as a skill needed for greater employability”; that “Mexico has a substantial English learning market with around 20 percent of the population accessing English tutoring via public or private means”; and that 69 percent of Mexican employers “felt English was an essential skill when hiring new staff.” In Brazil, meanwhile, the number of students enrolled in English-language study courses abroad reportedly increased by 600 percent [44] between 2003 and 2013.

A shortage of English-language instructors [45] in Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia is another indicator of widespread demand, as is the growing interest across Latin America [46] in digital English language learning tools, including mobile apps, activities, e-Books, games, videos, audio clips, digital software, learning lab equipment, and online tutoring.

Spurred by the demand for English-speaking labor [47] by foreign companies investing in Latin America, governments across the region have begun to prioritize English-language education [48] as a means of integration into the globalized economy. English Proficiency Index [49]. Universities have also begun to introduce English as a language of instruction. Still, English language instruction at the tertiary level remains something of a rarity, and demand for language skills among employers and individuals is likely to fuel international student mobility to English-speaking countries – especially those in North America – in the coming years.

Colombia: The 23rd-Leading Country of Origin For Students in the U.S.[10]IIE Open Doors Report, 2015/16

The outlook for outbound student mobility in Colombia is promising. Marred by decades of civil war and political instability, the country has in recent years seen sustained economic growth and renewed political stability — a turn of events known as the “Colombian Miracle [50].” Already in a better economic position than neighboring economies, Colombia is expected to further benefit from the end of the civil war in 2016. GDP per capita has more than doubled since 1997 [51], making Colombia, a country of 48.6 million people (World Bank), the fourth-largest economy in Latin America. The World Bank forecasts that the country’s GDP will grow by 2 percent in 2017 [52], followed by projected growth of 3.1 and 3.4 percent in 2018 and 2019. Despite this progress, income distribution among Colombians remains among the most unequal in the world (OECD [53])

In pursuit of its goal of becoming Latin America’s most educated society by 2025 [54], Colombia spends more on education as a percentage of its GDP than other LAC countries (6.6 percent in 2013 [55]).marking the first time in the country’s history that the education budget surpassed the budget for defense spending [56]. Most funds go to elementary and secondary schooling.

Colombia may or may not achieve its regional educational ambitions, but it has already made considerable progress in terms of access to higher education: The number of students enrolled in tertiary education has more than doubled from about 1.1 million in 2004 to 2.29 million in 2015 (UIS [57]). Still, the net tertiary entry rate in 2015 stood at only 43.3 percent (UIS [57]), leaving ample room for expansion. Assuming that the country manages to address capacity shortages in its higher education system, tertiary enrollments are expected to surge even further.

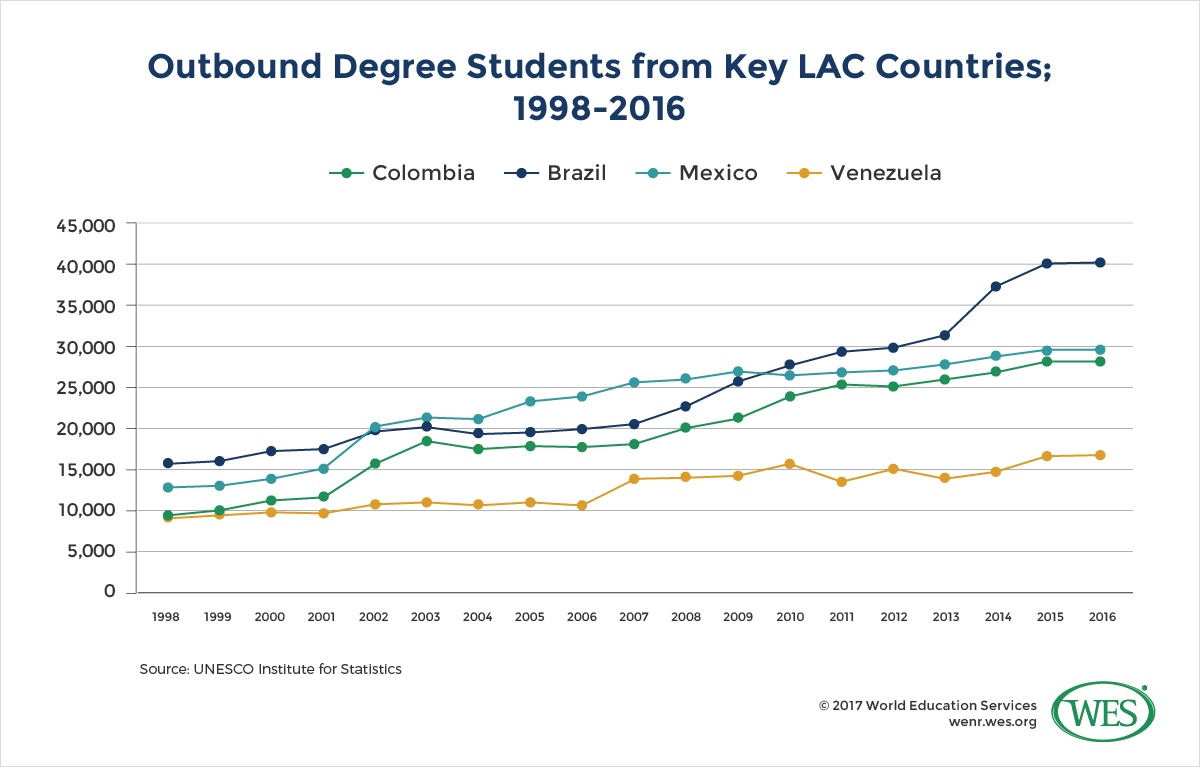

Both increased tertiary enrollments, as well as the prevalence of capacity shortages are likely to spur outbound mobility, with the U.S. standing to benefit from much of the potential growth. Historical data shows that outbound student mobility accelerated in tandem with domestic enrollments: The number of Colombian students seeking degrees abroad increased by 185 percent between 1998 and 2016, from 9,851 to 28,122 students (UIS [58]). Almost a quarter of these outbound students (6,831) are currently enrolled at U.S. institutions. Spain is the second most popular destination country (5,754 students), followed by France (2,559 students), and Germany (1,852 students).

While the number of students going to the U.S. strongly fluctuated over the past decades, enrollments increased by 21 percent between 2010-2011 and 2015-2016, making Colombia the 23rd leading country of origin for international students (Open Doors [59]). Colombian students in the U.S. enroll in undergraduate and graduate programs in equal parts.

Demand for English-language education among the country’s young population is bound to accelerate as Colombia grows more affluent. Many recruitment agents [60] in the language education sector already consider Colombia a highly dynamic growth market for ESL education – a fact that bodes well for tertiary mobility to English-speaking countries. Similarly, a 2015 study [61] by the British Council found that more and more Colombians view English skills as a key factor in employability, and the Colombian government promotes English education in an attempt to build an educated English-speaking labor force [61]. Government-sponsored scholarship programs for study abroad, including COLCIENCIAS [62] and COLFUTURO [63], have consequently funneled most recipients to English-speaking destinations: The U.S. and the U.K. are the most favored [64] overseas destinations [65] among graduate students funded by both programs.

One final consideration for U.S. institutions is the likelihood that the end of Colombia’s civil war will yield some form of “peace dividend” in higher education. U.S. universities have so far been relatively hesitant [66] to engage in transnational partnerships and research collaborations with Colombian HEIs, due, in part, to Colombia having been narrowly stereotyped as a country grappled by drug trafficking, crime, and armed conflict. The advent of political stability, coupled with growing interest among Colombia’s universities in partnerships, presents an opportunity for U.S. institutions to invest in what is still a relatively untapped market. The growing global reputation and research output [67] of Colombian universities is another consideration. The country’s future potential is such that it caused the Times Higher Education in 2016 to include Colombia on a list of seven countries [68] poised to become major players in higher education.

Deeper Insight: The Relationship Between Massification and Student Mobility

Once a privilege of the wealthy elite, tertiary education in Latin America is increasingly accessible to the masses. Between 1970 and 2000, the number of students enrolled in tertiary education in the LAC region increased by more than 600 percent, from 1.6 million to 11.4 million students [69]. The number is expected to shoot up to almost 60 million by 2035. Within less than 20 years, Mexico, Colombia, and Venezuela are projected to be among the world’s top 20 countries [69] in terms of tertiary enrollments. Brazil, by far the largest of the four countries under discussion, is expected to be among the top five.

On the one hand, expanded domestic opportunities lessen the pressure on students to leave. In fact, as noted in a 2017 study by the British Council [70], growth in university enrollments has, in a number of LAC countries, coincided with a decline in outbound mobility ratios (the percentage of mobile students among all students). However, in absolute terms, the growth of enrollments in higher education has accelerated outbound mobility from LAC countries. Both governments and academic institutions have simultaneously started to emphasize internationalization. Most of these internationalization strategies are geared towards increasing student mobility at the undergraduate level and focus on North America and Europe, whereas intra-regional exchange, as of now, is prioritized less frequently [71].

At the governmental level, this is reflected in the initiation of large-scale scholarship programs designed to promote exchange with English-speaking countries, particularly the United States. Mexico, for example, in 2013 launched “Proyecta 100,000 [72]”, an ambitious initiative seeking to boost Mexican enrollments in the U.S. to 100,000 students by 2018. Chile’s BECAS scholarship [73] program, likewise, is primarily focused on exchanges with partner institutions from the U.S., Europe and Australia. Perhaps most notably, Brazil’s now suspended “Science without Borders” program resulted in a massive influx of Brazilian students in English-speaking countries like the U.S., the U.K., and Canada.

It is also notable that in many countries, massification has largely occurred via privatization [74]. The percentage of enrollments at private higher education institutions (HEIs) in Chile and Brazil, for instance, is 84.6 percent and 73.9 percent, respectively (2015, UIS [57]). Many of the new private institutions are effectively “demand absorbing” – in other words, they provide students with access to higher education, but not the same level of academic quality or rigor offered by most public institutions. Limited access to quality education at the often competitive public institutions in Latin America is, thus, another factor motivating students to study abroad.

Mexico: The 10th-Leading Country of Origin For Students in the U.S.[12]IIE Open Doors Report, 2015/16

Mexico has long been regarded as one of the Americas most dynamic growth markets for international education. The fundamentals of continued outbound growth are all in place:

- The number of middle income households earning an annual salary of between USD $15,000 and $45,000 reportedly more than quadrupled within the past 15 years [75], and now account for about 47 percent [76] of all Mexican households in 2015.

- Mexico’s tertiary student population, meanwhile, almost doubled from 1.92 million to 3.6 million, between 2000 and 2015-2016, while the number of Mexicans enrolled in degree programs abroad increased by 104 percent, from 14,533 to 29,730 students (UIS).

- Mexico’s population is expected to increase from 127 million (2015) to 164 million in 2050 (UN medium variant projection), despite the fact that the country’s once-high birthrates have slowed considerably in recent years.

From the perspective of the United States, Mexico’s proximity adds to its potential as a growth market. Geography has not only helped make Mexicans the largest immigrant group [77] in the U.S. – it also influences many tertiary level students to seek educational attainment north of the border. About 50 percent of the country’s outbound degree students were enrolled in the U.S. in 2015. The next leading destinations, Spain and Germany, by comparison, only accounted for 8.3 percent and 7.5 percent of outbound degree students, respectively (UIS).[13]Total numbers reported by UIS are: U.S.: 14,962, Spain: 2,470 and Germany: 2,225 followed by France: 2,181, the U.K.: 1,645, and Canada: 1,500.

One of the reasons Mexican students go north to the U.S. has, historically at least, been the relative ease of enrolling at U.S. institutions with campuses in border states. In fact, more than 40 percent [78] of Mexican students study at institutions with campuses in close proximity to the border, such as the University of Texas, New Mexico State University, or Arizona State University. Some institutions even have campuses in close enough proximity that students are able to save on housing and tuition costs by living in Mexico while paying in-state tuition [79].University of Texas in El Paso [80] (the largest host university of Mexican students), as well as New Mexico State University, the University of North Texas [81] and Texas A&M University.

Political and Historical Context: NAFTA, the Bilateral Forum on Higher Education, Innovation, and Research, and Proyecta 100,000

Since 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has also influenced migration, economic integration, and partnerships among higher education institutions in both the U.S. and Canada.

In the wake of NAFTA, cross-border trade between the United States and Mexico grew to more than USD $ 1 billion [82] a day. The agreement made the U.S.-Mexico border the most frequently crossed land border in the world and led to an increase in cross-border investment. NAFTA also paved the way for a substantial number of university partnerships [78], dual degree programs, and research collaborations between institutions in Mexico and the U.S., particularly those close to the border. Overall, the number of Mexican students in the U.S. has almost doubled from 9.641 students in 1998-1999 to 16,733 students in 2015-2016. Most are enrolled at the undergraduate level. [83]

The governments of both countries have, in recent years, attempted to capitalize on this dynamic. In 2013, the U.S. and Mexico established a Bilateral Forum on Higher Education, Innovation, and Research [84] to promote student exchange and research collaboration. That same year, Mexico’s government announced “Proyecta 100,000 [85]”, an initiative focused on scholarships and university partnerships as a way to boost Mexican enrollments in the U.S. to 100,000 by 2018, while simultaneously increasing the number of U.S. students in Mexico to 50,000. Between 2012-2013 and 2014-2015, Mexican enrollments in the U.S. were on a steep upward trajectory, increasing by as much as 15.4 percent.

Recent Trends: The Trump Effect

The recent deterioration in the relationship between the United States and Mexico, however, has stanched this movement, at least for the time being. The day after Donald Trump won the presidential election, the Mexican peso plunged to a record low [86]. More than 80 percent [87] of Mexican exports go to the U.S., and the Mexican economy would be badly hurt should the Trump administration enact its anti-free trade agenda and annul the NAFTA treaty. An economic downturn and restrictions on cross-border movements would be all but conducive to student mobility. A trade war with Mexico is not in the interest of large parts of the U.S. industry and might not materialize in full.

But Trump’s policy positions have negatively affected Mexican public opinion and student views from the very beginning of his presidential campaign, which was steeped in anti-Mexican demagoguery [88]. A survey of 40,000 international students conducted in March 2016 [89] found that as many as 8 in 10 Mexican students were less likely to study in the U.S. should Donald Trump win the election – far more than the global average of 6 out of 10.

A PEW public opinion poll [90] in the spring of 2017 found that favorable views of the U.S. in Mexico had dropped by 36 percent since President Trump took office – the steepest decline among all countries surveyed. Only 30 percent of Mexicans now hold positive views of the U.S. while confidence in Trump stood at merely 5 percent, the lowest rating of any U.S. president since PEW began polling in Mexico. Some observers have noted that this growing negativity towards the U.S. is a factor [91] improving the chances of the leftist opposition to unseat Mexico’s increasingly unpopular PRI government in general elections in 2018, a prospect that could further worsen the already strained U.S.-Mexican relations.

Negative views are also reflected in a waning enthusiasm among Mexican students to study in the United States. In 2016, Mexican enrollments already decreased by 1.9 percent (IIE, Open Doors [92]), likely foreshadowing further declines. Recent SEVIS data [93] has shown a drop of more than 14 percent in active Mexican student visas between November 2016 and May 2017, while individual institutions are reporting decreased enrollments as well. In April 2017, the University of California, for example, reported a 30 percent [94] decline in applications from Mexico.

Even though push factors in Mexico are strong and institutions like the University of Texas are presently trying to expand recruitment [95] in Mexico, it is difficult to see student flows from Mexico returning to a solid growth trajectory in the near term. While the U.S. will certainly continue to be the most important destination country for Mexican students, we anticipate year-end data to reflect a decline in enrollments in 2017, and that mobility from Mexico will be characterized by uncertainty in the near-term future.

Additional Destinations for Mexican Students: Canada Looms Large

In light of these uncertainties, Mexican universities may seek to increase partnerships with European universities. The number of Mexican degree students in Germany and the U.K. already increased by 23 percent and 32 percent between 2013 and 2016, respectively (UIS). But the country that is perhaps best positioned to benefit from shifts in study destinations is the third NAFTA signatory, Canada.

While the number of Mexican students enrolled in degree-granting programs in Canada is small (it stood at only 1,500 in 2013 as per UIS), the total number of Mexican students in Canada has increased substantially in recent years, driven to a large extent by the inflow of short-term English-language training (ELT) students.

Demand for ELT in Mexico is growing steadily, driven by multiple factors, including the internationalization of Mexico’s economy, its need for human capital, foreign investment, and its tourism industry. For many Mexicans, English-language acquisition is an investment that is positively correlated [43] with occupational status and household income. By some estimates, the number of outbound ELT students from Mexico increased by 35 percent [96] between 2011 and 2013, making Mexico the 18th-largest market for ELT in the world. With study in the U.S. currently a questionable option, Canada may emerge as the next most obvious choice. By some estimates [96], Canada’s share of Mexico’s mobile ELT market already surpasses that of the United States, and Mexican enrollments in ELT programs in Canada grew by 31 percent over the past decade, reaching 8,241 students [42] in 2016. Canada is currently seeking to attract even greater numbers of Mexican ELT students by expanding air service with Mexico, and removing visa requirements [97] for Mexicans arriving for short-term study visits of up to six months.

Canada may see increased enrollments among degree seekers as well. The country’s international education strategy [98], unveiled in 2014, identifies Mexico as a priority recruitment market. Recent efforts to establish a viable pathway from international study in Canada to permanent residency may also hold appeal for many Mexican students. Governments and universities on both sides, meanwhile, have recently adopted measures [99] to boost student mobility, including new scholarship programs and bilateral research agreements.

In the long term, Mexican students’ interest will likely bend again toward institutions in the United States. The country’s geographic proximity and inter-connectivity with the U.S.; existing migrant networks; current economic growth trajectory; rising education levels; and domestic enrollments are all factors that make increased mobility to the U.S. highly likely once political relationships have stabilized.

Venezuela: The 20th-Leading Country of Origin For Students in the U.S.[15]IIE Open Doors Report, 2015/16

Venezuela is currently characterized by strong political and economic instability. The collapse of crude oil prices in 2016 caused a severe economic crisis in the oil-rich nation, which derives more than 90 percent of its export revenues from crude. The collapse of the economy left the government unable to provide public services and food security. Inflation reportedly reached 800 percent in 2016 while the economy shrank by 18.6 percent [100]. The country of 31.5 million people drifted into chaos in 2017, as opposition groups started to challenge the government in a conflict that could escalate into a civil war [101]. More than 120 people have been killed in violent street protests since March 2017. The country’s food supplies are depleted and crime rates are soaring. Venezuela’s government is running out of foreign currency reserves [102] amidst a collapsing economy and an estimated unemployment rate of 25 percent [103].

Given these circumstances, meaningful predictions about future student mobility are difficult to make. Outward mobility in Venezuela has been on an upward trajectory in recent years, driven by many of the same factors seen in other LAC markets, among them growing prosperity [105], decreased poverty, and surging enrollments [106] in tertiary education. Between 1998 and 2016, for instance, the number of international Venezuelan degree students increased by 79 percent, from 9,395 to 16,810 students (UIS). About half of these students are enrolled in the U.S., where Venezuela is presently the 20th leading place of origin of foreign students, ahead of Colombia. The overwhelming majority of Venezuelan students in the U.S. are enrolled at the undergraduate level (IIE, Open Doors).

Financial challenges stemming from the deteriorating value [107] of Venezuela’s currency and the loss of stipends [108], however, may ultimately threaten outbound mobility to the U.S., even though student flows have so far not decreased. Venezuelan students abroad are currently struggling to obtain U.S. currency [109], a situation that is bound to deteriorate as Venezuela runs out of hard currency. The government has curtailed the exchange of Venezuelan bolivars into U.S. dollars, thereby burdening [110] Venezuelan students who were previously able to convert currency at favorable rates. Such problems notwithstanding, IIE data indicates that 2015-2016 enrollments in the U.S. actually increased by more than 30 percent over 2011-2012 numbers. Based on the latest student visa numbers [111] published by the Department of Homeland Security, they show few signs of decline. This suggests that student enrollments may, at least in part, be driven by students, including those impacted by the deterioration and closure of Venezuelan universities [112], seeking to escape the dire situation in Venezuela despite the prohibitive costs.

The level of outmigration and brain drain from Venezuela has increased considerably in the wake of the current crisis. By some estimates, 5 percent [113] of Venezuela’s people, especially skilled professionals, have already left the country, and a recent survey [114] found that almost 40 percent of Venezuelans were thinking of leaving. Indicative of this trend, visas issued to Venezuelans by Chile, for example, increased by 1,000 percent over the past five years [115], most of them work visas issued to young people aged 24 to 35. Large numbers of Venezuelans are also migrating to Argentina or fleeing to neighboring Brazil [116]. The number of worldwide asylum applications by Venezuelan citizens doubled between 2016 and 2017 [117], whereas asylum applications in the U.S. surged by 160 percent [118] between 2015 and 2016, making Venezuelans the largest group of asylum seekers for the first time in history.

As a country that shares a 1378-mile border with Venezuela, Colombia is most affected by migrant flows from Venezuela, and currently hosts anywhere between 300,000 and 1.2 million [117] Venezuelan migrants, depending on the estimate. While data on Venezuelan student enrollments in Colombia prior to 2014 is not available, Colombia is currently the second most important study destination of Venezuelan students – a notable exception in a region where international students typically head to the U.S. or Europe. A total of 2,088 Venezuelan degree students were enrolled at Colombian universities in 2015 (UIS), constituting the largest group of foreign students in the country. Outmigration from Venezuela will likely continue to have an impact on student enrollments abroad, but it remains to be seen if current enrollment levels in high-cost countries like the U.S. are sustainable, considering the dwindling financial resources of Venezuelan students.

References

| ↑1 | IIE, Open Doors 2015-2016 “All Places of Origin” https://www.iie.org/en/Research-and-Insights/Open-Doors/Data/International-Students/All-Places-of-Origin/2015-16. For the sake of comparison: Students from Europe accounted for 8.8 percent of international students in the U.S. in 2015-2016, while students from Southeast Asia accounted for 5.2 percent. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Analysis of the Department of Homeland Security’s Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS), indicates that between November 2016 and May 2017 – the period when the new presidential administration took office in the United States – inbound mobility from Mexico fell sharply by 14 percent. |

| ↑3 | Latin American Economic Outlook 2017 © OECD/United Nations/CAF 2016 |

| ↑4 | Quoted from Tobenkin, David: Latin American Partnerships Cross Board, International Educator, March/April 2016, p. 27. |

| ↑5 | International Educator, March, April 2016, NAFSA |

| ↑6, ↑10, ↑12, ↑15 | IIE Open Doors Report, 2015/16 |

| ↑7 | The mix of destinations for Brazilian students enrolled in degree programs as reported by UNESCO is slightly different. About 30 percent of Brazilian degree students abroad currently study in the U.S., while enrollments in other top destination countries like Portugal (13 percent), France (10 percent) and Germany (9 percent) are comparatively small. The total numbers of degree students enrolled abroad in 2016 were: U.S.: 13,349, Portugal: 5,438, France: 4,032 and Germany: 3,790. |

| top 50 countries of citizenship [42], 2006 to 2015, published by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). The number of students increased from 8,254 in 2012 to 13,720 in 2015, a slight drop from 14,316 students in 2014. Note that student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, IIE and governments may be inconsistent. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). | |

| English Proficiency Index [49]. | |

| ↑11 | Expenditures per student are still low by international comparison. |

| ↑13 | Total numbers reported by UIS are: U.S.: 14,962, Spain: 2,470 and Germany: 2,225 followed by France: 2,181, the U.K.: 1,645, and Canada: 1,500. |

| University of Texas in El Paso [80] (the largest host university of Mexican students), as well as New Mexico State University, the University of North Texas [81] and Texas A&M University. |