Cindy Le, Research Associate, WES

Canada is now the seventh leading destination for globally mobile international students [1] – and all signs point to further growth. But news reports of a precipitous spike in enrollments, together with the often-heard refrain that Canadian policies are uniformly welcoming to international students, may paint an overly simplistic portrait of the reasons behind that growth. This article examines enrollment trends going back to 2002, looks back to the patchwork of policies and practices that have affected student mobility to Canada, and provides insights for enrollment managers at institutions in the U.S. and elsewhere, who are seeking to support both international students and international education programs in the face of current geopolitical trends.

The Short View: Are We Seeing a Surge? Or Not?

Anecdotal reports lay down a simple narrative about current international students’ interest in Canada: In the wake of two major political shocks, the June 2016 British vote to exit the European Union (a.k.a., Brexit), and the November 2016 election of Donald Trump, international students suddenly began diverting their interest to Canadian universities en masse. As reported by the Vancouver Sun in May 2017: “Since May 2016, U.S. applications for undergraduate studies at [Montreal’s Concordia University] have increased by 23 per cent and by 74 per cent for graduate classes. Undergraduate applications from Mexico have jumped 325 per cent and by 233 per cent from India during the same period.” International applications to the University of Toronto meanwhile, had, as of May, risen by 22 percent.

The same month the Globe & Mail reported that acceptances by international students for the fall of 2017 were up considerably at some universities. The University of Alberta had a 27 percent increase over the prior year’s acceptances, for instance, while Queen’s University in Ontario had a 40 percent bump.

Data from Hotcourses, meanwhile, an online tool that lets international students research higher education options worldwide, also supports the notion that the “Trump effect” is real. According to Hotcourses data, 27.4 percent of Middle Eastern students on the platform (who numbered around 830,000) searched for the United States as a study destination between November 2015 and April 2016. Between November 2016 and April 2017, the percentage was just 19.7 percent. The attention directed at Canada, meanwhile, increased dramatically. From year to year, the fraction that searched for Canada as a study destination jumped from 41 percent to 89 percent. [1] Simon Emmett, Hotcourses Group, “Data Driving Decisions: Identifying Trends and Opportunities in Diversification Markets,” NAFSA Presentation, May 15, 2017

The Long View: A Slope

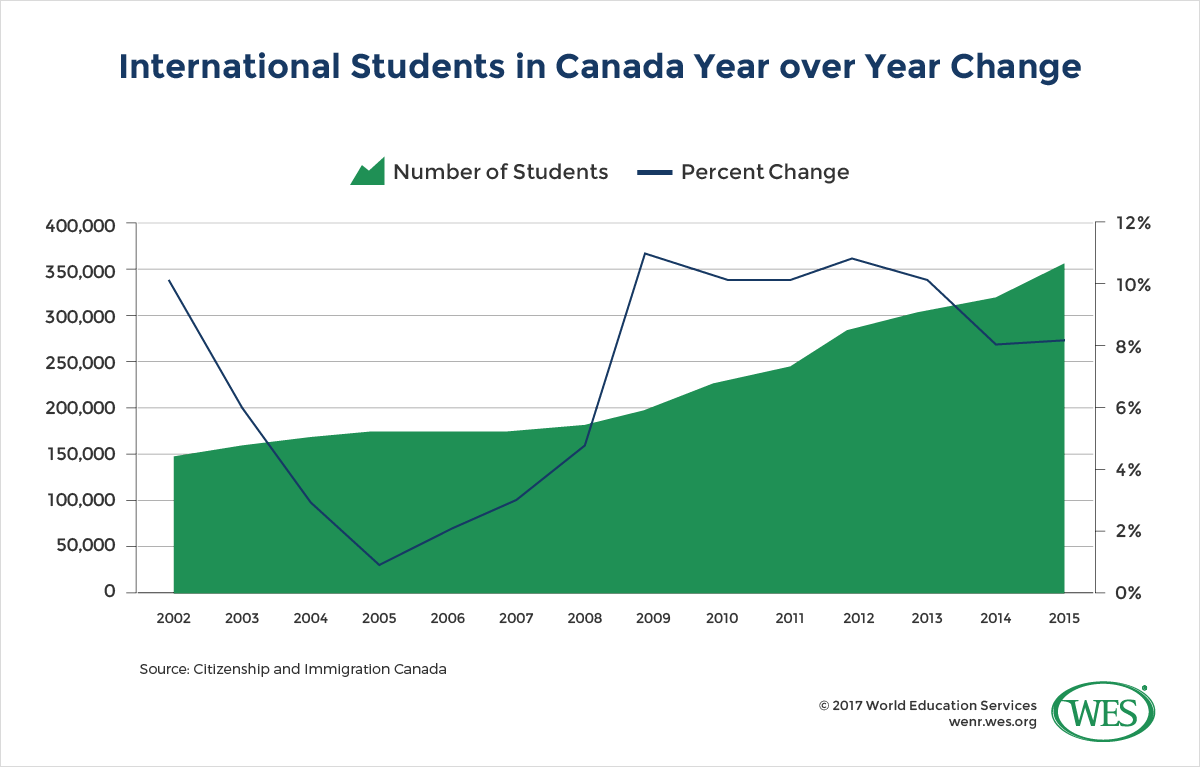

That said, much of the data gathered about current growth is, so far, anecdotal. It thus remains unclear whether what we are seeing is a long-term change, or a relatively small uptick in what has been steady, ongoing growth. “The long-term trend of expansion has held over the years, despite currency fluctuations and major economic and political events abroad,” Creso Sá [3], Director of the Centre for the Study of Canadian and International Higher Education (CIHE) at the University of Toronto’s Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, wrote earlier this year. “The surge that has been reported in international applications in 2017 cannot be divorced from … long-term trends.”

Sá makes another key point: This steady growth has often continued not due to Canadian policies and practices that pave any easy path for international students to enter the country, work in it, or become residents. Often, it has happened despite those that make it difficult. This view is confirmed by the government itself. “There is a lack of an effective whole-of-government approach between federal departments regarding international students,” stated a 2015 Citizen and Immigration Canada (CIC) evaluation [4] of the country’s international student program.

Policy and Practice: Diffuse Responsibility, Conflicting Signals

What of the oft-repeated refrain that Canada is welcoming to international students? Well, yes, and no. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s welcoming stance is well-documented, and in recent months, Canada has put forth a number of policies that explicitly encourage international enrollments.

Moreover, in 2014, the Canadian government unveiled an “International Education Strategy [5]” under the Ministry of Trade, signaling its intent to grow international student ranks as a form of economic competitive advantage.

But Canada’s ability to approach internationalization strategically is hampered by diffuse responsibility for implementation. As the Canada’s Immigration and Citizenship office noted in one 2015 report [4]:

“Several federal departments have a role related to international students in Canada,” including the CIC, the Canada Border Service Agency, and the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development. These “have their own mandates that sometimes work at cross-purposes.” Moreover, “education in Canada is the constitutional responsibility of the [country’s 13] provinces and territories. The federal government does not have jurisdiction (or legislative authority) to regulate education or its providers. As a result, a number of partners – all with different perspectives and priorities – share responsibilities with respect to international students.”

These challenges are not new. Over the last 16 years, inconsistent policies and practices related to international students have been the rule. What follows is a timeline of the visa and immigration policies and practices that have, in recent years, had an oftentimes contradictory effect on international students’ ability to pursue education in Canada. The timeline looks at a few select years, and evaluates the overall annual impact of immigration and international education related policy and practice with regard to student entry.

- 2001 – Net positive impact:

- In 2001, Canada passed the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), which came into full effect starting in 2002. The IRPA replaced the original Immigration Act passed in 1976 to oversee legislation regarding all immigration to Canada. The act eliminated the need for foreign students to obtain a study permit if they were registered in a course or program that lasted six months or less.[2]http://cbie.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/A-World-of-Learning-HI-RES-2016.pdf

- 2005 – Mixed impact:

- In 2005, Canada made two large changes to ease the application process for international students.

- First, the application for study permits was streamlined, allowing students to obtain a study permit for the full length of their period of study. Students were also permitted to transfer between programs of study or institutions without reapplication.[3]http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/evaluation/isp/2010/background.asp

- A new Post-Graduation Work Permit (PGWP) program enabled international student graduates from Canadian institutions outside of Montreal, Vancouver, and Toronto to work in Canada after graduation for up to two years.[4] http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/evaluation/isp/2010/background.asp However, stringent requirements meant that students had only 90 days from graduation to obtain a job offer in their field. Three years later the time limit was extended to three years.[5]http://www.levlaw.com/history-of-immigration-2000-2012/

- In 2005, Canada made two large changes to ease the application process for international students.

- 2006 – Positive impact:

- The Off-Campus Work Program (OCWP) was introduced, allowing international students to work up to 20 hours a week while in school, and providing them with valuable work experience in Canada. [6]http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/evaluation/isp/2010/background.asp However, a limited number of occupations were allowed to count toward residency requirements.

- 2008 – Mixed impact:

- The Canadian Experience Class (CEC) was implemented to provide an easier route to permanent residency for international students. However, work experience gained under OCWP did not count towards CEC residency requirements. Moreover, only certain occupations counted towards the work experience required for CEC. The net is that, while the program intended to support the recruitment and retention of international student graduates, it introduced additional barriers for some international students.[7]http://wenr.wes.org/2008/06/wenr-june-2008-feature

- 2010 – Negative impact:

- Canada’s immigration policies and practices in 2010 led to complaints from multiple countries. Slow visa processing times, especially for Saudi Arabian students,[8]https://thepienews.com/news/saudis-protest-at-canadian-visa-delays/ and the decision to bar visas from Indians who previously worked in defense and security institutions were among the most notable.[9]https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/indian-visa-uproar-prompts-canada-to-launch-immigration-policy-review/article4321034/

- 2012– Negative impact:

- The sudden closure of six visa offices in Germany, Japan, Iran, Malaysia, Bangladesh and Serbia threatened Canada’s ability to attract students in some corners of the world. The closures resulted in increased wait times for visas, in addition to forcing students to go through the time-consuming, uncertain, and expensive process of applying for visas through other countries’ embassies.[10]https://thepienews.com/news/canada-closes-six-visa-offices-abroad/

- 2013 – Negative impact:

- In 2013, new policies restricted the ability of anyone other than an immigration consultant, lawyer, or certified professional from providing immigration advice to international students. This prevented international student advisers at institutions of higher education from provding international students with advice about paths to immigration.[11]http://cbie.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/RISIA-Handbook_E.pdf These restrictions were mitigated in 2015, with the introduction of a new certification for ISAs who wish to become certified immigration advisers.[12]http://monitor.icef.com/2015/10/canada-launches-new-immigration-certification-for-international-student-advisors/

- New restrictions on work-study participation led to a 9.3 percent drop in the number of English-Language Training (ELT) students enrolled in Canadian schools or institutions.[13]https://thepienews.com/news/canada-9-3-drop-in-elt-students-in-2013/

- 2014 – Mixed impact:

- Canada released a national strategic plan which “[seeks] to attract 450,000 international students by 2022, [doubling] the number of international students currently studying in the country [at all levels].”[14]It’s important to note that this goal includes more than university age students. Per Statistics Canada, “International students come to Canada at various ages and attend various types of educational institutions. For example, some come to Canada through student exchange programs at the high school/secondary level while others come to obtain a post-graduate degree from a Canadian university. In short, they are a heterogeneous group… In the early 1990s, 43% of international students came to Canada to attend primary and secondary schools, while 18% pursued a university education. In the early 2010s, more international students attended universities (29%) than primary and secondary schools (22%).”

- The same year, Canada’s conservative government passed a law that raised the residency bar for international students, adding new barriers along the path to citizenship. This bill disallowed international students from counting time on Canadian campuses towards their residency requirements. The bill also raised the length of time required for permanent residents to become eligible for citizenship from four to six years.[15]http://cbie.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/A-World-of-Learning-HI-RES-2016.pdf

- 2015 – Negative impact:

- Canada’s Express Entry system, implemented in 2015, sought to ease the path to permanent residency for immigrants. However, it allocated insufficient points to international students, making it more difficult than before for them to obtain the points needed to become residents.[16]http://cbie.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/A-World-of-Learning-HI-RES-2016.pdf According to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), less than a quarter of Express Entry applications in 2015 went to those who had study experience in Canada.

- 2016 – Mixed impact:

- Revisions to the Canadian Express Entry immigration system [6] awarded extra points towards permanent residency for international graduates who attended Canadian universities. The residency requirements [7] for eligibility for citizenship were reduced from four years to three. Moreover, international students were permitted to count half of their time in Canada while in school towards this citizenship requirement. The changes to the immigration system increased the number of students invited to apply for permanent residence. There is one caveat to this positive picture: The Express Entry system has had some unintended consequences. The provincial nominee program (PNP) in Ontario, for instance, intended to streamline permanent residency applications. However, it had to stop accepting applications due to a large backlog of applicants. Many students feared losing their visa status before the program resumes.[17]https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/ontario-halts-residence-program-for-international-students-amid-backlog/article30054500/?ref=http://www.theglobeandmail.com&

- A study permit change in 2016 also required international students to obtain separate study permits for each programs pursued in sequence. For instance, if they completed a prerequisite program before their degree program, they would need a visa for each. The change raised questions about wait times and delays, and additional costs for international students.[18]https://thepienews.com/news/canada-concern-over-study-permits-rule-changeRefusal rates were also elevated, reportedly as high as 71 percent.[19]https://thepienews.com/analysis/international-student-visa-application-usa-uk-australia-canada-china/

- 2017 – Positive impact

- A newly passed law decreased the amount of time required for new immigrants to wait before becoming eligible to obtain Canadian citizenship. Residents must be in Canada for three years within a five-year period. (The previous requirement was four years within a six-year period.)The law also allows time spent in Canada on temporary work or study visas to count towards the residency requirement.[20]https://www.cicnews.com/2017/06/bill-c6-become-law-june-19-changing-canada-citizenship-act-069243.html

The Provincial View Beyond the Big Three: More Students Needed

The majority of international students in Canada are in just a few provinces – 86 percent are in Ontario, British Columbia, or Québec.[21]http://cbie.ca/media/facts-and-figures/ Attracting international talent to provinces that are more sparsely populated is one key to ensuring that students contribute to the widespread economic benefits the country is seeking. Through the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) different provinces in Canada can nominate immigrants that fulfill the economic needs of that particular province.[22]http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/immigrate/provincial/index.asp Recently, the program has become heavily weighted towards international graduates.[23]http://www.immigration.ca/new-immigration-policies-entice-international-students-study-canada/ A handful of provinces have begun to find innovative ways to attract international students. Nova Scotia, for instance, has launched a pilot program for international students as part of an effort to increase immigration into the province.[24]http://www.immigration.ca/nova-scotia-targets-international-students-boost-immigration/Graduates in the fields of health care, entrepreneurship, computer engineering, and ocean sciences who are admitted to the program will have their salaries subsidized.

The Takeaway

There are two interpretations of the latest reports on inbound student mobility to Canada.

- Canada is now the destination of choice for students alarmed by the political events in traditional destinations.

- Canada is, as it has been for more than a decade, one among many rising international education destinations around the globe with the potential to chip away at inbound flows to traditional higher education magnets like the U.S. and U.K.

Given that uncertainty, how should institutions in the U.S. and other countries react as they weather the current geopolitical climate?

- Ensure that communication of (and follow through on) the message that “you are welcome here [8].” Reach out to students now on campuses and to those still considering application or enrollment.

- Ensure that staff stay up to date with, and that leadership publicly respond to, events that may affect international students’ visa status. Give students practical information they need to make decisions that will protect their status. The University of Michigan and others offered a case study of what to do right on this front after a February 2017 executive order attempting to ban travel from seven countries threatened to make cross-border travel for international students and others difficult to impossible.

- Understand the needs and pain points of current international students, and address them. WES research has found that students from different regions of the world face very different challenges. Students from India struggle with homesickness, for instance, while those from China struggle with language, and those from MENA face prejudice. Providing relevant support services through relevant channels increases student success, and improves the word-of-mouth recommendations that can dramatically affect the perceptions of other potential enrollees within current student’s communities.

- Diversify source countries for international recruitment and enrollment. Over-reliance on any one county – India, Saudi Arabia, China , etc. – leaves your internationalization efforts vulnerable, if political or other winds suddenly lead students to consider other seemingly more friendly options.

- Plan recruitment targets as strategically as possible. Seek to understand both the potential return on investment of recruiting in one area versus another, and the opportunity cost of pursuing students from one country versus another. If you are from a small, non-ranked institution, try to find recruitment options off the beaten path, where viable enrollees may be less frequently courted than they are in major cities in top sending countries such as China and India.

The reality is that policies on immigration and other issues that affect international students change as governments or world events change. The impact on student flows, whether to the United States, Canada, or elsewhere, is uncertain.

In the face of these changes it makes sense for institutions to be both nimble and resolute. In the words of Robin-Matross Helms [9], director of the American Council on Education’s Center for Internationalization and Global Engagement, universities and others must “adapt: by responding swiftly, thoughtfully and effectively, and continuing to move forward… our work is too important not to [do so]. We owe it to our students to forge ahead with our commitment to developing their international knowledge and skills, and ensuring that they too can adapt and are well prepared to navigate whatever challenges they face in the increasingly globalized world.” [10]

References

| ↑1 | Simon Emmett, Hotcourses Group, “Data Driving Decisions: Identifying Trends and Opportunities in Diversification Markets,” NAFSA Presentation, May 15, 2017 |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑15, ↑16 | http://cbie.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/A-World-of-Learning-HI-RES-2016.pdf |

| ↑3, ↑6 | http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/evaluation/isp/2010/background.asp |

| ↑4 | http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/evaluation/isp/2010/background.asp |

| ↑5 | http://www.levlaw.com/history-of-immigration-2000-2012/ |

| ↑7 | http://wenr.wes.org/2008/06/wenr-june-2008-feature |

| ↑8 | https://thepienews.com/news/saudis-protest-at-canadian-visa-delays/ |

| ↑9 | https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/indian-visa-uproar-prompts-canada-to-launch-immigration-policy-review/article4321034/ |

| ↑10 | https://thepienews.com/news/canada-closes-six-visa-offices-abroad/ |

| ↑11 | http://cbie.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/RISIA-Handbook_E.pdf |

| ↑12 | http://monitor.icef.com/2015/10/canada-launches-new-immigration-certification-for-international-student-advisors/ |

| ↑13 | https://thepienews.com/news/canada-9-3-drop-in-elt-students-in-2013/ |

| ↑14 | It’s important to note that this goal includes more than university age students. Per Statistics Canada, “International students come to Canada at various ages and attend various types of educational institutions. For example, some come to Canada through student exchange programs at the high school/secondary level while others come to obtain a post-graduate degree from a Canadian university. In short, they are a heterogeneous group… In the early 1990s, 43% of international students came to Canada to attend primary and secondary schools, while 18% pursued a university education. In the early 2010s, more international students attended universities (29%) than primary and secondary schools (22%).” |

| ↑17 | https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/ontario-halts-residence-program-for-international-students-amid-backlog/article30054500/?ref=http://www.theglobeandmail.com& |

| ↑18 | https://thepienews.com/news/canada-concern-over-study-permits-rule-change |

| ↑19 | https://thepienews.com/analysis/international-student-visa-application-usa-uk-australia-canada-china/ |

| ↑20 | https://www.cicnews.com/2017/06/bill-c6-become-law-june-19-changing-canada-citizenship-act-069243.html |

| ↑21 | http://cbie.ca/media/facts-and-figures/ |

| ↑22 | http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/immigrate/provincial/index.asp |

| ↑23 | http://www.immigration.ca/new-immigration-policies-entice-international-students-study-canada/ |

| ↑24 | http://www.immigration.ca/nova-scotia-targets-international-students-boost-immigration/ |