By Alan Margolis

This article is reprinted from World Education News & Reviews, Volume I, Nos. 2, & 3, Winter & Spring 1988. Alan Margolis passed away on February 17, 2016. He was among the pioneers of international admissions and credential evaluation. Alan’s career included chairing the board of World Education Services, educational consultancy, and decades of service at CUNY, where he was the Senior Registrar at Queens College. He authored many influential publications and served as a teacher and mentor to generations of professionals in international admissions.

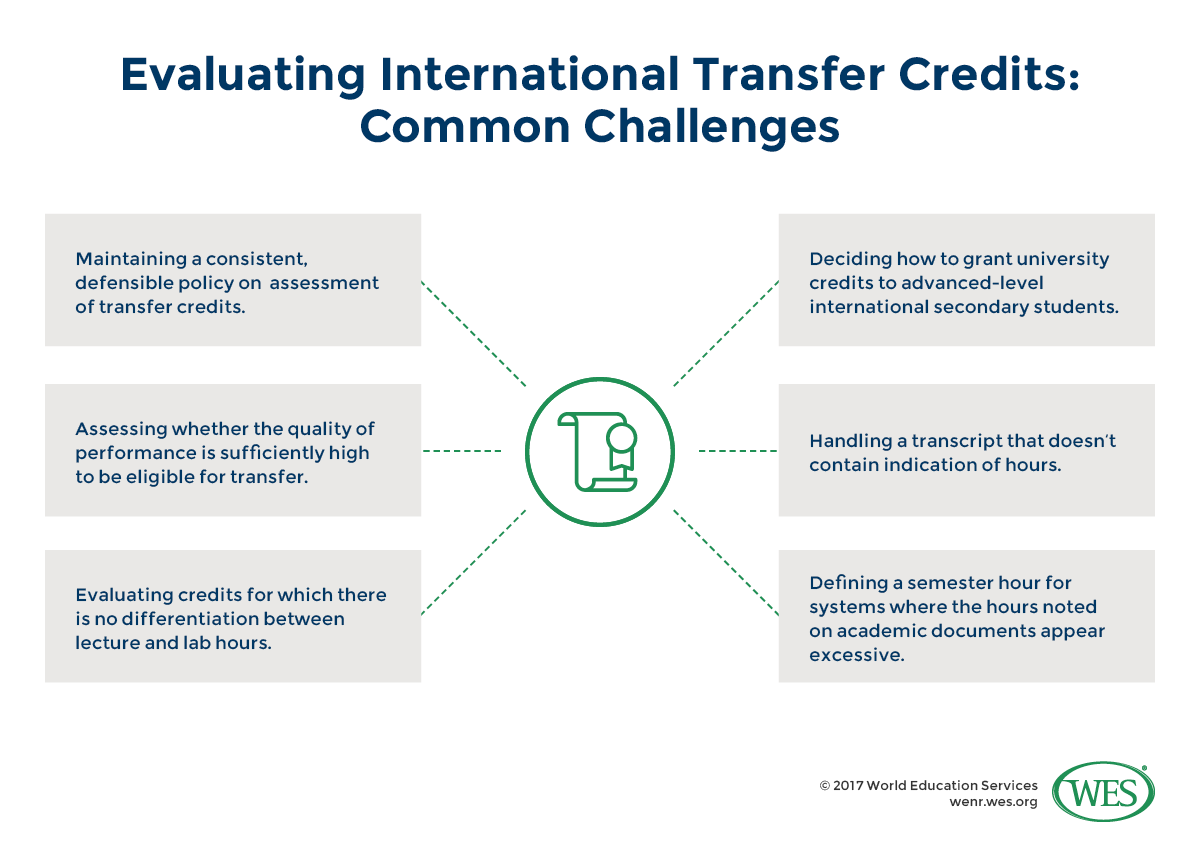

No aspect of the evaluation of undergraduate foreign credentials requires more intellectual rigor than the determination of transfer credit. In admitting freshmen, our view is totally outward. Based on applicants’ external education, we determine whether they possess the background with appropriate quality of performance to meet the standards we have set. We make little or no connection between previous experiences and our own curriculum, except to determine whether the student is likely to succeed in our environment. For example, in admitting freshmen engineering students, we seek the skills—generally a strong background in mathematics—that will meet the basic course requirements of the specialized program. And although CLEP and Advanced Placement programs allow freshmen to begin their collegiate life with a small number of credits in introductory courses, these constitute advanced-standing credit rather than transfer credit. This category represents so few credits, and their determination is so ritualized, that our intellectual involvement is minimal.

Transfer students, on the other hand, present us with a completely different set of problems. While the intellectual process used to admit them may be similar to that applied to freshmen—that is, the assessment of the ability of the students to perform successfully in our environment—the added dimension of assessing post-secondary-level coursework taken at a foreign institution [1] dominates the global decision-making process.

In dealing with foreign transfer credits, not only must one understand the general principles of credit transfer created for domestic circumstances, one must also be able to apply these principles to educational experiences for which they were not intended. What follows, then, is a review of those general principles.

General Principles

When granting credit to transfer students, assumptions are made that when viewed together, provide a basis for making judgments. The first assumption is that the previous work is equivalent in academic level to that offered at our own institution. The second is that the work is equivalent in substance and depth; i.e., that the depth of subject matter and the degree of specificity of knowledge, including differentiation between theory and practice, are comparable. The third is that performance levels are measured in a way comparable to how we measure performance, and that we understand the grading system.

For example, in evaluating the British “A” level examination in Chemistry, as one applies the assumptions above, one can determine whether to consider this level of achievement for credit as follows:

- Academic level equivalency: The Sixth Form (the two-year academic program that leads to the examination) requires prior secondary school work in chemistry (in fact, the passing of the “ordinary level” examination in chemistry) for admission. This prior work is, at minimum, equivalent to that taken at U.S. high schools. (It also needs to be noted that U.S. high schools do not usually require high school chemistry for admission into an introductory chemistry course.)

- Equivalency in substance and depth: A review of the syllabus will indicate that the subjects usually covered in a U.S. introductory chemistry course—inorganic, organic, physical, analytic—are covered in Sixth Form. (Laboratory work, however, may not always reach the standard of U.S. institutions.)

- Performance measurement: Grades are assigned for Sixth Form work, based on tests and laboratory reports. The “A level” examination is comprehensive and grades clearly represent distinct levels of achievement.

Thus, one can see that in applying these assumptions we can determine the acceptability of coursework for transfer. The actual quantification of credits, however, very well may be based on how the external work fits into our own courses.

Although the above discussion applies to all transfer credit regardless of whether the source is domestic or foreign, there are benchmarks that we accept as given within the U.S. educational system for convenience as well as for political reasons. For example, we accept work from within our own state or university system or from schools with which we have articulation agreements than from others. We may even accept lower grades for transfer credit from schools with which we have articulation agreements than from others. We do so for motives beyond the pedagogic assumptions dealt with above and often without reference to the potential for student success at our own institution.

Unless such a special arrangement exists with a foreign institution, these benchmarks do not apply to policies concerning foreign credential evaluations. Keeping this in mind, a basic principle comes into play: offer to foreign educated students only those benefits offered to students educated in the United States. If, for example, a Colombian student who has studied Latin in secondary school for six years petitions for credit by examination, then our regulations concerning credit by examination must be applied in a consistent fashion. If a U.S. student who has studied Latin in high school for four years may obtain credit by examination, then the Colombian should be able to as well.

Another example occurs when U.S. colleges give credit for native-language proficiency in foreign students’ first language if they have graduated from an academic secondary school. On the other hand, those domestic individuals who grew up in a bilingual environment do not get this opportunity for credit, even though their language proficiency may be may be equal to that of the native speaker. To be consistent, there should be a mechanism by which U.S. students are awarded credit for their foreign-language knowledge acquired at home.

Basic Considerations

Following are some basic considerations each that need to be reviewed only once in a theoretical environment in order to provide a modus operandi.

Accreditation

- Specific policies/practices concerning U.S. regionally accredited institutions and those in candidate status

- Specific policies/practices concerning transfer credit from institutions with other forms of U.S. accreditation

- Specific policies/practices concerning non-accredited institution

Credit and Grade

- Maximum total credit allowed in transfer

- Course credit quantification in the absence of credit hours

- Credit by external examination

- Credit by internal examination

- Criteria for determining elective credit including the limitation of the number of elective credits allowed

- Lowest acceptable grade for transfer

Documentation

- Source documentation: whether the “transcript” emanates from the institution (primary source), or from an agency or institution that may have evaluated the primary source, or may be an agent for that primary source (secondary source)

- Policies concerning the use of secondary source documentation: accepting transfer credits on other U.S. transcripts

- When one applies these considerations, the real question becomes whether they can or should be applied equally to domestic and foreign transfer evaluation. That answer will be different for each U.S. institution and may result in deviations from the standard placement recommendations as local policy supersedes general guidelines. It is not wrong to vary from what is accepted general practice as long as one is consistent with institutional policy and one applies, wherever possible, the same standards to all students regardless of educational background. There is no “wrong” when decisions are made with full understanding of the assumptions and principles that guide the institution and its processes.

Systemic Differences

While accreditation, credit and grade, and documentation provide the parameters for evaluation, the issues discussed below deal with the more comparative aspects of the process. In a sense, these first considerations are not arguable as they represent an extrapolation of institutional policy to foreign credential evaluation, an area usually not considered when transfer credit policy is legislated. In discussing the following comparative issues, one needs to address systemic differences—the single most difficult issue to view objectively and, therefore, frequently causes contention.

- The importance of systemic intent: the issue of what to do if the educational experience doesn’t fit

- The concept that “different is better”;

- The alleged superiority of certain foreign educational systems and the question of whether there are criteria for judging systemic superiority;

- The search for a means of arbitrating differences in opinion as to systemic superiority (the issue of perceptions based upon limited experience or to whom can one turn: e.g. the faculty member who spent a year abroad and returns as an “expert” on that country’s educational system and attempts to influence the evaluation process;

- The issue as to where the burden of proof resides.

Many admissions officers deal with academic level by counting years. Such a practice, of course, presupposes that there is a consistency among national systems as to program intent and intensity, a concept that is probably impossible to defend. Alternative criteria have been suggested: match years of study in each subject against the U.S. Carnegie unit (for determining high school equivalency): offer the foreign-educated person the opportunity to sit for challenge examinations either for exemption or for credit. There is some degree of comfort in dealing with the first of these because a quantification is possible and numbers, in some mystical way, serve as justification for our actions. The truth of the matter is that it is difficult to define a “standard” U.S. high school or university system against which to measure the foreign system. While counting years and/or courses can be valuable in decision-making, these qualifications should not be used as the sole criterion. One needs to take into account such relevant issues as program intensity and access from the level under consideration to further levels of education.

The first level of decision-making is to determine what is secondary education, i.e., where the break between secondary and tertiary level programs occurs. In formulating this determination, one must consider: Under what circumstances can ten years of elementary/secondary education be equated to U.S. high school graduation? Look at Nigeria or the United Kingdom. When is it appropriate to use the concept of “superior” when looking at foreign 12-year systems, for example, Belgium? What criteria need we develop in order to deal with systems that exceed 12 years? How do we look at 13- or 14-year programs, such as technical and teacher training programs in Egypt? This exercise is necessary since once the end of secondary education is defined, the beginning of tertiary education is easier to see.

At the higher level, one needs to be able to differentiate between undergraduate and graduate standings. For example, in France, is the licence or the maîtrise, the equivalent of the U.S. bachelor’s degree?

Some Common Approaches to Assigning Credit

The use of challenge examinations for foreign students, when this possibly is not open to domestic students, is often justified by noting that foreign students do not have the opportunity to sit for AP or CLEP examinations. Another school of thought argues that U.S. admission officers should consider external maturity/ matriculation examination results as if they were APs. Since the AP is defined as a test that certifies a level of knowledge beyond the expectations we have for secondary-school students, then we must reach a similar conclusion about maturity/ matriculation examinations. A review of the objectives of these examinations indicates that they test the ability of students to apply the knowledge they received in a “mature” manner. Secondary-school leaving examinations, on the other hand, deal with proficiency in the subject matter taught in secondary school.

The West African School Certificate Examination (as given in Nigeria), for example, is a school-leaving examination. What is being tested is the work completed in secondary school. Aside from a consideration of the level of coursework (an irrelevant point here), the Italian maturita is an excellent example of an examination that deals with students’ intellectual maturity, that is, it tests their ability to synthesize, extrapolate, interpolate and apply already-acquired knowledge, with no new subject matter being introduced.

A third, and perhaps more widespread, way to deal with the issue is to say that we should look at foreign secondary-school systems and grant credit for “advanced level” coursework completed with good grades. If we apply the standard of evenhandedness, and U.S. students are granted the same privilege, then this is fair as long as a careful review of a syllabus has been made. If institutional policy is to never grant credit for secondary-school work unless it is certified by some formal, external examination, such as AP or CLEP, then one must be able to justify the inconsistency. If one grants only course-equivalent credit for domestic transfer students, then doing otherwise for foreign students needs to be justified. Two common cases of possible credit for U.S. high school graduates are six yeas of Latin taken at U.S. parochial schools, and Calculus taken as part of a continuous high school mathematics curriculum. Whether we like it or not, most U.S. collegiate institutions, when dealing with external work, do not even attempt to certify what a person knows, but first try to ascertain at what academic level the work was taken, and then determine the acceptability and applicability of that work to the curriculum. Even if a modest degree of consistency is to be sought, we must understand the impact of our decisions. The most frequently used resources on foreign educational systems propose placement recommendations based upon the tacit, if inadvertent, assumption that an exemption from institutional policy exists for foreign credential evaluation, as each recommendation assumes the ability of the evaluator to apply unique standards to the foreign evaluation.

Dealing with these issues, and coming to decisions about how to synthesize diverging positions, will lead the evaluator to a consistent and defensible approach.

In order to assess foreign education for transfer credit properly, the credential evaluator must understand institutional practices. There are three separate evaluations that can be made in this assessment: course credit value; grading; and the establishment of equivalencies.

Course Credit Value

Defining a semester hour is integral to a proper evaluation. A semester hour is defined as one 50-minute period of lecture or recitation for duration of 15 weeks, totaling 750 minutes a term per credit. Laboratory and practicum work is often quantified as two, three, or four such 50-minute hours for each credit.

When dealing with systems that provide this information, decision-making, is relatively easy. Exceptions or difficulties may arise when a system provides many classroom hours per week that would result in a great deal of credit if the straight arithmetic formula is applied. Generally, this is due to a quantification of student study responsibility different from that used in the United States. In giving orientation to new students, we often tell them that for each hour of lecture or recitation spent in class, approximately two hours of preparation are necessary. Thus, a student in the United States who takes 12 credits is expected to spend about 30 hours per week in preparation for a total time commitment of 45 hours per week.

In systems where the hours noted on academic documents appear excessive, it probably is true that much less time outside of class is required. Whether because library collections are limited or books are unavailable in the language of instruction, there usually is an explanation for the additional classroom hours spent each week. One way to deal with this is always to apply your institution’s maximum term credit load for the highest number of credits allowed and never exceed this for any given semester’s transfer credit. Also apply the average semester credit load (usually the total number of credits required for a bachelor’s degree divided by eight—the number of semesters in which a full-time student “normally” obtains a degree). Thus, for a 120-credit bachelor’s degree program, the average semester load would be 15 credits while for a 128-credit program, it would be 16 credits. By using these two guidelines, the number of total credits granted will be rational for your own institution.

For example, a student from a Taiwanese university presents a transcript that indicates 24 credits were completed in a semester. If you apply your institution’s maximum semester credit hours, let us say 18, you would allow only 18 of the 24 credits in transfer. Whether you discount eight credits, or apply a percentage factor to each credit, depends on your institution’s policies. The application of a percentage factor should not be determined by a single semester’s credits but rather upon a calculation based on the total credits required for the degree in your institution, divided by the number of credits the foreign institution requires. Again, using Taiwan, in a four-year bachelor’s program, 160 credits may be required for the degree, while U.S. institution “A” requires 120. 120/160 = 75%. Thus, .75 becomes the number by which the Taiwanese credits are multiplied in order to arrive at “U.S.—like” credits. The 24 credits discussed above, when multiplied by the .75 factor, reduce to 18 semester credits. If your institution has a maximum semester credit load of 17, you would have to consider denying one additional credit.

When the process is complicated further when either the number of hours indicated for each course in undifferentiated as to lecture and recitation on the one hand, and laboratory or practicum on the other; or worse, when no hours are given. In the first case, it would be wise to obtain a copy of the syllabus for the courses that usually have laboratory or practicals and to determine whether “preparation time” – usually study periods not normally credited in the United States—are included. In the absence of these data, a good guess within the context of the institutional guidelines above is the best thing you can do.

It can be problematic to obtain a “transcript” that does not contain and indication of hours. This is often true, for example, with the British system. When this occurs, the “average year” concept frequently is applied. Here the assumption is made that a full-time student is a full-time student, regardless of educational system. This is in keeping with the earlier discussion of applying maxima to semester credits based upon institutional standards. If a transcript is received with a notation of five courses being taken for an academic year, this approach would result in the assigning of six semester hours to each course, as a full year would be 30 semester hours. As it is possible that the courses in the foreign system are weighted, such as one meeting twice as frequently as another, this might not be completely accurate. Still, without a syllabus review—a valuable but often impractical, time-consuming process for most admissions officers—this is the best one can do. If an error occurs, to the students’ disadvantage, you will be notified soon enough.

Grading

Once we have established what is transferable in terms of academic level (as discussed in Part I) and a decision has been made as to how many credits it is worth, the next issue to wrestle with is whether the quality of performance is sufficiently high to be eligible for transfer. At the undergraduate level, most U.S. institutions require a grade of “C” (or its foreign equivalent) in order to be transferable.

Three issued come into play here. The first is the determination of whether there is a “D” equivalent grade in a particular education system. Quality concerns beyond this are more related to admissions decision-making rather than to eligibility for the transference of credit. In the U.S. a “C” may be defined as a quality level minimally required to obtain a degree, but not the lowest passing grade. When viewing foreign systems, we frequently find that the lowest passing grade is also minimum grade average required to graduate—there are no lower passing grades. An attempt to determine the “C” equivalent by ascertaining grade distribution may not be valid, therefore, as many educational systems do not use the upper end of the grading scale, except in rare circumstances. It is believed that the intent of the U.S. system is that the “C” represents the grade average required to meet the standards for graduation. Therefore, this criterion should be applied to foreign systems, both for the determination of eligibility for transfer credit and for the calculation of a grade point average. You should not be troubled by the fact that a system does not have a “D” equivalent.

Clearly, there is no easy answer but the review of syllabi coupled with student interviews would serve all parties best. As a fallback, the assignment of elective credit, at least initially, would allow the student to commence study with a fairly good idea of the length of time required to obtain the degree. Specific course equivalent evaluation, then, could be limited to those subjects for which evaluations must be completed – major or minor, or general education requirements.

The complexities of the foreign transfer evaluation process are obvious and are exacerbated by inability, at times, to come up with a rational response to a problem. You must be clear about what it is you are certifying—what students know or where they learned it, or a combination of both. While using equality of treatment as a yardstick, you have to maintain a position of flexibility, especially in situations where there are no applicable guidelines available. Be willing to try some new ways of dealing with the problems.

However, as the bottom line in transfer evaluation is its academic nature, always involve faculty in the decision-making process. You can gain the confidence of faculty by such inclusion, enhanced by having an academically valid reason for every decision you make. A good way to look at the process is to divide it into two distinct areas: administrative decision-making (academic level, quality level, number of credits) and academic decision-making (course equivalencies, waivers of requirements). By mediating these processes through institutional policies and practices and by maintaining a flexible stance with respect to potential anomalies, both your institution and its student body will be well served.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).