By Paul Schulmann, Research Manager, WES

The Institute of International Education (IIE) released its 2017 Open Doors Report on International Educational Exchange [1] on Monday. It confirmed what many in the U.S. international higher education community feared: a decline in new international enrollments.

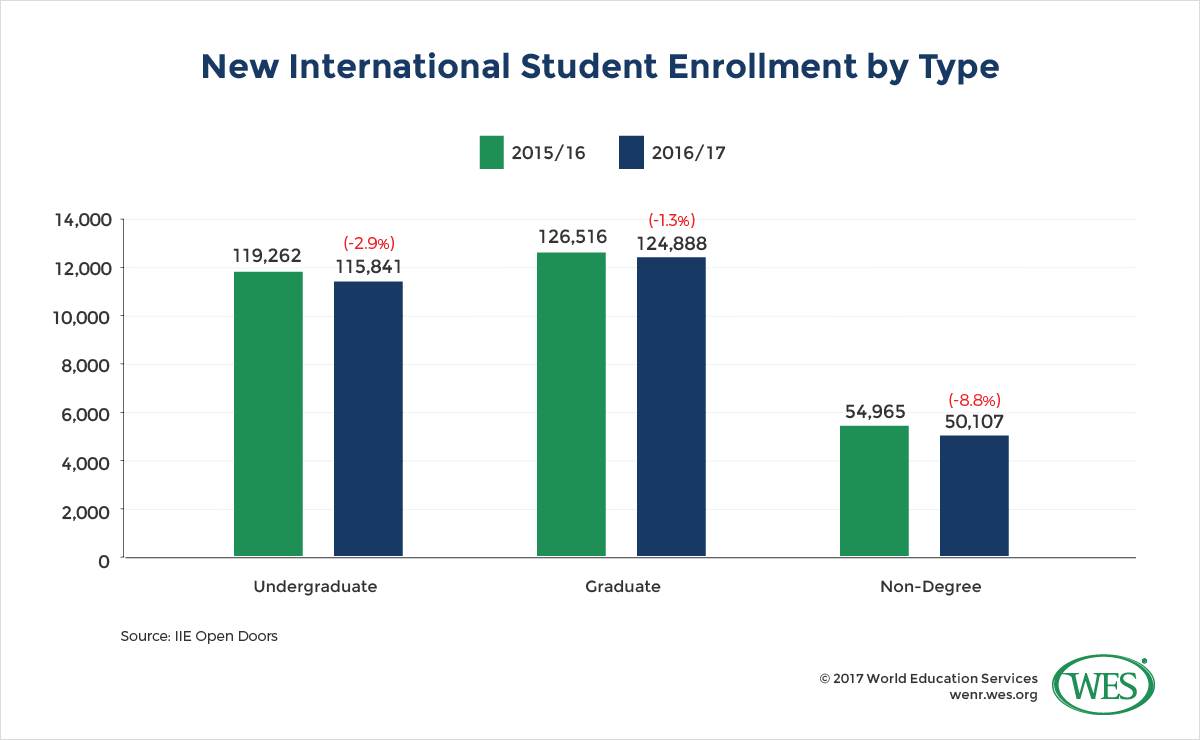

While the total number of international students in the U.S. increased by 3.4 percent for the 2016/2017 academic year, new international enrollments decreased by 3.3 percent.

Institutions, in other words, are not replacing students who graduate. A separate survey by IIE [2], which included fewer institutions and sought to uncover trends at the start of the 2017/18 academic year, seems to confirm this finding. This second survey found that new international enrollment declined on average 7 percent for fall 2017.

What Happened

The U.S. Political Environment and Changes to Visa Policies

Together, these findings paint a vivid portrait of how sensitive student flows are to a number of local and global phenomena. U.S. policies effecting international student and labor mobility have implications for prospective and enrolled international students. The consequences of increased visa scrutiny and the travel bans factor into the 7 percent decline reported for this fall, as does pervasive anti-immigration discourse.

Uncertainty regarding the future status of many visa classes has had an especially chilling effect on prospective international students. In IIE’s Fall 2017 International Student Enrollment Hot Topics Survey [2], visa problems, including application process issues or delays/denials, is the top reason cited for enrollment declines at 68.4 percent, up from 33.8 percent the previous year. Notably, 56.8 percent of institutions surveyed cite the U.S. social and political environment as a factor for declining enrollment, the third most cited reason.

In India, the second largest source of international students to the U.S., changes to U.S. visa policies and concerning news about the Indian diaspora, particularly this year’s shooting of two Indian immigrants in Kansas, are widely reported in the media. In a recent IIE report [3], 80 percent of institutions said that safety is a pronounced concern for Indian students. While Indian enrollment for 2016/17 grew 12.3 percent from the year prior, the bulk of the increase [4] comes from students on optional practical training (OPT), which increased 35 percent, suggesting that new Indian enrollment for degree programs grew at most 4.7 percent.1 [5]

It’s also worth noting that Monday’s Open Doors report uncovered widely divergent trends on new enrollments in OPT, and new enrollments in other degree and non-degree programs:

- Undergraduate enrollments dipped 2.9 percent.

- Graduate enrollments decreased by 1.3 percent.

- Non-degree enrollments fell by 8.8 percent.

- Participation in Optional Practical Training (OPT) [6] increased 19.1 percent to 175,694 students.

- Enrollments in Intensive English Programs plummeted 25.9 percent.

This rise in OPT was likely driven by a 2016 extension to the time that STEM students are allowed to stay in the U.S. and work, and accounts, at least partially, for the 3.4 percent increase in total 2016/17 enrollments. The fact that the extension could be undone by executive decree should give further pause to anyone following the latest news about international students’ interest in study in the United States.

Reduction of Scholarships and Other Financing Challenges

While the American political climate undoubtedly impacts international student mobility into the U.S., declining enrollment is attributable to other factors as well.

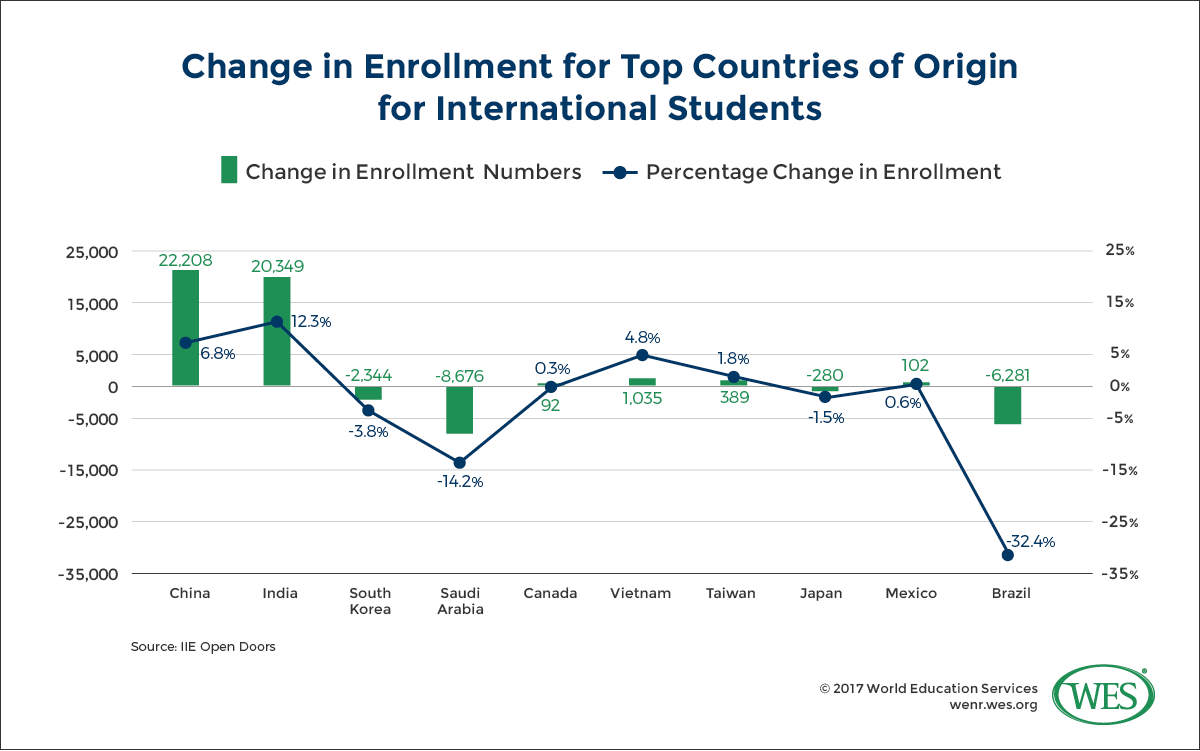

The news from two countries makes this point: Total enrollments from Brazil plummeted a staggering 32.4 percent; Saudi Arabian enrollments sunk 14.2 percent. These steep declines are largely due to cuts to international scholarships in those countries, notably, the Brazil Scientific Mobility Program and the King Abdullah Scholarship Program.

“This is the first year we see a clear reliance on the scholarship programs that have driven the growth over the past several years in the U.S.”, says Rajika Bhandari, head of research, policy, and practice at IIE. “A lot of the growth beyond China [in recent years] has been from Saudi Arabia and Brazil—we now see the impact of this reliance on the U.S. higher education sector.” [8]

[8]

Brazil was also in the midst of political and economic crises last year, and experienced a 3.6 percent contraction in GDP [9] according to the World Bank. This drop has significantly impacted students’ ability to pursue an education in the U.S.

“Education is a big investment,” says Raymond Lutzky, senior director of enrollment and admissions at Cornell Tech. “Even the affluent of Brazil were concerned about the liquidity of their cash, and people don’t make expensive long-term investments in a volatile economy.”

Competition from Abroad Heats Up

The declines are also attributable to increased competition for international students from other countries, some of which have managed to triangulate government policy and university efforts into comprehensive and effective internationalization strategies.

“We’ve seen countries such as Canada increase their internationalization efforts,” remarks Bhandari. “We also see countries offering more and more programs in English at lower costs.” (In September, ICEF Monitor [10] reported that “the number of English-medium undergraduate degree programs in Europe has gone from practically zero in 2009 to nearly 3,000 this year.”)

IIE’s Fall 2017 International Student Enrollment Hot Topics Survey [2] found a 36% increase in survey respondents reporting students enrolling in another country’s institutions as a reason for declining enrollment.

Australia is an example of a country that has thoroughly developed its international higher education infrastructure. In 2016, the government of Australia released a National Strategy for International Education 2025 [11], which highlighted the importance of international education and provided resources and a roadmap to advance it. These actions—as well as the collective efforts of individual institutions—have paid off. In August 2017, international enrollment at Australian universities reached 338,399 [12], up 15 percent from August 2016. Incredibly, one quarter [13] of all Australian higher education students are international.

Similarly, China [14], the largest country of origin for internationally mobile students, has embarked on an ambitious effort to become a major hub for international education. China’s vision of becoming host to half a million international students by 2020 was first articulated in 2012. Since this pronouncement, China has surpassed 400,000 international students and is now the third largest host [15] of foreign students.

This impressive development is illustrative of an interesting dynamic in international student flows: Economies often develop faster than HEIs’ capacity to meet a growing demand for quality higher education. As economies advance, their higher education systems develop, and become both increasingly attractive to international students and capable of meeting domestic demand. This dynamic will have a large impact on the future of flow of international students.

In fact, countries all over the world are proactively implementing strategies to increase the enrollment of international students at both the institutional and governmental level. Increased work and visa opportunities, the immense proliferation of English-taught programs [10] and other more individualized efforts effectively challenges the U.S.’s role as the top recipient of international students. According to Project Atlas, the share of international students hosted by the U.S. decreased from 28 percent to 24 percent from 2001 in 2017.

While many countries are moving in the direction of harmonizing public policies and working with HEIs to create a strong internationalization framework, U.S. HEIs are typically left to their own devices. The lack of an overarching national policy framework and agenda is particularly challenging for schools as the threat of declining domestic enrollments [17] creates a sense of urgency with regards to international student enrollment. Policies that limit visa access for certain countries, complicate the visa process, or restrict labor mobility or access to the labor market, will make international recruitment more challenging.

Going Forward

While those invested in the movement of students across borders would like to see the numbers continually increase, student mobility is shaped by the interaction of complex factors, and is prone to fluctuation. The current decrease in international enrollment speaks to the need for institutions to develop strategies that are responsive and prepared for change. It remains unclear based on the data whether the U.S. has gone from a golden age of enrolling international students to its twilight years.

Currently, half of international students come from China or India. In 2016/17, Chinese and Indian enrollments grew by 6.8 percent and 12.3 percent, respectively. Major declines from either country will send shockwaves to higher education institutions (HEIs) reliant on them.

It is thus imperative for institutions to diversify their international enrollment funnel. Kirsten Feddersen, associate vice president of international programs at Southern New Hampshire University cautions, “Relying on a few enrollment funnels is typically not a good approach. Like a financial investment, you don’t want to put all of your eggs in one basket, both to ensure diversity on campus and to avoid a drop in enrollment if a funnel collapses.”

She goes on to describe her own institutions approach to diversification:. “We try to broaden our recruitment efforts to create a solid number of sustainable funnels so that if one market collapses it will lower the impact on our overall enrollments,” she says. “We allocate a certain percent of our budget towards markets where we haven’t been before. The ROI is uncertain. We divide our budget into these exploratory markets, markets we are confident will develop within a couple years, and then we allocate at least 50 percent to traditional markets with solid yield potential.”

Raymond Lutzky of Cornell Tech advises institutions to remain optimistic and seek opportunities during a challenging period for international recruitment. “Those institutions that invest now as others are flying away will see benefits when enrollment stabilizes. Building personal connections and brand awareness is paramount to success.”

It is also important to note that there remain challenges that impede university systems outside the U.S. from absorbing international students en masse. The limited number of available seats and campuses in other destination countries, for instance, acts as one natural brake on capacity. “We should keep in mind that there are far fewer institutions in Canada and Australia,” says Bhandari, even as she discusses the “considerable growth in enrollments” in both countries.

While the short term trends portend a challenging period for international student recruitment, U.S. universities are still renowned for their quality as well as the diversity of programs they offer. This will continue to drive interest in a U.S. higher education. While U.S. HEIs are in the midst of a tumultuous period for international enrollment, those that adapt and innovate will be able to weather the storm.

1. [18] Number calculated from increase in total graduate and undergraduate enrollment from 2015/16 to 2016/17 from India. Analysis excludes those in non-degree programs and on OPT.