Ross Jennings, Senior Director, International Education, International Programs, and Extended Learning, Green River College

China presents a major challenge for lower- or unranked American colleges and universities. It is, in many ways, a Gucci [2] country: Name brands, whether they relate to handbags, cars – or overseas universities, are huge.

Consider the book “Harvard Girl [3].”

In 2000, it took China by storm. It was the story of how a Chinese girl, Liu Yiting, trained virtually from birth to get into Harvard. Her highly touted success both reflected and exacerbated the Chinese mania for trying, at least, to get into a luxury brand university.

The story wasn’t apocryphal. Students from China are, more than any other group, interested in a school or program’s reputation. But smaller and unranked institutions are right to hold out hope that they, too, can attract students. The huge number of students now studying abroad still represents the tip of a huge iceberg in China – one which extends to all sizes of cities and towns in the country.

Brand Name, Family Status, and City Tiers

China’s brand name mania is nowhere more evident than in its most commonly recognized “Tier I [4]” cities – global hubs like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen. In these cities, getting children into top US universities can become an obsession [5]. Test prep schools [6] and educational advisory agencies in these urban hubs make a fortune [7] preparing students for admission to top universities, either through helping them improve their scores on standardized tests like SAT, GRE and TOEFL, or, in a darker side of the business, by manufacturing documents to help them obtain admissions [8] regardless of their actual qualifications.

Tier II cities like Chengdu, Tianjin and Nanjing are not much different from Tier I cities. These Tier II cities are often located near Tier I hubs like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. They tend to attract increasing numbers of young skilled professionals who are seeking a better quality of life than they can achieve in China’s congested megacities. Most Tier II cities are on the verge of achieving – if they have not already – first tier status. These cities can be every bit as difficult a recruitment environment as Tier I cities.

Cities like Hefei, Qingdao, and Harbin, however, fall into the third tier. They, like some Tier IV or “non-tier” cities, may be an interesting option for lower ranked American institutions. In these cities, many people can afford to study abroad, but they have more balanced expectations of which schools they might get into, and a far broader assessment of which schools may be worthwhile.

City “ Tiers” and China’s Rising Middle Class: A Definition in Flux

The first step in understanding how to tackle recruitment in Tier III cities is to develop an understanding of what criteria are at play in rankings.

China analysts typically rely on a tiered classification system to better understand economic developments, consumer behavior, and demographic developments among the country’s more than 600 cities. Categorization is based on factors such as gross domestic product (GDP), population, and level of political administration. According to the South China Morning Post:

- Tier I cities have a GDP over USD $300 billion, are directly controlled by China’s central government, and are home to more than 15 million people.

- Tier II cities have a GDP between USD $68 billion and USD $299 billion. They are provincial capital or sub-provincial capital cities; and they have populations of three to 15 million.

- Tier III cities have a GDP between USD $18 billion and USD $67 billion; they are prefecture capital cities; and they have between 150,000 and 3 million people.

- Tier IV cities have a GDP below USD $ 17 billion; they are county-level cities; and they have fewer than 150,000 residents.

These definitions and categories are informal, the parameters often overlap, and there is no general consensus about which city falls into which tier: Different analysts may credibly categorize the same cities in different tiers.

Moreover, beyond the big four in the first tier, city rankings are not static. This is due in no small part to the rise of the middle class in China, and to its increasing reach into Tier II and III cities. According to Gordon Orr [10], the former Asia chairman at global management consulting firm McKinsey & Company:

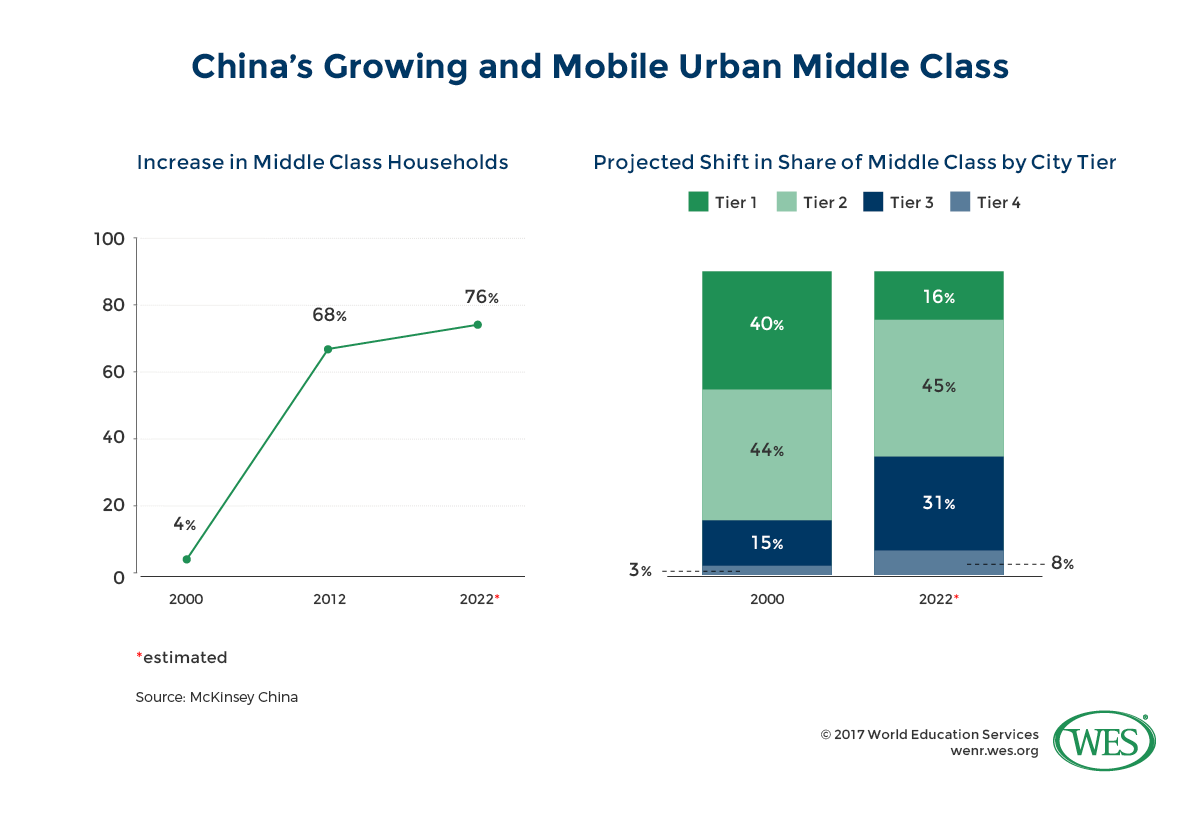

“As recently as 2000, only 4 percent of urban households in China was middle class; by 2012, that share had soared to 68 percent. …[By 2022], China’s middle class could number 630 million – that is, 76 percent of urban Chinese households and 45 percent of the entire population…

In 2002, 40 percent of China’s urban middle class lived in the Tier I megacities of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen. However, this share is expected to decline to 16 percent in 2022, while the share will rise in Tier II and Tier III cities. Tier III cities hosted only 15 percent of China’s middle class households in 2002; by 2022, that share should reach 31 percent.”

Fungible though the rankings are, the framework is useful when developing recruitment plans that go beyond the usual suspects.

Small College Success in China: The Green River College Case Study

Lesser- or unranked institutions can often recruit successfully in smaller cities that have not yet emerged into Tiers I or II. That said, competition even in such cities can be surprisingly strong. The low hanging fruit was harvested long ago. Moreover, there’s no real playbook for success. There are, however, lessons to be learned from others who have gone before. Green River College offers an interesting case study.

Green River is a two-year community college in in Auburn, WA with an enrollment of about 8,000. The college has successfully recruited Chinese students for the last ten years. As of fall 2017, Green River hosted 1,600 international students, 620 of them from China. Recruitment has been most successful in smaller cities such as Zhuhai, Yantai, and Hefei.

The school’s recruitment success in China is highly relevant for other small or unranked institutions. The school faces a double challenge in terms of recruitment in China. Not only is it not ranked; it is not a university at all. Instead, it is a community college – a classification that does not inspire confidence among Chinese parents. The closest analogy in China is “dazhuan,” a three-year technical college that students often attend if they cannot get into a good university.

However, Green River has managed to overcome this perception, largely by offering students from China a compelling package developed by paying close attention to the needs of the market and to the needs of individual students:

- An alternate route to top institutions: As soon as Green River set its sights on recruitment in China, it was clear the school could not recruit head to head with the likes of Southern Cal, Wisconsin, and Purdue. Instead, the college sought to position itself as one step along the way to a degree from these and other top ranked institutions. Administrators reverse-engineered transfer pathways to these and other ranked universities all over the U.S. The goal was to make sure that interested international students, even those who did not obtain immediate admission, could get in once they had filled specific requirements. The effort paid off. Green River Chinese graduates regularly transfer to top universities like Washington, Michigan, Illinois, and UCLA. Over about the last 10 years, Green River has transferred 41 Chinese students to Illinois, 8 to Michigan, 25 to UCLA, and 70 to Washington. (It has also transferred many more from other countries). Other Washington institutions such as Seattle University (34 Chinese students), and Washington State (48) are popular transfer destinations, as are Big Ten universities like Indiana (148, mostly at Carey School of Business), Ohio State (55), Minnesota (32), and Purdue (23).

- Relationships: Green River has spent a decade building strong relationships with a core group of educational advisory agents and school officials in China. Supported by frequent visits from Green River international programs staff, these people can credibly act as the voice of the college when speaking to parents and students. Green River’s agency relationships exist in big cities and small, but its programs with local schools and universities developed best in Tier III cities (Hefei) or even smaller ones (Zhuhai, Luoyang, Yantai).

- Comprehensive support: The college provides international students with an all-encompassing set of services, from academic and personal advising to guaranteed housing. The college seeks to help students develop close relationships with the local host families who house them and college instructors who teach them. The goal is to increase student academic success, and ease the transition from abroad to a highly localized setting.

A few small U.S. higher education institutions have established very strong programs in China, in part by focusing on recruitment in tier 3 cities. Two examples shed light on other ways to approach these cities:

- Fort Hays State University is a small Kansas institution that has developed an extensive international program. The school has an enrollment of roughly 14,000 students. The institution has established a 2+2 dual-degree program in China, with instruction delivered locally by Fort Hays professors, qualified local instructors, online instruction, or a combination thereof. More than 3,000 Hays students have enrolled at two Chinese universities alone. Fort Hays has 47 partner universities worldwide. Of its 20 Chinese partners, 15 are located in tier 3 cities or smaller. According to Open Doors 2016, Fort Hays home campus hosts some 430 international students.

- Keuka College in update New York has dual-degree programs in four universities in China. Three are in tier 3 cities or smaller. The college’s website states that it is serving 2,700 Chinese students at its four partner institutions in China, an enrollment larger than it hosts at its home campus in New York. Keuka’s website indicates a home campus enrollment of just under 2,000, including, according to Open Doors 2016, 47 international students.

Insights and Take-Aways

- Student well-being and success are critical. Student welfare is the beating heart of any educational program, international or otherwise. The success of its students as individuals should be the primary focus of any educational institution or program. It is essential to prepare in advance for the needs of a new cohort of students before launching a campaign to recruit them. This does not always happen. Institutions new to international recruitment in particular must be well-prepared to serve a new group of students whose requirements will differ considerably from domestic students. This will include language support for non-native English speakers, whose high test scores in TOEFL or IELTS may belie weak “active” skills in oral and written English.

- Chinese Tier III and smaller cities are a big market for international education. This has not always been the case. Green River first tried to recruit in the smaller Jiangsu city of Yangzhou in 1994 – utterly without success. Today, the college has 17 students from that city, with eight more on the way. In the fall of 2017, 60 percent of Green River’s Chinese transfer graduates were from Tier III or smaller hometowns. (The fact that 40 percent of them have come from Tier I or II cities should also give smaller schools reason for hope: With the right programs in place, small and unranked schools can make headway in major cities, too.)

- Nothing is easy in China. China represents a very well-developed and sophisticated market for international education. Competition is increasing all the time, not least from Chinese institutions themselves. Another major new competitor is pathway programs – companies like Into and Navitas – that recruit thousands of students for their mid-major partner schools like Auburn and Oregon State. They pay commissions to agents that many institutions, particularly low-tuition community colleges, cannot come close to matching. Like factory trawlers sweeping the ocean of fish, they recruit many students that might have otherwise gone to smaller universities and colleges.

- Partnerships are critical. Relationships take time to develop and many personal touch points to maintain. They are also rarely exclusive – for agents, schools, parents or students. A recruiter may bask in the afterglow of a great meeting or recruitment fair, only to find out that the same partner, agent, or student is going to another meeting or fair the next day. Developing productive partnerships takes effort, determination, and time. Agents have many suitors, so training, support and attention must be provided frequently.

Recruiting Chinese students for lower or unranked American colleges and universities is not for the faint of heart. But less prestigious institutions can be very successful in marketing in third and lower tier Chinese cities where there are fewer expectations of everyone getting into Harvard or Cal Berkeley. Just as important as marketing, though, is the sustainability of recruitment efforts – and that hinges ultimately on the well-being and success of the students.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).