Hanna Park, Senior Manager of Training, WES, and Ashley Craddock, Editor, WENR

This article examines the roots and scope of the diploma mill problem, the damage they do to individuals, institutions, and society, and, most importantly, the solutions that can be brought to bear against them.

Diploma mills are a chronic problem in both higher and secondary education. Particularly in the digital age, they operate in the shadows, setting up business operations in one country, and offering “degrees” for a price through multiple, cleverly packaged websites. At a moment in history when online education is widely accepted and the acquisition of credentials often piecemeal, they are sometimes hard to recognize, especially for potential students hoping to get a leg up in the job market.

Consider the roughly 98 million people in America who qualify as “post-traditional learners” according to a 2017 “manifesto” by the American Council on Education (ACE) [2]. Nearly 31 million are, says ACE, “at the doorstep of a credential” with “one year of college or more [but] no degree to show for it.” Many have attended and earned credits from a patchwork of institutions, only to be thwarted by the challenges of balancing the demands of family and work life. Many are from economically vulnerable backgrounds. Some are immigrants, others the children of immigrants. They tend, says ACE, to “attend less well-resourced, open access institutions.” Given the wage premium attached to even an associate degree – an estimated USD$ 3,100 a year in after-tax earnings – these post-traditional learners are often motivated to seek career-oriented credentials.

This combination of characteristics and motivations makes these degree-seekers, as a group, particularly vulnerable to the come-ons of the shady operators of degree or diploma mills. They are not alone, and the problem of diploma mills is not solely an American one: Other individuals vulnerable to the mills’ pitch are “students and parents in developing countries, [who are] attracted by the opportunity of a foreign and more portable degree [3],” says Judith S. Eaton, president of the Council for Higher Education Accreditation, and Stamenka Uvalic-Trumbic of UNESCO’s Division of Higher Education.

Granted: Not all “graduates” are dupes of shady purveyors of false credentials. Some are explicitly seeking unfair shortcuts to career advancement and higher earnings.

Bogus Degrees in the U.S.: The Earnings Premium and the Impact on the Workplace

Diploma mills prey both prey on vulnerable individuals, and allow those who are unscrupulous to shinny their way unfairly up the career ladder. On average, master’s degree holders earn 45 percent more than graduates of a bachelor’s program. In general, it takes one to two years to complete a master’s degree from one of the regionally accredited institutions in the United States. However, by going through a diploma mill, a person can obtain a Master of Business Administration in the 30 minutes it takes to fill out a short form containing the applicant’s intended major, graduation year, applicable “life” experiences, and credit card information. Based on the bogus master’s degree, he now qualifies for a raise and possible career advancement. If the employer accepts the bogus degree at face value, it not only unfairly advantages the holder of the fraudulent degree, it also eats away at the other employees’ rationale for devoting time and effort toward legitimate degrees.

Wicked Problems

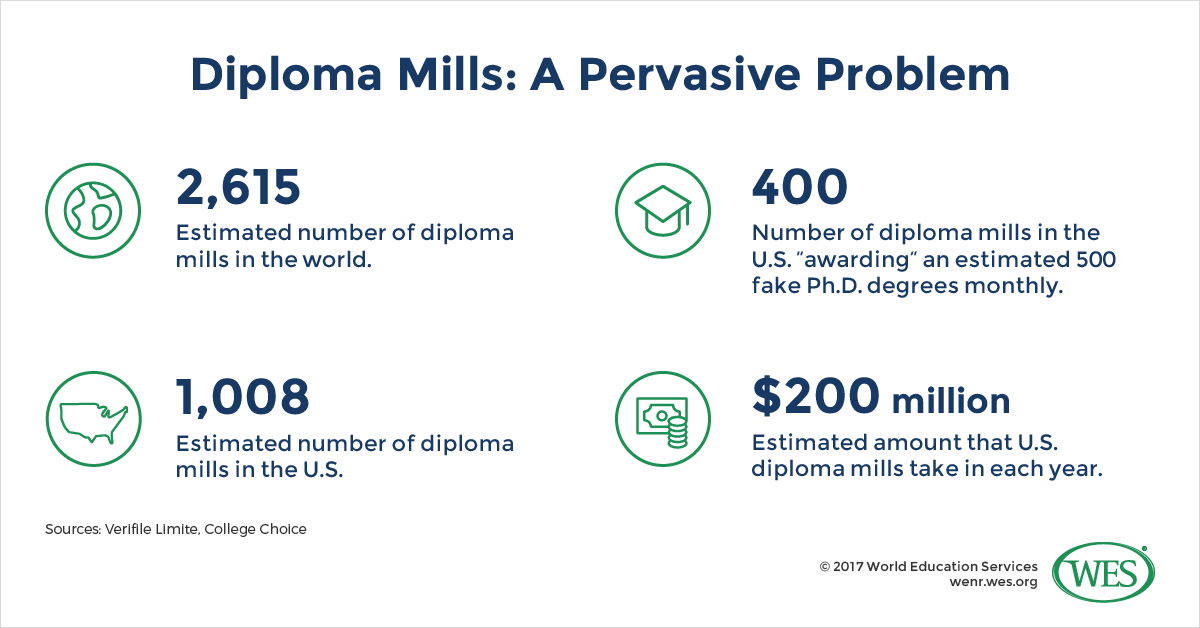

Experts believe that there are more than 2,600 diploma mills in operation globally, and more than 1,000 in the United States [4]. An estimated 400 of those in the U.S. award fake PhDs. The August 2017 sentencing [5] of Pakistani national and Axact [6] executive Umair Hamid to 21 months in prison and a USD $5.3 million fine was a high-profile but rare instance of the international operators of a diploma mill being brought to justice.

In most cases, diploma mills are hard to root out, despite the attentions of UNESCO [7], the U.S. Department of Education, the FBI, the Federal Trade Commission, education ministries the world over, and a slough of other watchdogs. Why?

Once mom and pop shops, diploma mills are now multi-dimensional, transnational operations. They thus represent a classically wicked problem [8], with broad ranging, society-wide impacts. By their nature, such wicked problems defy one simple solution by one single actor. Diploma mills and their equally wicked brethren, accreditation mills, fit this criteria. They are:

- Global in nature, and often highly localized in impact

- Jurisdictionally slippery, hard to count, and harder to police

- Fueled by seemingly insatiable demand, especially among workers who must provide documentary evidence of qualification in order to find jobs that pay anything but a subsistence wage

- Designed to dupe individuals, and defraud employers

They are also difficult to identify in part because definitions of diploma mills are inconsistent [9]. In a world of legitimate online learning and for-profit operators of varying degrees of quality and legitimacy, defining (and thus prosecuting) what is and what isn’t a diploma mill can be oddly difficult.

However, inaction isn’t really an option, despite the intractable nature of the problem. Diploma mills are big, black-market businesses enabled by the same digital technologies that have fueled globalization more generally. The dollars directly at stake are in the tens and hundreds of millions, but the costs to reputable higher education institutions – in terms of degradation of the value of legitimate qualifications, and erosion of the brand equity and market share – are incalculably higher.

Anyone who cares about consumer protections, the integrity of higher education, or about the ability to vet applicants’ qualifications for the positions they’re seeking has little choice but to try to squelch mills and minimize their impact.

Diploma Mills: Defining Them and Understanding How They Flourish

Also referred to as degree mills or bogus institutions, diploma mills (and the equally fraudulent accreditation mills that purport to oversee them) thrive on loopholes.

Consider the United States: The country lacks centralized national oversight of universities. Instead, every state has its own rules when it comes to regulating education-related matters. Couple this lack of centralized oversight with the voluntary nature of accreditation, and it’s easy to see just how vulnerable the system is. And although the country’s Federal Trade Commission [10] (FTC) has regulated the use of the word “accredited” since 1998, many unaccredited operators continue to use the term. Others skirt the issue and advertise their wares – a.k.a., degrees – using the term ‘legal’ rather than accredited.

The FTC, which is tasked with consumer protection and the elimination and prevention of anticompetitive business practices in the United States, has for years actively sought to police diploma mills, which it defines, quite simply, as “[companies] that [offer] ‘degrees’ for a flat fee in a short amount of time and [that require] little to no coursework.”

Even countries with centralized education authorities – e.g. almost every country other than the United States – have had similarly little luck in policing diploma or accreditation mills. The government bodies that oversee education and the designated organizations that handle accreditation have no mechanism for dealing with the most common model of bogus institution: One that claims to be located in one country, but that actually operates from another country.

In this model, an institution might claim to issue an American degree. However, its IP address originates from an island in Pacific Ocean. The physical address of the operation, meanwhile, may well be in yet another country (if it can be determined at all). In such cases, lack of clear jurisdictional authority often results in lack of action against the mill.

Who Buys Fake Diplomas?

Granted: Some people purchase knowingly purchase counterfeit or fraudulent degrees by design. Others – many of them either the post-traditional students described by ACE, or students with little knowledge of the education system – are clearly duped. On the latter front, the December 2016 complaint against convicted Axact vice president Umair Hamid is particularly telling. It describes the interaction between one student, his parents, and an Axact diploma mill called “Belford”:

- In or about 2006, Consumer-1 was interested in participating in an online high school diploma program at night because Consumer-1 worked during the day. After conducting an internet search, Consumer-1 found a website for an online school called “Belford,” which appeared to Consumer-1 to be a real school.

- Consumer-1 was interested in obtaining a high school diploma because a high school diploma was necessary to attend the colleges that Consumer-1 was interested in attending. Purported representatives of Belford made representations to Consumer-1 that Belford was accredited, that the colleges Consumer-1 was interested in attending would accept a high school degree from Belford, and that Consumer-1’s tuition fee would be used to enroll Consumer-1 in Belford coursework.

- Consumer-1’s mother spoke to a representative of Belford by phone, and this Belford representative informed Consumer-1’s mother that Belford was accredited.

- In order to enroll in Belford, Consumer-1 took an online test to determine if Consumer-1 was eligible to attend the school. Consumer-1’s mother submitted the completed exam along with a $300 up-front payment on Consumer-1’s behalf to Belford.

- Approximately two to three weeks after taking the exam, Consumer-1 received a package from Belford containing various documents, including-a diploma. Consumer-1 was never enrolled in any Belford classes or courses.

- Consumer-1 believed that Consumer-1 had earned a high school diploma after receiving the package… Consumer-1’s family went out to dinner to celebrate.[1]UNITED STATES OF AMERICA – v. – UMAIR HAMID, SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK, Case: 2:16-mj-02564-CJS Doc #: 1 Filed: 12/20/16

Accreditation

Accreditation mills add another layer of complexity to the picture. Often operated by the same companies that manage bogus institutions, accreditation mills – whose locations are equally hard to identify – exist for two reasons only:

- To provide bogus entities with bogus accreditation

- To create the potential for additional revenues for their operators

In the face of these layers of complexity, what can be done?

We’ve outlined nine strategies that can be enacted across different segments of society, from the front lines of credential evaluation offices to the court systems to statehouses. Together, these actors have the ability to mitigate the impact of diploma mills.

Some basic strategies:

1. Learn to Spot Red Flags

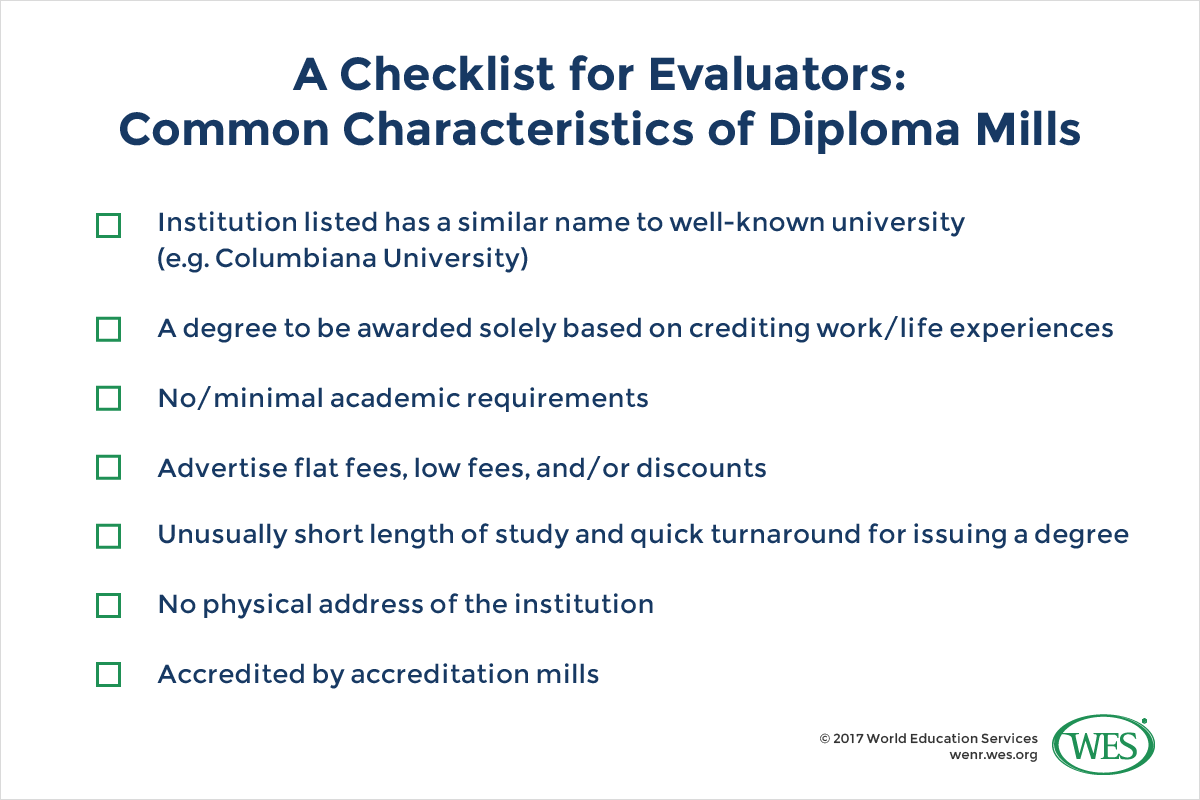

The first level of triage has to be done by those actually reviewing the credentials in question. At universities and colleges, the burden falls on credential evaluators. Among employers, human resources personnel are responsible. In order to avoid hiring employees or admitting students with bogus degrees, reviewers in both environments must examine every degree presented for review. Careful scrutiny of documents uncovers some common telltale signs. A quick Google search can help to confirm suspicions.

When reviewing documents, be alert to:

- The name of the institution: Diploma mills often use similar names to well-known universities or have American-like institution names. For example, Columbiana University or Columbus University is not to be mistaken for Columbia University, based in New York City.

- Credit for work/life experiences: Although some countries may allow students to earn credits based on work or life experiences, it is rare for a degree to be awarded solely based on these experiences.

- No/minimal academic requirements: Generally, submission of a resume or a few exchanges of emails with faculty is not sufficient to earn a degree. NOTE: Some diploma mills have begun to add phony curriculum on their websites that require submission of a few short papers to bypass scrutiny.

- Unusually short length of study and quick turnaround for issuing a degree: Generally, it takes about four years to complete and obtain a bachelor’s degree in the United States. Although it is possible to obtain a bachelor’s degree in less than four years, it is abnormal to receive the degree within the short span of a few weeks or days. If an institution promotes guaranteed delivery of the degree within short period time like 24-hours, that is another sign of diploma mill.

- No physical address of the institution: Diploma mills often do not have physical addresses, existing only virtually. While many legitimate institutions offer online courses for degree programs, it is important to distinguish between the two.

- Flat fee/advertise low cost: In the United States, tuition for higher education is usually set by a number of credits rather than a flat fee. It is rare for an institution to advertise its low cost and offer discounts for its programs.

2. Ensure Familiarity with Accreditation Agencies

Looking up information on an institution alone may not be enough to establish an institution as bogus. Given the prevalence of fake accreditation shops – about 1,000 fake agencies [4] in the United States alone, according to some estimates – it is important to know how to determine the legitimacy of unfamiliar agencies.

Governmental sources can be a good starting place:

- In the United States, the Council for Higher Education Accreditation [12] and the Department of Education [13] provide lists of recognized accrediting agencies and institutions. The U.S. Department of Education also suggests [14] that obtaining a reliable external credential evaluation of foreign degrees can be a way to ensure the comparability to a U.S. degree.

- In other nations, the ministry of education or department of education is likely the primary resource for checking accreditation. WES provides a list of country resources [15] that include respective government bodies for accreditation. Some ministries periodically update lists of accredited institutions as well as of diploma mills.

3. Know What .edu Means and What It Does Not

In 2001, the United States Department of Commerce implemented a ruling [16] that only post-secondary institutions accredited by either regional or national accrediting agencies recognized by the U.S. Department of Education could use the .edu domain. Such institutions must also be located, licensed, or chartered in the U.S. However, the regulation grandfathered in all entities that were using .edu prior to the implementation of the rule. According to a 2015 article by George Gollin, a board member of the Council for Higher Education Accreditation and professor of physics at the University of Illinois, “about 2,400 of the approximately 7,000 existing .edu domains belong to organizations that would not qualify for the domain today. One is held by a firehouse. Dozens belong to diploma mills.”

The rule of thumb here is buyer beware: If there is any doubt about a school using the ‘.edu’ domain, try to look up of its website information using tools like the .edu Whois server on EDUCAUSE [17], a nongovernmental organization that has managed the domain for the U.S. Department of Commerce since 2001.

4. Implement Education Campaigns That Protect Vulnerable Students

Public resources to educate consumers about exploitation by degree mills exist – the Council for Higher Education maintains a webpage [18] with extensive links to state resources on legitimate institutions and accreditors, and on mills, but they are not necessarily high profile – this despite the fact that in 2008, then-U.S. President George W. Bush signed a reauthorization of the Higher Education Opportunity Act. The reauthorization included multiple modifications related to diploma mills. One requirement (re-upped in 2013 [19]) was that the U.S. Secretary of Education work across multiple government agencies to “broadly disseminate to the public information, and resources to identify diploma mills.” A public service campaign describing the prevalence, risks, and ways to identify diploma mills could have a significant impact on their reach, at least among unwitting applicants.

5. Employ the Courts to Squelch Operators

Both civil and criminal courts can be brought to bear against diploma mill operators. Brand degradation is another concern. Will applicants recognize the difference between Loyola State University or Loyola University? In 1997, the Illinois Attorney General filed a lawsuit against the former, accusing the executive director of violating the state’s consumer fraud and deceptive practices acts and the Illinois Academic Degree Act, which requires regional accreditation for colleges and universities. In 2015, the Texas attorney general filed a lawsuit against 13 diploma mills targeting high school dropouts in the Dallas-Fort Worth Area. The suit alleged that the schools lured students to their programs with false and misleading statements — like claiming the diplomas would help students get into college or the military. In 2009, plaintiffs filed a class action suit against Belford High School, and Belford University, diploma mills which claimed to be accredited by the International Accreditation Agency for Online Universities and the Universal Council for Online Education Accreditation – also fraudulent entities. In 2012, the defendants were ordered to pay more than $USD 22.7 million to 30,000 plaintiffs.

The Axact lawsuit is another example of successful prosecution. It’s important to recognize the jurisdictional limits of such cases, though. Based in Pakistan, Axact was responsible for what was called the “biggest degree scam in history.” The scam allegedly generated revenues of up to US$ 150 million by selling bogus degrees to customers around the world. After the scandal broke, Pakistan’s government shut down the company and arrested several employees, while the U.S. Attorney’s Office of Southern District of New York in 2017 sentenced Axact’s Vice President to 21 months in prison and ordered him to forfeit about 5 million dollars [20]. However, by 2017, the primary defendant in Pakistan had been acquitted [21], leaving the company – and its ability to continue business as normal – largely untouched [22] at its point of origin.

6. Revamp Criminal Codes to Crack Down on Usage

In some ways, this recommendation flies in the face of those that advocate for policing mill operators rather than consumers, but its is still worth consideration. Not every state in the United States has same standards regarding use of degrees issued by diploma mill. For example, in Texas, using fraudulent degrees to promote business, gain educational admission, or achieve certain other gains is a Class B misdemeanor, which may result in up to six months in a county jail and a fine of no more than $2,000. The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, for instance, publishes a list of “Institutions Whose Degrees are Illegal to Use in Texas [23].” In Kentucky, knowingly using a fraudulent credential to obtain employment is a Class A misdemeanor.

States like California and Hawaii, by contrast, have such lax regulation on these entities that it is common to find a higher number of diploma mills operating in those states than others.

7. Remove Systemic Roadblocks to Credentials Among Students Who Might Otherwise Qualify for Diplomas

Granted that diploma mills cater to many people who knowingly seek a quick route to career advancement and higher pay; they also lure in unsuspecting and even naive clientele. As ACE pointed out in the most recent version of its “Post-traditional Learners Manifesto [24],” “undergraduate education is no longer the domain of a single institution. It is a collaborative effort that often spans multiple academic programs and campuses.” One solution to this challenge is to remove some of the systemic roadblocks that prevent otherwise qualified candidates – those with credits and coursework at multiple institutions over multiple years – from obtaining credentials. ACE advocates for campus leaders to “create common frameworks for lower division courses, [and develop] meta-majors and comprehensive transfer articulation agreements.” The availability of such pathways would likely staunch unwitting participation in the fraudulent system by students who seek a simple – but seemingly missing – way to knit together the various credits and credit hours into a recognizable and verifiable whole.

8. Develop Technical Solutions

Some institutions are exploring and adopting new ways to digitally protect academic records and institutional information. Blockchain, the technology behind bitcoins, is one such example. As described by Edsurge [25], blockchain is “a public list of records, also known as blocks, that are joined together through cryptography. Each record—let’s say, a microcredential—is a time-stamped transaction between the student and institution. Once a record of the credential lives on the blockchain, it can not be altered (e.g. hacked or replicated) by other users without disrupting the entire blockchain system. In theory, that makes the record virtually impossible to remove or disrupt.” Institutions including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, are exploring the applicability of blockchain to the process of credential authentication. If adopted at scale, such technologies would prove a powerful deterrent.

9. Define Terminology

The ability to determine a coherent approach to degree mills at the national and international level starts with shared language. If we cannot agree on what a diploma mill is, we cannot consistently agree to take action – or demand governmental action – when we see one.

Such definitions are difficult: As noted in a joint 2009 statement [26] put out by UNESCO and CHEA, there is no “single, shared international definition of ‘degree mills’ or ‘bogus providers.’ A number of individual countries have established definitions, however, and have also identified key features of these operations that are obvious wherever mills set up service. Description of these features provides a foundation for challenging mills now and in the future and can, over time, lead to a single international definition of these operations.”

In the United States, definitions remain equally uncertain. Coming to agreement on what does and does not qualify as a degree or diploma mill is – especially in a world of sometimes unscrupulous for-profit education providers [27] and non-standardized and sometimes low-quality online offerings [28] proffered even by public school districts – critical to protecting consumers and the perception of educational quality alike.

References

| ↑1 | UNITED STATES OF AMERICA – v. – UMAIR HAMID, SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK, Case: 2:16-mj-02564-CJS Doc #: 1 Filed: 12/20/16 |

|---|