Jing Guan, Evaluation Documentation Specialist at WES, with Bryce Loo, Research Associate at WES, and Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Both a continent and country, Australia has, as a nation, the world’s sixth-largest land mass. The country is entirely surrounded by water, with the Indian and Pacific Oceans on either side. It nonetheless has been characterized by large-scale immigration ever since British colonialization in the 18th century. Although immigration has become an increasingly polarizing political topic in Australia in recent years, the government has continued to embrace favorable immigration policies for highly skilled and educated individuals. It’s strong economy has attracted many. Australia is also one of the world’ top international education destinations, particularly for degree-seeking students.

In 2015, Australia had the third-largest share of foreign-born residents among OECD countries after Switzerland and Luxembourg. Fully 28 percent [3] of the country’s 24 million people were born in another country – a far larger share than in Canada and the United States. While net overseas migration rates have slowed [4] in the past few years, immigration accounted for 60 percent [5] of Australia’s population growth since the mid-2000s, and the percentage of the foreign-born population has increased by almost 4 percent [3] since 2005.

Some of the top countries of origin among the current wave of immigrants include India [6], China, and the United Kingdom. Most of the recent immigrants are relatively young and well-educated: 81 percent [7] of recent migrants arrived at the ages of 20 to 44, and an estimated 65 percent had some form of post-secondary educational attainment, 76 percent of them holding a bachelor’s degree or higher.

More than half of Australia’s voters [8] surveyed in 2017 favored reducing immigration, a fact causing growing numbers of politicians to advocate curbing [9] migration from overseas. Australia has recently instituted increasingly harsh [10] asylum policies [11] and has been criticized by Human Rights Watch and other organizations for detaining so-called “boat people” – refugees and illegal economic migrants crossing over from Indonesia – under inhumane conditions in offshore detention camps [12]. The government of Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull in April 2017 announced that it would also restrict work visas and curb the immigration of skilled workers [13] in 2018. The prime minister declared that Australia would no longer allow “… visas to be passports to jobs that could and should go to Australians. We’re putting jobs first, and we’re putting Australians first [14]”.

It remains to be seen, however, if the current backlash against immigration will decrease admissions of skilled immigrants in the long term. Many experts believe that immigration is necessary to sustain Australia’s economic prosperity. The non-profit advocacy organization “Migration Council of Australia,” for instance, estimated in 2015 [15] that continued immigration would lead to a “60.4 percent increase in the population with a university education” and boost Australia’s GDP by 5.9 percent by 2050. Support for immigration is much higher [8] among the country’s economic and political elites than amongst the general electorate.

Australia’s continued economic dependence on open borders is also reflected by the fact that international education is a core economic sector in Australia. Over the past decades, Australia has become one of the world’s main international education hubs – a development that has turned international education into Australia’s third largest export after iron ore and coal, valued US$ 15.7 billion in 2015/16 [16]. The number of international students enrolled in degree programs alone increased by more than 150 percent between 1999 and 2015, from 117,485 to 294,438 students (UNESCO Institute of Statistics – UIS [17]).

And Australia still has ample room for expansion: according to a recent analysis by Deloitte Access Economics [18] Australia’s education system has the capacity to increase international enrollments by more than 40 percent within the next eight years. Australia may also capitalize on the political volatility in its two biggest competitors in international education – the U.S. and the U.K. – where the have called into question both countries’ commitment to multiculturalism and openness. At the same time, the growing anti-immigrant sentiment in Australia itself poses significant risks to the country’s international education sector, especially if the government should curtail post-study work opportunities – an important draw for international students.

In addition to a attracting a growing share of the world’s international students, Australian universities are also major providers of transnational education (TNE), particularly in Asia and the Middle East. By most accounts, Australia presently ranks among the top five TNE providers [19] worldwide. The country’s geographic proximity to key TNE markets in Asia alone places the country in a position to further increase [18] its market share of the world’s fast-growing offshore education market.

International Student Mobility

According to Project Atlas [20] data Australia hosts the fourth largest number of international students in the world after the U.S., the U.K., and China. Nearly 24 percent of Australia’s total higher education enrollment is international, the most of any country in the world (and just ahead of the United Kingdom, at 21 percent). Australia’s global market share has also risen over time – from 4 percent of the world total in 2001 to 7 percent in 2017, much at the expense of the United States, also according to Project Atlas.

Overall, Australia is a net importer of students by a large margin with outbound mobility being relatively modest by international comparison. According to UIS [21], the outbound mobility ratio was only 0.8 in 2015, signifying that less than 1 percent of Australia’s tertiary-level students go abroad to enroll in degree programs in other countries.

Inbound Student Mobility

Australia’s preeminence as a destination is often ascribed to the perceived high quality [22] of the higher education system, similar to the reputation of the U.S., the U.K., and Canada. More than 90 percent of foreign students in Australia surveyed in 2016 [23] cited the reputation of Australian education as a reason to study in the country. The fact that English is the national language also plays a role. While the country is anything but a cheap study destination, it is on average less expensive than the U.S. and the U.K. and, by some measures, Canada [24], at least in terms of tuition and fees.

The Australian Government also proactively markets the country as an international study destination. In 2016, the federal government launched Australia’s first formal national strategy designed to make the country an even more competitive destination. The “National Strategy for International Education 2025 [25]” includes objectives, such as ensuring competitive student visa regulations, improving student support services, and strengthening intergovernmental partnerships, particularly in the Indo-Pacific region. At the same time, Australia’s current backlash against immigration and increasingly stringent requirements for those migrating to Australia may jeopardize these objectives. International students already face increasing financial demands, most recently the requirement that they demonstrate personal bank holdings of AUS$ 100,000 [26] (US$ 75,650) for a six-month period in order to obtain a student visa. In late 2017, the government also introduced new stricter English language requirements [27] for international applicants to Australian institutions.

According to the Australian Government’s Department of Education and Training [28], there were a total of 587,942 full-time fee-paying foreign students enrolled at Australian institutions in degree and non-degree programs in 2017 – an increase of 13 percent over 2016. Since a number of these students enroll in multiple programs, the total count of foreign enrollments is higher and stood at 729,790 in 2017 (a 160 percent increase since 2002).

The top five sending countries in 2016 were all in Asia: China, India, South Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam. The top sender, China, had 196,315 total enrollments in Australia in 2016, a nearly 16 percent growth from the year before and comprising almost 28 percent of all international enrollments in the country. India accounted for 78,424 enrollments – an increase of 8.9 percent. The strongest growth in 2016, however, was from Colombia (a 22.4 percent increase), Brazil (19.6 percent), Malaysia (18.2 percent), Nepal (15.9 percent), and Hong Kong (10.3 percent).

Forty-three percent of all international students were enrolled in tertiary education programs, while about 26 and 22 percent of students, respectively, were enrolled in vocational-technical education programs and “English language intensive courses for overseas students,” often known as ELICOS. The states of New South Wales and Victoria, where the major cities of Sydney and Melbourne are located, host the most international students [29] by far.

U.S. and Canadian Students in Australia

For U.S. degree-seeking students at the tertiary level, Australia was the sixth most-favored destination in 2015 (2,942 students), after the U.K., Canada, Grenada1 [30], Germany, and France (UIS [21]). Per IIE’s 2016 [31]Open Doors Report [31], which includes both degree-seeking and non-degree students, Australia was the 8th most popular study abroad destination among U.S. students with 9,536 students during the 2015/16 academic year, up over 8 percent from the year before. Australia has about 3 percent of all U.S. students enrolled abroad.

There is little research into why U.S. students choose Australia or why it is not more popular, aside from small-scale studies and anecdotal explanations. In general, there is relatively little known about U.S. degree-seekers abroad. The typical explanations given, particularly by U.S. media [32], are the relatively cheaper costs of degree programs abroad (and in turn, the high amounts of debt that a U.S. education can cause one to accrue), particularly for graduate school [33]. That may or may not explain the attraction of some U.S. students to Australia, which is known for a high cost of living [34]. The English language certainly also plays a role.

For Canadian degree-seekers, Australia is the third top destination (3,430 students), after the U.S. and the U.K., according to the UIS [21]. Similarly to U.S. students, there are few data and little research on the draw of Canadians to Australia, but the English language, again, is likely a crucial factor. In one 2016 survey [35] of Canadian students, Australia was ranked as the most interesting foreign study destination. This interest, however, does not translate into actual enrollments. In international student statistics [36] provided by the Canadian government, which include both degree and non-degree students, Australia only ranked as the fifth most popular study destination after the U.S. and European countries like France, the U.K. and Germany in 2016.

Outbound Student Mobility

A 2016 survey [37] of 8,663 students2 [38] at Australian universities provides some insights into the study abroad decision-making behavior of Australian students and reflects that the U.S. and other Western countries are the most desired study destinations. Thirty-eight percent of the Australian respondents had already completed a study tour or exchange program during either secondary school or university, and the top destination was the U.S. (15 percent). The U.S. was also cited most often as the most recent destination that respondents had visited and one that they would most like to visit (25 percent among Australians). The top three reasons for studying abroad were “interest in travel” (47 percent of Australian citizens), “learn about another culture” (32 percent), and “strengthen my degree” (32 percent). Among Australians who had not yet participated in a program, the top destination choices were the U.K. (18 percent), the U.S. (18 percent), Canada (9 percent), Germany (6 percent), France (5 percent) and Japan (5 percent). International students in Australia strongly favored the U.S. (22 percent) as a short-term study abroad destination.

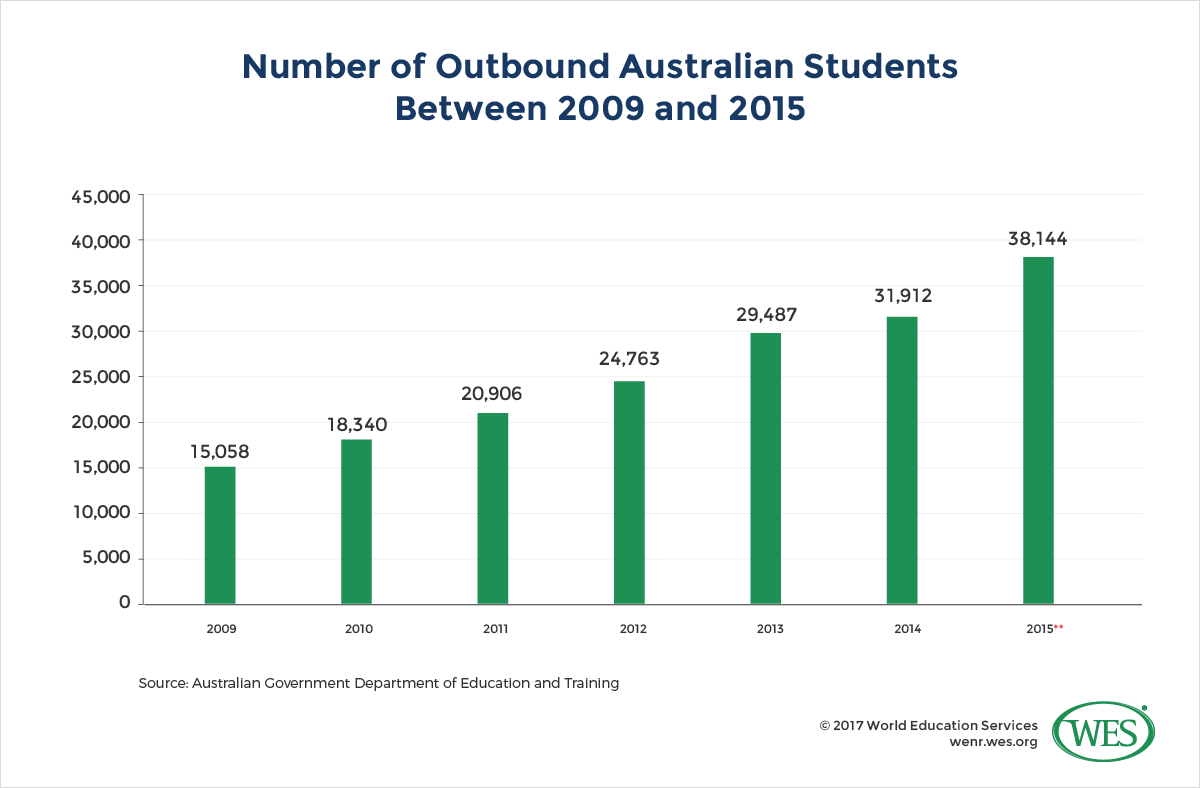

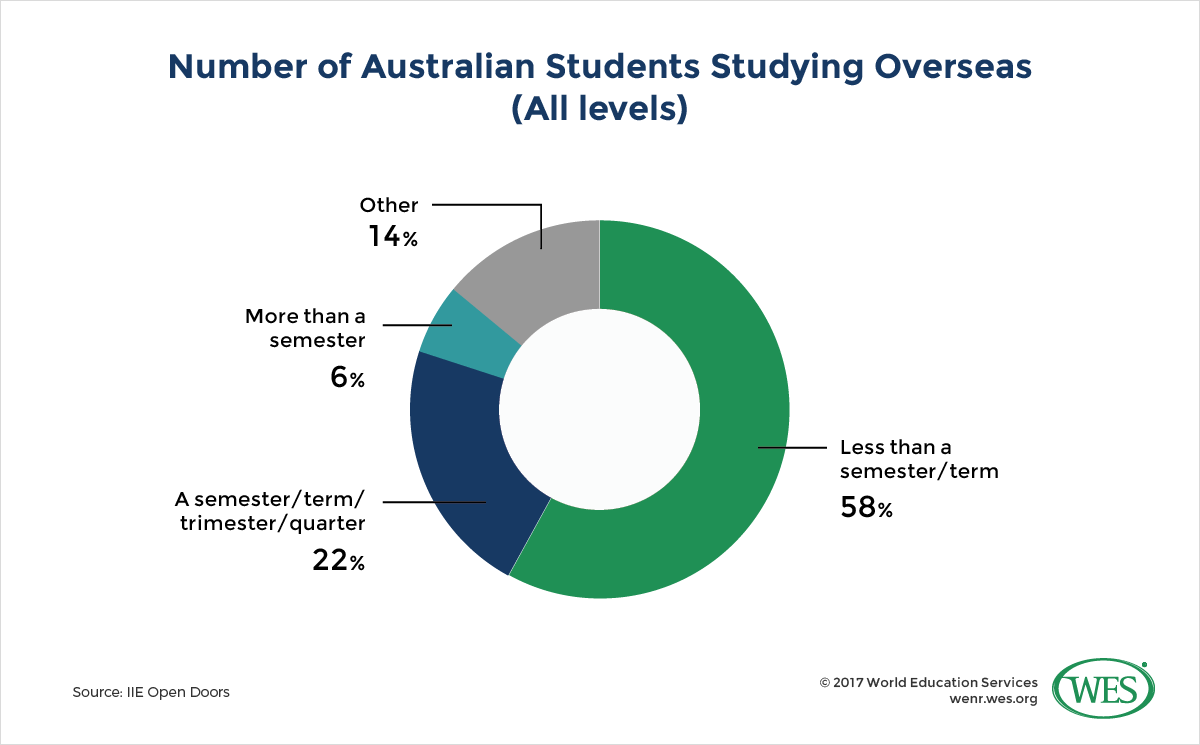

Per UNESCO UIS [21], 12,026 Australian tertiary-level students were enrolled in degree programs in other countries in 2015. The U.S. was the top destination with 3,814 students, followed by New Zealand, the U.K., Germany, and Canada. In addition to these degree-seeking students, 38,144 Australian non-degree students were enrolled in short-term study abroad programs in 2015, according to the Australian Government’s Department of Education & Training [39]. This number represents an increase of 19.5 percent over 2014, which is perhaps unsurprising, given that these short-term exchanges are increasingly for less than one semester and include short-term visits, such as faculty-led study tours.

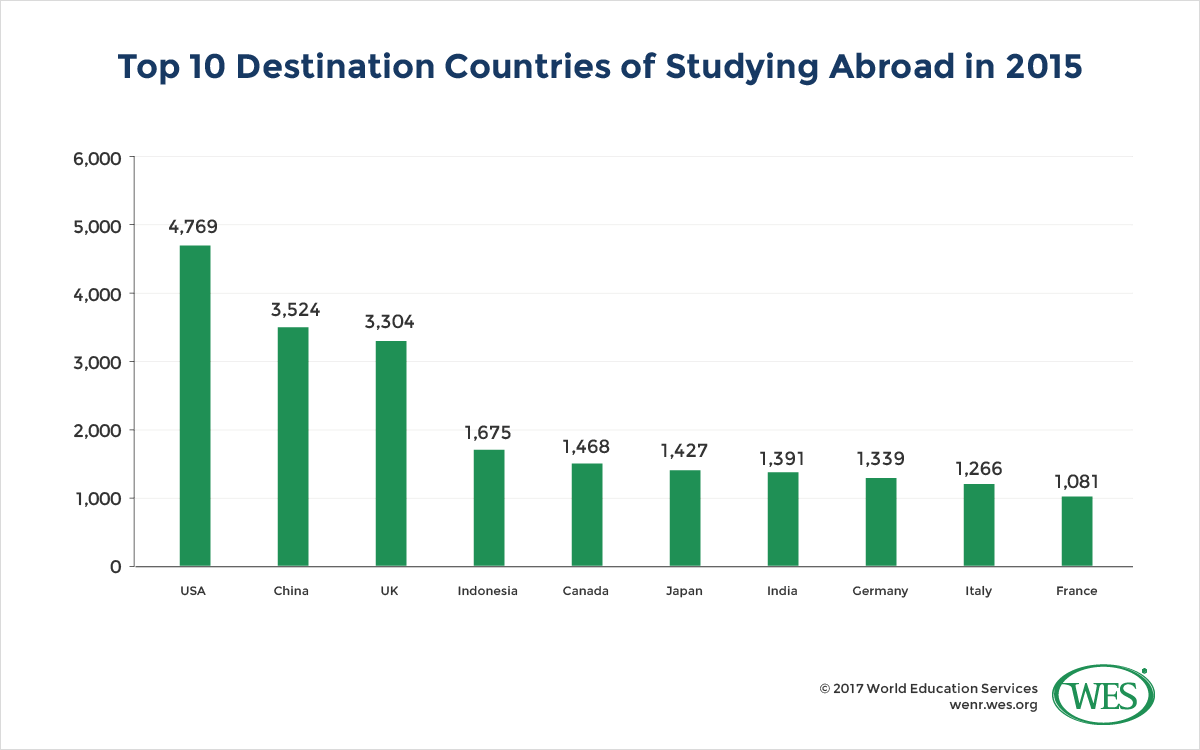

The top destinations [41] among non-degree students were the U.S. (4,769 students, or 13 percent), China (3,524), the U.K. (3,304), Indonesia (1,675), and Canada (1,468). The largest group among these students (20 percent) enrolled in STEM fields, followed by health fields (18 percent), management and commerce (14 percent), and society and culture (14 percent).

The prominence of China and Indonesia as study destinations among short-term students likely owes to the fact that 11,157 Australian undergraduates [41] participated in a program called the “New Colombo Plan [43].” The program is an initiative of Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade designed to promote ties with the Asia-Pacific region through study opportunities and internships for Australian undergraduates. The government provides funding to Australian universities who in turn give grants to students to study or complete internships in one of the target countries. The program will fund 13,000 grants [44] in 35 countries in 2018 but is as of now apparently little known among students. The above-cited 2016 student survey revealed that fully 68 percent [37] of Australian respondents were not aware of the program.

Australian Students in the U.S. and Canada

There were 4,933 Australian students – degree-seekers and short-term exchange students – studying in the U.S. in the 2016/17 academic year, an increase of 3.8 percent from the previous year, according to [46]Open Doors [46]. In 2015/16, 47 percent were undergraduate students, 23 percent were graduate students, 21 were non-degree students, and 9 percent were on optional practical training (OPT) [47]. Overall, the number of students increased by 75 percent over 2005/06, when there were 2, 806 Australians enrolled at U.S. institutions.

Australia is not a major sending country of international students to Canada. According to Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) [48], there were only 710 Australian students enrolled in Canada in 2016, down from 835 in 2014. Australia ranked at the 48th largest sending country. British Columbia hosted the by far largest number of students (425, or around 60 percent), followed by Ontario (330), Alberta (150), and Quebec (115).

Transnational and Distance Education

Australian universities play a substantial and growing role in transnational education (TNE). Ten Australian universities had offshore campuses in 2015 [18], some of the largest of which include Monash University in Malaysia, Wollongong University in Dubai, James Cook University in Singapore, and RMIT (Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology) in Vietnam. In 2015, most of Australia’s offshore students [49] were enrolled in Singapore, China, Malaysia, and Vietnam.

In 2015, a total of 109,541 foreign offshore students [49] enrolled in Australian higher education TNE programs in 2015. Another 39,526 offshore students [49] were enrolled in offshore vocational-technical education programs in 2016. Public Australian universities alone are said to have generated AU$ 382 million from offshore students in 2014 [18].

Rapidly increasing demand for education in many countries means that the future growth potential in the offshore sector is enormous. Based on projected demand in 29 key sending countries of students to Australia, Deloitte Access Economics predicts that if Australian institutions could reach just 1 percent of potential learners, “….this would translate to over 11 million learners in 2025, and if Australia was able to reach 10 percent of these learners that would equate to over 110 million learners [18] in 2025.”

While poor educational quality is a problem sometimes associated with offshore programs, Australian overseas branch campuses are, as of now, run by well-known universities that are fully accredited in Australia. In addition, some of the branch campuses, such as the Wollongong University in Dubai, also have accreditation in the foreign host country [50]. Australia’s Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA [51]) also seeks to ensure quality standards in cross-border programs in collaboration [52] with foreign government bodies and accreditation agencies. It is nevertheless advisable to carefully check the accreditation status of individual TNE programs.

Distance education is another growing sector in both TNE and domestic education in Australia. Fully 23 percent of learners in Australia are said [53] to have studied “either solely or partially through distance education “in 2013. Among international students, more than 10,000 [49] offshore students studied in online or correspondence courses in 2015, while more than 18,000 foreign studies enrolled in distance programs from within Australia.

In addition to distance education programs offered by public universities, there are quite a few private providers in this market. Open Universities of Australia [54] (OUA), which has been in existence for more than 20 years, is a prime example. OUA is a private company owned by a number of universities that offers online programs globally, even though most students are from Australia. While OUA itself is not an award- granting body, it offers a variety of undergraduate and postgraduate programs in cooperation with Australian universities, which develop the curricula and award the final qualification. By some accounts, Australia’s distance education market has grown by more than 14 percent annually between 2009 and 2014 [55] and is expected to expand by another 8.5 percent [56] annually until the end of the decade. Most enrollments, however, are in informal programs rather than tertiary degree programs.

Australia’s Education System

Australia is a highly educated society and ranked 8th among OECD members in terms of tertiary attainment levels [57] in 2015. The country’s literacy proficiency was above OECD average [58] in 2012 and census data shows that the percentage of Australians holding educational attainment at bachelor’s level or higher increased from 17.6 percent in 2006 to 24.3 percent [59] in 2016. Educational attainment among Australia’s indigenous population is significantly lower, while educational attainment is highest among the foreign-born population. The gender gap in education has narrowed, and more women among 20 to 34-year-olds (67 percent) held tertiary attainment than men (62 percent) in 2016.

It should be noted, however, that Australia has simultaneously fallen behind on some education performance indicators in recent years. Australia’s once formidable scores in the OECD PISA study, for example, have dropped steadily [60] over the past 15 years [60]. UNICEF in 2017 ranked Australia third to last [61] among 41 high and middle-income countries in ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education.

Administration of the Education System

The Commonwealth of Australia has a federal system of government in which governance is shared between the federal government in Canberra and six states (New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia). In addition to the federal states, there are ten territories with varying degrees [62] of self-governance. While the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory have a similar degree of autonomy as the federal states, most of the other territories are directly governed by the federal government.

The education system is decentralized – the states and some territories have their own departments of education and set their own education policies. That said, the federal government coordinates education policies, and national education targets are outlined in joint agreements between the states, territories and the federal government. The states and territories share funding for elementary and secondary schools with the federal government. The states and territories contribute about 75 percent [63] of funds, while the rest of funding comes from the federal government, largely for private schools. The public funding of private schools, which include faith-based institutions like Catholic schools and other independent schools, is unusual when compared to other Western countries, and presently a controversial political topic [64]. Most education-related decisions in schooling and vocational education are made by the individual states [65] and territories, even though there is a high degree of intergovernmental coordination.

In higher education, governance is shared between the federal government and the states and territories. Universities are established and recognized under state legislation. Funding, on the other hand, primarily comes from the federal government and subsidizes Australia’s universities, which are largely tuition-funded. Federal government funding for universities is contingent [66] on compliance with quality standards stipulated by authorized accreditation authorities, such as Australia’s Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TESQA). The federal government also funds financial aid and student loans and provides about one-third [66] of funding in the vocational education and training sector (VET).

School Year

The school year in elementary and secondary schools starts in late January or early February, and ends in December [67], while the school year in higher education typically lasts from February to November. Australian seasons are the inverse of those in the Northern Hemisphere.

Elementary Education

Compulsory education in Australia lasts until the end of the age of 16 in most jurisdictions. Schooling is not free – tuition fees are charged even at public schools. School education lasts for 13 years (until age 18) and begins at the – by international standards – early age of five when pupils enter a mandatory “foundation year,” designed to prepare kids for grade 1 of elementary school.

The foundation year is followed by six or seven years of elementary education, depending on the jurisdiction (grade 1 to grade 6 or 7). The curriculum varies by state, but usually includes English, mathematics, social studies, computer technology, science, physical education and health and creative activities. Progression is based on teacher assessments and tests, but there are no standardized year-end or graduation examinations. No formal credential [68] beyond a school transcript is awarded upon completion of elementary school.

While elementary and secondary curricula are set by the governments of the states and territories, a coordinating body, the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [69] (ACARA), was established in 2008 in order to harmonize curricula and ensure the nationally consistent assessment of students. Curricula still vary between jurisdictions, but the core learning outcomes have been standardized. ACARA’s “Australian Curriculum [70]” defines what key competencies pupils should acquire in specific learning areas. A national assessment test (NAPLAN [71]) is conducted each year in grades 3, 5, 7 and 9 to measure how effectively the Australian curriculum has been implemented across the country.

There are nevertheless significant differences between the jurisdictions. Grading scales, for example, are entirely different, depending on the state or territory.

Lower Secondary Education

Lower secondary school begins with grade 7 or 8, and lasts until year 10 (three to four years, depending on the jurisdiction). Admission to public schools is open to students who completed elementary education. However, selective high schools for gifted students in some states require passing of an entrance examination [72]. The core curriculum usually includes English, mathematics, social sciences, science, foreign languages, information and communications technology, arts, and physical education [73]. Additional elective specialization subjects are introduced in higher grades. Promotion is based on internal examinations, written assignments, oral presentations and classroom participation [66]. Standardized external exit exams are not required for graduation in most jurisdictions.

There are no specific credentials awarded upon completion of grade 10 in most states and territories. Students in the Australian Capital Territory, however, receive a “Year 10 Certificate”. New South Wales awarded a “School Certificate” until 2011, but students since just receive a Record of School Achievement (RoSA) [74] – a school transcript listing cumulative academic results.

General Upper Secondary Education

Senior secondary education in Australia is not compulsory, but the official retention rate — the number of secondary students staying in school until the final year of secondary schooling — stood at around 84 percent [75] in 2016 (up from 75 percent in 2006).

Students who have completed year 10 can usually continue on to senior secondary education at their schools – there are no separate entrance examinations. Alternatively, students can opt to enroll in vocational education and training programs (discussed below).

Senior Secondary education comprises grades 11 and 12 in all jurisdictions. As in elementary and lower-secondary education, the state and territory governments determine curricula and assessment standards but integrate [76] ACARA’s Australian curriculum [77]. Fifteen subjects in the key knowledge areas of English, mathematics, science, history, and geography have been endorsed by all states and territories [78] and usually form the core curriculum, in addition to other subjects, such as foreign languages, arts, and physical education. Within these core subject groups, students can usually customize their curricula and choose elective courses.

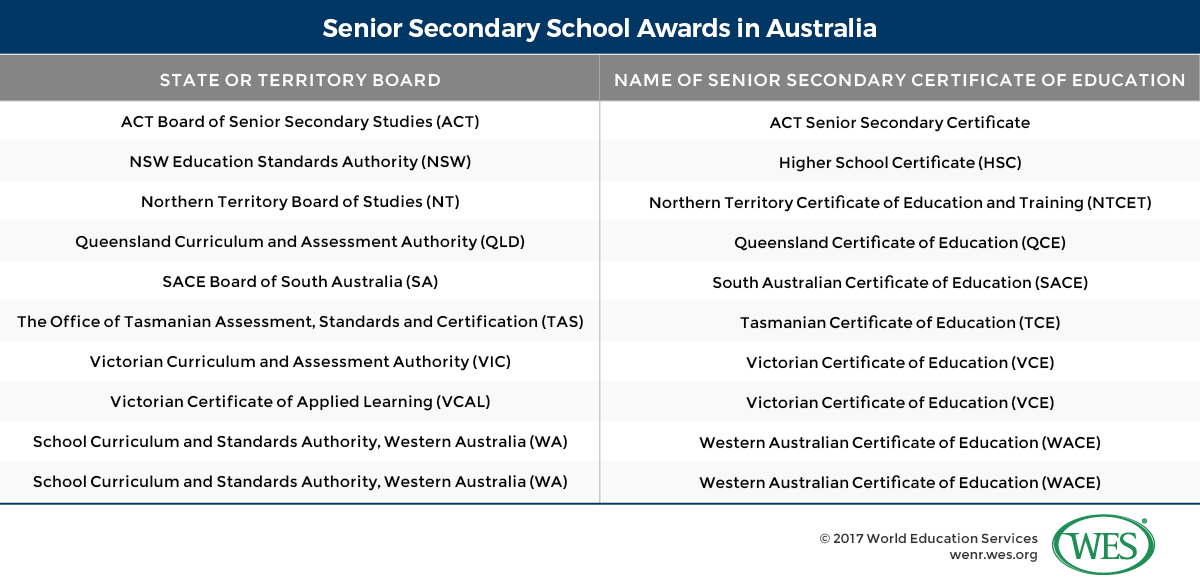

Graduation generally requires completion of certain minimum credit requirements in specific subject groups, and, in most jurisdictions, passing of a final, jurisdiction-wide external examination in grade 12. Content and assessment criteria of the exams vary by jurisdiction. The examination results also play an important role in determining admission to tertiary education. In many states, year 12 scores in designated subjects are used to calculate an “Australian Tertiary Admission Rank” (ATAR), which Australian universities utilize as a selection mechanism. (See also the section on university admissions below) The final credential awarded upon completion of the senior secondary program is commonly referred to as the Senior Secondary Certificate of Education (Year 12 Award), but the exact name differs by state or territory.

Some students in Australia also earn a foreign high school qualification, such as the International Baccalaureate (IB), offered by IB schools in Australia. The IB Diploma is generally recognized as the equivalent of a Senior Secondary Certificate of Education by Australian universities [80]. Growing numbers of foreign students also study for Australian high school qualifications, respectively dual high school awards, in overseas locations. According to the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority, more than 3,000 students [81] have completed the Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE) in China, for instance, since 2002. VCE programs are also offered in the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, the United Arab Emirates, Vanuatu and East Timor. Like domestic schools, overseas institutions that offer Australian curricula must be approved by and registered with one of the state and territory departments of education.

The Cost of Schooling in Australia

A sizeable number of secondary students are in enrolled in private schools – Australia has one of the highest percentages of private school enrollments in the OECD [82]. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, 65.4 percent [75] of Australia’ school students (elementary and secondary) studied at public schools in 2016, whereas enrollments at Catholic schools and independent private schools accounted for 34.6 percent. Schooling in Australia is expensive by international comparison, particularly in metropolitan areas [83]. Costs vary significantly by state, but one 2013 survey [84] found that average tuition fees in metro areas amounted to AU$ 4,455 (US$ 3,383) at public schools, compared to around AU$ 12,599 (US$ 9,567) at Catholic schools and up to AU$ 22,450 (US$ 17,047) at independent private schools.

Vocational Education and Training (VET)

Australia has a large VET sector with a wide variety of programs being offered at the secondary and post-secondary levels. Training is generally employment-geared, has a strong focus on practical training and is primarily provided by so-called “Registered Training Organizations” (RTOs). In 2016, there were 4,279 RTOs, enrolling 4.2 million students [85] (an increase of 4.9 percent over 2015), according to Australia’s National Centre for Vocational Education Research. 26 percent [86] of international students in the country were enrolled in VET programs in 2017.

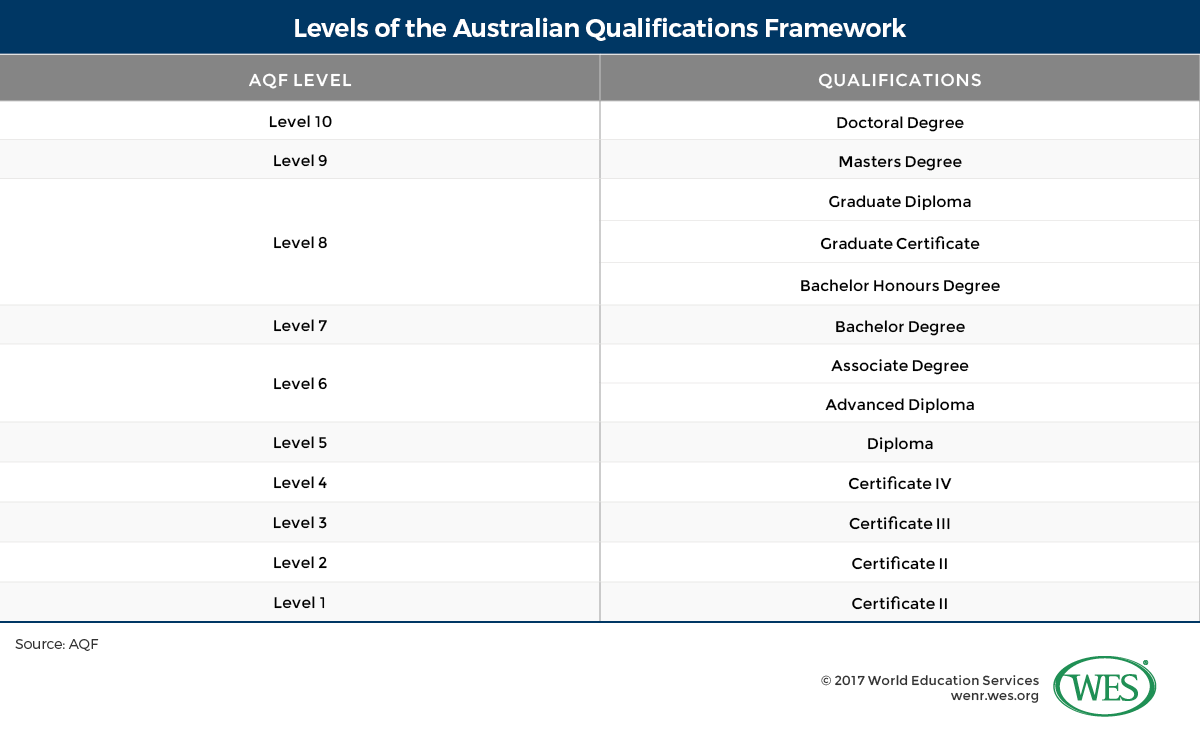

At the secondary level, VET programs lead to the award of certificates of different levels and scope (Certificates I, II, III and IV). Certificate programs provide training in vocational fields and trades at increasing level of complexity. The Certificate IV, at the highest level, is considered equivalent to the Senior Secondary Certificate of Education and gives access to tertiary education (an overview of the different certificates can be found here [66]). The majority of Australia’s VET students pursue certificate programs.

At the post-secondary level, VET programs lead to award of a Diploma, Advanced Diploma, Graduate Certificate or Graduate Diploma. Program lengths range from 6 months in the case of graduate certificates to 1 to 2 years in the case of diploma programs. Graduate certificates and diplomas are also offered in the tertiary sector, but VET programs have a much stronger focus on applied training. Common to all programs is that they convey advanced vocational skills, while simultaneously providing pathways to tertiary education. Holders of VET diplomas and advanced diplomas may be exempted from one or two years of bachelor’s degree programs, respectively, while holders of graduate diplomas may, under certain conditions, be admitted into master’s programs [66].

Admission requirements are flexible, vary by program, and are much less formalized and sequential than in tertiary education. Generally, the minimum requirement for certificate programs is completion of grade 10 or a certificate at preceding levels, whereas the benchmark for post-secondary programs is usually a Year 12 or a Certificate IV at minimum, even though admission may also be based on work experience or other criteria.

In addition to school programs, VET can be undertaken in apprenticeship programs at a workplace. Programs are open to anyone [87] of working age and offer students the opportunity to earn a vocational qualification while working. The concrete delivery method differs by program, but programs commonly combine practical training at work with theoretical instruction at an RTO. Programs are designed [88] by the state and territory governments in consultation with industry and lead to officially recognized qualifications. There are more than 1,000 program options in a variety of fields ranging from agriculture to automotive technology, financial services, construction, allied health, hairdressing, telecommunications or retail [66].

Assessment in VET programs is usually based on the achievement of certain core competencies tested in examinations, projects and practical tests. The learning outcomes of RTO programs are defined in so-called “training packages,” which are designed in consultation with industry and approved by the federal and state and territory governments for consistent use in all of Australia [89]. These “packages” define admission requirements, curricula, required competency units, assessment criteria and the placement of programs within Australia’s National Qualifications Framework (see below).

The different training packages are cataloged in a “National Register of Vocational Education and Training [90],” maintained by the federal Department of Education and Training. The National Register also lists all RTOs that are approved to offer accredited courses.

There is no grading scale for VET courses; instead, all units taken are marked as pass/fail, or competent/not competent. As such, the academic transcripts for VET qualifications only list units of competency that have been completed successfully.

VET Providers and Oversight

Registered Training Organizations can be divided into two categories: private RTOs and public institutes of “Technical and Further Education” (TAFE [91]), administered by the governments of Australia’s states and territories. TAFEs are the largest VET providers and are sometimes affiliated with universities. RTOs may also be Higher Education Providers (HEPs) and offer accredited tertiary education programs, such as a bachelor’s degree programs.

Oversight over VTE and RTOs involves a number of different agencies and government bodies, depending on the jurisdiction. However, the most important regulatory authority is the national “Australian Skills Quality Authority” (ASQA [92]). ASQA was established in 2011 in a “National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Act [93],” designed to ensure nationally consistent high-quality VET. In most jurisdictions, RTOs must be registered with ASQA in order to offer accredited programs. To qualify for registration, RTOs must be responsive to industry and learner needs, offer programs in compliance with official training packages, have adequate quality assurance mechanisms and be financially viable. (For more information, see the federal “Standards for Registered Training Organizations [94],” 2015)

There is a separate accreditation process [95] for individual training programs. However, course accreditation is not compulsory, and RTOs can deliver non-accredited programs, partial training packages or “non-award courses.” Delivery of partial packages and non-awards courses nevertheless requires fulfillment of quality standards stipulated by ASQA.

To distinguish accredited qualifications from non-recognized qualifications and to protect against the fraudulent issuance of documents, ASQA uses the trademark logo “National Recognized Training [96]” (NRT). Permission to use the NRT logo is only granted to duly authorized institutions and can only be displayed on academic documents if the program is accredited and leads to an official Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) qualification. The Australian Qualifications Framework Council established a similar “AQF Qualifications Issuance Policy [97]” and uses a trademark logo that can only be displayed on formal AQF qualifications. If the NRT and AQF logos are displayed on academic documents in the proper format, it can, therefore, be assumed that the program in question is accredited.

Of note for credential evaluators is also the fact that ASQA maintains the records of attainment for RTOs that went out of business or were shut down. It may, therefore, be possible to obtain official documentation from ASQA even if RTOs are no longer operating.3 [98]

The Australian Qualifications Framework

The Australian Qualifications Framework [99] (AQF) was established in 1995 and defines levels, learning outcomes, and length of programs of regulated qualifications in Australia, as agreed to by the federal, state and territory governments. The framework ensures that qualifications are recognized across Australia and specifies which institutions are authorized to award the different qualifications. The AQF encompasses VET and tertiary education. There are ten levels ranging from the Certificate I to Doctoral degree. The Senior Secondary School is also included in the framework but not pegged at a specific level.

Tertiary Education

University Admissions

The university admissions process in Australia is complex and varies by jurisdiction. Universities generally have autonomy to set their own admissions criteria, but all states and territories have centralized admissions authorities [66], referred to as Tertiary Admissions Centers (TACs), as well as state-specific systems for the ranking of students. Universities admit students based on a quota system with higher-ranked students having better chances of admission.

Eligibility criteria and minimum scores for admission differ by institution and program. While criteria like the grade point average in senior secondary school, portfolios or interviews may factor into admissions decisions, admission is commonly based on the Australian Tertiary Admissions Rank (ATAR). The ATAR is a number between 0.00 and 99.95 that ranks students in relations to other students. A score of 80.00, for instance, means that a student is in the top 20 percentile and ranked better than 80 percent of the population eligible to be in year 12 at the time of graduation [101]. The calculation criteria differ by state [102] but are usually based on year 12 grades and examination results in specific subjects.

The state of Queensland uses a different system called “Overall Positions [103]” (OPs) that ranks students on a scale from 1 to 25, with 1 being the highest position. OP ranks are calculated according to a complex scaling method [104] that ranks students in relation to other students both within their school, as well as in relation to other schools in the state.

Alternative pathways to tertiary education include admission based on VET qualifications (discussed below) or the completion of preparatory bridging courses. Mature students over the age of 25 may be admitted based on relevant work experience, entrance examinations, and interviews.

Overall, the admissions rate in Australia is relatively high in comparison to other OECD countries. Out of 340,027 students who applied for undergraduate admissions either though TACs or directly to universities in February 2017, 82.7 percent [105] received admission offers.

English Language Intensive Courses for Overseas Students (ELICOS)

International applicants to Australian universities usually have to demonstrate adequate English language proficiency [106] and submit results from standardized English language tests, such as the TOEFL or IELTS. An alternative option for foreign students without adequate English prerequisites is to enroll in intensive English programs in Australia before assuming further studies. Enrollment in this sector is booming: 127,227 international students were enrolled in ELICOS programs in September 2017, making up 17 percent [86] of all international students in Australia.

While English language requirements vary by institution, it is presently possible for graduates of ELICOS programs to transition into tertiary programs without further external examination at a number of universities. In October 2017, however, the Australian government tightened ELICOS standards [107] and announced [108] that it would introduce an English-language test for ELICOS students in Australia.4 [109] The tighter restrictions, which also stipulate a minimum of 20 hours of instruction a week, came amidst concerns that not all ELICOS programs adequately prepare students to take up studies in English. Providers in the VET sector, which were previously exempted from ELICOS standards, will now also have to comply [110] with the regulations.

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs)

Australia’s higher education sytem includes 43 universities and 122 [111] recognized non-university higher education providers (HEPs), such as colleges and institutes. Universities are multidisciplinary institutions that are “self-accrediting,” that is, they are authorized to have internal quality assurance mechanisms for their programs and do not need to apply for external program accreditation. They are predominantly public – there are only three private Australian universities (Bond University, the University of Notre Dame Australia and Torrens University Australia). In addition, there are two foreign-owned private universities (Carnegie Mellon University Australia and the University College London Australia) One university, the University of Divinity is classified as an “Australian University of Specialization.” It offers specialized programs in theology, religious philosophy, and ministry.

Eight of the largest and most prestigious public Australian research universities have formed the so-called Group of Eight (Go8) [112]. All Go8 Universities receive extensive research funding and are ranked high in international university rankings. The University of Melbourne, for instance, ranked 33th in the 2017 Times Higher Education Ranking [113] and the Australian National University ranked 20th in the 2018 QS ranking [114]. Other Go8 universities among the top 100 in both rankings are the University of New South Wales, the University of Queensland, the University of Sydney and Monash University.

The non-university HEIs in Australia are a heterogeneous group that is different to categorize, but mostly includes smaller mono-specialized providers, many of them private. To name but one example, the private for-profit Kaplan Higher Education Corporation operates “Kaplan Professional [115]” – a registered HEP authorized to award a range of qualifications from diplomas to master’s degrees in business majors. Most of these institutions are not authorized to operate as self-accrediting institutions, even though there is a small number of self-accrediting non-university institutions as well.

Accreditation and Quality Assurance

All higher education institutions need to be approved and licensed by the state and territory governments. In addition, HEIs are subject to quality control by the National Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency [51] (TEQSA), established in 2011 as the national regulatory and quality assurance agency for higher education. TESQA evaluates institutions and programs against detailed benchmark criteria laid out in the “Higher Education Standards Framework (Threshold Standards) 2015 [116]”, which include adequate admissions procedures, program structures, assessment criteria, teaching staff, facilities, governance and quality assurance mechanisms.

HEIs without self-accrediting authority must seek program accreditation by TESQA for all programs leading to AQF qualifications and must offer at least one TESQA-accredited program to qualify for registration as a HEP. Accreditation and registration are valid for seven years, after which institutions need to apply for re-registration and re-accreditation of programs. HEIs with self-accrediting authority are obligated to internally re-evaluate and accredit their programs every seven years [66].

Tertiary Education Spending

Higher education institutions in Australia are to a large extent funded by tuition fees and other private sources: 48 percent of expenditures in tertiary education in 2014 came from private sources compared to an average of 22 percent [117] in the OECD. Higher education in Australia is not cheap – domestic students, including Australian citizens, Australian permanent residents, and New Zealand citizens, currently pay between AU$ 15,000 (US$ 13,663) and AU$ 30,000 (US$ 22,770) [118] in annual tuition fees for bachelor’s programs. The costs for postgraduate programs are even higher, and international students tend to pay more for education than domestic students.

Government expenditures for education are nevertheless relatively high in Australia compared to other industrialized countries [119]. Education spending amounted to 5.23 percent [120] of GDP and 14 percent [121] of total government expenditures in 2014, according to the World Bank. 26.5 percent [122] of these expenditures were allocated to the tertiary sector (an increase from 22.3 percent in 2010) and averaged US$ 18,038 per student [123] in 2014, compared to an average of US$ 16,143 in the OECD.

A sizeable portion of federal government spending is allocated to financial aid to help Australian students offset the high costs of education (tuition subsidies, student loans and scholarships). More than half of Australian undergraduate students currently receive some form of financial support – a burden on the government, especially since student numbers have been growing strongly in recent years (see below). To reduce expenditures, Canberra in May 2017 introduced a higher education reform package [124] that would entail drastic spending cuts [125] and increases in tuition fees for undergraduate students. However, the government has so far failed to get the reforms approved by Australia’s parliament [126].

Student Enrollments

In 2016, there were close to 1.46 million students [127] enrolled in higher education programs in Australia, an increase of 3.3 percent from 2015. More than 90 percent of these students were enrolled at public universities. Enrollments at private universities and non-university HEPs, however, are on the rise and increased by 10.2 percent since 2015 to 132,703 students [127] in 2016. According to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics [17] (UIS), the share of private sector enrollments among all tertiary enrollments grew from 0.3 percent in 1999 to 8.5 percent in 2014. One probable reason for this expansion is that the educational niche offerings of private providers are increasingly attractive to Australian learners. Compared to public universities, private institutions also admit more students based on alternative entry pathways (mature age and other special entry provisions), so that private education in Australia tends to increase access and educational opportunities [128].

The total number of students in Australia in both public and private institutions increased by more than 70 percent between 1999 and 2016 (there were 845,636 tertiary students in 1999, according to the UIS). A sizeable amount of this increase can be attributed to the mounting influx of international students over the past two decades. But enrollments by domestic students also expanded rapidly: domestic undergraduate enrollments, for instance, increased by 21.3 percent [128] between 2001 and 2012 alone. Postgraduate enrollments are also growing: the share of enrollments in postgraduate programs among all enrollments increased by 30 percent [129] between 1984 and 2014. This rise in student enrollments is primarily driven by population growth and vastly expanded participation rates in higher education. Australia’s entry rate in bachelor’s degree programs and other equivalent tertiary education programs, for instance, increased by 32 percent [130] between 2005 and 2015, according to the OECD.

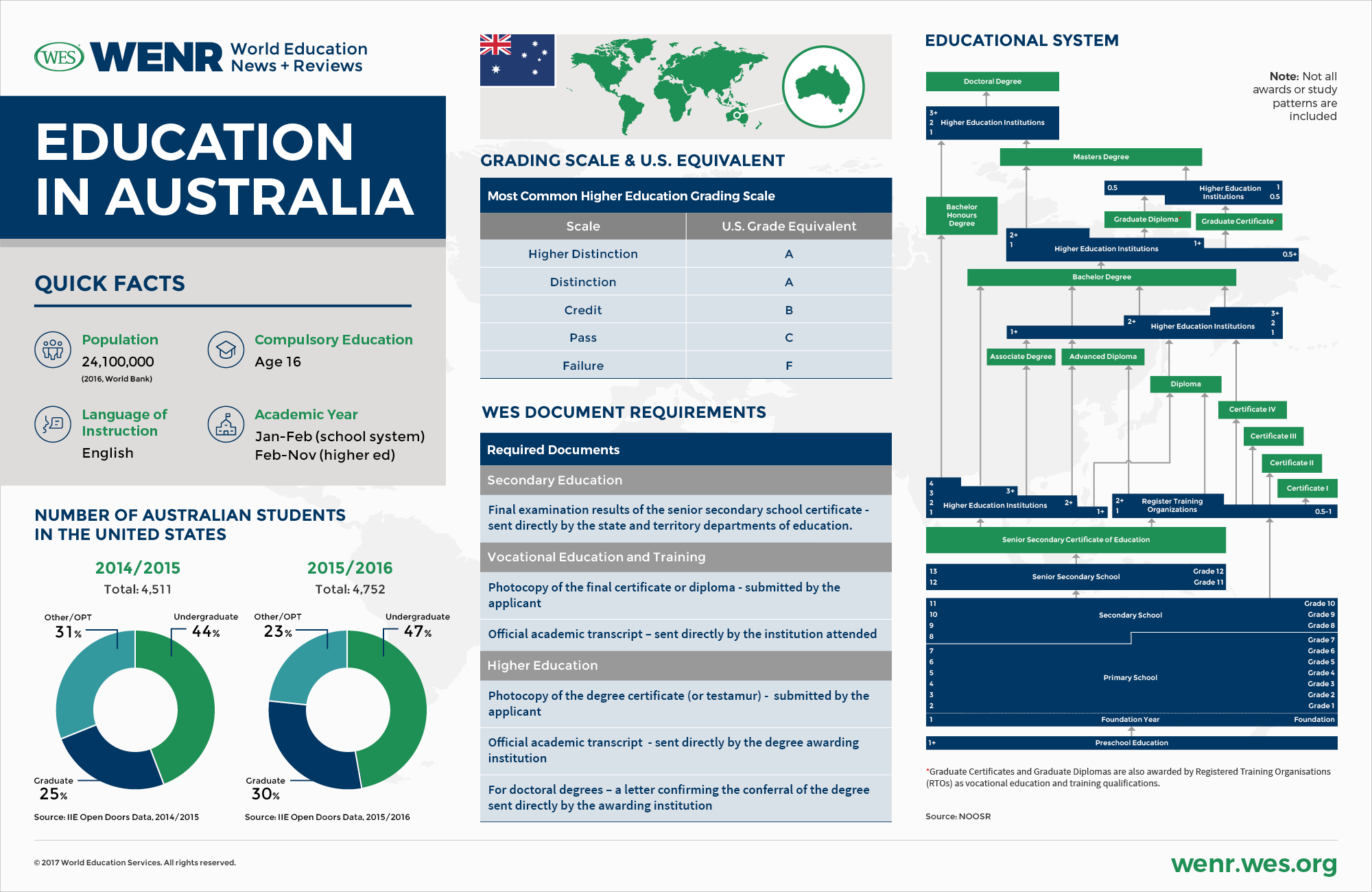

Credit Systems and Grading Scales

There is no standard credit system in use throughout Australia – credit systems vary widely by institution. Most commonly, the standard number of courses required for one year of full-time study in undergraduate programs is eight courses (or units), but the exact credit value assigned to these courses varies. At Monash University, for instance, the standard credit load for one year of full-time study is 48 credit points [131], whereas one year of study at the University of Melbourne is 100 credit points [132] per year. To make credit units comparable and allow for the transferability of courses between institutions, universities in Australia therefore also convert their credit units into a standard measurement unit called “Equivalent Full-Time Student Load (EFTSL).” One EFTSL unit represents one year of full-time study. To give an example, the standard undergraduate credit load at Griffith University is 8 courses or 80 credits per year. Griffith converts each standard 10 credit course into 0.125 EFTSL [133] (8 x 0.125 = 1 EFTSL).

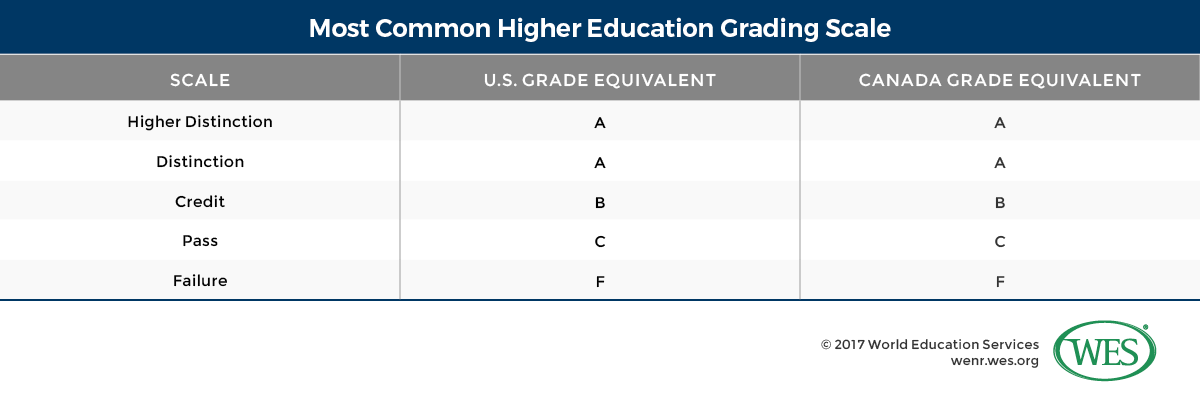

Grading scales used in Australia also differ significantly by institution. There are a multitude of scales, ranging from A to E letter grade scales (with A as the highest grade) to 1 to 7 numerical scales (with 7 as the highest grade) and 0-100 scales. The most widely used scale, however, uses descriptive grades from “High Distinction” to “Failure.”

Degree Structure

Associate Degree, Associate Diploma, and Advanced Diploma

Short first degree programs in Australia are pegged at level 6 of the Australian Qualifications Framework. Associate degree and associate diploma programs are typically offered at universities, non-university HEPs (colleges, institutes) and sometimes RTOs. They are commonly two years in length, even though they may be shorter. The standard admission requirement is the Senior Secondary Certificate of Education or an equivalent qualification like the Certificate IV. Advanced diplomas programs are more applied in focus and offered by RTOs, universities and other HEPs. Graduates of level 6 qualifications may be exempted from the first two years of study in bachelor’s programs.

Bachelor and Bachelor Honours Degree

Bachelor’s programs are primarily offered at universities and are typically three years in length in standard academic fields like arts, commerce or science. The standard admission requirement is the Senior Secondary Certificate of Education or an equivalent qualification. Curricula are specialized – there is usually no general education component.

Bachelor Honours degrees are at a higher academic level than ordinary bachelor’s degrees. Honours degrees are pegged at level 8 of the AQF, whereas ordinary degrees are pegged at level 7. Honours programs typically build upon an ordinary bachelor’s degree and require one additional year of study. Alternatively, honours programs are also offered as 4-year integrated programs that incorporate the ordinary degree curriculum. The honours component involves writing of a thesis and completion of academic subjects at advanced level in the area of specialization. Relatively few students complete the honours program. Holders of honours degrees with high grades may be admitted into doctoral programs without completing a master’s degree, an option that is not available to holders of ordinary degrees.

Dual Degree Programs

Australian institutions offer a variety of dual degree programs – a flexible fast-track option to earn two degrees in different fields of study. These programs may also be referred to as joint or conjoint degrees, double degrees, combined degrees or vertical double degrees. What is common to these programs that they are structured study programs that allow students to earn two degrees in a shorter time (typically four or five years for dual bachelor’s programs) than it would take to complete two separate programs. The total credit requirements for dual degree programs are lower compared to the credits units required for two separate programs. As an example, Canberra University offers a dual degree program leading to a “Bachelor of Commerce/Bachelor of Event and Tourism Management” that requires 96 credit points [135] (four years of full-time study). Dual degree programs also exist at the master’s level and are becoming increasingly common in professional disciplines. Students, in this case, can simultaneously earn a professional degree together with a degree in a standard academic discipline. The University of Melbourne, for example, offers a dual “Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery and Bachelor of Arts” program [136].

Graduate Certificate, Graduate Diploma, and Postgraduate Diploma

Graduate Certificates and Graduate Diplomas are pegged at level 8 of the AQF, and deliver specialized education beyond a bachelors’ degree, which is typically required for admission (although alternative entry pathways do exist). Graduate certificates usually require one semester of full-time study, whereas graduate diplomas typically require one year of study. Graduate certificates and graduate diplomas are awarded by universities and other HEPs, as well as by RTOs, in which case programs tend to have a focus on vocational skilling.

Another short-term graduate qualification awarded by Australian institutions is the Postgraduate Diploma. Some universities use the terms “Graduate Diploma” and “Postgraduate Diploma” interchangeably, but other universities differentiate between them. Curtin University, for example, stipulates that admission into graduate diploma programs is “normally based on a bachelor degree or diploma. Exceptions may be made in the case of less academically qualified applicants with appropriate work experience [137].” Admission into postgraduate diploma programs, on the other hand, is reserved for students “who have completed a bachelor degree in a particular discipline, and want to further their studies in the same area [137].”

Both graduate diplomas and postgraduate diplomas may be issued as exit qualifications in incomplete master’s programs. Some universities also award postgraduate diplomas as a regular component of master’s programs and issue the diploma after completion of the first year of study. Students who complete the master’s program will be awarded both the master’s degree and the postgraduate diploma.

Masters Degrees

Master’s degrees are pegged at level 9 of the AQF. The length of the programs is somewhat flexible and depends on the prior education of students. Students who have completed a level 8 honours bachelor’s degree, graduate diploma or postgraduate diploma can usually complete a master’s program in a shorter amount of time than students entering with a level 7 ordinary bachelor’s degree. The length of the program also depends on whether the bachelor’s degree was completed in the same academic discipline as the master’s program. Programs tend to be longer if the bachelor’s degree was earned in a different field.

Australian universities award three different types of master’s degrees:

- Masters Degree (Coursework). Programs are one to two years in length, depending on the prior education of the student. Study normally involves a set amount of specialized coursework and completion of a final project, but a research thesis is not required.

- Masters Degree (Research). Programs are more research-oriented and normally take one to two years, depending on the prior education of the student. Completion of a research thesis is typically required for graduation in addition to coursework. An honours bachelor’s degree or level 8 graduate diploma may be required for admission in some cases.

- Masters Degree (Extended). These types of programs are relatively new and designed to provide advanced academic training in professional disciplines, such as medicine, health fields or pharmacy, for example. Programs usually last three to four years and require coursework and a final project. The minimum admission requirement is typically a level 7 bachelor’s degree.

Doctoral Degree

The Doctoral degree is the highest qualification in the AQF, pegged at level 10. Programs take 3 to 4 years to complete and require a master’s degree or an honours bachelor’s degree earned with high grades for admission. There are two types of doctoral degrees:

- Doctoral Degree (Research): Programs require completion and defense of an original research thesis and lead to the award of a Doctor of Philosophy. Most programs are purely research-based, but a limited amount of coursework may also be required in some cases.

- Doctoral Degree (Professional): Professional doctorates are designed to advance knowledge and practices in professional disciplines. Programs consist of both advanced coursework and applied research. Credentials awarded include the Doctor of Education and Doctor of Technology.

In addition, there is a Higher Doctorate, which is an honorary degree similar to the honorary doctorate in the United States. It is awarded to individuals who have made internationally-recognized contributions to their fields of knowledge. No formal study or assessment is required.

Professional Education

Professional entry-to-practice degree programs in disciplines like medicine, dentistry, law, or engineering are either long single-tier programs entered directly after secondary school or postgraduate programs following a bachelor’s degree in a standard academic discipline. In the first case, programs are between four and six years in length, while programs in the latter case last between three and four years.

Credentials awarded include the Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS), Doctor of Medicine, Bachelor of Dental Surgery, Doctor of Dental Surgery or the Bachelor of Laws. Professional bachelor’s degrees may have an honours designation, but the designation, in this case, is simply used to denote outstanding performance and does not signify additional study.

Admission into medical programs is quite competitive. Entry into Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) programs after high school may require interviews and mandatory secondary course pre-requisites, such as high-level mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology and English. In addition, students must also pass the “Undergraduate Medical and Health Sciences Admission Test” (UMAT [138]). UMAT is held in July each year and the results are only valid for one year. MBBS programs are usually six years in length and combine theoretical instruction with clinical practice.

Medical programs are also offered on a postgraduate track of four-year duration. The two credentials awarded on this track are the MBBS and, increasingly, the Doctor of Medicine, both of which have equal professional standing. Admission into these programs requires an undergraduate degree, interview, and passing of the “Graduate Australian Medical Schools Admission Test” (GAMSAT [139]). GMSAT is offered twice a year in March and September, and the results are valid for two years.

After graduation, students are required to complete a clinical internship of at least one-year duration in order to register as general medical practitioners. Registration in medical specialties requires a further three to six years [140] of residency training, depending on the specialty.

Dental education is structured similar to medical education. The Bachelor of Dental Surgery (B.D.S.) (also awarded as Bachelor of Dentistry or Bachelor of Dental Science) is a five-year program that requires certain secondary course-prerequisites and passing of the UMAT for admission. Postgraduate credentials include the B.D.S. and the Doctor of Dental Medicine (DMD). Postgraduate programs last three or four years and require an undergraduate degree, interview, and passing of the GAMSAT for admission. Curricula in all programs combine theoretical instruction with clinical practice. Dental graduates must register with the Dental Board of Australia [141] in order to practice as a dentist. The registration needs to be renewed every year. Registration as a dental specialist requires in dental specialties requires additional training [142].

Teacher Education

The minimum requirement to work as a teacher in Australia is a bachelor’s degree at all levels of schooling. Teacher education programs in Australia are offered at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. Undergraduate Bachelor of Education programs are usually four years in length, whereas graduate-entry “top-up” Bachelor of Education programs involve two years of study following a bachelor’s degree in another field. Alternatively, prospective teachers can earn a two-year Master of Teaching degree (for an overview of programs see the list of accredited programs [143] published by the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership – AITSL). Curricula include a practice teaching component. Prior to graduation, all students enrolled in an initial teacher education program must pass a mandatory “Literacy and Numeracy Test for Initial Teacher Education Students” (LNTITE [144]). All graduates must register with the regulatory authorities for teacher education in one of the states or territories [145].

Documentation Requirements

Secondary Education

- Final examination results of the senior secondary school certificate – sent directly by the state and territory departments of education.

VET

- Photocopy of the final certificate or diploma – submitted by the applicant

- Official academic transcript – sent directly by the institution attended

- For study completed at an RTO that no longer operates – academic transcript forwarded electronically by ASQA

Higher Education

- Photocopy of the degree certificate (or testamur) submitted by the applicant

- Official academic transcript sent directly by the awarding institution

- For doctoral degrees – a letter confirming the conferral of the degree set directly by the awarding institution

Sample Documents

Click here [146] for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Victorian Certificate of Education

- Higher School Certificate, New South Wales

- Certificate IV

- Associate Degree

- Bachelor of Behavioral Science (3 years)

- Bachelor of Education

- Honours Bachelor Degree (3+1 mode)

- Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery

- Graduate Diploma

- Masters Degree

- Doctor of Philosophy

1. [147] Grenada and other Caribbean island nations are known to host [148] significant numbers of U.S. (and Canadian [149]) medical students enrolled at offshore medical schools.

2. [150] The survey commissioned by “Universities Australia” included Australian citizens, permanent residents and even some international students in Australia (18 percent of the sample).

3. [151] It should be noted that the “trading name” of a RTO can be different from its legal name. A trading name is the name the RTO uses when issuing the academic documents, whereas the legal name is the registered business name. Both the trading name and the legal name of an RTO are listed in the National Register of Vocational Education and Training.

4. [152] Despite the government’s announcement, there is presently confusion about the exact testing requirements with some ElICOS providers maintaining that there are no new compulsory tests under the current regulations. See: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-10-20/new-english-standards-for-international-students-cause-confusion/9066546 [108]