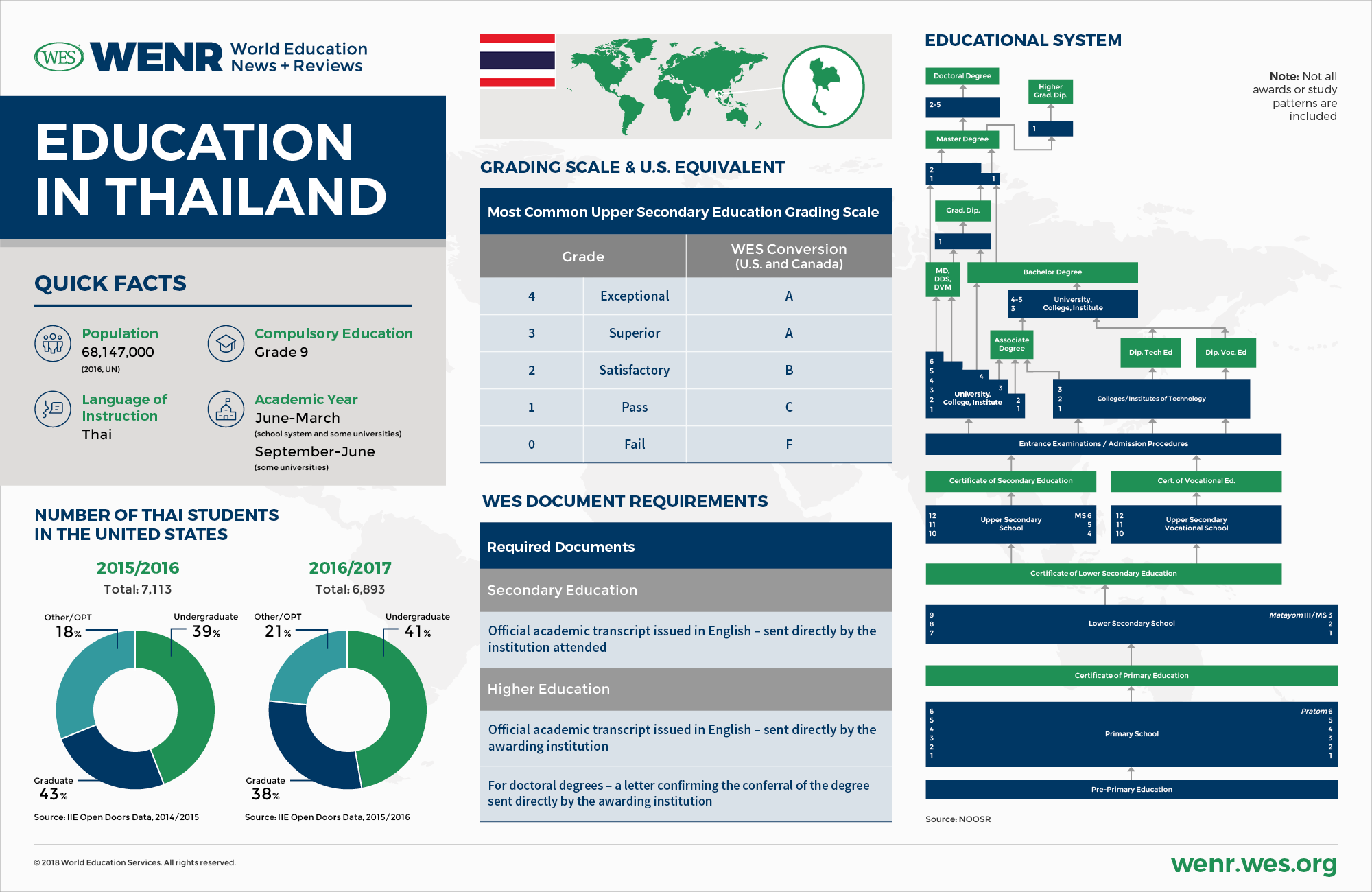

Rachel Michael, Policy Management Specialist at WES, and Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Thailand’s economy and education system are currently affected by political instability and a rapidly aging populace. This education profile describes recent trends in Thai education and student mobility, and provides an overview of the structure of the education system of Thailand. This article replaces an older version by Nick Clark.

In tourism brochures, Thailand is often marketed as a “land of smiles” – a welcoming tourism paradise known for its tropical beaches, hospitality, historical sites and world-famous cuisine. Over the past decades, the Southeast Asian country of 68,147 million (2016, UN [3]), has become one of the world’s top tourism destinations, hosting 32.6 million international visitors [4] in 2016. In that year, direct and indirect tourism revenues contributed more than 20 percent [5] to the Thai GDP – a far above average percentage by international comparison.

Political Instability

Its image as a topical paradise notwithstanding, Thailand faces a number of formidable challenges. The growing influx of international visitors into Thailand comes despite the fact that the country continues to be marred by political instability, intermittent military dictatorship, human rights abuses and civil war. Thailand is not only a “land of smiles”, but also a “land of military coups”: it is amongst the world’s countries with the most military coups [6] in recent history. Since 1932, there have been almost as many coup attempts in Thailand as there have been democratic elections: there were no less than 19 military coup attempts, [7] 12 of them successful. In the most recent past, the military intervened into the country’s politics in 1981, 1985, 1991, 2006 and 2014.

The frequent military coups in recent years are a reflection of the deep social conflicts between the country’s traditional political establishment – urban upper classes, royal and military elites – on one hand, and the rural population majority in the Thailand’s north and lower urban classes on the other hand. Royal elites have always had a strong influence on Thai politics, and the country remains a constitutional monarchy until today. Social change and increasing political participation of more social groups in the north, however, have over the past decades ushered in governments that weakened the traditional elites’ grip on power. Backed by the formerly marginalized electorate in the north, the political dynasty of media mogul Thaksin Shinawatra, and later his sister Yingluck Shinawatra, succeeded in establishing a highly efficient political machine that won every parliamentary election since 2001. Both Thaksin and Yingluck were loathed by the traditional elites, accused of corruption, and removed from the position of prime minister by military or judiciary coups. Both are banned from running for office in Thailand and have fled the country to avoid imprisonment.

The latest military coup in May of 2014 ended hopes that Thailand could become a stable democracy in the near term and demonstrated that Thailand’s traditional elites are unwilling to cede power. The Thai armed forces overthrew the democratically elected government and established a military junta under General Prayuth Chan-ocha, which continues to run the country four years later, despite promises of new democratic elections. Elections are now said to take place in November 2018 under a new constitution that all but guarantees the military’s grip on power and, as observers have noted [8], allows “the military and their royalist backers to oversee Thai politics for the foreseeable future, whatever the outcome of elections”. Human Rights Watch observed in 2017 that the military government continued its “crackdown on basic rights and freedoms, and devised a quasi-democratic system that the military can manipulate and control (….) Three years after the coup, the junta still prosecutes peaceful critics of the government, bans political activity, censors the media, and stifles free speech [9]”. It is not guaranteed [10] that elections will indeed take place in 2018.

Unsurprisingly, the climate of political repression curtails academic freedom and causes Thai academics to work under the constant threat of surveillance, political reprisal and arrest. The expansive use of Thailand’s lèse-majesté laws and other draconian legislation, for example, has resulted in the jailing of student activists [11] critical of the monarchy or Thailand’s new pro-military constitution. In the summer of 2017, the military government arrested five academics attending an academic conference in Chiang Mai on charges that the conference violated the junta’s ban on political gatherings of more than five people [12].

Civil War

Another fault line in Thai politics is the conflict between the Buddhist Thai majority and the Muslim Malay minority in the country’s culturally distinct “deep south” at the border with Malaysia, which has spawned an armed insurgency of militant Malay separatists. The little-publicized civil war is currently in its 14th year and has cost close to 7,000 lives [13]. After the government of Yingluck Shinawatra tried to intensify peace negotiations, the military junta has adopted a more intransigent stance. The war currently shows no signs of dying down and resulted in 307 casualties in 2016. [13]

Slow Economic Growth

Economically, the political instability in Thailand has done little to assure foreign investors. Economic growth rates decreased from 7.2 of GDP in 2012 [14] to 0.9 percent in 2014. The economy has since stabilized, but some observers nevertheless fear that Thailand’s middle income economy is on course for a “lost economic decade [15]”, squandering opportunities for much stronger economic growth. Thailand continues to be plagued by a high degree of corruption [16] and economic growth remains below average in the ASEAN community. Thailand’s economy is projected to grow by 3.1 percent in 2018, whereas the economies of Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Cambodia, are expected to grow by 4.2 percent, 4.9 percent, and 5.7 percent, respectively [14].

Demographic Decline Fuels Crisis of Education System

Another problem with a more immediate impact on the education system is Thailand’s brisk demographic decline. Thailand’s population is aging rapidly – a trend that causes the student population to shrink and threatens the existence of large numbers of Thai higher education institutions, particularly in the private sector. Some Thai education experts warned in 2017 that declining demand for education, combined with increased competition from foreign universities, could lead to the closure of as many as three quarters of higher education institutions over the coming decade [17].

According to the United Nations [18], Thailand is one of the world’s most quickly aging societies. The share of Thai people above the age of 65 has increased from 5 percent in 1995 to 11 percent in 2016, and is projected to reach more than a quarter of the population, or about 17 million people [19], by 2040. The working age population is consequently expected to drop by 11 percent, from 49 million people to slightly more than 40 million people [19] on 2040.

In light of this trend, it is important that Thailand stimulates immigration and upskills its labor force. Thailand currently has a relatively low-skilled labor force compared to other countries in the ASEAN community, and faces a severe shortage of skilled labor [20]. Far-reaching improvements in education are vital to overcoming this challenge and Thailand has invested heavily in modernizing its education system in recent years.

But the road to education reforms in Thailand has been rocky, as demonstrated by the fact that the country had no fewer than 20 different education ministers [21] over the past 17 years. Despite relatively high government spending on education since the military takeover in 2014, the military coup has interrupted important education reforms [22] and led to a change in priorities, after the previous government had pursued changes designed to internationalize the Thai education system, such as a relaxation of visa rules to attract more foreign teachers, the harmonization of qualifications and credit systems with ASEAN partner countries, and an increase of English-language programs in Thailand [23].

While the current government has put forward a number of reform initiatives, critics have contended that many of the initiatives have been somewhat superficial and primarily focused on promoting political stability. Recent reforms include, for instance, changes in school curricula [24] to incorporate “12 values” promulgated by Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, such as “correctly understanding democracy with the monarchy as head of the state, discipline and respect for the law and elders”. Other education reforms proposed by the junta will likely not be implemented until a new elected government takes office in 2018 [25] or 2019.

The OECD and UNESCO found in 2016 that Thailand’s “recent investments in education … are not resulting in the expected outcomes. The country’s results on international tests, such as the OECD [PISA study] … are below those of many peer countries; within Thailand there are significant disparities in student performance between socio-economically disadvantaged and advantaged schools and across rural and urban areas. (…) Thailand needs to continue to improve the effectiveness, efficiency and equity of its education system to ensure it does not fall behind other countries in this dynamic region”.1 [26]

International Student Mobility

Compared to other Asian countries like China, India or Vietnam, Thailand is traditionally not a big sending country of international students. The country’s outbound student mobility rate among degree seeking students has remained largely flat over the past 17 years and ranged from 1.2 percent in 1999 to 1.1 percent in 2006 and 1.3 percent in 2015 (UNESCO Institute of Statistics [27] – UIS), whereas Vietnam’s outbound rate increased from 1.0 percent in 1999 to 2.6 percent in 2015. While the outbound mobility rate is not necessarily a good predictor of total growth in outbound student numbers, Thailand’s growth rate is also relatively small in absolute numbers. Between 2002 and 2016, the number of outbound degree students increased by only about 10 percent, from 25,767 students to 28,339 students (UIS). In China, by comparison, the number of outbound degree students simultaneously grew by 256 percent, while the number of outbound students in Vietnam exploded by 422 percent during the same time period (from 12,197 to 63,703 students).

Not very much is known about Thai students’ motivations to study abroad, but international educators attribute outbound mobility in Thailand to common push factors, such as an increasingly affluent middle class [28], which is driving demand [29] for high-quality education, enrollment in prestigious international schools and foreign language training. With English language skills still being relatively underdeveloped in Thailand, the country now has the second highest number [30] of English-medium private international schools in the ASEAN after Indonesia, according to the International School Consultancy Group (181 schools in 2017 compared to just 10 international schools for expatriate children in 1992 [31]). Foreign education can also help to improve the employment prospects of graduates on the highly competitive Thai job market. The political instability in Thailand, likewise, is said to be a strong motivating factor [32] for study abroad. Mobile Thai students are mostly self-funded [33] – a fact that bodes well for a sustained outflow of students if the Thai economy continues to stabilize. It remains to be seen; however, if these push factors can sustain current outbound mobility levels in the face of declining student numbers [34] due to population aging in the years ahead.

Study Destinations

The U.S. has historically been the preferred study destination of mobile Thai degree students, and presently continues to be the most popular destination country, accounting for 25 percent of enrollments abroad in 2016 (7,052 students [35]), according to the UIS. The U.S. is followed by other English-speaking countries like the U.K. (6,246 students) and Australia (4,751 students), as well as Japan (2,256 students). Over the past decades, the market share of the U.S., however, has declined significantly in favor of countries like the U.K., where the number of Thai degree students almost tripled since 2002.

As per the Open Doors data [36] of the International Institute of Education, the number of Thai students in the U.S. dropped by 3.1 percent between 2015/16 and 2016/17, after already declining by more than 40 percent since 2001/02, when Thailand was the 10th leading country of origin with 11,606 students (it is currently ranked as the 27th leading country of origin with 6,893 students). Thai students are enrolled in undergraduate and graduate programs in equal parts. Business-related majors are the most popular field of study among Thai students. In Canada, the number of Thai students is relatively small and has been fluctuating over the past ten years. Thailand was the 37th largest sender of foreign students in 2015 with 790 students, according to the Canadian government [37].

Inbound Student Mobility

Thailand is the third most popular study destination in Southeast Asia after Malaysia and Singapore and attracts a far larger number of international degree students than Indonesia or Vietnam, for example. According to the data provided by the UIS [27], the number of international degree students in Thailand increased by fully 979 percent between 1999 and 2012, from 1,882 to 20,309 students. The vast majority of international students come from Asian neighbor countries, with China being the largest sending country by far. Surveys of Chinese students show that beyond standard academic considerations, Thailand is a popular study destination because of “the friendliness of the people, fundamental infrastructure, affordability, beauty of the environment, and safety [38]”. These factors likely also play a role in making Thailand a popular study destination among U.S. students, who prefer Thailand above all other countries in Southeast Asia. According to the IIE’s Open Doors data [39], the number of U.S. students almost doubled over the past decade from 1,128 students in 2004/05 to 2,093 students in 2016/17.

At the same time, inbound mobility to Thailand appears to be affected by the political developments over the past years. In 2014, the last year that UIS provides student data for Thailand, the number of inbound degree students dropped sharply by 39 percent to 12,274 students [27], very likely due to political instability and street protests that preceded the 2014 military coup. In the long term, however, Thailand’s popularity as a study destination may well increase. For some students from Asian countries like India and China, Thailand is a low cost alternative [32] to expensive destinations like the U.S. or Australia, and also offers a sizeable number international study programs and scholarship opportunities [40]. Trade liberalization, including the uninhibited flow of educational services, in the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) [41], a free trade area initiated in 2015, may in the future offer Thailand further opportunities to advance its competitive position as a study destination among Asian students [38].

In Brief: Thailand’s Education System

Thailand is among the few countries in the world that have never been colonized by European powers. Unlike in neighboring countries, Thailand’s education system therefore developed mostly indigenously, following its own trajectory. The country’s formal education system can be said to date to the late 13th century, when the Thai alphabet was developed under King Rakhamhaeng the Great. The aristocracy was educated in Royal institutions of instruction, while commoners could receive an education at Buddhist monasteries [42].

With the country’s growing integration into the world economy, Thailand has since the 19th century modernized its education system based on Western models, especially following the end of the absolute Thai monarchy in 1932. Many elements of the contemporary Thai higher education system in particular are modeled on the U.S. system of education, including the degree structure, credit system and general-education component in undergraduate curricula.

Today, Thailand is pursuing increased integration into the global education community, with an emphasis on regional partners (notably ASEAN partner countries). The number of collaborative programs between Thai and foreign higher education institutions is on the rise, and governments have emphasized internationalization of the Thai education system in recent years.

Administration of the Education System

Thailand is a constitutional monarchy in which King Vajiralongkorn [43], or Rama X (enthroned in 2016) functions as the head of state, while the government is presently run by a so-called “National Council of Peace and Order” under an appointed prime minister serving as the head of government. The country is divided into 76 administrative changwats, or provinces, the governors of which are appointed by the Interior Ministry in in Bangkok.

General education policy is under the purview of the national Ministry of Education (MOE), which oversees basic, vocational and higher education, with the majority of public (and private) education institutions falling under its remit. Specialized higher education institutions are the exception as they may be under the jurisdiction of other governmental departments, such as the Ministry of Public Health. A number of different government organizations under the MOE administer the different sectors of the education system: The “Office of the Basic Education Commission” (OBEC) oversees elementary and secondary education, (basic education), the “Office of the Vocational Education Commission” (OVEC) oversees vocational education and training, while higher education is under the purview of the “Office of the Higher Education Commission” (OHEC).

Reforms initiated in the late 1990s introduced greater decentralization of the – until then highly centralized – Thai education system, with local administrative units, the so-called Local Administration Organizations [44] (under the Ministry of Interior), being able to provide education at all levels of study according to local needs.

Educational Service Areas (ESAs), too, were established to further the goal of decentralization. ESAs are administrative units responsible for hiring teachers and implementing policy at the local level. There were 185 ESAs in 2008, each of them responsible for approximately 200 education institutions and 300,000 to 500,000 students [45].

As a result of the various decentralization efforts, administration of education in Thailand can now be complex with a variety of actors and overlapping responsibilities. That said, the current government in 2016 implemented changes that seek the re-centralization [46] of parts of the elementary and secondary education system.

The Academic Year and Language of Instruction

Presently, not all education institutions in Thailand follow the same academic calendar. The academic year used to start in June and end in March for all higher education institutions, but was changed in 2014 to coincide with the school year in other ASEAN countries. The ASEAN-based calendar, running from August to May, however, has been heavily criticized, mainly for keeping staff and students in overheated classrooms and lecture halls during the hottest months of the year in Thailand. Several higher education institutions were therefore allowed to revert to the old academic calendar [47] in 2016. Elementary and secondary schools generally still use the old academic year, so that there is a mismatch between secondary schools and some universities that continue use the ASEAN calendar.

The language of instruction is generally Thai, with the exception of a small number of private institutions and international study programs that use English as a medium of instruction.

Elementary Education

Compulsory education in Thailand covers the first nine years of “basic education” (six years of elementary school and three years of lower secondary school). Education at public schools is free of charge until grade 9. At present, the government also provides three years of free pre-school and three years of free upper-secondary education, neither of which are mandatory, however.

Children are enrolled in elementary school from the age of six and attend for six years (Prathom 1 to Prathom 6.) Admission is usually open to all children, but some prestigious schools may have entrance examinations, particularly in urban areas. Elementary school classes must not exceed five hours per day, with a maximum learning time of 1,000 hours per year [48]. The curriculum is set in the official “Basic Education Core Curriculum [49] of 2008” and includes Thai language, mathematics, science, social studies, religion and culture, physical education, art, occupations and technology, and foreign languages.

Pupils undergo two national examinations during their elementary school years. The first, which is administered by the Office of the Basic Education Commission’s Bureau of Educational testing at the end of Prathom 3, tests reading, writing and reasoning [25]. At the end of Prathom 6, elementary education concludes with the first of three Ordinary National Education Tests, set by the National Institute of Educational Testing Service (the other two tests are at the end of grades 9 and 12). The test covers the main subjects [50] of the Basic Education Core Curriculum (Thai language, mathematics, science, social studies, religion and culture and foreign languages). Upon successful passing of the exam, pupils are awarded a Certificate of Primary Education.

Lower and Upper-Secondary Education

Secondary education starts at the age of 12 and consists of three years of lower secondary education, called Mattayom 1 to Mattayom 3, and three years of upper secondary education, or Mattayom 4 to Mattayom 6. Compulsory education ends with Mattayom 3 (grade 9), after which pupils can pursue upper-secondary education in a general academic, university-preparatory track, or continue their studies in more employment-geared vocational school programs (discussed below).

In addition to general academic and vocational schools, there are “comprehensive schools”, which offer both general academic and vocational programs. Overall, 75 percent [25] of eligible youth were enrolled in upper-secondary school programs in 2013.

The formal minimum admission requirement for lower-secondary education is the completion of elementary schooling and the completion of lower-secondary education for upper-secondary programs, respectively. Beyond that, admission criteria for both lower and upper secondary education vary, but frequently include entrance examinations or lottery systems at schools with high demand. The competitiveness of admissions to prestigious schools has created bribery problems with parents paying so-called “tea money [51]” to ensure that their children get admitted into desirable schools.

General Academic Curriculum

The secondary school curriculum, like its elementary school counterpart, is set nationwide in the 2008 Basic Education Core Curriculum [49] and includes the same core subjects, even though the core curriculum has been under review since 2011, and reforms are expected in the near future. At both the lower and upper secondary level, pupils attend 1,000 to 1,200 learning hours per year. Pupils must take 41 credits in the core subjects in upper secondary, with one credit defined as 40 hours per semester: six credits each for Thai, mathematics, science, and foreign languages; eight credits for social studies, religion and culture; and three credits each for arts, health and physical education, occupations and technology. A further 1600 hours are allocated to additional courses and activities determined at the local level, which range from classes dedicated to teaching towards the O-NET examinations to subject areas not covered by the centrally prescribed portion of the national curriculum.

Promotion

Promotion to the next year is determined by examinations in each subject, with the standards to be met by pupils determined by the local school authorities. At end of grade 9 and grade 12, pupils are also assessed at the national level via the National Institute of Educational Testing Service’s Ordinary National Education Test (O-NET). The examinations cover the core subjects Thai Language, mathematics; science; social studies, religion and culture; and foreign languages at both the end of grade 9 and grade 12. Pupils who successfully pass the examination at the end of grade 9 are awarded the Certificate of Lower Secondary Education, also known as Matayom 3 or MS 3, whereas senior secondary school graduates are awarded the Certificate of Secondary Education (Matayom 6 or MS 6). O-NET examination scores currently account for 30 percent of the final Matayom 6 results, a criterion for university admission, but recent reform proposals seek to increase this to 50 percent or more [25]. Pass rates can be low and are geographically uneven, with students from Bangkok scoring significantly higher on average than students from rural regions. The 378,000 students that sat for the test in 2016 reportedly [52] only passed one out of five test subjects on average.

Pupils at religious high school institutions may be required to pass faith-based examinations. In the past, Buddhist temples were important providers of education, and faith-based education still plays a significant role in Thailand. Islamic schools, likewise, exist for Muslim Malays and other Muslim minorities. There are therefore national examinations specifically for pupils who follow a faith-based curriculum: the Islamic National Educational Test [53] (known as I-NET), which was introduced by the National Institute of Educational Testing Service in 2009; and the Buddhist National Educational Test [54] (B-NET), which was introduced in 2012.

Upper-Secondary Vocational Education

Thai governments have in recent years tried to increase enrollments in secondary vocational education and training (VET) in an attempt to develop manpower and upskill the labor force outside of university education. The Ministry of Education’s Strategic Action Plan 2005-2008, for instance, sought to increase enrollments in vocational programs to 50 percent [44] of all upper-secondary enrollments. It has been difficult for the government to achieve these goals in recent years, however. According to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics [27], the share of enrollments in the vocational track stood at 40 percent in 2007, only to drop to 34 percent in 2013 and further decline to less than 20 percent in 2015.

Upper secondary vocational education programs are overseen by the Ministry of Education’s Office of the Vocational Education Commission and are offered in wide variety of specializations, including industry; commerce/business administration; arts; home economics; agriculture; fishery; tourism and hospitality; textiles; and information and computer technology.

There are both entirely school-based programs and dual education programs that combine theoretical instruction with work-based training. School-based programs at vocational upper secondary schools are most commonly three years in length and lead to the award of a Certificate in Vocational Education, a credential which may also serve as an admission requirement to post-secondary education. Dual-track programs, on the other hand, place a greater emphasis on job readiness through partnerships with businesses. These programs lead to a Certificate in Dual Vocational Education following three years of education and training, divided between classes taken at school and practical training at companies. VET subject areas include trade and industry, agriculture, home economics, fishery, business, tourism, arts and crafts, and textiles. Secondary-level vocational students take the Vocational National Educational Test [55] (V-NET), which is offered in various subject areas, in their third year of study.

Non-formal and informal education

In addition to formal education in regular elementary, secondary and higher education programs, Thailand has a relatively sizeable system of non-formal and informal education. Non-formal education is defined as continuous learning and includes not just programs to increase literacy but also various types of secondary and post-secondary education that are delivered through modes such as distance learning and may have more flexible admission requirements. According to the National Statistics Office of Thailand [57], close to 3.4 million students took advantage of this type of education in 2016 at the elementary and secondary levels, compared to approximately 10.8 million students enrolled in formal basic education programs. Many non-formal education programs allow for credit transfer to the formal sector in order to encourage academic mobility. Students can, for instance, transfer from non-formal vocational programs into formal upper-secondary vocational education by taking the “Non-Formal National Education Test [58]” (N-NET), which tests subjects, such as computer skills, mathematics and languages.

Informal education, which, like non-formal education, is overseen by the Ministry of Education’s Office of Non-Formal and Informal Education, is a less structured form of education provided through libraries, radio programs and other non-teaching institutions. Informal education does generally not articulate into formal education programs.

Patterns in Elementary and Secondary Enrollment

Thailand has over the past decades made great progress in expanding participation in education. Net enrollment increased from averages of around 75 percent in the mid-1970s to around 95 percent over the past decade, even though net enrollment dropped to just under 91 percent in 2015 (the most recent year for which UIS data [27] are available). The youth literacy rate stood at 98.15 percent [59] in 2015 and the net enrollment rate in secondary education increased from 31 percent in 1990 to 78 percent in 2011 alone, according to the World Bank [60].

That said, progress has stalled in recent years and observers have noted persisting quality problems in Thai education. There are significant achievement gaps between children in urban and rural areas at all levels of basic education, and for some segments of the population, the costs of attending school (such as transportation) remain prohibitive, despite secondary-level education being free of charge and government loans [61] being available for both secondary and post-secondary study. Disparities in enrollment rates are therefore not so much between the sexes: female and male enrolment ratios at the elementary and secondary levels have been very close for the past decade. In fact, the proportion of girls has exceeded the proportion of boys in most years at both the secondary and tertiary level.

Access inequalities are instead linked to socio-economic factors: Poor rural populations and some of the country’s linguistic and ethnic minorities [25] and migrant communities [62] have markedly lower enrollment and graduation rates (particularly at the upper secondary level) compared to the population as a whole. Small rural schools have been identified by numerous reports2 [63] as contributing to this problem, partly because it is difficult for these institutions to hire and retain well qualified teachers. Teacher shortages in some subject areas further exacerbate the problem. The number of small schools reportedly increased significant between the early 1990s and 2010 [60], when almost 30 percent of schools had average class sizes of less than ten pupils [25].

These factors contribute to the fact that Thailand lags behind countries of similar level of economic development in the comparative international OECD “Programme for International Student Assessment” (PISA). In the 2015 test, Thailand ranked 54th out of 70 countries [64], below the OECD average, as well as far behind high-performing Vietnam. Thailand’s 2015 PISA scores in all three subject areas (science, reading, and mathematics) are lower than its test scores from 2000 [65], when the PISA study was launched.

Enrollments

Due to declining birth rates, total enrollments at all levels of education have been decreasing in recent years. According to the latest data provided by the National Statistics Office of Thailand [57], the number of upper-secondary students, for instance, dropped by more than 9 percent between 2012 and 2016, from 2.14 million to 1.94 million students. Higher education enrollments dropped by about 9 percent as well, from 2.56 million to 2.32 million students. This trend is bound to accelerate, as Thailand is expected to have the world’s fastest-declining population of 18-to-22-year-olds in the years ahead, with the college-aged population anticipated to shrink by about 20 percent between 2012 and 2025, according to ICEF Monitor. [34]

The private education sector is expected to be affected by this decline in particular [66] and the percentage of enrollments at private education institutions has already slightly decreased in recent years. In an increasingly competitive environment in which students have more choices, expensive, tuition-funded private institutions are more vulnerable to shifts in demand than public institutions, which can rely on public funding, even though there are also a number of private schools at the secondary level, such as Buddhist and Islamic faith-based schools, which receive public subsidies and per-pupil premiums from the government [44].

In upper-secondary education, the share of private sector enrollments dropped from 20.2 percent in 2013 to 11.3 percent [27] in 2015 (UIS), whereas enrollments at private higher education institutions have, thus far, been more stable and stood at 17 percent in 2015, compared to a high of 21 percent in 1999. Unsurprisingly, private education in Thailand is more prevalent among richer segments of society in urban areas [67], notably Bangkok, than among less affluent social groups in more rural areas.

Higher Education

University Admissions

The university admissions process in Thailand has undergone a number of changes in recent years, but is generally based on both the upper-secondary school GPA and results in standardized entrance examinations. That said, the system has over the past decades emphasized examinations, with high school performance usually playing a comparatively minor role in admissions. Between 2006 and 2017, most public universities utilized a ”Central University Admission System” (CUAS) that allocated students to universities and programs based on a score derived from the final high school grade average (20 percent) and the results from a series of three different exams [68]: the Ordinary National Education Test (O-NET) (30 percent), the General Aptitude Test (GAT) (10-15 percent) and the Professional Aptitude Test (PAT) (0-40 percent). Direct admission outside the CUAS was possible, but also dependent on adequate scores in standardized examinations.

Since 2018, Thailand introduced a new admissions process that seeks to improve students’ chances of admission and to make the admissions process more socially fair. There is now a Thai Central Admission System (TCAS) [69], utilized by 54 public universities. Direct university admissions, which had been criticized for disadvantaging applicants from families that could not afford the additional tutoring, examination fees and travel expenses involved, have now been limited [70], while the importance of examinations has been reduced in general. To prevent students from accepting more than one university place, thereby blocking places that they will not take up, the new admissions process will be staggered in five rounds. The first round is solely based on student records without any written examinations, but examinations like the O-NET, GAT and PAT are introduced in the following rounds. Direct university admission is only possible in the fifth and final round [71]. Private universities, meanwhile, can admit students based on alternative criteria.

Overall, university admissions have become less competitive in recent years, due to the dwindling number of students. Thai officials reported that in 2015, for example, only 105,046 students [72] applied to take entrance exams for 156,216 available university seats, leaving more than 50,000 places unoccupied. As a result, even top universities like Thammasat University are currently considering downsizing [73] their departments and programs. This is a vast difference compared to the shortages and access limitations of previous decades. In 1995, for example, there were only 45,727 university seats for 140,515 applicants [74].

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs)

The number of higher education institutions in Thailand has grown strongly over the past decades from just a handful of universities in the 1970s [75] to 156 officially recognized HEIs in 2015 [76]. Before student numbers started to decrease due to the demographic decline of recent years, this growth was driven by the rapid massification of education in Thailand. The number of students in Thai higher education exploded from less than 130,000 students in the early 1970s [74] to more than 2.5 million in 2012 [57]. Unsurprisingly, growing demand for education brought about a number of changes in the HEI landscape, such as the merger of smaller colleges [77] into larger universities and the emergence of private HEIs, mostly since the 1980s. Private HEIs accounted for 48 percent of HEIs (75) in 2015, even though their share of enrollments stood at only 17 percent.

There are a variety of different types of HEIs in Thailand, including multi-disciplinary research universities, specialized institutions (Buddhist universities, nursing colleges, or military academies) and community colleges offering short-term programs and vocational training courses. HEIs are heavily concentrated in Bangkok, where 30 percent [77] of HEIs were located in 2008. Since 2009, there are nine designated national research universities [78] that receive special funding and support to be developed into globally competitive universities. These include Chulalongkorn University, which was established as a university in 1917 and is considered to be the oldest university in the country.

There are also two Open Universities, Ramkhamhaeng University and Sukhothai Thammathirat Open University, which are large public universities that account for a considerable share of Thailand’s student enrollments and offer programs on various campuses throughout the country, as well as distance education programs. The Open Universities have comparatively low admission standards and were established in the 1970s to meet the growing demand for education in Thailand, particularly in rural regions. Ramkhamhaeng University is considered one of the largest mega universities [79] of the world.

Other types of public universities include the so-called “Rajabhat Universities”, a group of institutions that originated as teacher training colleges, but now have university status and offer a variety of degree courses beyond teacher training, including doctoral programs in some cases. These institutions are dedicated to the development of local communities [80]. “Rajamangala Universities of Technology”, similarly, are public universities that were upgraded from Institutes of Technology, but with a focus on science and technology.

In addition to fully publicly controlled universities, there are also several so-called “autonomous universities”. These are self-governing public institutions that began to appear in the 1990s. Unlike other public universities, which receive funding based on the number of enrolled students, autonomous universities receive block grants from the government. Furthermore, the institution’s finances and administration are overseen by the university council, rather than public officials.

Quality Assurance

The MOE’s Office of the Higher Education Commission (OHEC) is currently responsible for the funding and oversight of public HEIs, as well as the establishment of new institutions and closure of existing ones. Discussions are, however, underway to break the Office of the Higher Education Commission back out of MOE and re-establish it as a Ministry of University Affairs in order to centralize oversight and improve governance of the university system [81].

All post-secondary institutions, both public and private, are obligated to conduct annual internal quality assurance reviews, which are then externally audited by the OHEC at least every five years [82]. OHEC also reviews the approval processes for new degree programs offered by HEIs. An independent external quality review agency, the “Office for National Education Standards and Quality Assessment” (ONESQA [83]), is charged with assessing the quality assurance mechanisms of HEIs. Quality indicators for HEIs include the employability of graduates, research output, publications and contributions to the establishment of a knowledge-based Thai society and the development of local communities.

If institutions fail to rectify identified quality problems within a specified period of time, they are subject to closure. The closure of HEIs is under the purview of OHEC, which also maintains a directory of duly recognized public and private higher education institutions.

Internationalization

The internationalization of higher education is as evident in Thailand as it is in neighboring countries and around the world. Despite the political instability and lack of a strong governmental strategy to promote internationalization, collaborations between Thai and foreign universities has grown robustly in recent years, with the number of joint degree programs with foreign universities, for example, increasing from 92 in 2011 to 159 in 2013 [84] alone. In 2015, Thai universities offered 1,044 international programs [85] in English, according to the Australian government.

In a related development, foreign higher education institutions have in 2017 been given the green light to open branch campuses in Thailand – a move intended to modernize the education system and reduce skills gaps in Thailand. [86] To avoid direct competition with Thai universities suffering from declining enrollments, however, foreign institutions will only be able to operate in the country’s “special economic zones” and are not allowed to offer programs that are currently taught at Thai universities [86]. Critics nevertheless contend [87] that the move will increase competition and accelerate the closure of Thai universities caused by population aging.

Global University Rankings

Some observers see Thailand having great future potential as a global player in higher education [88]. In order to become internationally more competitive, however, Thai universities will have to increase their research output, which is still relatively low by international comparison. At present, Thailand does not yet have universities that are considered world class and the standing of Thai universities in standard global university rankings is still nascent. Mahidol University ranked at position 245 in the 2018 QS Ranking [89], Chulalongkorn University at position 334 in QS and position 401-500 in the 2017 Shanghai Ranking [90], while no Thai universities were included among the top 500 in the 2018 Times Higher Education World University Ranking [91].

Recent initiatives, such as the “National Research University Initiative and Research Promotion in Higher Education Project”, designed to strengthen Thailand’s national research universities and develop them into world class institutions, however, appear to be gaining traction. Between 2011 and 2016, Thailand’s research output, as measured by journal publications, increased by 20 percent [92], with Mahidol University, Chulalongkorn University and Chiang Mai University being the most prolific contributors.

Higher Education Degree System

As other ASEAN countries [93], Thailand is developing a National Qualifications Framework (NQF) to facilitate the comparability and transferability of qualifications within the ASEAN community. A draft Thai NQF was approved by the government in 2014 [94], but has not yet been fully implemented. It delineates 9 levels of education, from lower-secondary to doctoral education, somewhat similar to the system of education in the United States. In higher education, a set number of credit units are associated with different credentials – the credit system is a U.S. style system with a standard academic course load of 30 credits per year at the undergraduate level.

The vast majority of Thai students study at the undergraduate level. In 2015, 2.14 million students were enrolled at the bachelor’s level or below, while only 180,418 students [57] pursued graduate studies above bachelor’s level.

Associate Degree and Diploma Programs

First entry-level degree programs in Thailand are commonly two years in length (60 credits), but may also be three years (90 credits) in length, depending on the program. Associate of Arts or Associate of Science programs are studied at colleges, institutes of technology or universities and usually require the Certificate of Secondary Education or the Certificate of Vocational Education for admission. Holders of associate degrees with high enough grades may be granted exemptions of up to two years when continuing their studies in bachelor’s programs.

In addition to associate degrees, there is a variety of less formalized diploma programs being offered at Thai colleges and universities. These are offered in a number of different majors are most often two years in length after the Certificate of Secondary Education or the Certificate of Vocational Education.

Bachelor’s degrees in standard academic disciplines are generally four years in length (120 credits). The minimum GPA for degree conferral is 2.0 (C). The curriculum includes a combination of general education courses (usually 30 credits), compulsory subject-specific courses and electives. The most common admission requirement is the Certificate of Secondary Education, but there are alternative entry pathways based on previous qualifications, such as an associate degree or a diploma.

Graduate Education

Graduate diplomas are short-term graduate programs that typically last two semesters (24 credits at minimum). The standard admission requirement is a bachelor’s degree and programs are designed to offer specialized training in professional disciplines – a common major for these credentials is teaching, for example (see also the Teacher Education section, below).

Master’s degrees take at least one year of study to complete and require a minimum of 36 credits, but are most often offered as two-year programs. Admission requires a bachelor’s degree with good grades (often a minimum GPA of 2.5 or 3.0). Master’s degree conferral is dependent on a minimum GPA of 3.0, as well as satisfying the coursework requirements and completing a thesis or passing an examination. Master’s degrees are classified as research degrees (Master of Arts and Master of Science) and professional degrees, such as the Master of Business Administration, Master of Engineering or Master of Education. Research master’s degrees typically require the writing of a thesis, whereas professional master’s degrees may be earned by coursework only or a combination of coursework and completion of a project. Course work-only degrees usually require a higher number of credits for completion (typically 45-55 credits).

Higher graduate diplomas are awarded only in professional fields, mainly in medical disciplines and clinical sciences. The admission requirement is generally a first professional degree, such as a Doctor of Medicine, Doctor of Dental Surgery or similar. The number of credits varies by field and institution, but a minimum of 24 credits is usually required.

Doctoral degrees represent the highest academic credential in Thailand. Programs typically require a dissertation in addition to mandatory coursework. The credit requirements depend on whether students are admitted on the basis of a bachelor’s degree or on the basis of a master’s degree: in the former case, students are required to complete a minimum of 72 credits, whereas master’s degrees holders will need to gain only 48 credits to qualify. Doctorates are classified as either academic (Doctor of Philosophy) or professional (such as the Doctor of Engineering), but both require the submission of a thesis. The duration of doctoral programs is typically three years at minimum. Admission is generally reserved for top students.

Professional Education

Most first professional degree programs in Thailand are long single-tiered programs entered directly after upper secondary school. Some programs, like those leading to the Bachelor of Laws and Bachelor of Architecture degrees, are four and five years in length, respectively, but programs in medicine, dentistry, veterinary medicine, and pharmacy require six years of study (a minimum of 180 credits).

Medicine is studied at the faculties of medicine of one of the 19 public and 2 private institutions authorized [96] by the Medical Council of Thailand. The six-year program leads to the award of the Doctor of Medicine and has to consist of one year of pre-medical education (basic sciences) and two years of pre-clinical studies, followed by three years of clinical education, according to the official curriculum guidelines [97] of the Medical Council. After satisfying the program requirements and completing a clinical internship of at least one year, graduates must pass the licensing examination administered by the Medical Council. Training in medical specialties requires an additional three to five [98] years of graduate medical education, depending on the specialty.

Similarly, the practice of dentistry is regulated and overseen by The Dental Council [99]. High school graduates can apply to registered higher education institutions whose dental programs have been certified by The Dental Council for the six-year Doctor of Dental Surgery program. As in clinical medicine, the dentistry curriculum combines theoretical instruction and clinical training. Postgraduate dental study includes master’s degrees and research-only doctorates.

Law is offered as a four-year undergraduate program and leads to the award of a Bachelor of Laws degree. After a further two years of postgraduate study, a Master of Laws can be awarded. According to the Lawyer’s Act of 1985 [100], applicants must have Thai nationality and must have been awarded at least an associate degree or bachelor’s degree in law to register and receive a license from the Lawyers Council [101].

Teacher Education

Until recently, teacher training programs were taught exclusively at dedicated teacher-training colleges, the former Rajabhat colleges, which have since been upgraded to universities. Nowadays, aspiring teachers can enroll in teacher training programs at wide variety of universities. Since the mid-2000s, Thailand has had a formal licensing process that requires teachers to hold an educational qualification accredited by the Teachers’ Council of Thailand [102] and have completed one year of in-service training at a school, at minimum.

A five-year Bachelor of Education degree is the standard academic prerequisite for teachers in Thailand at all levels of education. Programs usually include four years of coursework and one year of practice teaching. In addition to taking general pedagogical courses, students specialize in teaching a particular level or mode of education (such as elementary education or special education). Those preparing to teach at the secondary level specialize in a particular subject area. Alternatively, holders of a bachelor’s degree in a standard academic discipline can obtain a teaching qualification by earning a “top-up” graduate diploma in teaching, which involves one year of practice teaching and a number of pedagogical courses, concluding with a final examination.

Post-secondary VET

A variety of options for VET exist at the post-secondary level in Thailand, both in formal and non-formal education. In the non-formal sector, students can enhance skills and employability through short-term programs and distance education. These programs usually don’t have formal academic admission requirements and create lifelong learning opportunities throughout the country.

In the formal sector, students can pursue VET in vocational certificate and diploma programs at colleges or universities. A number of options exist [45] for the transfer and recognition of study and occupational training from both the formal and non-formal sectors. Most commonly, holders of vocational or technical education diplomas of two years or longer may gain entry into a bachelor’s programs in a related field, in which case the length of the bachelor’s program may be shortened to two years.

Formal diploma programs last two or three years, require the Certificate of Secondary Education or the Certificate of Vocational Education for admission and are offered in in fields of study, such as of commerce, industry, business administration, home economics, agriculture, fishery, tourism and hospitality, textiles or and information and computer technology [48].

Documentation Requirements

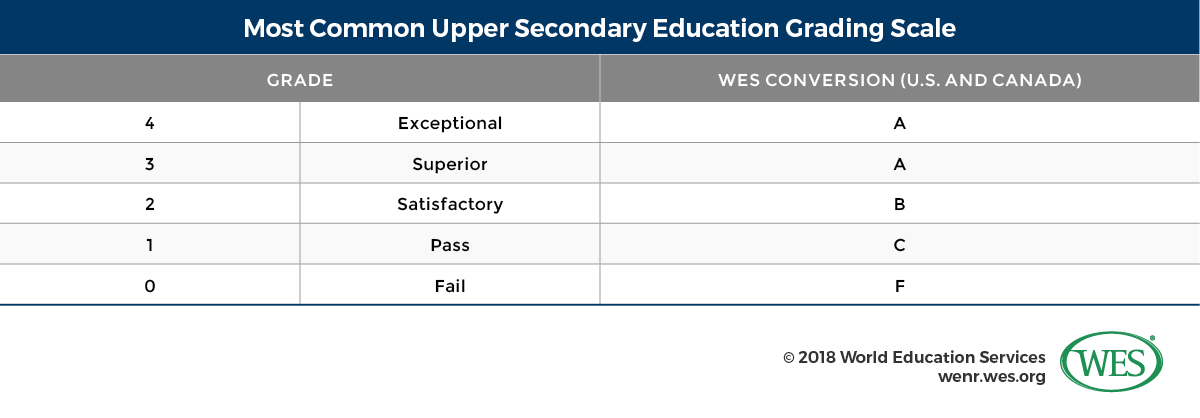

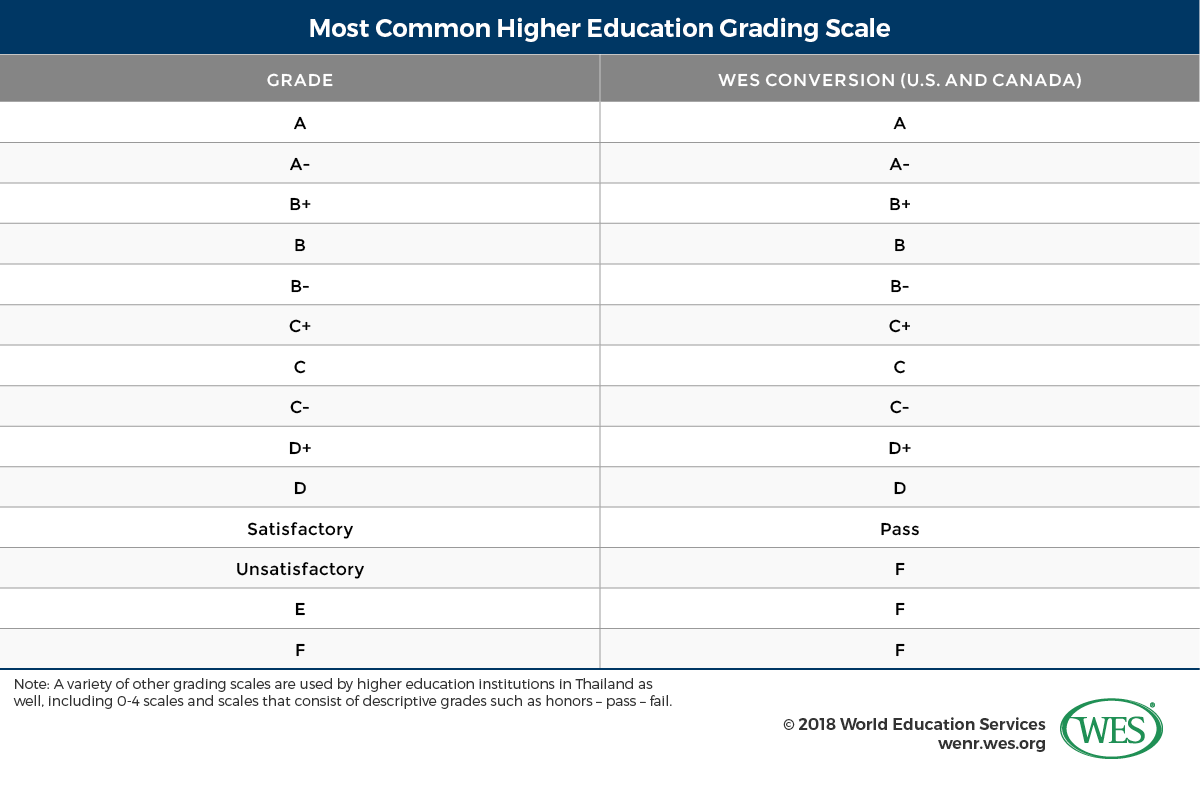

Thai institutions commonly issue documents in English. WES requires the following documents:

Secondary Education

- Official academic transcript issued in English – sent directly by the institution attended

Higher Education

- Official academic transcript issued in English – sent directly by the awarding institution

- For doctoral degrees – a letter confirming the conferral of the degree sent directly by the awarding institution

Sample Documents

Click here [103] for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Certificate of Secondary Education

- Bachelor of Economics

- Graduate Diploma in Teaching

- Master of Science

- Higher Graduate Diploma

- Doctor of Medicine

- Doctor of Philosophy

1. [104] OECD/UNESCO (2016), Education in Thailand: An OECD-UNESCO Perspective, Reviews of National Policies for Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, p. 19.

2. [105] See for example the assessment of the World Bank [106].