Bryce Loo, World Education Services; Bernhard Streitwieser, George Washington University; Jisun Jeong, George Washington University

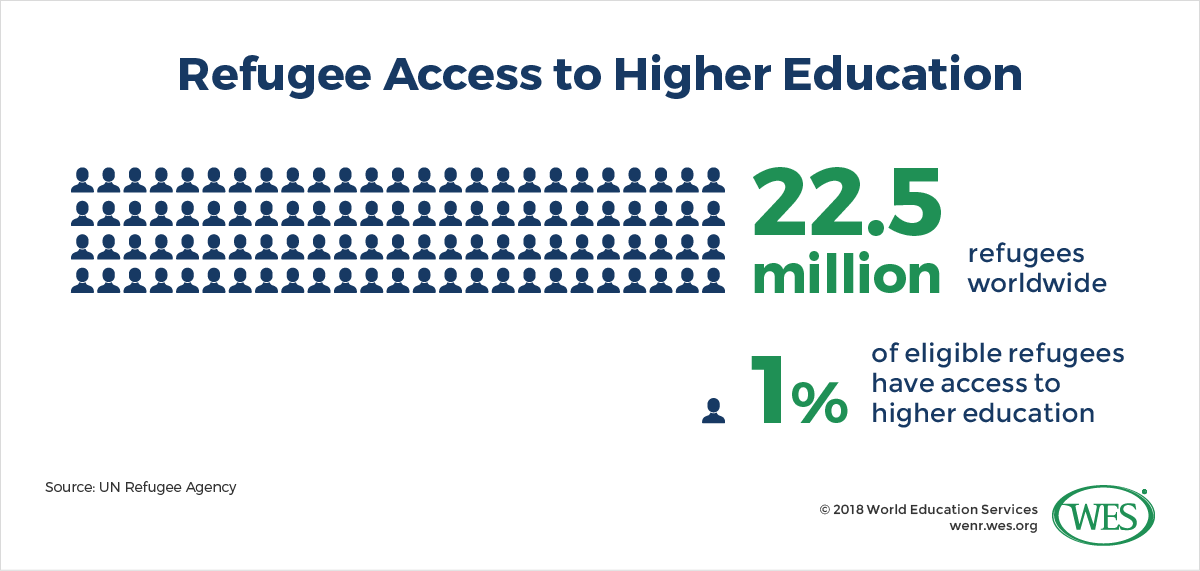

Not since the end of the Second World War have there been as many globally displaced people as there are today. By now, there are 22.5 million [1]refugees worldwid [1]e – 5.5 million [2] from civil-war-torn Syria alone – who have fled conflicts in the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

While most refugees shelter in neighboring countries in developing regions in the hope of returning home quickly (i.e., 84 percent [3]of the world’s refugees settled in developing regions in 2016), some also search out permanent resettlement further away.

Europe is the primary target for most mobile refugees from the MENA region, as well as Sub-Saharan Africa, though some refugees have managed to emigrate or resettle as far away as North America.

We will examine four countries in North America and Europe – Canada, the United States, Sweden, and France – as places that are rich in financial and social resources, innovating many of the current interventions helping refugees, and hosting a notable segment of the global refugee population that seeks access to its wide diversity of educational institutions.

We will discuss the political and social contexts of each country and how each higher education system (and some individual institutions) has responded to the influx of refugees and asylum-seekers. Then we will look at the common challenges faced and the practical efforts that the higher education community can undertake — UNHCR statistics indicate that only 1% [4]of refugees will eventually find their way into higher education, what is being done to change these numbers?

[5]

[5]

Canada

Political and social context

In many ways, Canada stands out among Western nations in its treatment of immigrants and refugees and their integration into society. Canada, like other major Western nations, has a history [6] of taking in large numbers of refugees from all over the world. But perhaps more than in any other Western country, multiculturalism is often seen as a key marker of Canadian identity [7]. This orientation is even enshrined into law through the Canadian Multiculturalism Act [8] of 1985. Because of this, Canada has largely avoided [9] many of the major socio-political problems stemming from xenophobia and nativism in many European countries and the United States, even in the wake of large-scale immigration and refugee resettlement. That being said, there is a small but growing number of racist and xenophobic voices – particularly Islamophobic voices [10] – within Canada, some of which are appearing on Canadian university and college campuses [11].

Canada’s refugee resettlement system in many ways reflects Canada’s commitment to multiculturalism. The most unique feature is that aside from government-sponsored refugee resettlement, the country also has a private sponsorship program for refugees [12]. Through this program, Canadian organizations ranging from businesses and non-profit organizations to civil society organizations, such as churches, may sponsor one or more refugees or refugee families. Additionally, a group of at least five Canadian citizens – known as a Group of Five (G5) – may sponsor an individual or family. The sponsoring organization or group agrees to sponsor the refugees for at least 12 months or until they are self-sufficient, and provides for all of their needs. This unique program has allowed ordinary Canadians to develop a stake [13] in the resettlement and integration of refugees.

Policy responses to the refugee crisis

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau campaigned on the promise [14] that the Liberal Party would ramp up resettlement of Syrian refugees. Upon his election, Trudeau promised to resettle up to 25,000 Syrian refugees by the following February. The government, in fact, was able to resettle well over 25,000, many of them privately-sponsored. As of the end of January 2017, over 40,000 Syrian refugees have settled in Canada, according to government statistics [15]. The Syrian crisis has particularly galvanized a large number of Canadians to become involved. Over 14,000 [16] of the over 40,000 Syrian refugees resettled to Canada are privately sponsored. And of particular importance to higher education, privately-sponsored refugees are usually more highly educated. Our analysis of data from Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) [17] found that 25 percent of privately-sponsored Syrian refugees have at least some university education, compared with only 2 percent of government-sponsored refugees, as of October 2017. The focus of refugee resettlement has been heavily on Syrians (and not without controversy and criticism [18]), but others – such as Eritreans, Iraqis, and Congolese [19] – have also been resettled, albeit in smaller numbers.

Higher education responses to the crisis

Canada has long had an apparatus in place for helping refugees access Canadian higher education in the form of the World University of Canada (WUSC) [20], a non-profit organization that has been in existence in various forms since the 1920s [21]. Since 1978, WUSC’s Student Refugee Program (SRP) [22] has placed refugee students from various locations around the world into Canadian universities. WUSC is a Sponsorship Agreement Holder (SAH), which allows the organization to resettle refugee students permanently in Canada, as part of the private sponsorship program. Participating universities then provide resettlement services on behalf of WUSC and work to integrate the refugee students on campus. They agree to fund the refugee students for the duration of their programs. Two things are particularly notable about the program: One is that students are heavily involved, usually in the form of local committees, which secure or raise the funding for the refugees, as well as assist in the resettlement and integration processes. The other is the funding scheme. Universities can fund the students in a variety of ways, but one notable way is through student (and sometimes faculty) levies, which are nominal fees added to student tuition bills, of which students can usually opt out.

Today, the program supports about 130 students each year. Refugees are resettled largely from camps in Kenya, Malawi, Lebanon, and Jordan, but the program has supported students from “39 different countries of origin and 37 different countries of asylum.” [23] Recently, WUSC-SRP has responded to the Syrian crisis [24] in particular: “In September of 2015, we partnered with Universities Canada and Colleges and Institutes Canada, to reach out to over 200 post-secondary academic institutions across the country. We challenged them to implement or increase their support of the Student Refugee Program on their campus. Thanks to the commitment of students, faculty and staff at these institutions, the response was – simply put – tremendous.”

Most of the response of Canadian higher education institutions to the recent refugee crisis, and other waves in the past, has been through WUSC-SRP. The students of the University of Calgary [25], for example, voted in 1986 for a levy to fund refugee students through the program. Today, the university sponsors two students every year through the program and has sponsored 32 students to date. Each sponsored student receives roughly CA$56,000 in tuition and other aid for the duration of a four-year academic program. Currently, WUSC lists [26] 65 partner institutions throughout most provinces and territories on its website. This is a remarkable number considering that there are roughly 200 degree-granting higher education institutions [27] in Canada. The list includes some of Canada’s top universities, including the University of Toronto, the University of British Columbia, and McGill University.

There are some other scattered efforts among institutions, but most are services other than direct access to universities and colleges. One is by simply helping in the resettlement process, unattached directly to higher education access. For example, Ryerson University in Toronto has partnered with Lifeline Syria [28], a community organization started in 2015 to help Syrian refugees settle and integrate into the Toronto area. The university established the Ryerson University Lifeline Syria Challenge [29] with the goal of raising money to sponsor and support ten Syrian families, and as of November 2017, they had raised CA$4 million and helped resettled 15 families. OCAD University, the University of Toronto, and York University have also joined.

The United States

Political and social context

The U.S. has been actively resettling refugees since the end of the Second World War [30]. The country has historically been the top host of resettled refugees [31] (i.e., refugees selected by the host government to be resettled in country) among wealthy countries. The U.S. still accepts a fair number of asylum-seekers, with over 26,000 granted asylum in fiscal year 2015 [32], although some groups have been somewhat controversial. For example, in 2014, there was some public backlash [33] to the arrival of huge numbers of Central American refugees, including a significant number of unaccompanied minors, fleeing gang violence and political instability, via Mexico.

Over time, Americans have become increasingly polarized over the issue of immigration, and in particular over refugees. Data from the Pew Research Center [34] show that Americans are split over support of immigration along partisan and generational lines, with Democrats and younger Americans, particularly Millennials (adults born from 1980 on), much more supportive of immigration and immigrants than Republicans and older Americans. Similarly, views on refugee resettlement in the U.S. also break down along partisan and generational lines. In a 2016 survey conducted by the Brookings Institution [35], 36 percent of Democrats strongly supported the idea of bringing in Middle Eastern refugees after receiving security screenings, while only 10 percent of Republicans and 24 percent of Independents did. On the flip side, 43 percent of Republicans strongly opposed bringing in Middle Eastern refugees (after security screening), versus only 8 percent of Democrats and 26 percent of Independents.

Policy responses to the refugee crisis

In early 2016, the Obama Administration pledged to take in 10,000 Syrian refugees [36]. Almost immediately, this pledge met stiff resistance from many sides. Many mostly Republican governors [37] said that they would refuse to resettle Syrians within their states, citing security concerns. Nevertheless, despite initial struggles to vet these refugees in time to meet the goal, the Administration was able to do so [38]. According to the [39]Washington Post [39], a total of 12,500 were actually resettled. President Obama then promised that the U.S. would take in around 110,000 Syrians in 2017, just as the 2016 presidential election heated up.

President Donald J. Trump campaigned on the promise to restrict immigration and refugee resettlement [40] in the U.S. Shortly after entering office, Trump announced a travel ban via executive order [41], which barred citizens from six Muslim-majority nations from entering the U.S. and temporarily suspended the refugee resettlement program. This met an immediate backlash from protesters and many states. Several states – including Hawaii, Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, and Washington – sued [42] the Trump Administration, and several federal courts put a stop to the travel ban. After multiple revisions, in December 2017 Trump was able to gain U.S. Supreme Court approval [43] for a travel ban for eight nations, six of which are predominantly Muslim, including Syria. Additionally, the administration has announced a cap of 45,000 for refugee resettlement, the “lowest number in years,” as NPR reports [44].

Syrians are actually not the top group resettled to the U.S. More Congolese and Iraqi refugees were resettled [45] than Syrians in fiscal year 2017. Burmese, Somali, and Bhutanese refugees have also been resettled in large numbers in recent years.

Higher education responses to the crisis

Higher education in the United States, along with most other institutional facets of life, is highly decentralized, and likewise, efforts to address the refugee crisis in the U.S. have also been very decentralized and somewhat fragmented. Nevertheless, important strides have been made. Perhaps the organization doing the most to take up the cause is the Institute of International Education (IIE), a large non-profit international education organization headquartered in New York City and Washington, DC. In response to the Syrian crisis, IIE started the Syria Consortium for Higher Education in Crisis [46], a network of U.S. and some international institutions committed to accepting and funding at least a few Syrian students each year. One of the member institutions that hosted the most Syrian students was the Illinois Institute of Technology, [47] which took in and funded 43 Syrian students between fall 2012 and fall 2016. IIE also partnered with the Catalyst Foundation for Universal Education and created the Platform for Education in Emergencies Response, known as IIE Peer [48] for short. IIE Peer provides a database of various higher education opportunities in the U.S. and elsewhere for Syrian refugees, with the eventual goal of including other refugee groups. Additionally, IIE’s president, Allan Goodman, has written and spoken extensively on the topic of refugee access to higher education worldwide in recent years, including in a piece for the Brookings Institution [49]. In particular, Goodman has advocated for the world’s universities to host at least one Syrian student or scholar.

Elsewhere, there are other smaller-scale initiatives, often focused on specific groups. In particular, Syrian refugees are the main group of concern, as is the case with IIE. Scholarships are a major focus and are sometimes student-initiated or led. For example, a student at the University of California (UC), Irvine, managed to fundraise for a new scholarship [50] for a Syrian refugee, using an initial grant as a starting point. Several non-profit organizations, notably Michigan-based Jusoor [51] and Books Not Bombs [52], have started to either give scholarships (in the case of the former) or enable students to petition for the creation of university-based scholarships (in the case of the latter). Both organizations were started in the wake of the Syrian crisis and work or advocate in multiple countries of asylum and resettlement. The student-driven scholarship from UC Irvine was aided by Books Not Bombs.

Some U.S. institutions have also coordinated efforts to help refugees in various ways other than by direct access to higher education. For example, Every Campus a Refuge [53], founded by Diya Abdo, a professor of English at Guilford College in Greensboro, North Carolina, advocates for higher education institutions to host refugee families on campus. So far, Guilford College has hosted 32 refugees.

Sweden

Political and social context

Sweden has long been a model of generosity [54] and efficiency accepting migrants and refugees into its society [55] and historically been more welcoming than other European countries. According to the UNHCR [56], Sweden is the largest donor of un-earmarked funds, in 2016 giving 815 million SEK (US$97 million) to the UNHCR to use at its discretion. Even though Swedish voters are no more concerned about the prospect of increased terrorism than citizens of other EU countries, according to a Pew Research Center study [57], 57% felt refugees would increase the likelihood of terrorism [58], and 46% felt refugees were more likely to blame for crime than other groups. At the same time, Swedes also view the growth of diversity within their society more favorably than do average Europeans, with 36% agreeing that newcomers make Sweden a better place to live, and 88% disapproving of how the EU has been handling refugees.

Policy responses to refugee crisis

In 2015, according to the Swedish Migration Agency [59], more than 160,000 refugees sought asylum in Sweden, twice the number who had come during the previous migration stream caused by the Balkan crisis in the early 1990s. That same year the Swedish Migration Agency [60] agreed to increase the number of resettled refugees to 5,000, however, the ensuring refugee stream led to a fivefold increase [61] in asylum claims between January and December. By the end of 2015 the worsening Syrian Civil War resulted in 10,000 entering Sweden per week [62], a figure expected to add the equivalent of 2% to its population of 9.9 million. This administrative backlog led to quickly implemented [61] but major policy changes [63], which included tighter border checkpoints, reduced services to make Sweden less attractive for refugees, but ramped up support for asylees already in country to help integrate [64] them more quickly.

While in 2015 Germany received the largest numbers of refugees in absolute numbers, Sweden received the largest per capita: 5.3 migrants per 1000 persons. However, asylum applications again significantly decreased and by 2017 were down to a mere 20,000, according to the Swedish Migration Agency [65]. In Sweden, 18.3% of the population is now foreign-born but the country’s traditional openness [66] to migrants has changed. Under pressure to enforce tougher immigration laws, the Swedish Social Democratic party shifted its traditional left-leaning stance more toward the center-right [67], giving an opening to the anti-immigration Sweden Democrats party, which now, at least according to recent polling [68], would attract more than one fifth (23.9%) of Swedish votes if an election were held today.

Higher Education Responses to the crisis

As of an October 2016 survey [69] of Swedish higher education institutions by the Association of Swedish Higher Education (SUHF), among 27 who responded about their activities related to refugees (of 40 total universities in the country), nearly half (48%) had already established a dedicated staff position to deal with recognition and validation of foreign learning certificates. In addition, refugees also receive language training support. While 14,675 licenses have been allocated broadly for such training throughout Sweden, 13,765 licenses have gone directly to higher education institutions.

Some Swedish universities are offering generous bridging programs, which include a wide host of support measures, from language training to invitations to audit lectures, to information seminars on issues related to navigating Swedish society, to integration facilitated through sporting activities. Umeå University [70]in the eastern part of the country offers fast track bridging programs for refugee academics to help them assimilate into the university and society. The University of Gothenburg [71] provides free services for language studies and tests, called Online Linguistics Support [72], a mentoring program called “University friend” [73] to match student mentors with mentees of refugee backgrounds, and a training program to support refugees finding a job on the Swedish labor market and positions for guest researchers. At many universities, language training is supported through a variety of modules, forums, tutoring sessions, and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), all part of the EU’s Erasmus+ Programme [74] supporting integration of refugees. Stockholm University [75] offers free online courses in the STEM fields and has also helped academics secure work. For some time early in the refugee crisis in 2015, students and members of the Malmö community formed the Ma [76]lmö University for Refugees [76], which offered seminars focused directly for refugees, a weekly Swedish Language cafe, and a Red Cross fundraiser. Finally, several Swedish universities have partnered with the Scholars at Risk [77] network to promote the integration of refugees, particularly for employment.

As in other European countries such as Germany and France, the main barrier [78] that refugees in Sweden face accessing higher education [79] is the difficulty of the language [80], which is required for study at university level. But the development of “sprint” and “startup” [61] language schools has addressed that challenge to some degree. But for some, the language hurdle, in addition to the administrative challenges of navigating the asylum process before they can even get to credential evaluation and subject matter competency testing, is too great and they either leave Sweden, transition to another line of work, or altogether abandon their dreams [81] of university studies.

France

Political and social context

Historically, France has been one of the leading countries that adopted assimilation [82] as a policy towards immigrants and refugees, often rejecting the retention of an ethnic identity to be perceived as “French.” This French model of immigration has been also known as “Republican model of integration1 [83]”, with which French common norms and values are based on sharing of memory, history, and sentiments; as a result, any sense of belonging to another country has generally been perceived as weakening an individual’s sense of being French [82]. Yet, the nation’s largest survey ever conducted for ethnic minorities in 2008 and 2009 rebukes the widespread belief and finds that as the share of dual nationalities grew significantly in recent years, the relationship between French national feeling and loyalty to the country of origin is complementary than a zero-sum [82].

In 2017, France received a record-high 100,412 [84] asylum applications, and a considerable increase of the requests were Albanian and West African nationals. Acceptance rates of the asylum applications vary significantly by countries of origin. In 2016, out of total 85,244 new asylum applicants, around 22 percent were granted refugee status and 12 percent subsidiary protection. Syrians had the lowest rejection rate at 2.8 percent while Haitians had the highest rejection rate at 95 percent.2 [85] Out of the total 18,555 newly accepted refugees in 2016, Syria, Sudan and DRC (Democratic Republic Congo) [86] were the top three countries of origin.

Policy responses to refugee crisis

France has been less open and engaged [87]in dealing with the Europe’s immigrant and refugee crisis, often compared to its neighbor, Germany. Compared to Germany, Sweden and Britain, the country has more often been seen as a country of transit than a destination [88] for the resettlement. Major terrorist attacks in France have been used by far-right movements to raise anti-immigration sentiments, which was evident in a Global Attitudes Survey [89], where 60% of the political right said that refugees are a major threat when only 29% said so on the left. Persistence of ethnic discrimination and xenophobia in France has been a real issue. France’s official banning of wearing Muslim scarve [90]s in schools has been controversial. In 2015, France ranked the lowest [91] out of the 41 countries tested for OECD’s PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) when immigrant students were asked about their sense of belonging at school.

There is some hope since Emmanuel Macron’s victory in the presidential election in May 2017 and that the new government is currently drafting its new immigration policy [92]. The government announced that France would remain open to people fleeing “war and persecution” but would draw the line at migrants entering France for “economic reasons.” One of the critical features of the new legislation is the expected shortened asylum application process to 6 months [93].

Higher education responses to the crisis

There is no government-led or coordinated initiative to grant refugees access to higher education. Refugees are considered the same as other international students [94]. However, Campus France [95] – the French agency for the promotion of higher education, international student services, and international mobility – has facilitated the access to higher education for refugee students by implementing a scholarship program [96] funded by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Development. The scholarship provides a monthly scholarship allowance, together with other benefits, for a duration of 1 to 3 years for Syrian refugee students living in Lebanon since 2016. Thirty-four Syrian students living in Lebanon were selected to study in higher education institutions in France during the 2016-2017 school year.

Several higher education institutions in France have been active in supporting refugee students. In France, a B2 level (intermediate) or higher French language proficiency [97](Diploma in French Language Study or DELF) is required to register for a university degree. Although there are no official data on refugee students’ French proficiency upon their arrival to France, the language barrier has been noted as one of the most important challenges in France.3 [98] As of June 2016, 21 AUF (Francophone University Association) initiatives [97] were selected in supporting students with the French language, credential support, scholarship, or other broader integration support services to the university campus. Individual universities also stood up to support refugees. Since September 2015, Université Paris 1-Pantheon-Sorbonne [99] has implemented a specific 12-week integration program for refugee students, which has benefitted 140 students so far. Another 170 are expected to benefit. The University of Strasbourg [100] is another exemplary higher education institution. The university will exempt tuition fees and provide students with French proficiency below C1 to enroll in a University Diploma in French as a Foreign Language or in a B2-level DELF (Elementary Diploma of French) for refugees or asylum-seekers from the Middle East. The University of Grenoble [101] has also been active in supporting refugee students since 2015. In 2016, the university designed a specific four-month university degree called “Passerelle Solidarité” (Solidarity Link), which is composed of French language and culture programs, and serves as a preparatory diploma in accessing higher education opportunities for refugee students.

What can be learned?

Most major Western countries are grappling with how to integrate a large number of resettled refugees and asylum-seekers from the Middle East, Africa, and elsewhere. There is no doubt that higher education is an important part of integration solutions. However, the social and political contexts within which higher education systems and institutions operate also play an important role. Canada’s relative openness to people from around the world, and the national mobilization to help Syrian refugees in particular, is paralleled to an extent in its higher education system. A large number of Canadian institutions, with the help of students and faculty, have sponsored and integrated many refugee students. Meanwhile in the U.S., there are tremendous but uneven efforts, perhaps mirrored by the broader divisions in American society over refugee resettlement and immigration. Sweden and France appear to have similar, growing divisions in public sentiment over refugees, particularly driven by political movements. In Sweden, the traditional generosity seemed to have reached a tipping point in late 2015, while in France refugees have neither found an open door nor a completely closed one, but terrorism blamed on migrants [102] has not made the mood friendlier. Each higher education system is aided or constrained – often at the same – by the broader socio-political environment in which it operates.

There are some notable commonalities in terms of challenges [103] among these four higher education systems when it comes to integrating refugees. One is cost. All four systems of higher education have associated costs associated with them, from the highest fees for all students in the U.S. to minimal fees [104] for international students in Sweden, which students must pay in addition to living costs. For refugees, higher education in wealthy societies is often prohibitively expensive. Institutions and organizations working on including refugees need to address this topic, and consequently, provide scholarships to many institutions and higher education organizations. It is less clear the extent to which institutions in these countries focus on integrating the students once on campus.

The second major issue is language. Many refugees will come from countries that are not predominantly English- or French-speaking. That being said, English and French are two of the most common foreign languages of study around the world, including in Syria, so many refugee students may come already knowing at least some of one of these languages. Swedish higher education, which generally requires some knowledge of Swedish for admissions purposes, may be at a disadvantage in that regard, but allowing refugees to access English-language programs while concurrently enrolled in Swedish language programs will help. In all cases, for refugee integration to succeed it is important for institutions in all hosting countries to think through how to best support students on the language challenge.

In all four countries, efforts by individual universities and colleges to admit and integrate refugee students are uneven. Some institutions work actively to provide scholarships and support to refugee students, while others only work on a case-by-case basis when refugees show up at their door. One practice that seems to help is to have a national-level organization coordinate efforts among institutions. The World University Service of Canada (WUSC), the Institute of International Education (IIE) in the U.S., and Campus France appear to be taking up these roles to varying degrees. These organizations can and often do provide support to institutions in terms of best practices, country expertise, information-sharing, and even simply encouraging assistance to refugees.

WUSC, and Canada in general, particularly stand out. A significant proportion of Canadian higher education institutions appear to sponsor refugees through WUSC’s Student Refugee Program (SRP). In particular, WUSC’s long history in Canada and their ability to channel the energies and the passion of local students seems to help spur Canadian universities and colleges to stay actively involved in helping refugees. The expertise and infrastructure that WUSC also provides to institutions in terms of selecting and sponsoring refugee students helps take some of the burden off of institutions. This is potentially a model that major organizations in other countries could adopt and adapt to their national contexts. In any case, coordination and collaboration among institutions, usually with the help of a major higher education organization, can make a big impact.

The focus of WUSC-SRP and IIE’S Syria Consortium, among others, has largely been on refugees residing outside of the host country, often in camps, who can be identified, screened, and then accepted for placement in the new host country. WUSC, for example, largely recruits students from refugee camps in Africa and the Middle East. It is less clear what coordinating efforts are happening around those who are resettled by host governments or who make their own way into the country as asylum-seekers–the case in all four countries profiled. Major organizations can also play a role in coordinating these efforts, encouraging institutions to identify refugee students, offer scholarships or other financing, and provide support in terms of integrating these students who are already present in the country. Additionally, many efforts currently focus on Syrians – generally because of their large numbers and often because they’re known to have higher levels of education than other refugee groups [105] – but efforts should also focus on other refugee and asylee groups.

Conclusion

IIE’S president Allan Goodman has argued [49] that “the more than 20,000 higher education institutions worldwide should each offer to take in at least one displaced student and rescue one scholar. This would make a dent in preventing a global lost generation, while also saving, in some cases, entire national academies.” The importance of providing refugees from Syria and elsewhere opportunities to continue and complete higher education is clear to many countries. Moreover, wealthy countries’ higher education institutions have the capacity to take in at least one displaced student or scholar. The social and political contexts surrounding refugees and immigration certainly play roles, but institutions in all countries have found creative ways to help refugees, even when not always supported by the general public. Mobilization of the campus community and collaboration with others working on the topic are key.

1. [106] Zanten, A. (1997). Schooling Immigrants in France in the 1990s: Success or Failure of the Republican Model of Integration? Anthropology & Education Quarterly. 28(3). p.351-374.

2. [107] Country Report: France (As of December 31, 2016), Asylum Information Database (http://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/france)

3. [108] Gineste, S. (2016). Labour market integration of asylum seekers and refugees. France. Brussels: European Commission.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).