Jason E. Lane, Director of the Cross-Border Education Research Team, SUNY

Public diplomacy is often referred to as the “first resort of kings.” That is, in the context of international relations, world leaders seek to build relationships and exert influence on foreign nations through the sharing of knowledge and cultural assets. The effort is on fostering goodwill between the people of two nations such that they develop shared interests, often with one nation coming to appreciate and support the systems of the other.

For example, the global dominance of the Hollywood film industry extends U.S. norms and values to moviegoers all over the world; and, thus, leads many viewers to appreciate and support U.S. norms and values. This more passive soft diplomacy is typically considered in contrast to more aggressive hard diplomacy actions such as military intervention and economic sanctions.

Some leaders have long recognized education as a form of soft power, particularly in countries with a well-respected education system. It is more of a long-term investment, with a longer-term payoff than Hollywood. As Senator J. William Fulbright stated [1] about the U.S. flagship international student and scholarly mobility program, “Educational exchange can turn nations into people, contributing as no other form of communication can to the humanizing of international relations.” Studying in another country builds a relationship and appreciation for that country unlike nearly any other experience.

There is a symbiotic relationship between international relations and international education that cannot be ignored. When international affairs are relatively stable, it can be easy to forget this relationship. However, during times of turbulence, the effects can be drastic.

The Impact of Political Turbulence

Take, for example, the relationship between Iran and the United States. In the 1970s, Iran was the leading sender of international students to the U.S. [3] In 1979-80, before the Shah of Iran fell, there were more than 50,000 Iranians studying in the US. After the revolution, that number plummeted, reaching a low of 1,700 students in 1998-1999. This is a 97 percent drop from the one-time top sender of students. International relationships between governments matter to international education.

More recently, the world is experiencing tectonic shifts in the global relationships among nations. Longtime leaders in international education, such as the US and the UK, have gravitated toward more nationalist tendencies, erecting walls, both physical and metaphysical. Other nations in the west have moved in similar directions, though Canada and France have elected leaders more focused on positioning their countries for global engagement. However, while the nations of the west scramble to make sense of this new reality, nations in the rest of the world see this as an opportunity to strengthen their soft power relationships. And, the threat of war on the Korea peninsular looms larger than it has for decades.

Colleges and universities are bracing for the impact.

How Will Higher Ed Fare With the Current Instability?

Recent reports [4] from the Institute for International Education provide a snapshot of how these shifts may impact student mobility trends. The US remains the leading receiver of international students, with a 3.3% increase from 2015-16 to 2016-17. However, the report also indicated that the total new international students coming to the US decreased by 3.4 percent last year and 7 percent this year. This indicates that the pipeline is shrinking, and overall numbers will soon drop.

Cross-border education activities are even more susceptible to the changing international relation dynamics. Instead of recruiting students and scholars to a country for their education, institutions engaged in Cross-Border Higher Education (CBHE) export their education to other nations. Through the establishment of joint degree programs, research centers, outreach offices, and international branch campuses (IBCs), colleges and universities and (indirectly) their sponsoring countries began to more actively exert influence over foreign nations by establishing their educational flag in a foreign country. However, it also entangles them to an even greater degree in the relationship between nations.

International Branch Campuses

The most extreme form of CBHE is the International Branch Campus, which I have been studying as the co-director of for more than 10 years. We define an IBC as “An entity that is owned, at least in part, by a foreign higher education provider; operated in the name of the foreign education provider; and provides an entire academic program, substantially on site, leading to a degree awarded by the foreign education provider.” Essentially, universities are creating embassies of knowledge in foreign countries that provide locals (and those from throughout the region) with access to an educational experience designed by another country as well as the opportunity to earn a degree authorized by that foreign country. These outposts, which mostly provide a curricular experience similar to what is offered at home, both replicate the educational norms and expectations in a foreign environment and award a credential to students that will forever tie them to the home country.

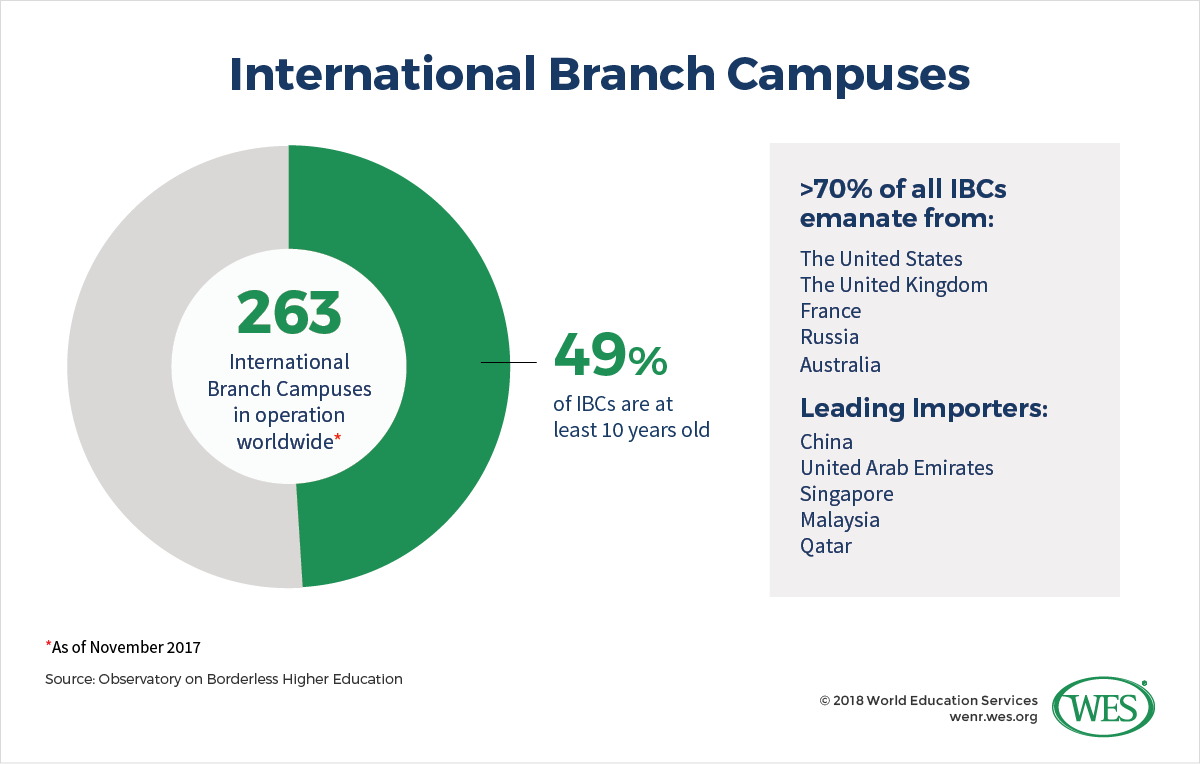

In the grand scheme of tertiary education provision, CBHE is relatively small. Though, our shows that there are 263 IBCs currently in operation worldwide, with more than twenty currently in development. It is a trend that continues to grow.

While a wide range of nations in both the global north and south participate in the exporting and importing of IBCs, more than 70 percent of all IBCs emanate from five countries: 1) The United States, 2) The United Kingdom, 3) France, 4) Russia, and 5) Australia. On the other hand, the leading importers are major players throughout Asia and the Middle East, namely China, the United Arab Emirates, Singapore, Malaysia, and Qatar.

This means that many of the leading world powers, mostly from the west, are exporting their educational systems to the rest. In many ways, this information is likely not surprising to international educators as the patterns are similar to those in student mobility. The leading exporters of CBHE are the leading receivers of international students and the leading importers among the leading senders of students. But, that’s not the story.

While nations of the west seek to erect walls, other countries see this as an opportunity to expand their global engagements.

Opportunities

For example, reports [5] suggest there has been an ambitious and secretive effort of Iranian universities to extend their educational reach, and thereby Iran’s soft power, by establishing IBCs throughout the Arab region. Their reach includes eight other Arab countries including stable nations such as United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Kuwait, as well as nations in transition and rebuilding where their influence may be greater such as Iraq and Syria.

China, a leading importer of IBCs, also has also entered the exporting activities with Chinese institutions setting up in five countries, including Laos, Tokyo, and Malaysia. The Malaysian campus, an extension of the government-owned Xiamen University, is a “good way” for the Chinese government “to export Chinese soft power,” reported Xiong Bingqi from Shanghai’s Jiaotong University [6], and compete with the US, UK, and Australian campuses already offering courses in Malaysia. These efforts also follow Chinese President Xi Jinping’s efforts to advance his nation’s global position “harmoniously” and through building deep relationships with regional nation-states through one-belt, one road [7] strategy.

These efforts demonstrate a growing interest among developing countries to strengthen and leverage their higher education system, potentially moving from education importers to exporters. This furthers growing competition in the international education market.

However, walls can also motivate those behind to break loose, and the increasing tide of nationalism may also provide an opportunity for growth in the IBC sector. As Brexit become more of a reality for UK institutions, they are looking for avenues to continue to gain access to EU research funding and the common student market. One option may be to establish an IBC in continental Europe. There was much speculation, including a widely circulated and later denied a report [8] that Oxford was looking to establish a branch in Paris. Then last summer, reports [9] revealed that King’s College London was exploring an IBC in Germany to circumvent the Brexit wall. The effort is motivated by wanting to mitigate declines in EU Students application to UK universities and preserve research collaborations with EU institutions.

These changing international dynamics do not simply motivate new CBHE entrants; they can also affect existing efforts. Qatar is the fifth largest importer of IBCs with eleven currently in operation. In fact, it has been a sought-after destination for IBCs because of the large government subsidies provided and its stable position in the region – it’s often referred to as the Switzerland of the Middle East. However, that role has recently shattered as the country has dealt with breaks in diplomatic relations [10] from many of its neighbors. While the existing IBCs continue to operate, the current diplomatic tensions leave them in a more precarious situation in terms of attracting students regionally and casts a shadow over other activities in the region.

In Hungary, the government recently tightened its rules around foreign universities in what many have seen as a proxy fight between the country’s nationalist leaders and the liberal philanthropist George Soros [11], who founded Central European University (in Hungary). This change affected McDaniel College, which has had an IBC in Budapest since 1994 and required Maryland officials to broker a deal with the Hungarian government to preserve the IBC.

At the end of 2017, the University of Aberdeen indicated that it might pull out of a relationship to operate a branch campus in South Korea, joining three other IBCs from the US and the Netherlands. The university has already been engaged in the work for more than a year and promoting its presence [12]. However, leaders of the institution have indicated concern that the decline in the oil and gas industry would result in reduced interest in offshore engineering, the campuses intended focus. One cannot help but think that the renewed specter of war on the Korean peninsula may also loom over the decision.

Each of these events, taken alone, makes an interesting tale. Collectively, they illustrate massive shifts happening in the international relations realm and how those shifts can make the fluidity of the cross-border education marketplace even more dynamic. Underlying all of this is also a fundamental reshaping of global power structures. How it will affect international education remains unclear. But, effect it, it will.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).