Eva Egron-Polak, Senior Fellow, former Secretary General, International Association of Universities

The turbulent and challenging political climate around the globe has shocked multiple systems that support civil society as we have come to know it. In the last 18 months, we have seen multiple examples of rising nationalism, parochialism, xenophobia, racism, and more. Consider, among other developments:

- The UK’s referendum on Brexit

- The protectionist walls being built in countries such as Hungary to keep out refugees

- The jailing of university leaders and academics (along with others) by the Turkish government

- The election of Donald Trump in the USA

In this turbulent political climate International Higher Education may be uniquely positioned to address both cultural differences through the direct interchange of ideas and longer-term policy by creating better educated and more thoughtful public citizens.

But are we ready and if so, how can we best take advantage of this positioning?

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals [1] (SDGs) outlined in the 2030 UN Agenda offer an opportunity for the global higher education community to evaluate how universities contribute. Paul Polman, the CEO of Unilever has said that the SDGs act as a moral compass [2] at a time when global leadership is weak.

Why see SDGs as a new policy framework for HE, including for International Education?

- SDGs address all nations – North, South, East and West

- The 17 SDGs are all inter-connected and show that solutions are interdependent; need holistic (multi-disciplinary) approaches

- No SDG can be achieved without involvement – through research, education, and outreach – of higher education institutions

- None can be achieved without international collaboration and commitment

- Current trajectories of development (including in HE) are unsustainable – economically, socially, and politically

- International education and research can serve to raise awareness, be at forefront of search for alternatives, demonstrate centrality of both knowledge and collaboration, gain new impetus by building on other broad agendas

For higher education, the time is ripe. The international higher education community has an opportunity – in fact some would argue an obligation – to step up and demonstrate that building a sustainable future depends on both knowledge creation and collaboration. At the same time, international educators must find ways to close the educational fissures that have contributed to the rise of nationalism, nativism, xenophobia, and racism that are rising in hotspots around the globe.

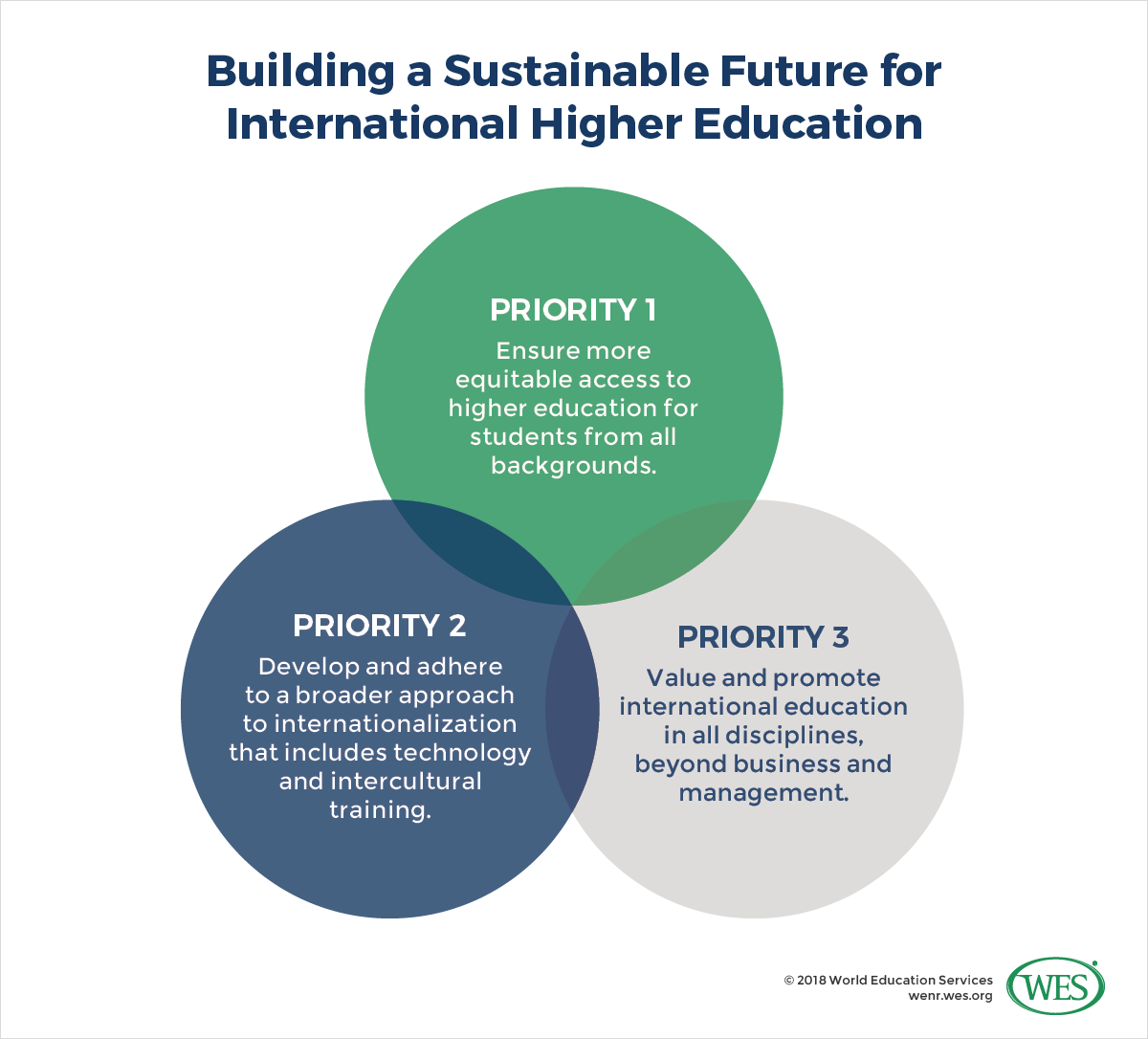

The priorities for higher education, and especially for international education, are relatively clear in this environment:

- Ensure more equitable access to higher education for students from all backgrounds at the national level: The massification of HE remains far from reality in many places around the globe – moreover, much of the expanded access that is available is of uncertain quality, leaving plenty of room for unscrupulous actors to lure unwitting students into signing up for fraudulent courses.

- Develop and adhere to a broader approach to internationalization: The dominant approach to international education today is centered on promoting and facilitating global student mobility. Such an approach is, though positive for those who can participate, highly exclusive. It leaves out many from who cannot afford to travel abroad either for long or even short-term study. One remedy is internationalization of the curriculum at home. This begins by:

- Strengthening the international / intercultural dimension of teacher education

- Expanding the use of technology to connect learners for collaboration on shared projects across borders, without leaving home. (The Collaborative Online International Learning initiative (COIL) provides a great example of how this can be done.)

- Value and promote international education in all disciplines, beyond business and management. More attention must be given to a broader array of disciplines – engineering and medicine for example – to lift the quality of life around the globe. Arts and humanities remain critically important to building cross-cultural empathy and critical thinking skills, encouraging deeper understanding of ethical dilemmas and more enlightened policy-making.

Access for All

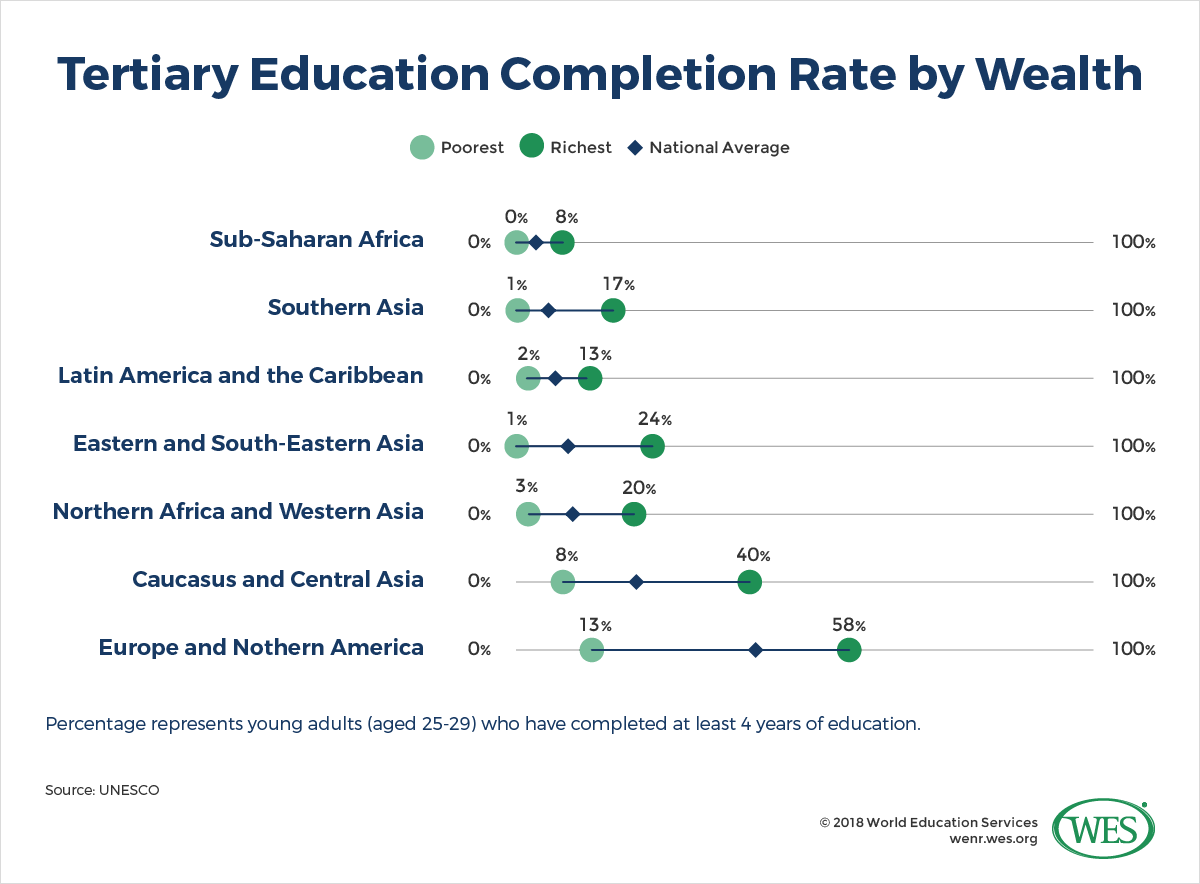

There is a tendency at the U.N, the World Bank and other global institutions to focus on macro trends. “Educational attainment is rising around the world!” Yet such high-level narratives often gloss over the massive gaps and (more) visible inequalities both among and within nations. They focus on the overall number of highly educated people in the world, yet ignore that these gains are primarily concentrated among the economically well-to do. These statements, made with the best of intentions, in fact help to fuel the fires of negative sentiments and discontents, which have recently led to the rise of many of the populist demagogues now in ascendance.

Consider: The political leaders who have led new nativist movements often rose to power by singing from the same songbook, blaming profound societal ills such as unemployment, violence, and more on ‘outsiders,’ whether migrants, religious or ethnic minorities, or refugees.

The real fault lines are more complex. Educational attainment and economic status are two cases in point. In the Brexit vote, for example, pro and con voters were often divided by age, level of education, and economic status. In the most recent U.S. presidential election, education and economic status likewise contributed to tremendous disparities in voters’ likelihood of supporting one candidate versus another.

A Broader Approach to Internationalization

In 2015, two colleagues and I added to Jane Knight’s original and often cited definition of internationalization of higher education (Knight, 2005)1 [5]:

‘Internationalization is the intentional process of integrating an international, intercultural or global dimension into the purpose, functions and delivery of post-secondary education, in order to enhance the quality of education and research for all students and staff, and to make a meaningful contribution to society.’ (De Wit, H. Hunter, F., Howard, L. Egron-Polak, E., 2015)

The reason for the addition of these underlined words and especially the last part is essentially an affirmation that international education serves a wider purpose, one that is linked both to the academic and the social role and responsibilities of higher education. It is also a call to demonstrate how international education contributes to creating graduates who are global citizens and how it can promote social cohesion, create a more peaceful, less divided, and less violent society.

Underlining this social purpose of internationalization is perhaps more important now than ever before, not least because the focus on international higher education is now a matter of national (not just academic) concern in many corners of the world. As ever more governments develop or revise their national internationalization policies, it is important to ensure that such policies are not strictly focused on quantitative indicators related to student mobility or collaboration with the ‘best’ universities in the world

Such national policies in support of internationalization need to be comprehensive and cover all internationally-focused activities. They need to be relevant for all students, including those who cannot pay for an international learning experience through mobility. They must also focus on issues of equity, access and inclusiveness, and ensure that internationalization of the curriculum is among the key goals to be pursued.

Being of relevance to a variety of institutions is also essential – all institutions – rural and urban, small and large, specialized and comprehensive, including those not ranked at the top of national or international rankings – need to find ways and need support to increase their international outlook. And finally, when setting geographic priorities, national internationalization strategies need to encourage collaboration with all nations, not only those that represent a lucrative economic partner or significant market for international recruitment.

Final Thoughts

The benefits of higher education and research are not simply economic or technological. They contribute to our understanding of human relations, create a world that appreciates art and creativity, that recognizes the value of different perspectives and more generally, of the critical mind. The current volatile and unpredictable political situation can lead to questioning the value of higher education and to criticism of internationalization as elitist and irrelevant for many.

Despite some criticisms about scope (too wide) and funding (not enough), the 17 Sustainable Development Goals provide a globally agreed-upon vision for the future. Though only one of the goals is focused directly on education (SDG #4 aims for inclusive and quality education for all and though it is focused on primary and secondary levels, does mentions the tertiary level of education among its targets), the various SDGs require the support of Higher Education institutions and professionals to come to fruition. From the elimination of poverty (SDG #1) and hunger (#2), through the development of sustainable cities (#11), and on to prevailing peace and justice (#16), all of these goals require well-educated and thoughtful public citizens.

It is crucial that higher education institutions remain safe spaces for everyone to question, and engage in critical analysis, to advocate for the value of multiple perspectives and to prepare graduates with the skills to do this throughout life. This is the essential and central goal of international higher education and has rarely been as important as it is now.

Article based on a presentation during WES-CIHE Seminar, June 2017, Eva Egron-Polak, Senior Fellow, former Secretary General, International Association of Universities

1. [6] Jane Knight’s most frequently cited definition is as follows: Internationalization is defined as the process of integrating and international, intercultural and/or global dimension into the goals, functions (teaching/learning, research, services) and modes of delivery of post-secondary ’.

References

Knight, Jane, Internationalization of higher education: new directions, new challenges , IAU Global Survey Report, Paris, 2005, pg. 13

De Wit, Hans, Hunter, Fiona, Howard, Laura and Egron-Polak, Eva, Internationalization of Higher Education, Study commissioned by Policy department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies, Culture and Education, European Parliament, 2015 pp 283

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).