Claire Mengshi Zheng, Team Lead, Credential Analysis, WES

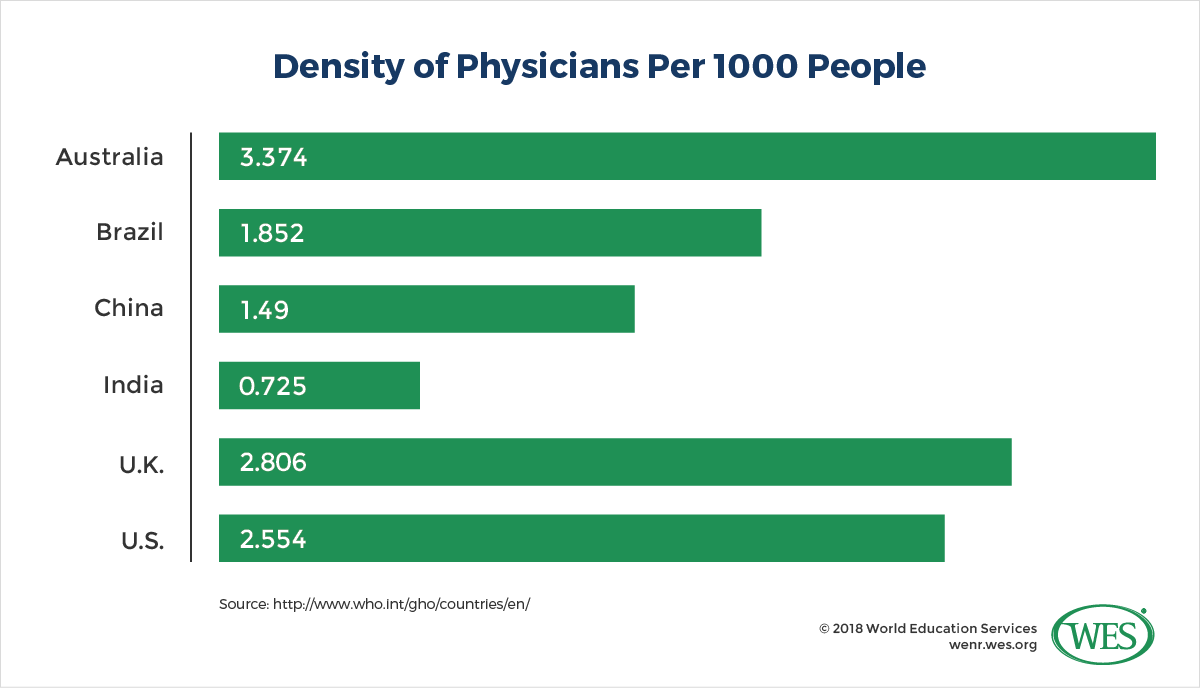

Medical education in India is in a state of disarray. The result is a crisis in access to care. With a shortage of close to a million doctors, an estimated 600 million Indian citizens [2] have little to no ability to obtain treatment from licensed providers.

The Indian government is making an effort to improve the current doctor-patient ratio [3] of 1:1700 to 1:1000 by 2031. But the Medical Council of India [4] (MCI), which oversees all of the country’s Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) programs, faces one fundamental challenge: There are not enough educational institutions to accommodate demand. India currently has 479 institutions that are allowed to teach MBSS programs registered under MCI. These collectively have an annual intake of 61,070 students.

The solution for many students? A medical education in China. For a number of reasons – including cost, quality, proximity, increased capacity, and soft power plays like China’s regional Belt and Road initiative — China has emerged as a top destination.

Medical Education in India: A Snapshot

Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery, abbreviated as MBBS, is a first professional degree in countries that follow the British system of education. It is the equivalent of a doctor of medicine (MD) for countries that follow the American system of education.

India’s private medical education [7] has grown rapidly since the 70s. While public medical schools grew 36 percent between 1970 and 2005, private institutions grew by 1,120 percent during the same period. Although they offer increased capacity, these private schools often carry costly hidden fees, and offer uncertain quality; public schools, by contrast, are funded by the government and tend to carry a higher guarantee of quality.

Cost is a major factor for many Indian students, and despite offering seats, private schools carry a stiff price tag: For example, the yearly tuition for one private 4.5-year MBBS program, SRM medical college in Chennai, recently shot up from USD $15,566 to USD $32,689. In comparison, tuition from public universities stayed around USD $140 – $6,849 for the entire program.

Besides the high cost of Indian private medical universities, the quality of their education is problematic. According to a Reuter’s report [8] from 2015, more than 16 percent of Indian medical schools have been accused of cheating to pass government inspections. More than 50 percent of these medical institutions failed to produce a single peer-reviewed article [9] from 2005-2014.

Although far less expensive, public medical education in India presents challenges as well, chiefly capacity. In 2017, over 1,000,000 applicants [10] compete for 56,000 seats, making the potential overall admission rate only 5 percent. For a more desirable school, the chances are even lower. For example, at Christian Medical School in Vellore, the 2015 admission rate is only 0.25 percent. As a comparison, the 2015 admission rate for Harvard medical school, arguably one of the most competitive MD programs in the US, is 3.7 percent.

Admission to Indian medical institutions is, in general, contingent on passing an entrance exam, the National Eligibility and Entrance Test (NEET). Several top universities also conduct their own admission exams. For example, All India Institute of Medical Science (AIIMS), one of India’s oldest and best-regarded medical universities with seven locations around the country, has its own admissions test. As of 2018, passing the NEET is also mandatory for Indian students seeking to pursue MBBS degrees abroad [11].

China as a destination for medical education

Although historically most international students in China choose to study humanities — Chinese language and literature —international students have, in recent years, begun pursuing a more diverse spread of subjects, including medical programs.

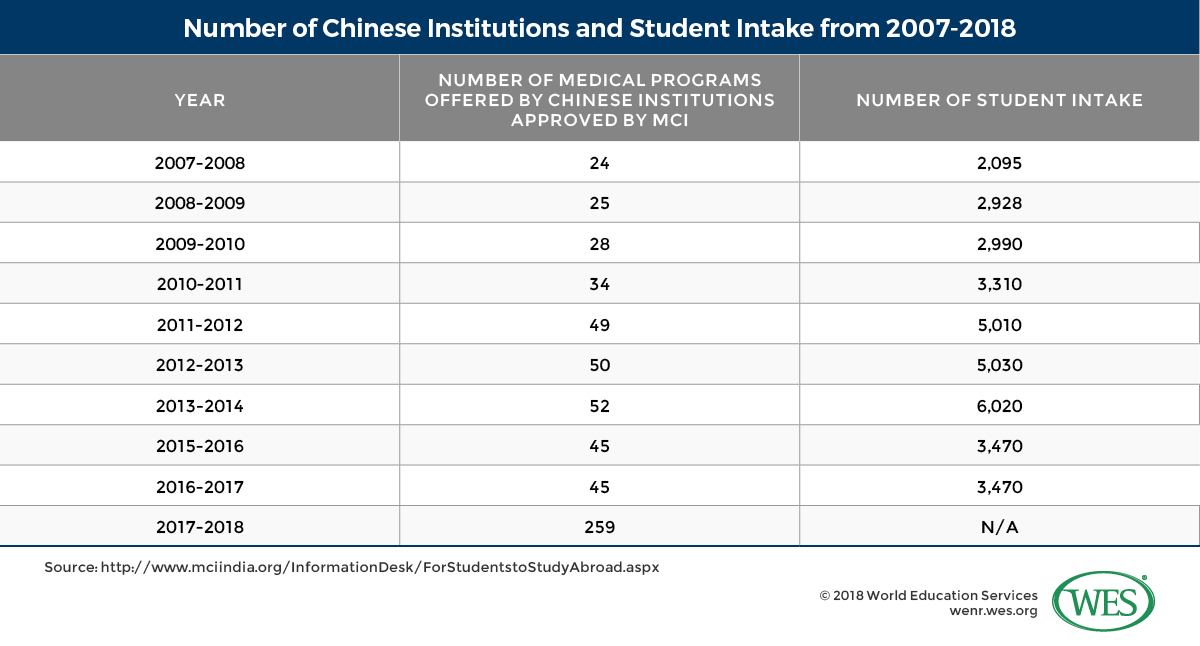

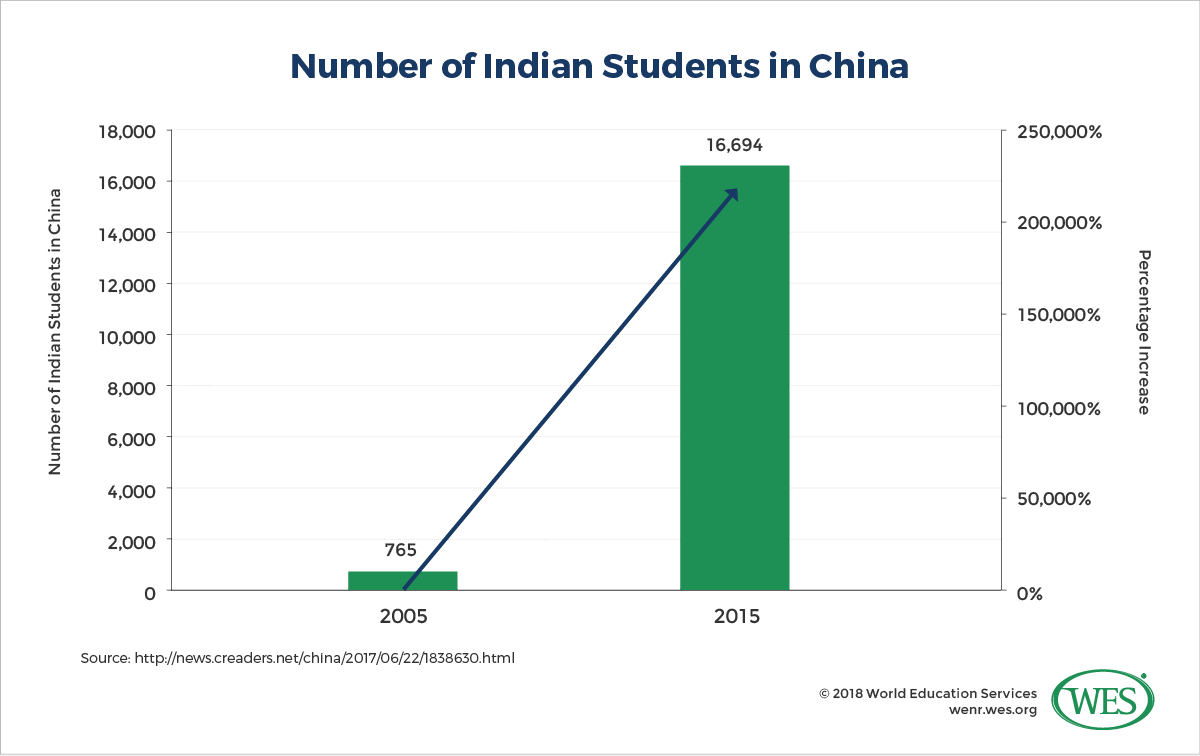

Data from the Medical Council of India reflect this shift, with China emerging as a top destination for outbound Indian students in a relatively short time frame. The number of Indian students in China [12] rose to 16,694 in 2015 as compared to 765 a decade before. 80 percent of those students are enrolled in MBBS programs as compared to international students from other countries in China, among whom over 50 percent choose to enroll in humanities. An estimated 13,300 Indian students are now enrolled in MBBS programs in China.

And the number is expected to grow substantially with the addition of over 200 bilingual Chinese/English MBBS programs in 2017 and 2018. This growth in capacity is exceptional: As of the most recent data available from the World Health Organization, mainland China had 185 accredited degree-granting medical institutions compared to 82 in Russia, 19 in Nepal and 25 in Ukraine (WHO list https://search.wdoms.org/ [13]).

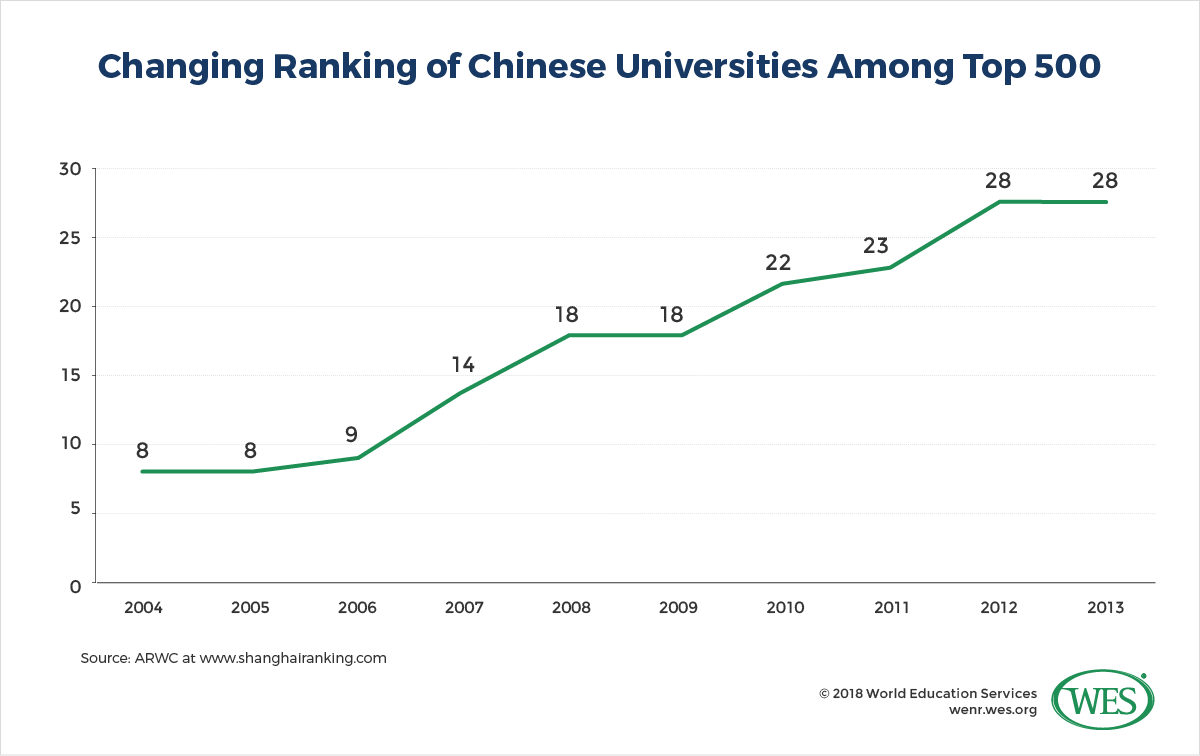

China’s effort to position itself as an international education destination [15] is deliberate and has, to date, been largely successful. As this publication noted last year:

“In 2012, China’s officials announced a goal of becoming an international education hub [16], with a target enrollment of 500,000 international students at all levels of education by 2020. Since then it has attracted hundreds of thousands of students from across Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Americas. By almost any relevant measure, the country has made enormous progress against its goal, and appears poised to make even more.”

One driver of this growth is China’s USD $900 billion pan-Asia Belt and Road Initiative [17]to connect and cooperate economically with various Eurasian countries, including, quite prominently, India. Under the influence of the policy, China’s inbound international student body exceeded 440,000 in 2016, a 35 percent increase from 2012. Another driver is a move toward offering more academic programs in English, he lingua franca of academia and of many Indian students. In fact, there are now roughly 45 medical schools offering courses in English. This has resulted in a large influx of Indian students coming to study in China, 80 percent of who major in medicine.

Whether or not graduates of programs in China – or indeed other foreign countries – can pass India’s Foreign Medical Graduates Examination (FMGE) remains an open question. As a consequence, so does the question of whether Chinese-trained Indian medical students can address the Indian government’s need for doctors. Passing the FMGE is mandatory for an Indian citizen trained in a medical institution outside of India to obtain a license and practice, and recent reports indicate that just 12 to 15 percent of foreign-trained medical students [11] pass the licensure exam.