Elaina Loveland, author and former editor-in-chief of International Educator

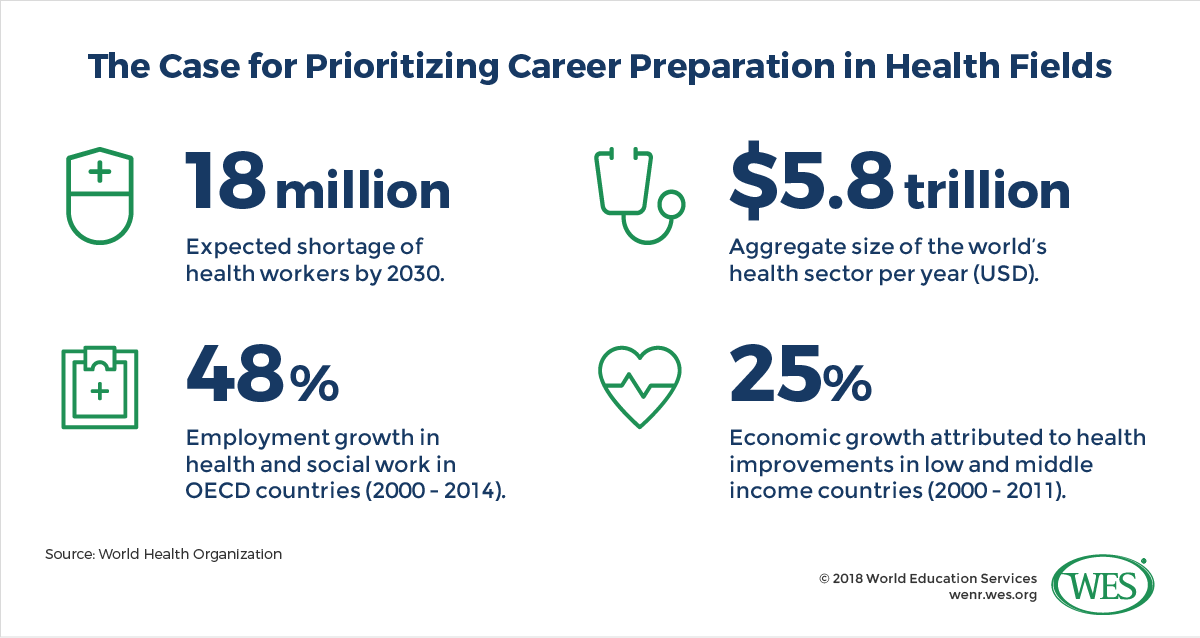

With a looming shortage of health care workers globally—a projected shortfall of 18 million health workers by 2030 according to the World Health Organization—there is no time like the present for universities to prioritize the effort to prepare students for careers in healthcare.1 [1] Because the lack of healthcare workers is expected to be greater in low to lower-middle income countries, it is even more important for universities to assist international students in career preparation in health fields to prepare them for the workforce to combat the crisis the increasingly lack of health professionals around the world.2 [2]

Career preparation is important for any college student, but for international students, specifically those pursuing health-related majors to enter health professions, the journey can be complicated. Upon finishing their degrees, international students may be returning to their countries of origin to enter health fields with their own specific requirements. In other cases, international students may seek to enter the workforce in the United States for Optional Practical Training (OPT) for the short-term before returning home or opt to pursue an advanced degree in a health field in the United States.

International student advisers can assist students on a variety of immigration issues when they consider post-college plans, but when it comes to career preparation, it is often an ideal opportunity to work with other campus offices, such the career center or advisers for health professions, or create a strategic effort to find a way to help international students prepare for careers at home while they are studying in the United States.

“Career offices should be partners hand-holding with international offices,” advises Adria Baker, Associate Vice Provost for International Education and Executive Director of the Office of International Students and Scholars, at Rice University, whose international student population makes up 24 percent of the student body.

“The career offices should not be doing immigration advising, but they have a lot of experience in just being exposed to OPT and CPT and the H1Bs, because they’ve heard it,” says Baker. “They know that the companies that may or may not be interested in sponsoring people or they know if they need the internship time longer than the time that they have on OPT or something, and they know which companies are most likely to hire foreign nationals and which ones are not.”

For international students who are returning home after graduation, reverse culture shock is a common occurrence. International student offices can assist students in preparing to go back home and understand that business etiquette in the United States may be very different than in their home country.

The fact that international students are usually developing their network in the United States rather than in their country of origin can be a hurdle when they go home.

“They’ve created networks here, abroad, so one thing that the international office can do, and the careers office can do, and they can do for themselves, is to continue to build networks when they’re home, even while they’re here,” advises Baker. “There are so many ways that that can happen now with so many global networks, so it allows them to keep their networking when they’re in the home country and keep their networking here.”

Campuses can help international students develop their network even while they are studying in the States, if they make it a priority.

“We always say the first thing to do is look at your own network because everyone has a network,” says Ita Duron‑Hermouet, Director of Admission International Research and Strategy, at MCPHS University, formerly known as the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, which is healthcare-focused university offering a full array of healthcare undergraduate and graduate programs.

Duron‑Hermouet explains that while some international students might not have well-connected family members in health professions in their home countries, everyone has a family doctor or a community pharmacist, for example, and she encourages students to build relationships from their own network.

“Obviously some students have better and not so good networks…that’s when it’s important for the school that they go to, to have network, and for international students, it’s important for that school to have international networking,” she says.

MCPHS creates international networking opportunities for its international students specifically.

“We institutionalize those types of opportunities,” says Duron‑Hermouet. “What I mean by that is, for example, to have a rotation count in a degree, it needs to go through a certain approval process and the preceptor also has to be approved by our accrediting body through a series of processes. It’s a long process. It’s time-consuming, but in the end, when the student goes abroad, practice trains with this preceptor for the required amount of time in an approved institution, then that rotation counts as clinical hours in the American degree. For an institution to invest time in doing that, it’s already a lot of time to get it done in the States, but to invest time in doing that abroad, the institution has to have a true will and strategy in creating those networks for the students.”

For the past five years, MCPHS has invested resources in creating opportunities that hospitals, clinics, and pharmaceutical companies, and some of their international students’ key countries of origin, including rotation sites in Belize, Bolivia, Canada, China, England, Peru, South Africa, and Taiwan.

Baker suggests that institutions should be strategic in establishing university partnerships to establish an infrastructure in which international students can go back to their home countries to do study abroad, internships, service learning, volunteering or clinical heath experiences while they are studying for their U.S. degree.

Rice University has started partnerships with several universities in Latin America to do just this. Baker says that Rice is working with two universities in Costa Rica and several in Brazil and that they are in the process of growing and establishing the relationships as long-term, so that the two-way networks continue to grow.

“What we’re trying to do in the region is trying to set it up so that when the students come here, they have networks here and networks there, so that it continues our relationship with that university, that country, that city, and it helps them to make it a choice of best of both worlds,” says Baker.

When it comes to working with other offices on campus, international student offices can help gain access to resources that other offices may have. For example, career offices have access to alumni who’ve begun working. Connecting students with alumni in their career fields can be a fruitful opportunity for international students when they graduate so they know someone in their country in their career field if they go home or if they are staying in the United States pursuing their career field or advanced degree.

“For the career office to be able to connect students with practicing alum, even recent grads who are not yet ready for the ask, those are very valuable relations for the return or the entry into the job market of recent graduates– and not because they can give them a job, but just simply because they are also able to just talk about the entire process, what happens when you come back,” explains Duron‑Hermouet.

MCPHS has developed such an effort called the Mentor Program in which incoming or new students are paired with students who are in the same program two or three years ahead. When the student graduates, their mentor has graduated, has been in the job market for two or three years. Duron‑Hermouet says that when a student commits to becoming a mentor they are commit to helping out their mentee when they are a student and also after their graduation. The program at MCPHS is for all students—domestic and international. She feels that other institutions could benefit from the idea and target international students to assist them with career preparation and building their network.

“The same type of idea for international students through the career office would be, I think, very helpful,” she says.

Healthcare Credentials Differ by Country—A Challenge to International Students Returning Home

For international students pursuing health professions, going back to their country of origin can be a maze of figuring out how to launch their career with a degree from abroad. Every country has a series of processes to transfer licensures into a country or two to get, acquire licensures for graduates of foreign degrees.

“If you are an international student going back home and you go to the international office and ask, ‘how can I help enhance my career prospects when I’ve been in the U.S. and now I need to go back home and find a job,’ the advice is going to be very specific to that country and very specific to that profession,” says Todd.

Each international student has their own unique set of circumstances (which filed they are pursuing, which country they are from, the job market conditions when they return back to their country, etc.). Most U.S. universities do not typically keep track of the varying requirements for different heath care professions in their students’ countries of origin. However, MCPHS goes a step further to assist international students with figuring out requirements in their home countries than most institutions because it specially prepares students for careers in healthcare fields. Three years ago, MCPHS started a program to assist their international students with navigating the requirements for health professions back in their native country.

According to Duron‑Hermouet, the program lays out the entire process very clearly.

“What we do is we take the student’s profile and ask questions like, ‘Where are they starting at? And then where do they need to be in order to get through that process?’ And sometimes it can be language, sometimes it can be clinical hours, sometimes it can be degree,” she explains. “The students start at different points. Once we’ve got everyone up to all the requirements, the level that they need to be at in order to pass the different stages of the process, then we guide them through the stages.”

Staying in the United States to Pursue an Advanced Health-Degree Program

Campus administrators should know that for international students who want to remain in the United States to pursue an advanced degree in a health field, it’s more that grades that matter.

“What separates the students from each other isn’t really in the test scores, it’s in the letters of recommendation, the personal statements, which is their story, and the interview,” explains Tricia Todd, Interim Director with the Pre-Health Student Resource Center at the University of Minnesota and an instructor in the Public Health Practice major in the School of Public Health.

“Medicine, as well as a lot of other health professions, are moving towards competency-based education,” says Todd. “They’re looking at some very specific competencies—many of those are character competencies. They’re things that suggest that you’ve got resilience, you’ve got reliability, you’ve got good communication skills, you know how to work in a team.”

Todd says that while many of those skills aren’t learned in the classroom and the message is the same for domestic students, international students may have a more difficult time attaining the competency-based skills that advanced degrees in health professions seek.

“You’ve got to go beyond the classroom to get these. The challenge an international student might face is the cultural nuances and the language,” she says.

International offices can help international students understand that acquiring skills outside the classroom can be just as important as their grades, in some cases. Activities like volunteering and internships (if immigration and/or institutional guidelines permit these), or participating in campus activities can be useful for career preparation.

Early Planning Is Key

It’s never too early for universities to remind international students to think about their career aspirations. According to Duron‑Hermouet, international students especially need to be preparing their entry into the job market from their first year on campus.

“In their first year, they’re going to be going to volunteer or going to a seminar and the people they meet at the seminar or during their volunteer work that’s going to help them get the internship,” she says. “Then depending on where they did their internship, that’s going to open the door, maybe, to certain rotations. Then where they do their rotation could open the door to where they’re going to be doing their residency and it’s moving backwards, where you can go to have references, where you can talk about those experiences and everything you’ve learned from those experiences that you build up the moment where you actually enter the job market.”

Whether an international student will return home, decide to participate in an OPT experience and extend their stay in the United States, or pursue an advanced U.S. degree, international offices can be a champion for them by helping them build their network from afar, working with the career development office on campus, and making strategic choices about campus partnerships to help them in their future careers.

1. [4] World Health Organization. Working for health and growth: investing in the health workforce—report of the High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth. 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250047/1/9789241511308-eng. pdf.

2. [5] Ibid

Elaina Loveland [6] is a freelance writer and editor based in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. She previously edited International Educator magazine, the Journal of College Admission, and GAMA International Journal.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).