Dragana Borenovic Dilas, Credential Examiner at WES, Jean Cui, Research Associate at WES, and Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

This country profile describes current trends in education and student mobility in Nepal and provides an overview of the Nepali education system. It replaces an earlier version by Nick Clark, published in 2013.

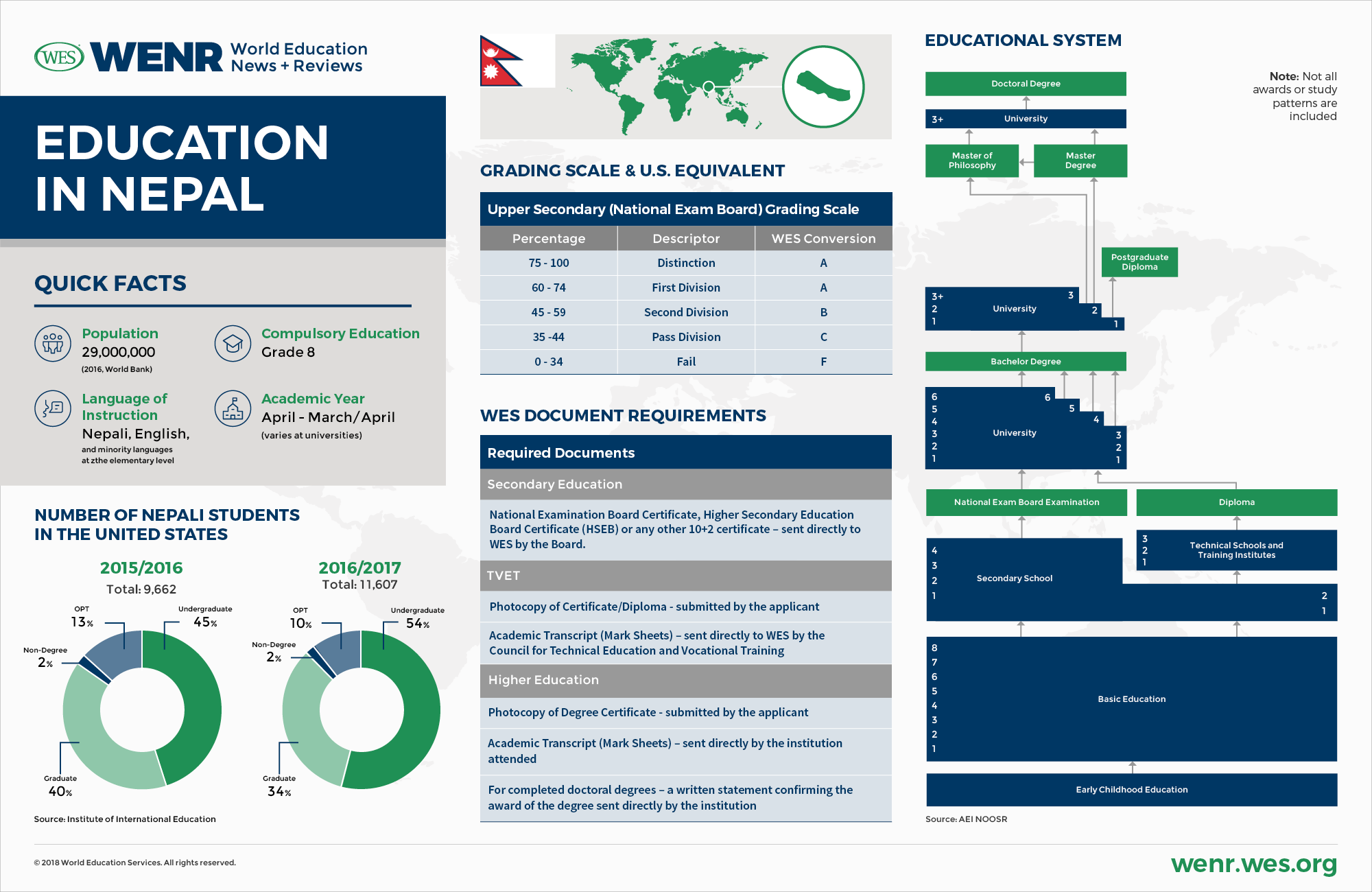

Nepal is an increasingly important sending country for international students. In the United States, the number of Nepali students increased by more than 20 percent in 2016/17 [2], the highest growth rate among the top 25 sending countries [3] by far. This makes Nepal one of the countries bucking the “Trump effect,” which led to an overall decline in new international student enrollments [4] in 2016/17.

Limited educational and employment opportunities in Nepal are among the factors driving the outflow of Nepali students. Political instability—there have been nine different governments between 2008 and 2016 alone—and devastating earthquakes in 2015 have worsened social conditions in the country. However, the government seeks to improve the education system with reforms, such as the extension of compulsory basic education to eight years of schooling.

Introduction

Nepal is a small country of 29 million people situated on top of the world. Wedged between the mega-countries of China and India, Nepal is home to eight out of the ten highest mountains in the world, including Mount Everest. The mountainous terrain of the land-locked country presents tremendous challenges for socioeconomic development and makes it difficult and costly to expand Nepal’s infrastructure. In 2015, Nepal remained one of the least developed countries in Asia and ranked 144th out of 188 countries in the UN Human Development Index. [5] According to the Asian Development Bank, about 25 percent [6] of the population existed on less than USD $1 per day in 2010/11.

Further impeding socioeconomic development is Nepal’s susceptibility to earthquakes. In 2015, the country was struck by two consecutive earthquakes, one of them the strongest quake in more than 80 years. This catastrophic event killed more than 8,600 people and destroyed or severely damaged large parts of the country’s infrastructure, including almost 500,000 houses [7] and more than 9,300 schools [8]. Hundreds of thousands of families were displaced [9], and more than 700,000 people [7] were pushed into poverty as a result of the catastrophe. The impact on the education system was disastrous, and recovery is progressing slowly [10]. One year after the quake, more than 70 percent of affected people in the hardest-hit areas still lived in temporary shelters [11]. Many children had to be instructed in makeshift tents, resulting in a noticeable increase in dropout and grade repetition rates [12]. As of January 2018, only 88,112 private homes and 2,891 schools had been rebuilt [13].

One reason for the slow progress in recovery is the high degree of political instability and fragmentation in Nepal. Nepali society is still largely agricultural [14] and highly stratified, with upper caste Hindu elites dominating a multicultural society that includes 125 ethnic groups/castes speaking 123 languages (according to the latest 2011 census [15]). Only 44.6 percent [15] of the population speaks Nepali, the national language of Nepal, as their first language.

Although Hindus constitute a majority of 81.3 percent [15] of the population, there are deep caste divisions within the Hindu populace. The marginalization and deprivation of lower castes, most notably the Dalits (“untouchables”) and other groups like Buddhists and Muslims (10 and 4 percent of the population, respectively), has been a source of conflict for decades. Lower castes and other marginalized groups have less access to basic services and education, and fewer opportunities for social advancement [16]. Similarly, Nepal is characterized by strong regional disparities and urban-rural divides between more developed regions like the Kathmandu Valley and less developed rural regions.

In recent years, Nepal has witnessed a violent 10-year insurgency of Maoist rebels (from 1996 to 2006) and the temporary re-establishment of absolute monarchy in a royal coup d’etat in 2001. A 2006 peace agreement paved the way for the eventual re-democratization of the political system, culminating in the first parliamentary elections in Nepal in 17 years in 2017 [17].

It remains to be seen, however, if parliamentary elections and the adoption of a federal and more inclusive constitution can help stem political instability and turmoil in Nepal. The political process remains characterized by political infighting and corruption [18]. Both the adoption of the new constitution in 2015 [19] and the run-up to parliamentary elections [20] in 2017 were accompanied by violent protests. But while political dysfunction has slowed progress on many fronts thus far, most experts agree that federalism is the optimal form of government for an ethnically and religiously diverse and fractured country like Nepal. The evolution of the political system is also seen as instrumental in pushing education reforms [21].

It is also noteworthy that the Nepali economy is growing, political turmoil and natural catastrophes notwithstanding. While the 2015 earthquake hampered economic output and was followed by the weakest economic growth in 14 years [22] in 2016, Nepal’s economy rebounded quickly. According to the Asian Development Bank [23], Nepal’s GDP grew by 6.9 percent in the 2017 fiscal year and is expected to grow by a further 4.7 percent in the current 2018 fiscal year. While large-scale poverty remains a major problem, poverty rates are declining, as reflected by the fact that the country’s middle class grew from 7 percent in 1995 to 22 percent in 2011 [16], per World Bank definitions.

International Student Mobility

International student mobility in Nepal is predominantly outbound. While there is little public data available on international student enrollments in Nepal, inbound mobility to Nepal is minor by international standards. The lack of top-quality universities, scholarships, and post-graduate work opportunities in Nepal’s lesser economy limits the attractiveness of the country as a destination for international students. While neighboring countries are often a source of student inflows, this is not the case in Nepal either—neither India nor China send high numbers of students. In 2011, the only year for which the UNESCO Institute of Statistics [24] (UIS) provides data, there were 107 international degree students in Nepal. The Institute of International Education (IIE) reports that 370 U.S. students were studying in Nepal in 2016/17 (Open Doors [25]).

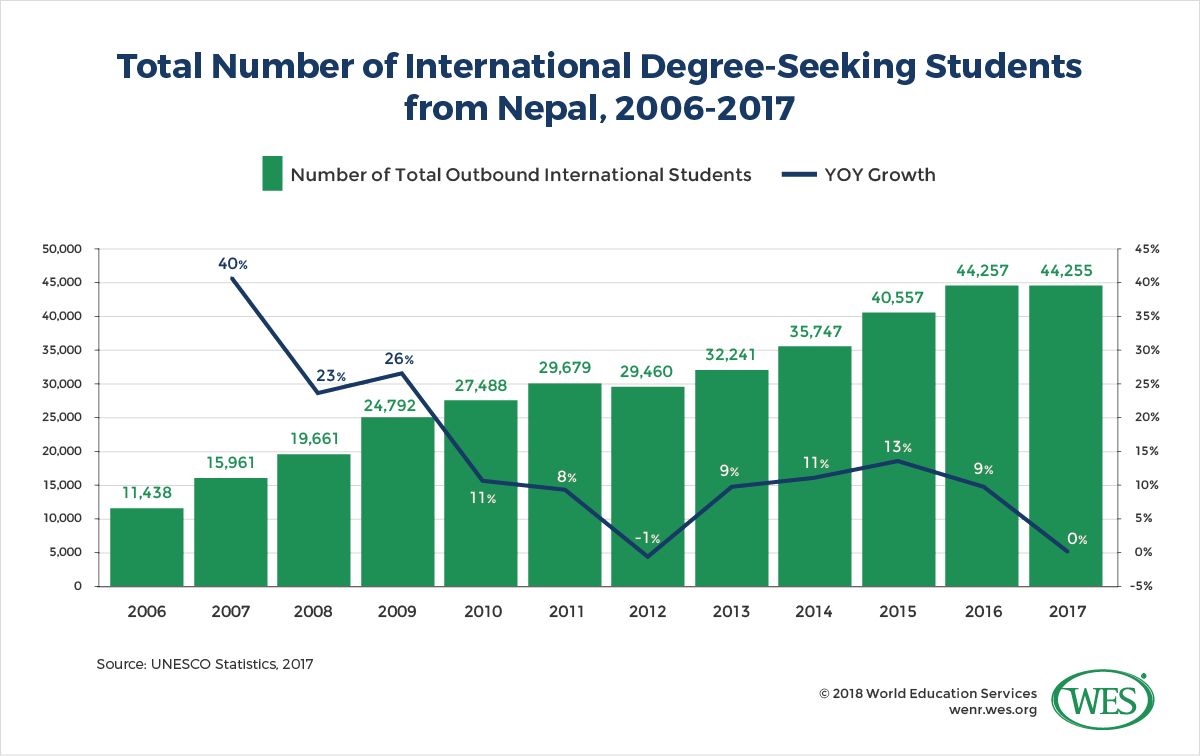

Outbound Mobility

Outbound mobility, on the other hand, is booming: between 2000 and 2016, the number of Nepali students enrolled in degree programs abroad soared by 835 percent and stood at 44,255 students in 2017 (UIS). And while that number is smaller than the number of international students from major Asian sending countries like China, India or Vietnam, it should be noted that the outbound mobility ratio in Nepal—i.e., the number of international students among all students—is much higher in Nepal than in these big sending countries. Nepal’s outbound mobility ratio almost doubled over the past decade and is now more than twelve times as high as in neighboring India. In 2016, Nepal’s mobility ratio was 12.3 percent, compared to 0.9 percent, 1.9 percent and 3 percent in India, China and Vietnam, respectively (UIS).

The increasing mobility of Nepali students is not completely surprising. Nepal is very much a country on the move, and the recent surge in student mobility coincides with drastic increases in labor migration from Nepal over the past decade. As much as 28 percent [27] of the Nepali workforce (4 million out of 14 million workers) are currently working overseas. Like these workers, many international students are leaving the country due to limited higher education options in Nepal, high unemployment among youths, and the prospect of better education and employment opportunities abroad [28].

It is likely that outbound student mobility from Nepal is going to increase further in the near term. The country’s population is becoming more affluent and is growing—the government expects the population to increase from 29 million to 33.6 million by 2031 [29]. Demographically, Nepal is currently experiencing a “youth bulge phase [27]”: World Bank data [30] shows that the share of university-age youths among the Nepali population (ages 20 to 29) stood at about 36 percent in 2016 and analysts expect Nepal to be among the countries with the fastest growing population of 18 to 22-year-olds in the coming years [31].

This growth of the youth population will increase demand for education and burden the education system. As ICEF Monitor has noted [31], the situation in Nepal mirrors mobility patterns in other South Asian countries, in which rapidly growing demand for education outstrips supply. Mobility is expected to grow particularly at the graduate level—a sector that is underdeveloped in Nepal with less than one percent [31] of university campuses offering Ph.D. programs, for instance. The British Council noted in a recent study [32] that Nepal will be one of the top ten countries with the strongest growth rates in outbound mobility over the next decade along with countries like China, India, Pakistan, and Nigeria. The Council anticipates that the number of international Nepali students will increase by another 20,000 students [33] by 2027.

Destination Countries

The most popular destination countries of Nepali students enrolled in degree programs abroad include Australia, India, the U.S., Japan, and the United Kingdom (UIS). Over the past years, the number of Nepali students in Australia has surged, making Nepal now the third largest sending country after China and India. As of November 2017, fully 5 percent of the 621,192 international students in Australia came from Nepal, according to data [34] released by the Australian Government Department of Education and Training.1 [35] Factors like a high number of top-quality universities, simplified visa regulations [36], and relatively low costs of study when compared to countries like the U.S. and the U.K. make it all but likely that Australia will continue to be a leading destination for Nepalese students in the future.

In the U.S., the number of students from Nepal has in the past two years rapidly increased as well. While enrollments from other Asian countries like South Korea or Japan declined in 2016/17, enrollments from Nepal increased by more than 20 percent—the highest growth rate among the top 25 sending countries (IIE, Open Doors [3]). There have been some downward fluctuations over the past decade, but the number of Nepali students in the country is now almost twice as high as in 2005/06 and Nepal is currently the 13th leading country of origin with 11,607 students [3].

Nepali students prefer STEM majors by a disproportionally large margin, with math/computer science, physical/life sciences, and engineering being the most popular disciplines [37]. This attraction towards STEM majors is likely owed to the fact that STEM education is still largely underdeveloped in Nepal [38] and graduates in technical fields have better employment prospects [28] when returning home. Most Nepalis in the U.S. are enrolled at the undergraduate level (54 percent), where the recent growth in enrollments has been strongest (34.4 percent were enrolled in graduate programs and the rest in other programs in 2016/17).

Looking forward, Nepal is certainly an attractive and upcoming recruitment market for U.S. universities, even though Nepali students are constrained by limited financial resources and would therefore greatly benefit from targeted scholarship programs. Many Nepali students in states like New York and California reportedly work long hours in odd jobs to finance their studies [39].

In Brief: The Education System of Nepal

The contemporary Nepali education system did not evolve before 1951 when the country began to transition from an absolute monarchy to a more representative political system, despite various political setbacks over the following decades. At the beginning of the 1950s, education in Nepal was still an exclusive privilege of wealthy elites—the literacy rate stood at only 5 percent [40], and there were only a few hundred schools with about 10,000 students [40] (less than 1 percent [6] of the population). The country did not have any universities at the time. Women were discriminated against and discouraged from attending school in Nepal’s conservative Hindu-dominated society.

Since then, access to education has expanded greatly. Reforms such as the 1971 National Education System Plan [41] have created a much more modern and egalitarian education system with compulsory public basic education. There are now 35,222 [42] elementary and secondary schools and 10 universities with more than 1,400 colleges [43] and campuses throughout Nepal (2016). Expanding educational opportunities is a priority of the government: its current 2016 School Sector Development Plan [8] seeks to graduate Nepal “from the status of least developed country by 2022 through strengthening … access and quality of education.”

Current Education Indicators – Some Facts and Figures

Much progress has been made. Most Nepali youths today have much better educational opportunities than their parents. Net enrollment rates in elementary education, for instance, increased from 66.3 percent in 1999 to 97 percent in 2016 (World Bank [44]). Net enrollment rates in secondary education grew from 44.9 percent in 2007 to 60.4 percent in 2015 before dropping down again to 54.4 percent in 2016, presumably due to the 2015 earthquake. The most dramatic improvements, however, have been made in increasing female participation in education. Between 1973 and 2016, the gender parity index for school enrollments in elementary and secondary education jumped from 0.17 to 1.08, meaning that female entry rates in education improved from being marginal at best to females now enrolling at slightly higher rates than males (World Bank [45]).

At the same time, the school system remains plagued by high dropout rates with girls still being more likely to leave school earlier than boys. While retention rates have increased strongly over the past decades, only 76.8 percent of pupils in cohorts that enroll in elementary education survived until the last grade of elementary education in 2015 (UNESCO [24]). Most children who drop out of school come from impoverished households or live at great distances from school. Children from poor families are often forced to quit school because they have to help their families with farming work or have to walk long distances to attend classes [46]. Also, the education of girls is still not seen as a priority in some rural households and child marriage is still a relatively common practice even in the cities. According to Human Rights Watch, 37 “percent of girls in Nepal marry before age 18, and 10 percent are married by age 15 [47].”

Completion rates in Nepal’s school system generally decrease by level of education: according to the most recent UNESCO statistics [24], the completion rate in lower-secondary education stands at 69.7 percent (2016) and drops sharply to 24.5 percent at the upper-secondary level (2014). Lower casts and other underprivileged groups also remain underrepresented in the education system and affected by higher dropout rates. In the Terai region at the border with India, for example, only 23.1 percent [8] of Dalits were literate in 2016, compared to 80 percent among the higher casts of Brahmans and Chhetris.

In the country as a whole, the adult literacy rate remains strikingly low and stood at only 60 percent [48] in 2011, far below the global average of 84.6 percent (the youth literacy rate was much higher at 84.8 percent, but still below the global average of 89.6 percent in the same year). Merely 56 percent of the Nepali population over the age of 25 had attained more than lower secondary education in 2011. [49] This is reflected in a very low tertiary gross enrollment ratio of 14.9 percent in 2015 [50]—a number that is less than half the global average and 12 percentage points below the enrollment rate in neighboring India.

Administration of the Education System

Nepal’s system of governance is currently in transition. Since the adoption of the 2015 constitution, Nepal is delineated into seven different states, with political powers, including the administration of education, expected to shift increasingly to states and local governments. However, the implementation of the new federal system is a conflict-ridden [51] and slow-moving [52] process fraught with setbacks and delays. During the current transition period, not all local governments are fully functional yet [53], and much of Nepal’s education system continues to be administered under the previous system, in which the Ministry of Education oversaw five Regional Educational Directorates, under which there were various District Education Offices and Resource Centers implementing policies at the local level [54].

The Federal Ministry of Education (MOE) is responsible for developing overall education policies and directives for the country. While it is unclear how exactly the role of the MOE will evolve in the federal system, the responsibilities of the MOE continue to be far-reaching and include curriculum and textbook development, the training and recruitment of teachers, and conceptualizing and administering Nepal’s national school leaving examinations through its National Education Board [55].2 [56]

Universities are overseen by the University Grants Commission (UGC)—a regulatory body under the auspices of the MOE. The UGC disburses government grants to universities, advises the government on the establishment of new universities, sets quality standards, and formulates policies intended to advance the quality of higher education [57].

Vocational education and training falls under the auspices of the Council for Technical Education and Vocational Training (CTEVT)—an autonomous body under the MOE. CTEVT oversees and quality-controls technical and vocational schools. It sets curricula, testing requirements, and skills standards in various occupations [58].

Elementary Education

Until 2016, elementary education in Nepal lasted for five years—from grade 1 to grade 5 (ages five to nine). However, a new education bill passed in 2016 [59] extended the elementary education cycle and established a new system of compulsory basic education that is meant to be accessible to every child in Nepal free of charge at public schools. Compulsory basic education now lasts eight years (grades 1 to 8). In addition, children have the option to enroll in public ‘early childhood development centers’ or private kindergartens before entering elementary school at the age of five. Access to early childhood education, however, remains problematic in many parts of the country and participation rates are low [60].

The basic school curriculum is set in a national curriculum framework [61], which is currently under review. It includes standard subjects like language education (Nepali and mother tongues), English, mathematics, sciences, social sciences, physical education, and some elective subjects in higher grades. Promotion is based on term-end and year-end school examinations, while grade 8 concludes with a district-wide final examination. The academic year runs from April to March/April and is structured around the Nepali New Year in April. Nepal uses a calendar based on the Bikram Sambat system that is different from the Roman calendar (the year 2018 is the year 2074 in Nepal).

The language of instruction in public schools is predominantly Nepali, while private schools often use English. Nepal’s current “school sector development plan [62]” seeks to strengthen educational outcomes among marginalized groups and stipulates that minority languages should be used as the primary means of instruction in grades 1 to 3 in areas where these languages are the lingua franca. This change is intended to make it easier for children who do not speak Nepali at home to comprehend the school curriculum. However, a lack of teachers and teaching materials in these languages means that the reforms are progressing only slowly.

Secondary Education

Prior to the recent reforms, the secondary school system was divided into two years of lower secondary education (grades 9 and 10) and two years of higher secondary education (grades 11 and 12), with both segments concluding with separate national examinations. Under the current system, both stages have been combined into a unified 4-year secondary education cycle. The old national School Leaving Certificate (SLC) Examination held at the end of grade 10 will now be held at the regional level [63] and has been renamed [64] into “Secondary Education Examination” (SEE). Nationally, there will be only one final national school leaving exam at the end of grade 12. These changes have been in the making for quite some time, but were eventually signed into law in 2016 and are currently being implemented.

Admission into secondary education is based on passing the final district-level examination at the end of grade 8. Students can choose between two secondary tracks: general and vocational-technical. The general curriculum [65] includes compulsory subjects like Nepali, English, science, mathematics, and social sciences, a vocationally oriented subject, and one elective subject (local language, foreign language, or another vocational subject). The vocational/technical stream, on the other hand, has a more applied focus in subject areas like agriculture, medicine, forestry or engineering. This stream, however, is still in a pilot phase [66] and is presently only offered at a limited number of schools. According to the 2016 education legislation, students in the vocational track will now also be required to complete an additional one-year practical course after grade 12 to better prepare graduates for employment [67].

Assessment and promotion are based on examinations throughout the year and one final year-end exam. In order to progress to higher secondary education, students under the old system first had to pass the demanding national SLC exams at the end of grade ten, commonly referred to as the “iron gate” due to the very low pass rates in the exam (in 2015, less than 48 percent [68] of candidates passed). While the system is currently in flux, it appears that the (possibly less demanding) region-level SEE exams at the end of grade ten will still be required for promotion to grade 11 going forward.

Secondary education concludes with an external national examination conducted under the auspices of the National Examinations Board (previously the Higher Secondary Education Board). The final credential awarded upon the passing of the examination is presently called the National Examination Board Examination Certificate (previously the Higher Secondary Education Board Examination Certificate). Alternatively, students can, after grade ten, enroll in university-preparatory programs offered by universities that lead to a “Proficiency Certificate,” a credential that gives access to tertiary education (a similar type of credential may be called “Intermediate Certificate” at some institutions). Proficiency Certificate programs are two or three years in length, usually combine general education with specialization subjects, and may require passing an entrance examination for admission. These programs are being phased out, but are still offered at some institutions.

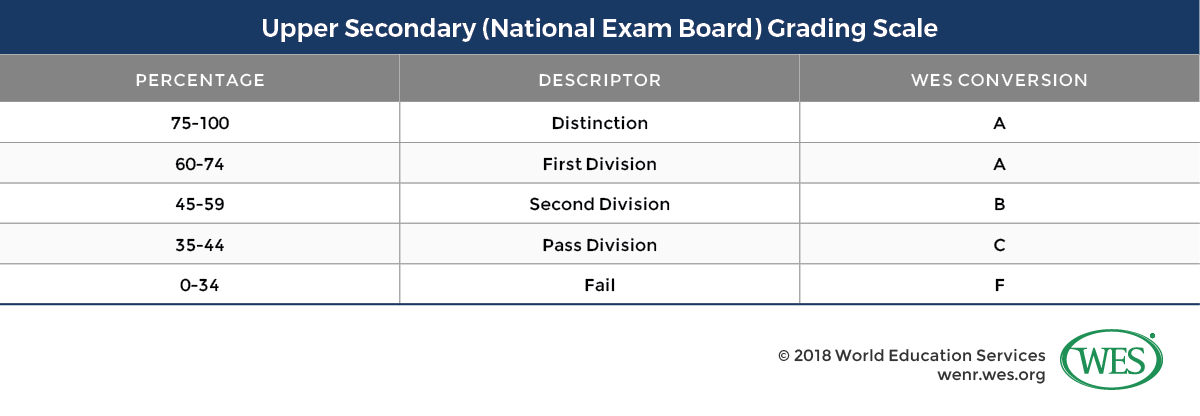

The grading scale used in the National Examination Board examination is currently slated to be changed [69] to a letter grade system with nine grades (A+, A, B+, B, C+, C, D, E and N). As of 2017, however, the following percentage-based grading system was still in use.

Secondary education in Nepal predominantly takes place in so-called community schools, which are public schools that are either fully government-funded or at least government-subsidized. Enrollments in private schools, called “institutional schools,” are growing but still relatively small. There were 29,207 community schools [42] and 6,015 private secondary schools in Nepal in 2016. According to the UIS [24], enrollments in private schools accounted for 17.2 percent of all enrollments at the lower-secondary level in 2017 (up from 13.6 percent in 2011). Tuition-funded private schools often provide better quality education. The pass rates of private school students in the SLC examinations, for instance, are much higher and stood at almost 90 percent in 2015 [71] , compared to 34 percent at public schools.

Private education is out of reach for most Nepalis. But even study at public schools can be expensive for low-income households—a fact that negatively affects participation rates in education. Secondary education in Nepal is neither compulsory nor entirely free. The current constitution [72] guarantees every citizen the right to “free education up to the secondary level from the state,” after the previous interim constitution already guaranteed this right to girls, ethnic minorities, and children from impoverished families. In reality, however, many parents are still required to pay school fees and cover expenses for other items, such as books, teaching materials, or uniforms. More than half of all expenditures on secondary education in Nepal were still borne by private households in 2015 [73].

In addition to community schools and institutional schools, there are a number of religious schools (madarasas, ashrams, etc.) that teach the national school curriculum (in addition to religious studies). There are also a number of international schools in Nepal that teach foreign curricula. The British School in Kathmandu [74], for example, follows the British curriculum and prepares students to sit for British qualifications, such as the International Certificate of General Secondary Education.

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

There are a variety of formal and informal TVET programs on offer in Nepal’s education system. TVET is critical for human capital development in Nepal, especially in light of the country’s looming “youth unemployment time bomb [75].” Youth unemployment is rising quickly, and many Nepali youths enter the labor market without marketable skills [6] (or out-migrate from Nepal). The government therefore actively promotes the expansion of the TVET sector. CTEVT, the regulatory authority for TVET, now directly operates 31 technical schools and polytechnics [76] and has accredited hundreds of affiliated private TVET providers [77]. Programs are offered in a multitude of fields, ranging from medical lab technology [78] to agriculture, nursing, culinary arts, automotive technology, hotel management or computer technology. The most common types of programs available are:

Short-Term Certificate Programs

Trade schools, technical schools, and training centers offer short-term TVET programs that usually have no specific admission requirements and last from one week to 10 months, depending on the program. Graduates earn a certificate of completion, but may also opt to obtain a National Skill Test Certificate [79], which is awarded after passing a practical skills test administered by the National Skill Testing Board (under the auspices of CTEVT). The National Skill Test Certificate certifies occupational proficiency at four different levels.

Formal Secondary-Level Programs

Formal programs at the secondary level usually require at least completion of grade 10 (respectively the SLC) for admission, but may also entail additional entrance examinations. Programs are between 15 and 29 months in length, concluding with a final examination and leading to a Technical School Leaving Certificate (TSLC) awarded by CTEVT.

Diploma and Technician Certificate Programs

Diplomas and Technician Certificate programs are more advanced and usually require three years of full-time study to complete. They typically have a greater focus on theoretical classroom instruction and go beyond the TSLC in scope and intent. Admission is based on completion of grade ten (SLC) or the TSLC and often also requires the passing of an entrance examination. Most programs are taught at technical colleges and polytechnics, but some universities also offer diploma and certificate programs. Graduates with these types of qualifications may, under certain conditions, be admitted into bachelor’s programs at universities [6]. A three-year Diploma in Engineering, for instance, provides a common pathway into tertiary engineering programs.

Tertiary Education

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs)

Higher education in Nepal did not evolve before the 20th century. The first higher education institution, Trichandra College, was established in 1918 but was reserved for privileged members of the ruling Rana family [28]. The first university that was open to the wider public, Tribhuvan University, was not founded before 1959 and remained the only university in Nepal until 1986 [80]. Today, Tribhuvan University is still the largest university in Nepal and enrolls about 79 percent [80] of all Nepali students (2015/16).

The number of HEIs in Nepal has grown considerably since the early days. That is not to say that there are now a large number of universities proper in Nepal. One particular feature of the Nepalese education system is that there are relatively few universities, but a very large number of campuses and affiliated colleges under the umbrella of these universities. As of recently, there were only nine universities and four university-level medical academies (deemed universities). The universities were: Tribhuvan University, Nepal Sanskrit University (an institution focused on Sanskrit education established in 1986), Kathmandu University (founded in 1991), Purbanchal University (1994), Pokhara University (1997), Lumbini Buddha University (2005), Agriculture and Forestry University (2010), Mid Western University (2010), and Far Western University (2010).

In 2015, the MOE proposed to establish three new universities [81]—the Open University of Nepal and two regional universities in the country’s South. The Open University started to operate in 2016, and the creation of Rajarshi Janak University was approved by parliament in 2017 [82], so that Nepal will soon have 11 universities (the fate of the third proposed university, Nepalgunj University, remains in doubt [82]). The new universities are expected to increase access to higher education in the provinces. The Open University is designed to reach student populations in remote regions via open and distance learning programs. It just announced that it will offer distance education programs up to the master’s level [83].

All universities in Nepal are public institutions, even though institutions like Kathmandu University, Purbanchal University, and Pokhara University have a high degree of autonomy akin to the freedom usually only afforded to private institutions [28]. These three universities are also almost exclusively funded by tuition fees. Whereas almost 90 percent of revenues at Tribhuvan University, for instance, come from government funds, Kathmandu University, by contrast, draws 100 percent [28] of its standard operating expenditures from student fees. The distinction between public and private institutions can, thus, be blurry in some cases.

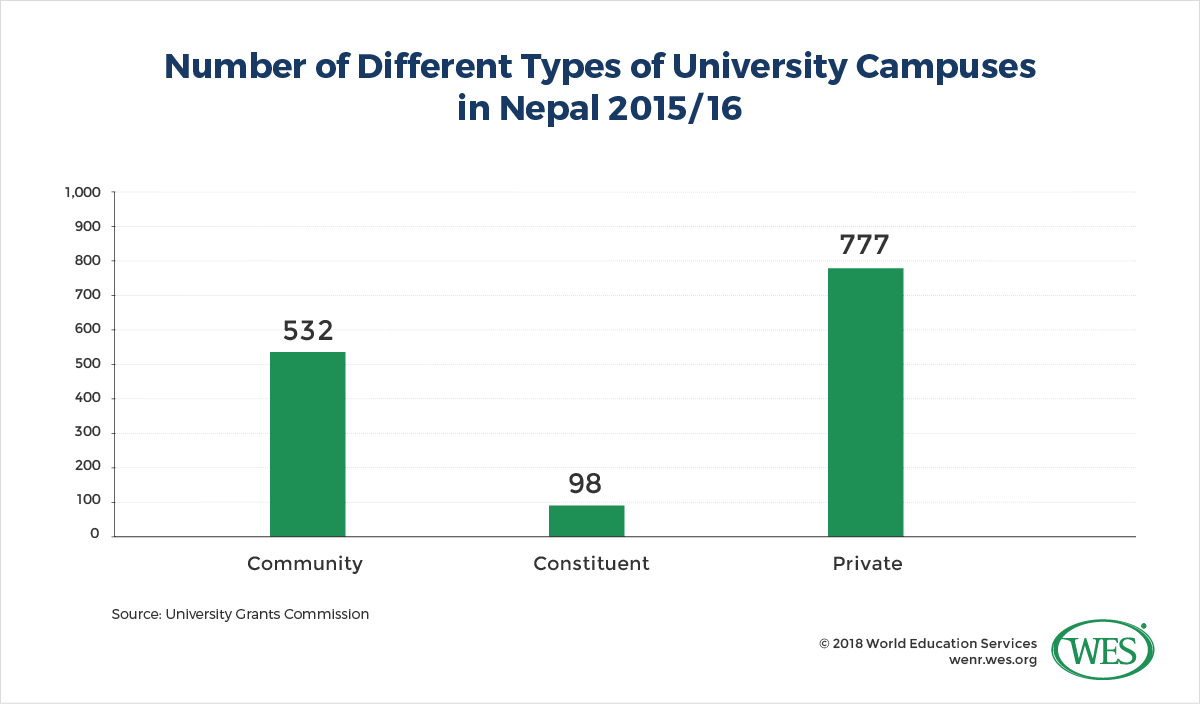

And while all universities are technically public institutions, their campuses (i.e., colleges) are often privately owned. There are two types of campuses/colleges in Nepal:

- Constituent campuses/colleges (directly managed and financed by a university), and

- Affiliated campuses/colleges: institutions that offer programs that lead to a degree awarded by the affiliated university, but are funded and managed externally.

Affiliated campuses/colleges can be privately owned or publicly subsidized by local communities. Community campuses charge tuition fees, but also receive grants from the UGC. Private campuses, on the other hand, derive all of their funding from student fees. This means that private campuses have a higher degree of autonomy and greater flexibility [28], even though their academic offerings must still be tailored to the degree programs of their affiliated universities, which determine curricula and assess student performance through external examinations.

Many of the private colleges are also much better-funded and have better facilities and equipment. At the same time, the high tuition fees at private colleges make many of them elitist institutions inaccessible to large parts of the population. The for-profit nature of these colleges also makes them susceptible to academic commercialization and an emphasis on quantity over quality [84].

The number of campuses/colleges in Nepal has grown strongly in recent years—705 new campuses were established between 2005/06 and 2012/13 alone [28]. As of 2015/16, there were 777 private, 532 community, and 98 constituent colleges [43] throughout the country, with the overwhelming majority of them (82.5 percent [43]) being affiliated to Tribhuvan University. 35.6 percent of tertiary students were enrolled in private colleges, 30.7 in community colleges, and 33.7 percent [43] in constituent colleges.

Quality Assurance and Accreditation

Public HEIs in Nepal are established by act of parliament on the recommendation of the UGC and are subsequently overseen by the UGC. The main function of the UGC is the disbursement of government funds (grants) to public institutions. Grant recipients need to meet set quality criteria in order to receive government funding and are audited for compliance. Private campuses, on the other hand, are not overseen by the UGC, but by the affiliated universities. They have full management autonomy, including in matters like the recruitment of teaching staff and the setting of tuition fees.

Internationally, Nepal’s universities are usually not regarded to be of very high quality [38]. While not necessarily a reliable proxy for quality, the standard world university rankings, for instance, do not include a single Nepali university.

In an attempt to increase quality in Nepal’s rapidly expanding higher education environment, the UGC in 2007 established a Quality Assurance and Accreditation Committee (QAAC) tasked with the accreditation of academic institutions and programs. Accreditation by the QAAC is granted for five-year periods. To qualify for assessment by the QAAC, HEIs must be affiliated with a university, must have offered programs for five years (or “produced at least 2 batches of graduates”), and 50 percent of its teaching staff, including the director and department heads, must be full-time professors [86]. Accreditation by the QAAC is strictly voluntary, however, and remains insignificant in Nepal as of now. Only 19 HEIs [87] held accreditation in 2018.

Student Population

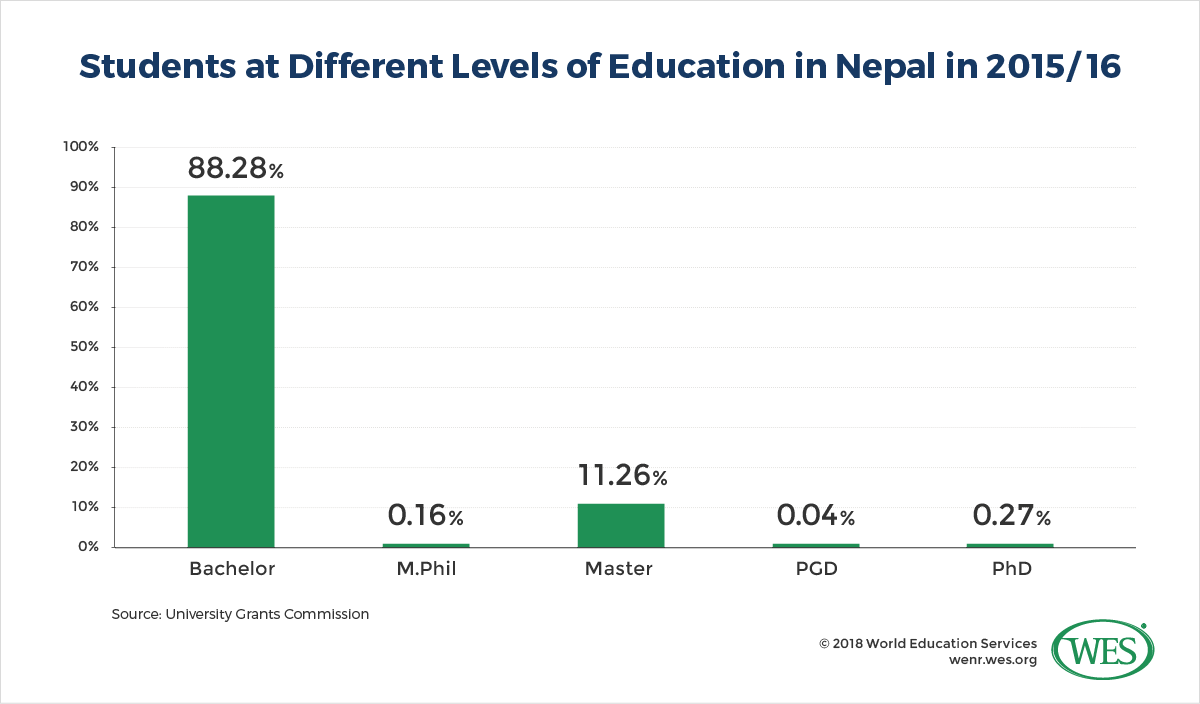

The number of tertiary students in Nepal has increased by 407 percent between 2000 and 2013, from 94,041 students to 477,077 students in 2013 (UIS). Since then, however, the number of students has leveled off and fallen to 361,077 students in 2016. The overwhelming majority of these students (88.3 percent [43]) were enrolled in bachelor’s programs in 2016. The number of graduate enrollments remains small and accounted for only 11.3 percent at the master’s level and less than 0.5 percent in advanced graduate and doctoral programs. This is reflected in the types of academic programs on offer in Nepal. In 2010/11, fully 80 percent of HEIs offered only bachelor’s programs, while 19 percent also offered master’s programs and only the main university campuses (less than one percent of all campuses) had Ph.D. programs in place [28].

Most students (78.8 percent) were enrolled at programs offered through Tribhuvan University, followed by Pokhara University (7.2 percent), Purbanchal University (6.5 percent) and Kathmandu University (4.6 percent [43]). The most popular majors were management (42.2 percent), education (24.8 percent), and humanities and social studies (10.7 percent [43]). The comparatively low enrollment rates in professional disciplines like medicine or engineering have been attributed to the poor preparedness of high school graduates for technical fields, and the fact that these programs are costly to operate and therefore only offered by a small minority of institutions, which usually charge high tuition fees [28].

Another problem is a low overall graduation rate in tertiary education. Pass rates in Nepal vary strongly by institution and program, but are low on average. At Tribhuvan University, where the vast majority of Nepal’s students are enrolled, the pass rate in bachelor’s programs stood at only 26.6 percent [43] in 2015/16. Marginalized groups and rural populations also continue to have less access to tertiary education than urban populations and members of upper castes. While gender parity has been achieved [43], the enrollment ratio in higher education among disadvantaged groups like Dalits was in 2010/11 still disproportionally low [28].

Education Spending

Government spending on education in Nepal has declined in recent years. Government expenditures on education as a percentage of GDP dropped from a high of 4.6 percent in 2009 to 3.7 percent in 2015 (World Bank [89]). Education expenditures as a percentage of total government spending, likewise, decreased from 25.5 percent in 2008 to 17.1 percent in 2015 (World Bank [90]). Government spending per tertiary student plunged by almost 82 percent [91] between 2000 and 2015.

When taking into account private expenditures, overall expenditures on education in Nepal have slightly increased over the past years. Aggregating public and private expenditures, UNESCO found [92] that total education spending as a percentage of GDP increased from 8.9 percent in 2008/09 to 9.3 percent in 2014/15. What these numbers demonstrate is that education expenditures in Nepal are increasingly borne by private sources. More than half of all education funding in 2014/15 (56.3 percent [92]) came from private households and, to a lesser extent, aid organizations.

Private expenses are primarily occurred in the school system, but increasingly in tertiary education as well. Kathmandu University, for instance, currently charges first-year undergraduate students fees totaling 211,400 Nepalese rupees [93] (USD $2,036). But since disposable income in Nepal is scarce, and the government-funded Tribhuvan University enrolls the vast majority of students, low public spending levels as they stand today will likely not be sustainable [28], given that larger youth cohorts are expected to enter the education system over the coming years.

Admission into University

The minimum admission requirement for tertiary degree programs is generally the National Examination Board Examination Certificate (or a similar 10+2 qualification like the Higher Secondary Education Board Examination Certificate or a Proficiency Certificate). Beyond that, admission requirements vary by institution and program. Entrance examinations are common for engineering and medicine programs, but not used across the board in all disciplines. Tribhuvan University uses entrance exams in professional and technical fields and has sought to introduce entrance exams in other majors, but these efforts were met with protests [28] by Nepal’s student unions. Other universities like Kathmandu University, on the other hand, use competitive entrance examinations in other disciplines.

Degree Structure

Bachelor’s degree

Bachelor’s degree programs in standard academic disciplines can be three or four years in length with a trend towards extending more programs to four years. Three-year programs are primarily offered in liberal arts, humanities, and social sciences, whereas programs in technical fields, agriculture, or nursing are more often four years in length. Curricula are usually specialized in the field of study with very limited general education requirements. Common credentials awarded include the Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science, but degree certificates may simply specify the name of the credential as “Bachelor’s degree.” Most programs are run on an annual system with year-end examinations, although Tribhuvan University has recently started to introduce a semester-based system on some campuses. Other institutions like Pokhara University [94] have already fully switched to a semester-based system.

Graduate Education

Master’s degree programs require a bachelor’s degree for admission. They are usually two years in length and commonly studied in the same discipline as the bachelor’s degree. A thesis is often required, although not mandatory in all programs.

Another credential awarded at the graduate level is the Postgraduate Diploma, which is a one-year post-bachelor program, often offered in more applied majors, but also in other fields like women’s studies, for instance.

The Master of Philosophy (M.Phil.) is an advanced graduate degree that requires a master’s degree for admission. Programs are usually three semesters in length and require preparation of a thesis. M.Phil. degrees prepare students for academic teaching careers and further doctoral studies and may be required for admission into some Ph.D. programs.

The Doctor of Philosophy is the highest academic degree in Nepal. Programs are three to five years in length and require a master’s degree or M.Phil. in a related discipline for admission. Ph.D. programs are usually research programs that entail a dissertation, but no additional coursework.

Professional Education

Professional entry-to-practice degrees in disciplines like medicine, dentistry, veterinary medicine, or architecture are long single-tier bachelor’s degree programs of five- to six-year duration. Medical and dental programs are only offered at faculties and institutions that are approved by the Nepal Medical Council, of which there are 21 medical faculties and colleges [95] and 5 dental faculties and colleges. Entry is generally based on the National School Board Examination Certificate (or equivalent qualification), but admissions are competitive and require passing of additional entrance examinations.

Medical programs lead to the Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS). These programs are most commonly five and one-half years in length, including a pre-medical component and a one-year clinical internship. Dental programs are usually five to five and one-half years in length, including a clinical internship, and conclude with the award of the Bachelor of Dental Surgery. In order to practice, graduates must pass the licensing exams of the Nepal Medical Council [96]. Graduate medical education in medical and dental specialties typically involves a further three years of training, concluding with the award of the Doctor of Medicine or Master of Dental Surgery.

Study programs in veterinary medicine are only offered at a small handful of institutions [97] in Nepal. Programs are between five and six years in length and lead to the Bachelor of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry.

The standard professional degree in law is the Bachelor of Laws, which is earned upon completion of a three-year graduate program, or a five-year program after high school. Licensure to practice law practice requires the passing of the bar exams of the Nepal Bar Council [98].

Teacher Education

Educational requirements for teachers in Nepal vary by level of education. While it is unknown how the current reforms in basic and secondary education will impact requirements for teachers, elementary school teachers could, as of recently, still teach with a 10-year Secondary School Leaving Certificate (SLC), as long as they also completed a practical teacher training program of at least ten months [54]. Lower-secondary teachers could teach with a Proficiency Certificate in Education or a 10+2 upper-secondary qualification plus 10 months of practical training [99]. Upper-secondary teachers, on the other hand, require a Bachelor of Education degree. These degrees can be earned either as direct-entry degrees after high school, shortened two-year programs for holders of a Proficiency Certificate in education, or as one-year “top-up” qualifications for holders of bachelor’s degrees in other disciplines [54].

Higher Education Grading Scales

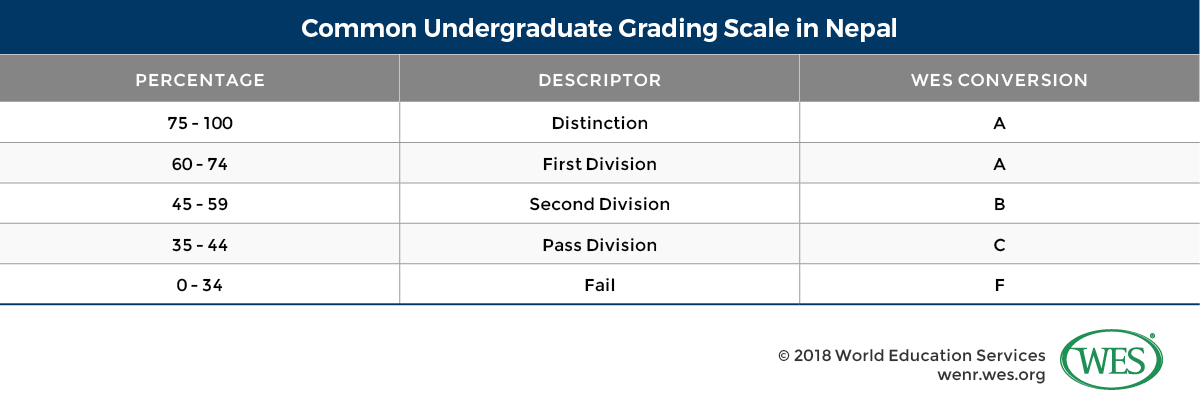

There is no single nationwide grading scale in use in tertiary education in Nepal. Institutions use different grading scales, ranging from A to F letter-based scales to 0-100 percentage-based scales. Tribhuvan University is switching to letter grade systems in its graduate programs, but as of recently still used percentage-based scales at the undergraduate level. One of the more common grading scale variations is listed below.

WES Documentation Requirements

Secondary Education

- National Examination Board Certificate, Higher Secondary Education Board Certificate (HSEB), or any other 10+2 certificate – sent directly to WES by the Board.

TVET

- Photocopy of Certificate/Diploma – submitted by the applicant

- Academic Transcript (Mark Sheets) – sent directly to WES by the Council for Technical Education and Vocational Training

Higher Education

- Photocopy of Degree Certificate – submitted by the applicant

- Academic Transcript (Mark Sheets) – sent directly by the institution attended

- For completed doctoral degrees – a written statement confirming the award of the degree sent directly by the institution

Sample Documents

Click here [101] for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- National Examination Board Examination Certificate

- Diploma in Engineering, CTEVT

- Bachelor of Arts, Tribhuvan University (3 years)

- Bachelor of Science, Tribhuvan University (4 years)

- Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery, Kathmandu University

- Master’s degree, Tribhuvan University

- Doctor of Philosophy, Tribhuvan University

1. [102] Students in all education sectors. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.).

2. [103] The National Examinations Board was created in 2016 [104] as a unified examinations board responsible for graduation examinations at the secondary level. Previously, these examinations were administered separately by the Office of the Controller of Examinations and the Higher Secondary Education Board.