Ashley Craddock, Editorial Advisor, WENR

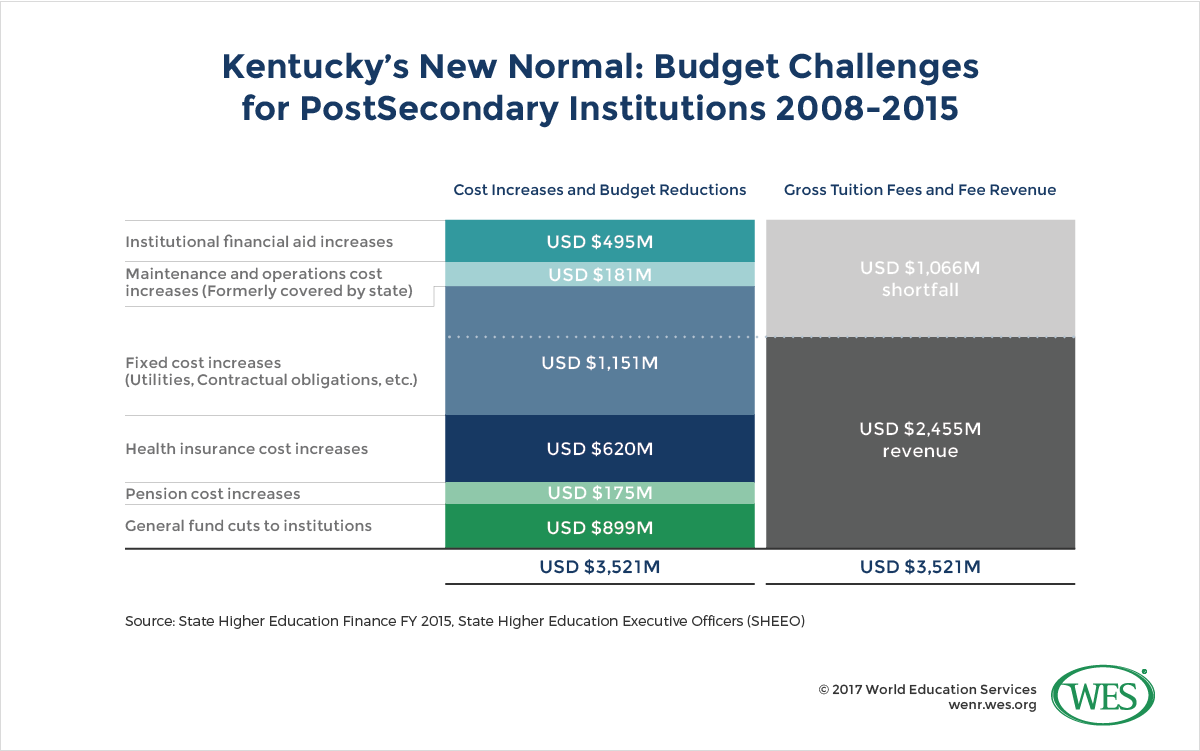

Kentucky’s public higher education system, like those of many states in the middle of the U.S., is in dire straits. Only five states have slashed per-pupil spending for higher education more than Kentucky in the last decade. In 2017, the state government allocated 26.4 percent less in per-pupil spending than it did in 2008.[1] 2016, data from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington-based, nonpartisan research institute. According to a report by the State Higher Education Executive Officers (SHEEO), the total shortfall faced by the state’s public higher education system was, between 2008 and 2015, more than USD $1 billion. Amid growing pension costs and declining revenues, the state’s eight public universities have seen enrollment declines, program cuts, and layoffs of staff and faculty.

Many local communities may lose local access to higher education altogether if budget shortfalls are not addressed. Given the scenario, it would be hard to imagine how administrators could ignore the more than one million foreign students flowing to the U.S., and the billions of dollars they are collectively willing to spend on their educations. International students, who typically pay full tuition and fees, are a promising source of new revenue for both universities and their surrounding communities. Those same students are potentially part of the solution to bigger problems in Kentucky: an aging populace and a dwindling workforce.

What happens when international student interest in the U.S. dwindles, and how can administrators react? Those questions loom large at institutions throughout America. Nowhere is this more true than at institutions that are, like Kentucky, in the nation’s heartland.

The International Student Gambit

In January 2018, The New York Times [2] painted a clear picture of the challenges now facing many institutions:

Just [when] many universities believed that the financial wreckage left by the 2008 recession was behind them, campuses … have been forced to make new rounds of cuts, this time brought on, in large part, by a loss of international students.

Schools in the Midwest have been particularly hard hit — many of them non-flagship public universities that had come to rely heavily on tuition from foreign students, who generally pay more than in-state students.

The downturn follows a decade of explosive growth in foreign student enrollment, which … began to flatten in 2016, partly because of changing conditions abroad and the increasing lure of schools in Canada, Australia and other English-speaking countries.

Kentucky is among the states most at risk in this scenario. Indeed, the state’s public institutions of higher education were long at the forefront of the push to attract more international students– explicitly so. Consider:

- Western Kentucky University’s motto is “A leading American university with international reach.” In 2016, the New York Times [3] described the school as “at the forefront of efforts by universities across the country to increase foreign enrollment.” That fall, WKU enrolled 1168 international students [4].

- The University of Kentucky has been similarly aggressive. Prior to 2016, the institution’s College of Arts and Sciences signed contracts with the governments of Saudi Arabia, Oman, Brazil, and Ecuador [5], seeking to enroll English language students studying abroad.The contracts sought to offset budget constraints, and, by so doing, to allow the college to hire additional faculty and staff.

- Morehead State University, whose enrollments and fiscal stability are threatened [6] by the decline of the coal industry, heavily recruited Saudi students supported by the kingdom’s King Abdullah Scholarship Program, in part to offset a budgetary shortfall of USD $9.7 million.

Even when enrollment rolls were flush, these efforts were often ill-fated. One failure, detailed by the New York Times in 2016, was a Western Kentucky University pilot program to increase enrollments by waving admission requirements. Indian students were admitted by agents, who offered “on the spot admissions” to applicants. Applicants were not required to provide proof that their academic qualifications were authentic, and according to the Times, only 26 of 132 students admitted as part of the pilot met WKU’s English language requirements. The results were predictably poor: at least 25 students were asked to leave [7] before their first year was up – a considerable hardship for affected students and their families, and a blow to WKU’s reputation.

But WKU was not alone in its missteps. The University of Kentucky was caught similarly off guard when a 2016 crash in oil prices led to the decimation of government scholarship programs funded by oil-rich countries like Saudi Arabia, Oman, Brazil, and others. “[International student tuition] was a revenue stream that was supposed to be very stable,” one University of Kentucky administrator told the Lexington Herald-Leader in 2016 [5]. “[The school’s College of Arts and Sciences] grew staff and lecturers to support that function.” The staff had to be cut once those dollars were gone.

Morehead State was hit similarly hard by the decline in energy prices. “MSU projected to lose over $13.5 million in the next four years after Saudi Arabia pulls funding [8],” said one local headline in 2017. The prospect of layoffs – estimated at 100 – was inevitable.

Such layoffs and belt-tightening maneuvers are only likely to become more common. In February 2018, the National Foundation for American Policy issued a policy brief [9] stating that, “the number of international students enrolled at U.S. universities declined by approximately [four] percent between 2016 and 2017, according to an analysis of U.S. Department of Homeland Security data. More than half of the decline in enrollment can be attributed to fewer individuals from India studying computer science and engineering at the graduate level in 2017. The number of international students from India enrolled in graduate-level programs in computer science and engineering declined by 21 percent, or 18,590 fewer graduate students, from 2016 to 2017.

While such findings present a challenge for all institutions, the threat is particularly profound for those in the middle – in the middle of the country, in the middle of the quality spectrum; and in the middle of the selectivity spectrum. Kentucky institutions fit all these descriptors.

Tackling the Higher Education Budget Crisis in Kentucky: A Survey of Tactics

Public institutions in Kentucky have cast about for a range of ways to address the budgetary crisis. These include:

- Tuition increases: As of 2017, Kentucky institutions had raised tuition by almost 37 percent in less than a decade. These increases have amounted to roughly $3,684 more in annual average tuition for local students. [2] Report: Kentucky’s higher ed funding crisis among nation’s worse,” Ronnie Ellis, CNHI Kentucky In 2017, increases of up to 35 percent threatened to drive in-state undergraduate tuition at the University of Kentucky above USD $12,000 for the first time.

- Investments: Western Kentucky University’s Crown Heights Foundation and the Murray State Foundation have invested heavily in bonds, mutual funds, and traditional stocks – relatively safe bets for bolstering endowment funds. Other institutions, including the University of Kentucky and the University of Louisville, have taken bigger risks, investing in “exotic, expensive and risky” hedge funds, which have, by and large, drastically underperformed, according to the Kentucky Center for Investigative Journalism.JAMES MCNAIR [10] May 25, 2016 http://kycir.org/2016/05/25/big-investments-and-underwhelming-results-at-kentuckys-universities/ [11]

- New delivery models: Eastern Kentucky University is exploring expanded online offerings [12] as a potential source of new revenue.

- Cost-cutting: Staffing, programs, and more have taken hits at the state’s eight public universities. In 2016, for example, Northern Kentucky University eliminated 63 empty faculty and staff positions, and laid off six faculty and three dozen staff, while Morehead University required all faculty and staff to take unpaid leave. The same year, Eastern Kentucky University instituted a hiring freeze and revamped HR policies to save money. In 2017, the university announced [13] 180 staff layoffs as part of an effort to get control of a USD $11 million deficit.

Recommendations for Surviving and Thriving: Diversification, Student Supports, Community Outreach, and More

The challenge facing mid-tier, mid-country public institutions such as those in Kentucky is as easy to state as it is difficult to execute: Bolster the bottom line. The strategies for doing so range from finding new ways to build donor-supported endowments, to working toward a more mature approach to internationalization that focuses appropriately on diversified recruitment strategies; to providing more effective ways to understand and support the international students already on campus. It also entails ensuring that local communities understand the connection between international enrollments and community benefits.

As a starting point, it’s important for university administrators in charge of international recruitment to know how to deploy scarce resources to get the maximal return on their investment in recruiting. This demands understanding the metrics that are most useful for predicting the returns on investment [14], over time, of any given recruitment effort.

It’s also important to find creative diversification strategies. Key among these are creative approaches to penetrating strong markets, such as China and India. Outbound students from these countries, long top senders to U.S. campuses, have begun to explore new destinations other than traditional magnets like the U.K. and the United States. That raises the importance of understanding how to approach Tier II and II cities in China [15], as well as those in India [16].

Administrators should also seek to bring the importance of international students – and the benefits they offer to local communities — to a greater level of public awareness as part of a broader effort to compel policymakers and politicians [17] at the state, local, and federal levels. As economist Giovanni Peri has noted [18], “While failure to integrate talented foreign-born students is costly at the national level, effects are most acute at the local level. Local universities compete to attract top-tier students, and local economies subsidize their education. Yet once this capital is produced at local universities, federal immigration policy causes its dissipation and loss of potential contributions.” Most acute, notes Peri, is the loss of contributions in tax revenues. Ensuring that local policy makers and host communities view international students as potential economic contributors is key to countering the perception that they are stealing seats that should go to local students.

Last but not least is an ongoing effort to supporting students now on campus. WES research has found that the experience of international students already on campus is a crucial domain of both recruitment and retention [19]. This means that institutions should seek to:

- Obtain deeper insights into international students’ needs by country of origin

- Provide adequate research opportunities, opportunities to build academic and social capital, provide adequate career counseling, and more

- Design a cohesive, cross-departmental plan of action that includes a range of supports

At a time when anti-immigrant and nationalists sentiments are on the rise, it also means that administrators should engage in a number of tactics designed to directly tackle such challenges head on. Nine of these are detailed in this month’s WENR article, Nine Actions to Help Students Navigate the Effects of Uncertainty about the Travel Ban [20].

References

| ↑1 | 2016, data from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington-based, nonpartisan research institute. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Report: Kentucky’s higher ed funding crisis among nation’s worse,” Ronnie Ellis, CNHI Kentucky |

| JAMES MCNAIR [10] May 25, 2016 http://kycir.org/2016/05/25/big-investments-and-underwhelming-results-at-kentuckys-universities/ [11] |