Bryce Loo, Research Associate, WES

[1]

[1]

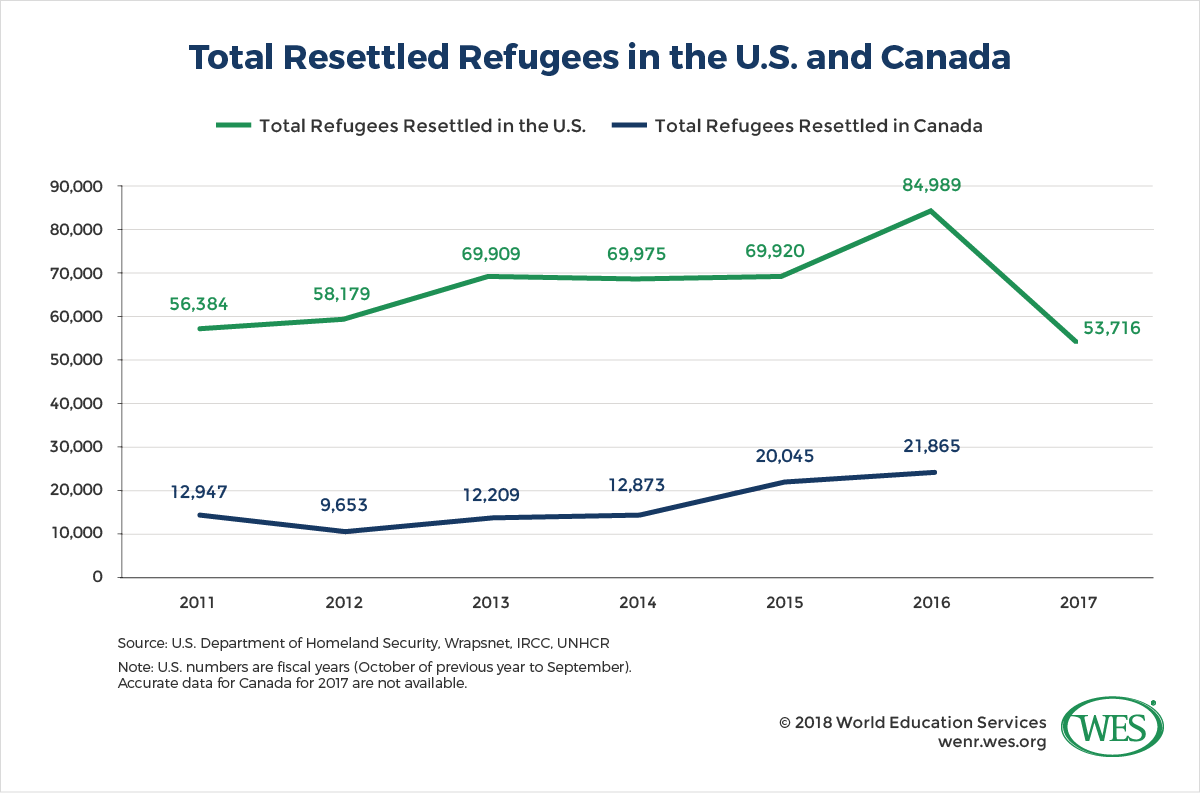

In the last few years, since the refugee crisis crested in Europe [2] in 2015, much of the world’s focus has been on the over 65 million people [3] who have been displaced worldwide — more than the whole population of the United Kingdom. The global higher education community has grappled with how to respond to the crisis in turn, including in how Western countries [4] can deal with a large influx of both asylum seekers and resettled refugees.

A large amount of attention has been given to Syrians, and for understandable reasons: Syria currently produces the largest number of refugees [5], and the news coverage of the civil war in that country is often shocking. And when it comes to higher education and the use of university degrees toward skilled employment, Syria has produced a large number of highly educated refugees [6], a fact that has spurred higher education institutions and providers worldwide to focus on aiding this particular group of refugees.

However, Syrians are far from the only refugees worldwide. Numerous other countries have experienced enough conflict, persecution of various groups within the country, natural disasters, and other turmoil to cause many to flee their homes. Many conflicts in the world have been taking place for far longer than the Syrian Civil War.

Take, for instance, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (often known as “DR Congo” or “DRC” for short), which has experienced waves of conflict since its independence [7] from Belgium in 1960, with the worst beginning in the aftermath of the genocide in neighboring Rwanda [8] in 1994. That conflict has produced millions of displaced people – both internally and externally – as well as enormous numbers of casualties.

This article will provide a look at three countries that produce large numbers of refugees and asylum-seekers that are lesser known: Iran, Bhutan, and Eritrea. All three send significant numbers of displaced people to the United States and Canada. Not only do they represent three different areas of the world – the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa, respectively – but they also have very different circumstances.

In each case, there is an overview of the situation in each country, with a look at significant historical and current issues causing turmoil. Then, there is a look at the main flows of refugees and asylum-seekers out of the country with specific attention on flows into North America. And finally, there is an examination of the education levels of individuals leaving the country – as much as is known – and any issues related to credential evaluation. In this way, higher education institutions and those working with refugee students and professionals can gain some basic information in assisting individuals with establishing educational and professional lives in new countries.

Iran

Large numbers of Iranians have fled the country, often in successive waves, throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries, especially since the 1979 revolution that brought in a hardline theocratic Shia Islamic government.

Background to the Crisis

Emigration has been a major part of Iran’s recent history. Shirin Hakimzadeh writes [10] that there have been three main waves of Iranian immigrants since the 1950s:

- The first wave, until the 1979 revolution, was composed largely of those migrating for economic purposes, including many middle- and upper-class families searching for more opportunities, as well as many students [11]. During this time, Iran was among the largest sending countries to the U.S. However, during this period, a large number of religious minority groups, such as Bahá’ís and Jews, fled as well, as they were targeted for persecution under the shah.

- In the second wave, immediately after the revolution, various groups fled, including socialists, young men fleeing military conscription (particularly during the Iran-Iraq War [12]), and young women and sometimes their families fleeing the new regulations on gender, including the wearing of the face veil. Many of these individuals were highly-educated professionals.

- The third wave, from 1995 on, is broken down into two groups: the highly-educated and professional, and economic migrants. As a result of profound professional migration, Iran has one of the highest rates of brain drain in the world.

Today, there are a variety of reasons why individuals flee Iran. Persecution seems to be the chief reason. Analyst Connie Agius sums this up well [13]: “Iran is a dangerous place to be different. People are persecuted for political views, their race, gender, sexuality, and religion.” Homosexuality, for example, is a capital offense [14] in Iran, making LGBTQ+ individuals vulnerable.

It appears that many Iranians seem to leave for a complex mixture of fear of persecution – based on factors such as political dissent or being a member of a minority group – and economic reasons. There tends to be disagreement among experts and Western politicians over which are the predominant reasons. It’s important to remember also that many of Iran’s economic problems are rooted in Western sanctions against the country, as Agius points out [13].

Movement of Refugees and Asylum-Seekers

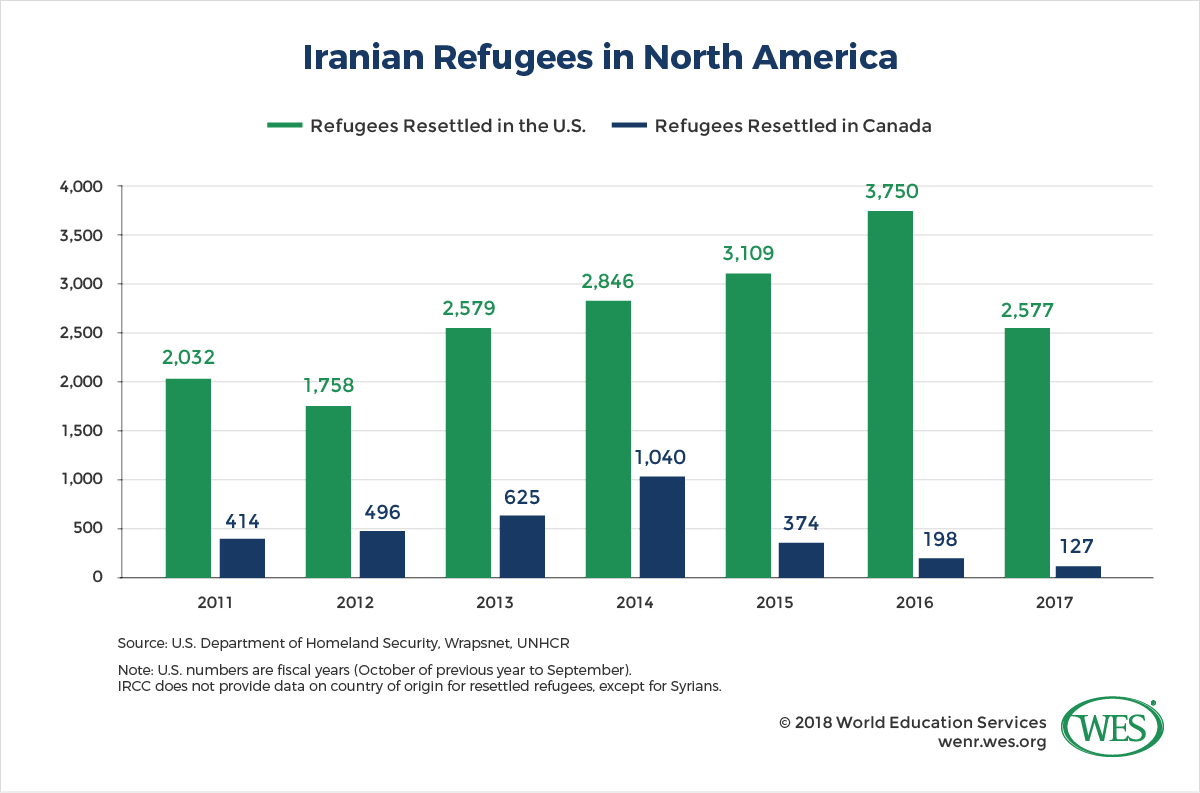

From 2014 to 2016, over 2,000 Iranian refugees were resettled to other countries each year, with the United States traditionally taking in the largest share. In fiscal year 2017, Iran was the eighth top sending countries of resettled refugees to the U.S., with 2,577 resettled, according to the U.S. State Department’s Refugee Processing Center [15], and it has been a long-time major sender of refugees. However, as of the end of March 2018, the number of Iranian refugees coming to the U.S. had dropped to a trickle, with only 31 arriving so far in fiscal year 2018. (Compare this to 1,295 Bhutanese refugees resettled at the same point in FY 2018.) The numbers of Iranians claiming asylum [16] in the U.S. had hovered around 500 to 600 annually from 2012 to 2016 but dropped off in 2017 to 381. All of this likely is at least in part due to the various iterations of President Trump’s travel ban [17], which have included Iran (along with mostly other Muslim-majority countries), and the dramatic scaleback [18] of the U.S. refugee resettlement program.

Canada is also a top destination, though its intake of Iranian refugees has been much lower than that of the U.S. in recent years, at least as indicated by data from UNHCR [19], the UN Refugee Agency. In 2014, Canada took in 1,040 Iranian refugees, but that number dropped to 374, 189, and 127 in 2015, 2016, and 2017 respectively. Some reporting [20] seems to indicate that the Canadian government’s prioritizing of Syrian refugees may have affected the numbers of Iranian resettled, but the overall reasons are not fully clear. Numbers of Iranian refugee claimants (asylum-seekers) granted asylum in Canada have been relatively modest, though Iran is in the top 25 countries of origin for claimants, according to Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) [21].

What is Known about Education and Credentials

Out of the three countries in this study, Iran has by far the highest levels of educational access, and a huge number of Iranian refugees and asylum-seekers are well-educated. In 2015, the gross enrollment ratio (GER) for upper secondary education in Iran was 84.5, roughly on par with Canada and the U.S., per the World Bank [22]. Similarly, the GER for higher education in 2015 was 71.9, not far behind the U.S. Also, Iranian refugees in the U.S. from 2009 to 2011 were well-educated: 55% of men and 46% of women in this group held bachelor’s degrees or higher, higher than the respective averages for U.S. citizens, according to a study by the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) [23].

However, discrimination in the education system – both basic and higher – is rampant in Iran. According to a report in [24]Deutsche Welle [24] ( [24]DW [24]) [24], Iran’s supreme religious leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, scoffed at UNESCO’s Education 2030 Agenda – part of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals [25] – which guarantees access to education for all people, regardless of characteristics such as ethnicity, religion, and gender. He considered it to be a Western conspiracy. As the final word on all governance issues in Iran, Khamenei’s lack of support for the Education 2030 Agenda effectively ties the hands of the more moderate President Hassan Rouhani from implementing it. Members of the country’s second largest religion, the Bahá’í faith [26], already are largely barred from the education system, though the DW article reports that most other religious minority groups are not. Women are also barred from studying a wide variety of subjects.

As noted, Baha’is are particularly singled out by the government. According to the DW article, “the Iranian government does not recognize Bahaism as a religion” – unlike Zoroastrians [27], Jews, and Christians – “because its founder, Baha’u’llah, lived after the Prophet Muhammad, whom Muslims believe was the last of the prophets. The Islamic Republic regards Baha’u’llah’s followers as apostates, and subjects them to numerous forms of repression.” They are effectively disallowed from accessing the mainstream education system. However, the Baha’is have found ways to continue their education. Most notable of these efforts, the Bahá’í Institute of Higher Education (BIHE) [28] was founded after Bahá’í students were banned from attending Iranian universities in the wake of the 1979 revolution. The institute, which is illegal in Iran, first provided instruction from mostly Bahá’í professors who were forced out of their jobs in Iranian universities. International reporting [29] indicates that many graduates of the BIHE have accessed top universities worldwide.

WES does not experience issues receiving and verifying credentials from Iran, with the exception of problems such as Baha’is.

Bhutan

A quiet Himalayan kingdom wedged between China and India, Bhutan [30] is generally not well-known to many North Americans. However, a significant number of Bhutanese refugees have been resettled to both the U.S. and Canada. More than 100,000 of an ethnic Nepali minority group in Bhutan were persecuted by the government and eventually forced out and into eastern Nepal in the early 1990s. In Nepal, they have lived in refugee camps but have been progressively resettled to different host nations [31], mostly the U.S.

Background to the Crisis

In the early 1990s, around 100,000 Bhutanese of Nepali descent, known as Lhotshampas, were stripped of citizenship during a campaign by the Bhutanese government [33] to narrowly define Bhutanese identity, against which many Lhotshampas protested. The narrowing definition included the banning of the Nepali language and ethnic dress [34]. Most Lhotshampas then fled across India to eastern Nepal [35], where they settled in camps.

Movement of Refugees and Asylum-Seekers

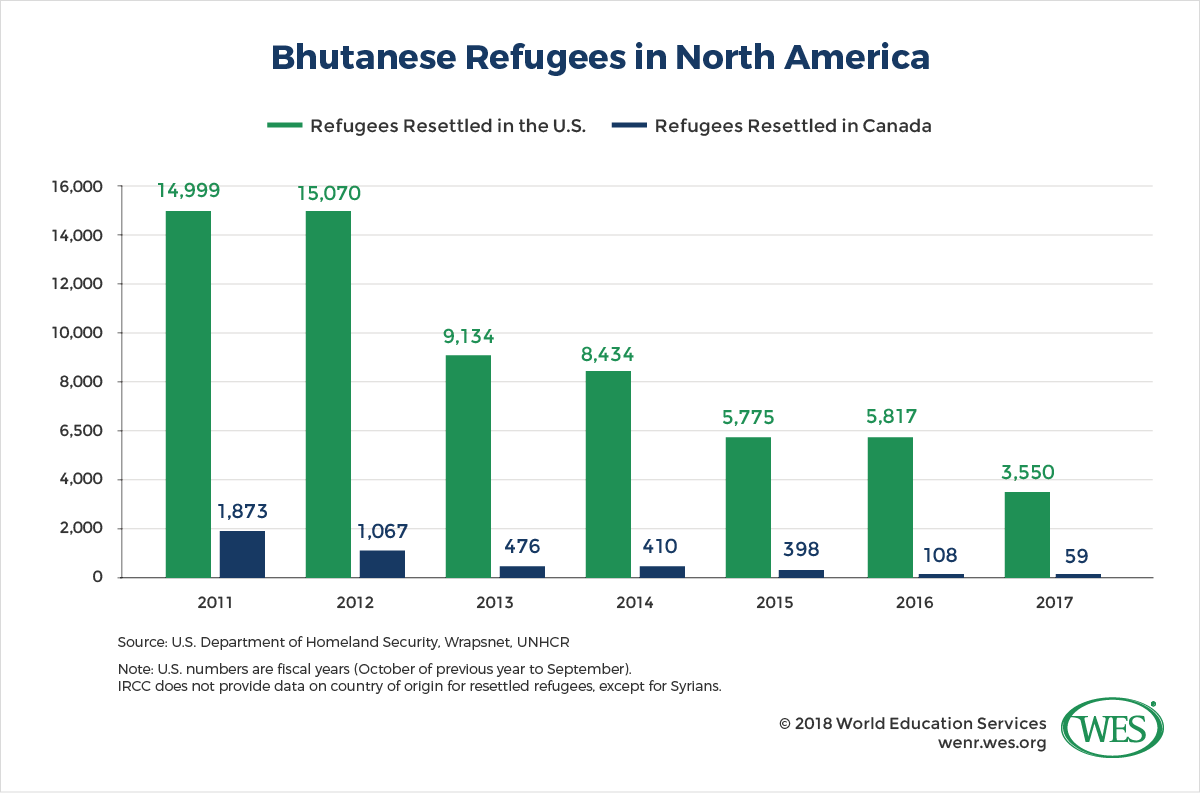

Most Bhutanese refugees in Nepal have been resettled to third countries [36] from seven camps. Eight countries – Australia, Canada, Denmark, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States – have resettled these refugees since 2007. The U.S. has taken in the largest number [36] – about 85% of all resettled Bhutanese refugees – and Canada has taken in the next largest number.

In 2015, the 100,000th refugee was resettled – in this case, to Ohio. Only about 18,000 remained after that point. The Bhutanese refugee camps in Nepal are largely considered to be down to the final group to be resettled. The vast majority have been resettled abroad, primarily to the U.S., but also to Canada, Australia, and a handful of other countries. Public Radio International (PRI) reports [37] that the Bhutanese refugee resettlement program has been deemed “a huge success.” Only two camps remain, as of late 2017. The Eurasia Review [38] reports [38] that likely only 5,000 Bhutanese refugees will remain in Nepal, once the final groups are resettled, some of which are awaiting appeal decisions following initial denials.

It’s unclear what will happen to these remaining Bhutanese refugees, including many older people who refuse to be resettled elsewhere. Bhutan has made it clear [31] that they will not be allowed to return, and Nepal has no intention of granting them citizenship. Most likely they will be able to stay but will not be fully integrated into society.

What is Known about Education and Credentials

Many Bhutanese refugees in Nepal have received education in the camps in a formal program known as the Bhutanese Refugee Education Program, or BREP [39]. Those who have feel more confident about their future prospects [40] after settling in the U.S. or other countries. According to Caritas Australia [41], the UN refers to the education in the Bhutanese refugee camps as among the best refugee camp education programs worldwide.

The Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) recorded a fairly detailed history of the BREP [39], as they were heavily involved in the program. They record that the program began as an informal program that took place outdoors at the very start of the refugee camps in 1991. The Catholic NGO Caritas began providing some funding. All seven refugee camps created schools that initially offered only primary education in four daily shifts, and eventually expanded to include secondary education by 1994. Eventually, the program was supported by UNHCR and several NGOs, including Caritas and JRS. They provided financial and technical support, including teacher training and professional development, to BREP. By 2000, “there were 42,000 students from pre-primary to post-secondary levels, with a voluntary teaching staff of more than 1,200 refugees. Nearly half of the students were female…”

The curriculum is a mixture of the Nepali and Bhutanese curricula [42]. The primary medium of instruction [39] is English, but students also learn Nepali and Dzongkha, the primary Bhutanese language. Many of the textbooks are produced by the program itself.

UNHCR, JRS, and Caritas managed to convince the Nepali government to officially recognize the education [39] that the students received through the program. As JRS further notes, “BREP served as one of the members of the District Examination Board and was even authorised to set additional papers especially for the refugees in the camps…”

The Refugee Center Online of Portland, Oregon, describes future educational opportunities [43] for the refugees in Nepal: “Many children from the camps go to boarding schools in Nepal and India for 10th to 12th grade. Students leaving for third-country resettlement are given School Leaving Certificates from their respective schools, which can be useful to their future school in their new countries.”

Despite there being a strong refugee education program, the Migration Policy Institute’s analysis [23] of integration outcomes for refugees who arrived in the U.S. from 2009 to 2011 concluded that Bhutanese refugees have relatively low levels of education. Over 40% of men and over half of women during this time did not have a high school degree.

In terms of credential evaluation, the country location of refugee education is not a concern for WES. If refugee students completed the Nepali curriculum and secondary school examination and can provide the appropriate academic documents, an evaluation report would be created based on the Nepali documents.

Eritrea

Eritrea became independent from Ethiopia in 1991 after a brutal war. Tensions with Ethiopia [44] continue to run very high, and the country has been running on a war footing as a result, with an indefinite state of emergency and reports of surveillance, networks of civilian informants, and torture, as well as mandatory, indefinite military conscription. The government is very secretive [45], and it’s difficult to know what is going on within the country. However, huge numbers of Eritreans have been leaving the country for years. It has one of the world’s highest outbound migration ratios; in fact, it is often considered “one of the world’s fastest emptying nations.” [45] Migrants fleeing Eritrea appear to be leaving for a combination of reasons, including lack of civil rights, avoidance of military conscription, and severe economic troubles.

Background to the Crisis

Eritrea was an Italian colony [47] from 1889 to 1941, when it was then occupied by the British and then given to Ethiopia as an autonomous region by the UN in 1952. Ethiopia formally annexed Eritrea in 1962, and a 30-year war between the two countries ensued.

In 1991, the war ended, with Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) winning independence, after toppling the Ethiopian president with the help of Ethiopian rebels. The Eritrean people formally voted for independence in 1993, and Isaias Afewerki, one of the leaders of EPLF, was installed as interim president. A constitution was ratified in 1997 but never implemented, and planned presidential elections never happened. Afewerki remains in power [48] to this day.

From 1998 to 2000, there was a border war between Eritrea and Ethiopia [47]. According to the Council on Foreign Relations [44], “tens of thousands were killed” in that war, which was precipitated by a border disagreement between the two nations that has never been resolved.

Eritrea suffers from crippling economic problems, partly due to international sanctions. The UN accused the Eritrean government of supporting al-Shabab militants in Somalia [44] in 2009 and imposed sanctions as a result. The sanctions remain in place despite findings from a UN report that the government stopped their support of al-Shabab in 2012, but the U.S., with its Security Council ability to veto, has not supported lifting sanctions.

Almost every aspect of Eritrean lives are regulated, due to the system of national conscription. Both men and women are conscripted, and this “national service” can be service in the army or often in various jobs – including professional jobs such as medicine and teaching – as well as manual labor. The pay is described as being extremely poor. An article in [49]The Guardian [49] describes this national service as “allow[ing] the government to treat each civilian as a modern-day serf for their whole life.”

Movement of Refugees and Asylum-Seekers

Some 5,000 Eritreans leave the country every month, as of 2016, according to the Council on Foreign Relations [44], making it the largest producer of refugees worldwide. Most Eritreans either go to neighboring countries, particularly Ethiopia, or they try to make it to Europe or Israel. The two main routes to the West are via the Sahara Desert to Libya, where smugglers ship them often in vessels of very questionable quality to Italy. Those who make it across to Italy – without dying in the Sahara or Mediterranean, or being kidnapped – usually then try to reach northern European countries such as Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The other main route is via Egypt and the Sinai Peninsula, where they often faced kidnapping by Bedouin tribes, on the way to Israel. Eritreans have been given prima facie status by the United Nations. This means that they are automatically considered to have asylum status if requested because of the situation in-country.

As of early 2018, the Israeli government has started issuing deportation notices [50] to Eritreans and other African migrants, with the focus, for now, on single men. This amounts to around 20,000 of the approximately 39,000 Eritreans and Sudanese in Israel. Upon receiving notice, migrants have 60 days to leave; the only direction given from the government is to either go to Rwanda or to return to their home countries.

From 2014 to 2017, 10,902 Eritreans were resettled to third countries by UNHCR [19]. The majority, at least until recently, were resettled to the U.S. According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security [16], 1,949 Eritrean refugees were resettled into the U.S. in 2016. By contrast, only 255 Eritreans were granted affirmative asylum in 2016, a very low number compared with China and several Central American countries, for example.

The Obama Administration had prioritized resettlement and affirmative asylum for Eritreans facing religious persecution [44], namely evangelical Christians. The Trump Administration is trying to increase deportations of Eritreans [51] from the United States and is even threatening to impose sanctions on the country for not accepting back deportees.

A fairly substantial number of Eritreans have claimed asylum in Canada. IRCC reports [52] 1,205 Eritreans filing asylum claims in 2017, the vast majority within Canada itself (rather than at a port-of-entry). However, recent headlines1 [53] have noted that there is an uptick of Eritreans who had been living in Israel making their way to Canada. Various groups, including Jewish and Israeli-Canadian as well as Eritrean-Canadian and refugee resettlement organizations, have been lobbying the Liberal Government to take in more Eritreans living in Israel as the Israeli government cracks down on African migrants.

What is Known about Education and Credentials

Educational indicators for Eritrea appear fairly weak. The gross enrollment ratio (GER) for secondary education in Eritrea was 23.1 in 2015, well below many other refugee-producing countries, per the World Bank [54]. At the higher education level, the GER is only 2.6. In other words, only a relatively small number of Eritreans receive secondary education, and very few go on to higher education. Likely, many Eritrean refugees and asylum-seekers are less educated. Moreover, UNICEF reports [55] that “the quality of education is also an issue” for the country.

Additionally, there are only eight higher education institutions in the country, according to a briefing from the European Commission [56]. The University of Asmara, located in the capital, is the primary institution and was the only one until 2003.

In WES experience, there are currently no known issues with receiving credentials, including issues related to the withholding of documents for political reasons. However, a January 2018 article in [57]Inside Higher Ed [57] reports that Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia face problems accessing academic documents for entrance into Ethiopian higher education because of “Eritrean rules that restrict issuance of original school certificates or diplomas to any citizen who cannot present evidence of having completed national service or having been exempted.” The European Commission briefing confirms this [56]. This appears to be similar to a well-known practice of Eritrean embassies and consulates [44] in major destination countries that exact a “tax” from Eritrean immigrants; if they do not pay this tax, they are denied consular services. In other words, refugees and asylum-seekers that fled Eritrea to avoid national conscription may be denied access to their documents. Or, it is possible that they may be charged large fees – ones that they may not be able to afford easily – for such services.

A Summary of the Three Cases

Iran, Bhutan, and Eritrea represent three very different cases of countries producing large numbers of refugees and asylum-seekers. Iran provides a case of a country from which many people flee because of minority status or political dissent. Similarly, many Eritreans flee because of not only political dissent but because of the lack of political and civil rights under an authoritarian regime. Bhutan represents a case of citizens who are forced out of the country and made stateless. All three of these cases differ even from that of Syria, which has produced huge numbers of displaced people through civil war.

Furthermore, the educational systems from which they come vary tremendously in quality, and the levels of education among refugees likely also vary. Iran is one country that has a strong education system with high participation, including among women, and as a result, many Iranian refugees and asylum-seekers are well-educated. By contrast, Eritreans are much less likely to be highly educated or from professional backgrounds. And Bhutanese refugees are a different case entirely: Many will have received reasonably good quality education from refugee camp education programs in Nepal. It is unclear, however, how well this education translates into integration into North American society.

Finally, access to and evaluation of credentials may or may not be an issue for individuals from these three countries. For some Iranians and Eritreans, it may indeed be an issue. Some religious minorities in Iran, particularly Bahá’ís, were forced to attend underground, unaccredited schools, as they were forbidden to attend mainstream education. Recognition of their education abroad may be more challenging, though many have gained access to top universities worldwide. Meanwhile, Eritreans may be denied access to educational and other important documents if they avoided national conscription. At the same time, Bhutanese refugees educated in camp programs may have taken the Nepali secondary school leaving examination and received appropriate paperwork. But what if they never took or passed the examination? Can their educational backgrounds still be recognized?

What This All Means

Refugees and asylum-seekers will come to North America and elsewhere with a tremendous diversity of backgrounds, but many will want – and ultimately need – to access further education and advance on to professional employment opportunities. Helping these individuals will provide better chances of their integration into North American society and enhance their ability to contribute meaningfully to their new communities and countries. But in order to help them, it takes a bit of understanding of where they came from and why.

1. [58] Paul Lungen, “Canada Welcomes Eritrean Refugees Coming Via Israel,” The Canadian Jewish News (CJN), February 6, 2017, https://www.cjnews.com/news/canada/jias-facilitating-immigration-eritrea-refugees-via-israel [59]; Paul Lungen, “Why Eritrean Asylum Seekers Are Leaving Israel For Canada,” The Canadian Jewish News (CJN), August 10, 2017, http://www.cjnews.com/news/canada/eritrean-asylum-seekers-leaving-israel-canada [60]; Kathleen Harris, “Canada Raises ‘Concerns’ Over Israel’s Mass Deportation Plans For African Migrants,” CBC News, February 19, 2018, http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-israel-eritrean-refugees-1.4538525 [61].