Makala Skinner, Research Assistant, WES

As the percentage of issued F-1 visas [1] continues to drop, many institutions within the U.S. are facing decreases [2] in their international student population and are looking to bolster their current recruitment strategies. While the cultural and financial value of international students on American campuses has long been recognized, the importance of a diverse international student body and particularly an economically diverse student body is often overlooked. Recruiting economically diverse international students allows schools to more efficiently focus their recruitment efforts and better predict incoming classes, resulting in a higher yield on resources invested in recruitment and admissions.

By coupling economic diversity with diversity of home country and admitting a cohort of foreign students originating from a variety of nations, higher education institutions (HEIs) are better positioned to weather tumultuous political and environmental events that may have negative repercussions on their schools. Examining student trends by socioeconomic status and country of origin in conjunction, rather than disparately, provides a more comprehensive understanding of student priorities and their likelihood of matriculation.

HEIs can increase the economic diversity of their student body by instituting an intentional and inclusive needs-aware admissions policy, strategically recruiting students whose priorities match institutional characteristics, allocating existing financial aid to students with fewer financial resources, and considering country context. To ensure economically diverse students thrive once on campus, HEIs should plan beyond financial considerations and explore ways to provide additional layers of support.

Benefits of International Student Diversity by Socioeconomic Status and Country of Origin

Diversifying international student populations by socio-economic status is rarely discussed, most notably because the conversation surrounding foreign students often centers on the financial benefits of those able to pay out-of-pocket tuition. Nearly half [3] of U.S. university and college admissions leaders, however, feel that schools are too reliant on foreign students who pay full tuition.

While it may sound counter-intuitive, recruiting from different socio-economic strata has many positive institutional effects. A survey [4] of World Education Services (WES) international students reveals clear school choice and priority trends based on students’ financial resources. These trends show differences between the number of applications submitted, preference of school location, and level of importance placed on availability of financial aid by students of differing financial means. HEIs can use this data to allocate financial resources strategically and predict which students are most likely to transition to enrollment by matching student trends with their institution’s characteristics. This vantage allows schools to leverage recruitment and financial resources in the most efficient way to produce the highest yield.

Additionally, selecting students from a multitude of countries in addition to varying socioeconomic strata protects schools from unpredicted changes in the market. Universities and colleges that host disproportionately large percentages of students hailing from only 1 or 2 countries hazard the stability of their long-term enrollment plan – for example, what may transpire should that country have a sharp decline in enrollment. When Saudi Arabia, responding to a 2016 crash in oil prices, scaled down a government scholarship for students pursuing their education abroad by making requirements stricter [5], HEIs in the U.S. experienced a 14.2% drop [6] in Saudi Arabian student applications from 2015-16 to 2016-17.

Likewise, many institutions in the U.S. are concerned about a downward trend in Indian student enrollment, with new enrollment at the graduate level seeing a 13% drop [7] from Fall 2016 to Fall 2017. This percentage is likely to fall further in Fall 2018 given a 28% decrease [1] in visas granted to Indian students in 2017. That decrease, coupled with a 24% reduction in visas issued to Chinese students, is particularly problematic considering India and China are respectively the number two and number one [8] senders of international students to the U.S.

By diversifying international students’ country of origin, HEIs can not only protect themselves from country-specific enrollment declines, but can capitalize on emerging markets as well. Schools can position themselves to benefit from large-scale recruitment in the future by identifying countries with growing economies and rising higher education demand. Ghana, for example, has experienced a nearly ten-fold growth in GDP [9] since 2000 and is seeing an increasing number of students pursuing tertiary education abroad [10] in recent years. This increased mobility is attributed, in part, to the rising number of students pursuing higher education and the limited availability of in-country HEIs providing high-quality education [10] — a classic case of demand exceeding supply. Institutions that begin to establish recruitment pipelines now may see greater application increases from these countries in the coming years.

There is value to admitting students diversified by socioeconomic status and by country of origin. Student priority trends exist within both categories, which can provide HEIs with helpful information. To capitalize on this information, HEIs can utilize these two data points in tandem with one another to discern an even clearer image of which students are well-suited to their institution and likely to matriculate if offered admission. This information allows HEIs to make more informed decisions in how they allocate their recruitment resources, offers of admission, and financial aid — not only making them more efficient, but also providing them with a competitive edge.

What HEIs can do to Increase Economic Diversity among International Students

Needs-Aware Policies

While the most elite HEIs [11] extend need-blind admissions policies to their international applicants, many institutions may be better served by implementing an inclusive needs-aware recruitment policy that consciously selects students from diverse economic backgrounds. The most apparent reasons for this are that needs-aware policies help HEIs predict their yearly budgets, ensure financial stability, and may allow schools to better distribute resources [12] by admitting higher-paying students to increase institutional ability to support low-income students.

Perhaps less evidently, a significant benefit of adopting a needs-aware model is that it may better achieve the goal of diversifying students by socioeconomic status. Though need-blind policies [12] are heralded as bearers of equality, in reality, this may not be the case. Wealthier families are able to invest in their students’ education, extra-curricular activities, and standardized test preparations in a way that lower-income families are unable to afford; since income is correlated with student performance in each of these areas, a need-blind policy may inadvertently filter out students from low-income backgrounds [12].

Predicting International Student Matriculation

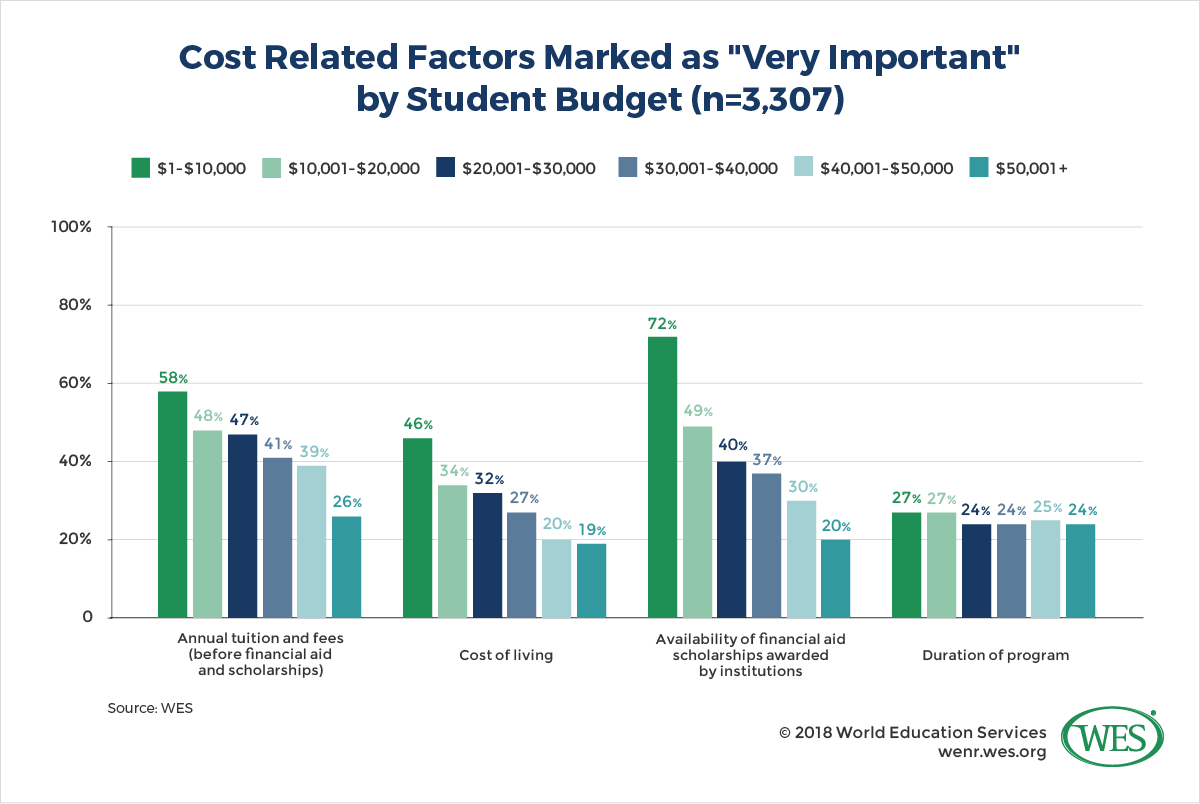

Perhaps the greatest benefit of recruiting economically diverse students is that it allows an institution to leverage its recruitment resources in the most efficient way while producing the highest results. Cornell University [11] reported that 90% of students who applied for aid and were offered financial support accepted their admissions offer compared with only 65% of admitted foreign students who were offered admission but did not apply for financial aid. Still lower, only 30% [11] of international students who applied for financial aid but did not receive any accepted their offer. Financial aid is an important determining factor for many students and it is correlated with a student’s financial resources; the fewer the resources, the more important financial aid becomes and vice versa. WES data [13] reveals that while only 20% of students with budgets of $50,000 or higher felt that institutional financial aid and scholarships were “very important,” this percentage more than tripled for students with a budget of $10,000 or less (72%) (see Figure 1). This pattern holds true across all cost-related factors.

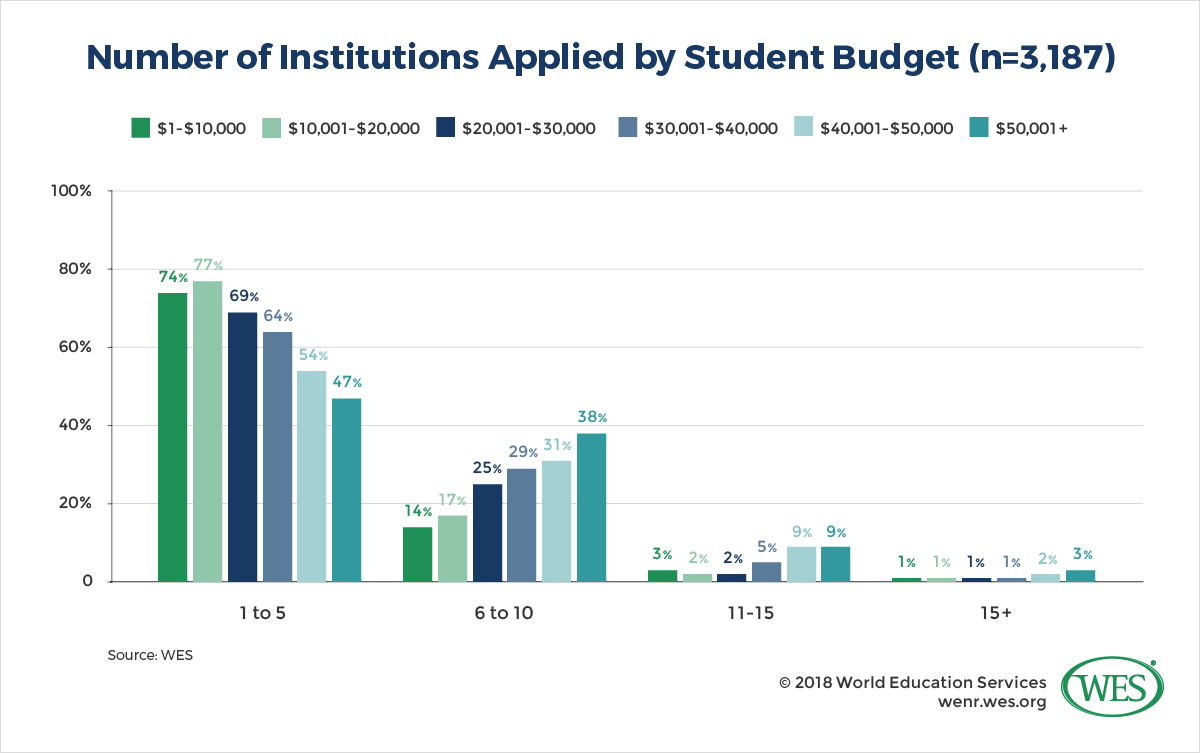

Matriculation rates are further influenced by the number of schools to which students apply. The greater a student’s financial resources, the more applications they completed; conversely, students with fewer financial resources applied to fewer institutions [13] (see Figure 2), making them more likely to accept an admissions offer. One strategy HEIs can use to increase applications from international students with fewer financial resources is to waive application fees [13].

Student application patterns also show that while students of all budgets apply to both public and private institutions, those with fewer resources apply to more public schools, and those with more resources apply to more private schools; this remains true even when applications are segmented [4] into reach, match, and safety schools. This may be good news for public institutions, which have borne the brunt of declining international student enrollment [2] numbers. According to an IIE snapshot survey [2], public institutions saw an 11.3% decline in new international student enrollment from Fall 2016 to Fall 2017 compared with only a 0.1% decline seen at private not-for-profit universities.

A school’s ability to predict its incoming international student class varies greatly by the economic diversity of its admitted cohort and, based on matriculation rates and school cost considerations by student budget, it becomes clear that one of the most effective changes HEIs can make is to provide financial aid to low-income international students. When New Zealand [16] subsidized Ph.D. tuition for international students, the number of foreign students entering Ph.D. programs more than doubled within the same year. Likewise, Denmark and Sweden [16] have seen new reductions in tuition fees encouraging higher numbers of newly-enrolled international students.

Supporting economic diversity among international students does not necessarily require a tuition reduction or an increase in the amount of scholarships offered, rather, it can mean evaluating how scholarships are currently dispersed and making changes to ensure the most effective use of school resources. Reallocating existing scholarships and financial aid strategically, such as by exchanging merit-based scholarships for need-based scholarships, could be a better use of funds. Since international students with higher budgets are less concerned about cost, offering need-based scholarships to lower-income students may increase matriculation rates more effectively than offering merit-based scholarships to higher income students.

Strategically Recruiting International Students by Socio-economic Status and Country

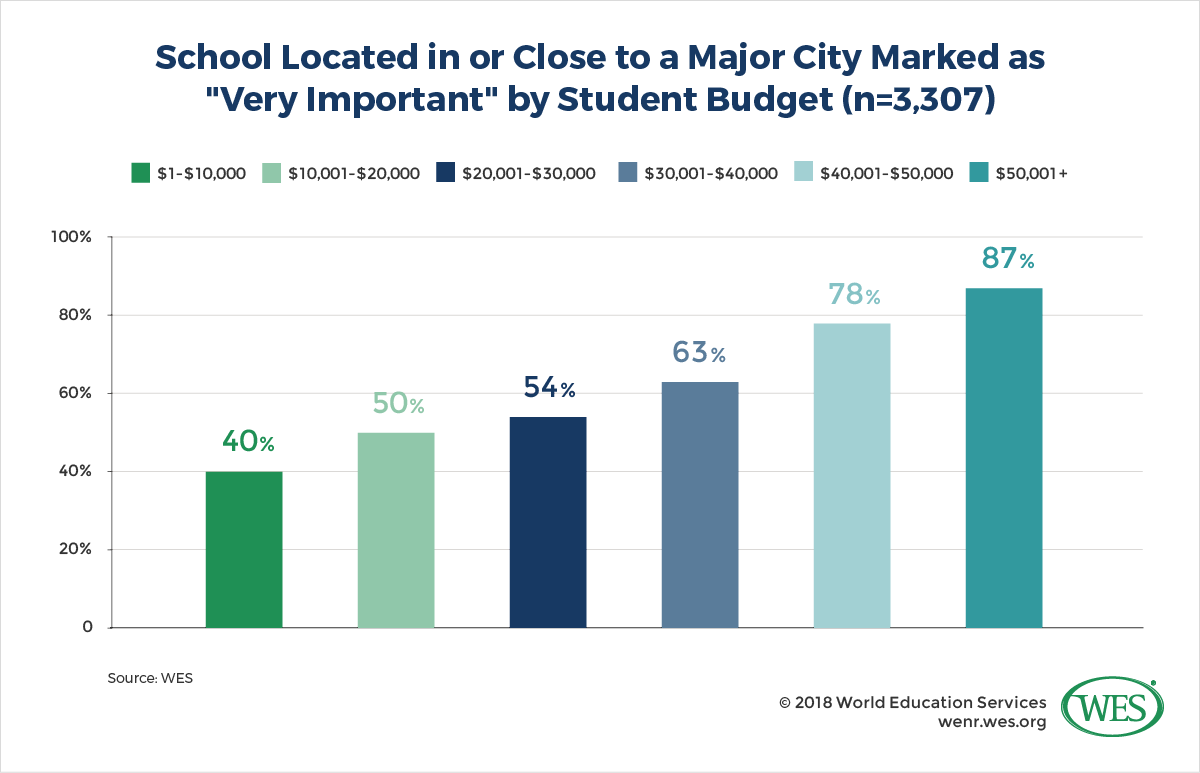

HEIs can more efficiently utilize their recruitment resources by examining prospective international students’ socioeconomic status, country of origin, and the associated student priority trends for each. With this information, schools can strategically allocate recruitment resources to international students best matched with their institutional characteristics. School location, for example, becomes more or less important based on a student’s financial resources. Students with fewer financial resources place less importance on being in or close to a major city; conversely, students with greater financial resources are significantly more likely to consider school location and its proximity to an urban area as “very important [4]” (see Figure 3). This provides an opportunity for institutions in rural and suburban locations [13] to increase their international student enrollment by offering scholarships to international students with fewer financial resources. Schools located in the Midwest [2] have been some of the most affected by the recent decrease in new international student and may be particularly well-placed to recruit economically diverse students.

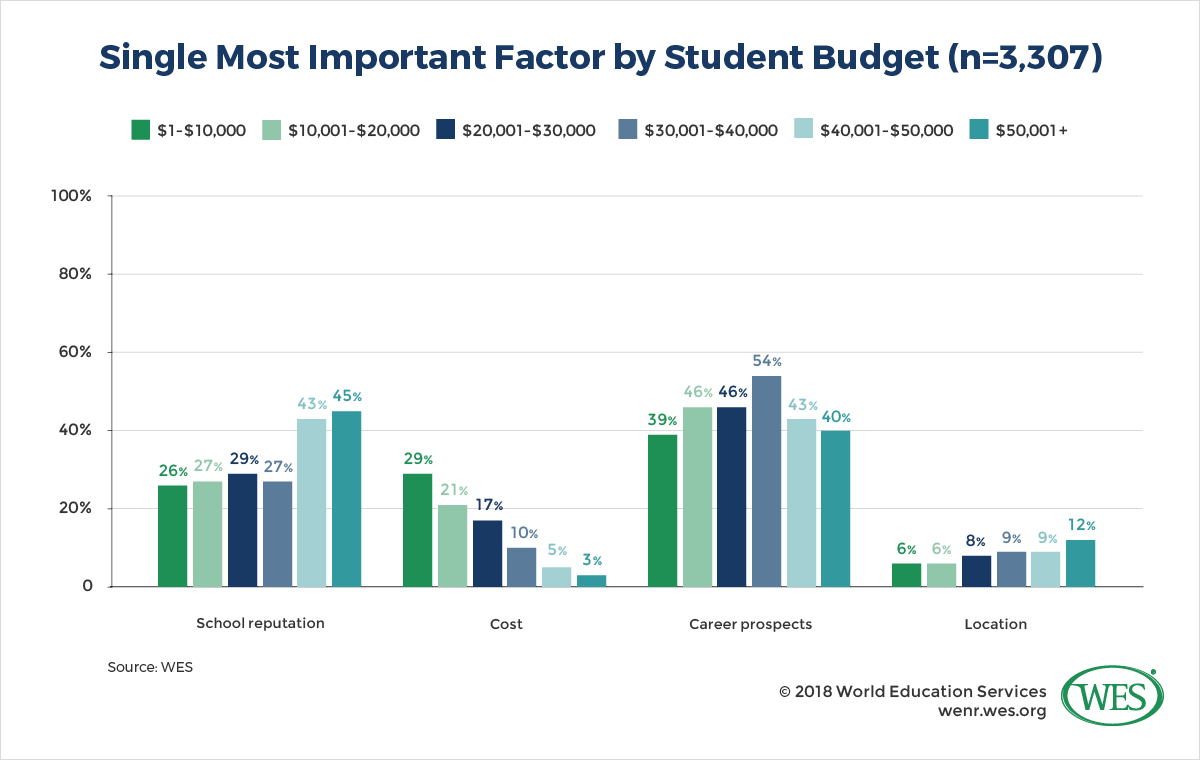

WES survey participants were asked to select what they considered to be the single most important factor when applying to American HEIs out of four choices: School reputation, cost, career prospects, and location. When the data is segmented by student budget, distinct patterns emerge. School reputation becomes less important, and institutional cost becomes more important the lower a student’s budget and vice versa (see Figure 4). HEIs whose name may not be known internationally could be especially well-served by recruiting lower-income students who place less importance on school reputation. Career prospects were rated highly across all resource brackets, meaning schools that have robust career services offices and are able to support international students in the job search are desirable to foreign students.

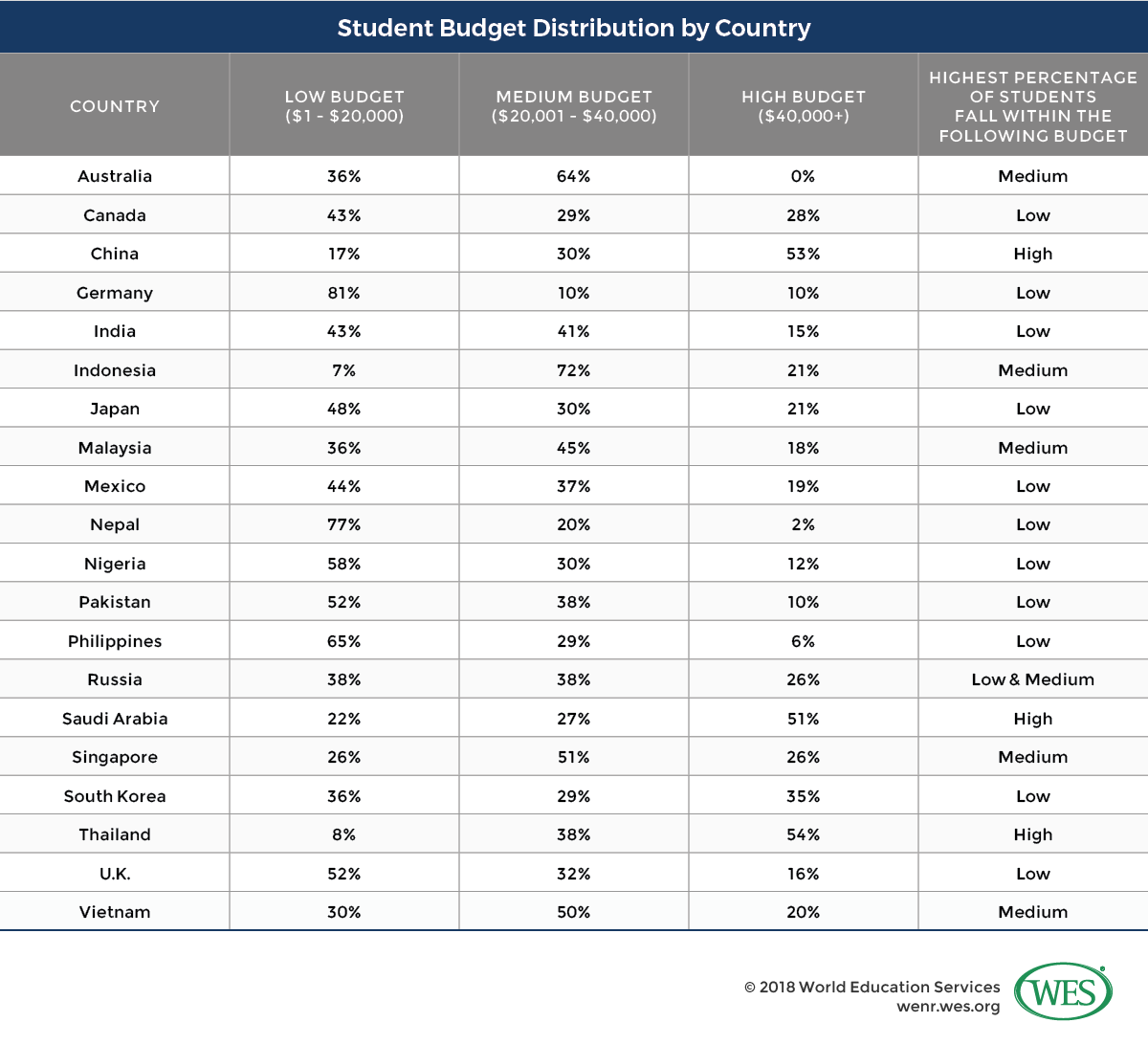

By analyzing the data by budget and country, it becomes possible for HEIs to identify where their recruitment resources may be best placed. When WES [4] survey participants’ budgets were collapsed into three categories- low, medium, and high- 12 of the 20 surveyed countries had more than half of all sampled students fall within the “low” budget category; Germany, Nepal, and the Philippines topped the list with the highest percentages of students with low budgets (see Table 1). Indonesia and Australia had the highest percentages of their applicants fall within the “medium” budget category compared with other countries, and Thailand and China had the most students with high budgets. When compared with students’ school priorities by country, HEIs can identify which locations have the highest percentage of students who match their schools’ characteristics; this could lead to increasing or decreasing recruitment efforts among certain populations or foraying into a new country altogether.

Chinese applicants, for example, value school reputation twelve times more than the cost of a school, and 53% of surveyed students had high budgets. Similar patterns appear for Indonesia and Singapore. On average, these students are less likely to be swayed by scholarships or financial aid offers over the school’s name. HEIs without international recognition may want to focus their recruitment efforts more seriously in other countries or specifically recruit low-income students from the aforementioned countries. Students from Vietnam, on the other hand, rated school cost more important than any other surveyed country, and are five times more likely to care about cost than either school reputation or location; 50% of these students fall within the medium budget category. Nearly half of all sampled students from the Philippines and Canada also rated cost as the number one factor in selecting an institution, and both countries had the highest percentage of their students fall within the “low” budget category. Students from Saudi Arabia cared the most about school location, and students from Nepal cared the least about it.

Given the decreasing percentages of new international students within the U.S., effectively utilizing institution resources has taken on even greater importance. As HEIs increase economic diversity within their institutions, there is potential for the applicant pool to increase, widening to include the previously under-tapped demographic of low-income students. The statistics included in this article are meant to be used as a tool that can help guide HEIs as they carefully consider where and who to recruit internationally. It is important to note, however, that the students who participated in the WES survey are individuals who already made it the college or university application process and may not be representative of all higher education students within their countries.

Beyond Finances

HEIs should consider the needs of international students from different socioeconomic strata in their long-term planning. Much of the conversation surrounding economically diverse students is restricted to funding, yet it is important to consider that students hailing from low-income contexts will likely need support as they navigate the application process, arrive on campus, and learn the soft skills with which their wealthier peers have already been socialized. Increasing international student economic diversity is more than simply offering admission; it also entails supporting their needs as they work towards their degree.

HEIs can pursue a multitude of avenues to achieve this end. They can expand or adapt existing programs that support low-income domestic students to include international students as well, or they can utilize Education USA [20], a U.S. State Department initiative that assists international students seeking to study in the U.S. Education USA [20] advises prospective students on everything from the application process to visas to financing their education and also assists HEIs by organizing college fairs, connecting domestic and international HEIs, and providing relevant information. In particular, it may be helpful for HEIs to connect with Education USA and request information about the Opportunity Funds Program, a program which helps low-income international students pay for initial costs such as testing and application fees and even airfare for eligible students in more than 50 countries [20].

Economically diverse international students bring extensive cultural expertise and diverse perspectives to American learning institutions. HEIs should not fall into the trap of assuming that the lack of soft skills often associated with low-income students equates to lack of knowledge. Students with fewer financial resources will draw on a breadth of personal experience and share unique insights in the classroom and in their research, not only bringing marginalized voices into a space where they may be heard, but also offering a more comprehensive body of knowledge for all change-makers to wield as they seek to improve the world.