Ann-Cathrin Spees, Credential Analyst, WES

A common perception in the United States is that it takes a college degree to get a good job.1 [1] More than 85 percent of 141,189 freshman students surveyed in 2015 [2] by the Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA, for example, stated that getting a better job was the most important reason to go to college.

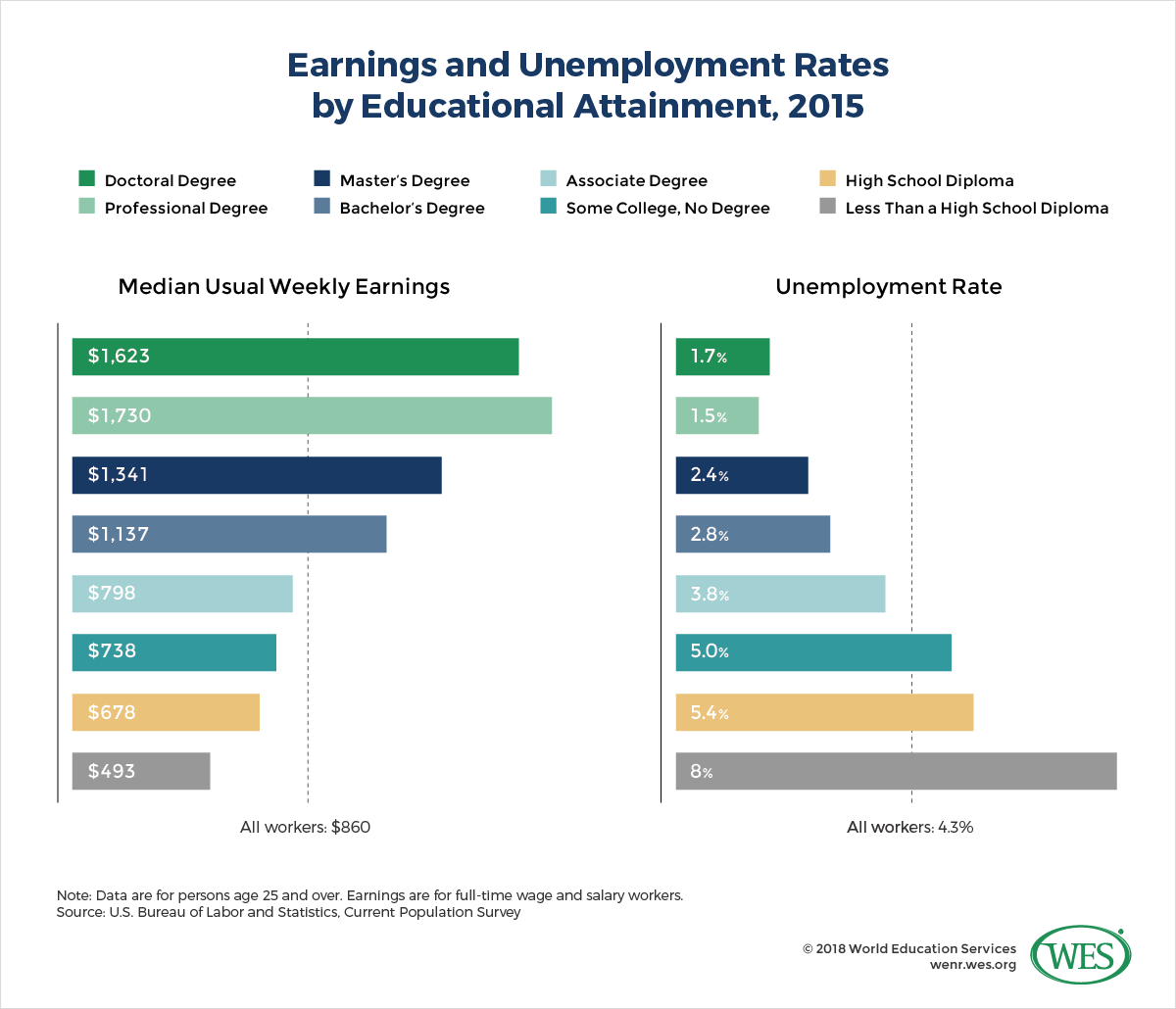

This attitude is borne out by the facts. Gaps between college graduates and high school graduates are substantial and have been widening [3] in recent years. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics [4] show that weekly median incomes among holders of a bachelor’s degree or higher were nearly twice those of high school graduates in 2014. Unemployment rates were also highest among those holding only a high school diploma or less. More recent studies found that in 2015 college graduates on average earned 56 percent [5] more than high school graduates.

Overall, the income-earning potential of high school graduates is low. Inflation-adjusted incomes among this demographic have been declining [3] for some time; and most job gains among high school graduates since the Great Recession of 2007–2009 have been in low-skilled service positions [5]. As Harvard Business School Professor of Management Practice Joseph B. Fuller says in a recent USA Today article [5], the U.S. has “a very limited vision of how to get people from their graduation in high school onto a path that’s going to lead them to have a successful, independent life.”

One option for improving the economic prospects of young adults outside of the university system is to strengthen training systems for mid-skilled vocational occupations—those that require some post-secondary education but less than a bachelor’s degree. Most individuals who presently take up apprenticeship training are older adults [5] seeking to upgrade their skills, while fewer students enter such vocational training programs directly after high school. In general, the number of participants in apprenticeship programs in the U.S. declined over the decade [6] 2003–2013, before beginning to increase [7] again in 2013.

The Trump administration recognizes the urgency of advancing vocational education in the United States. In June 2017, President Donald J. Trump signed an executive order [8] on “Expanding Apprenticeships in America” that seeks to increase the availability of such programs. The order notes that in

“…today’s rapidly changing economy, it is more important than ever to prepare workers to fill both existing and newly created jobs and to prepare workers for the jobs of the future. (…) Against this background, federally funded education and workforce development programs are not effectively serving American workers. Despite the billions of taxpayer dollars invested in these programs each year, many Americans are struggling to find full-time work. These Federal programs must do a better job matching unemployed American workers with open jobs, including the 350,000 manufacturing jobs currently available. Expanding apprenticeships and reforming ineffective education and workforce development programs will help address these issues, enabling more Americans to obtain relevant skills and high-paying jobs.”

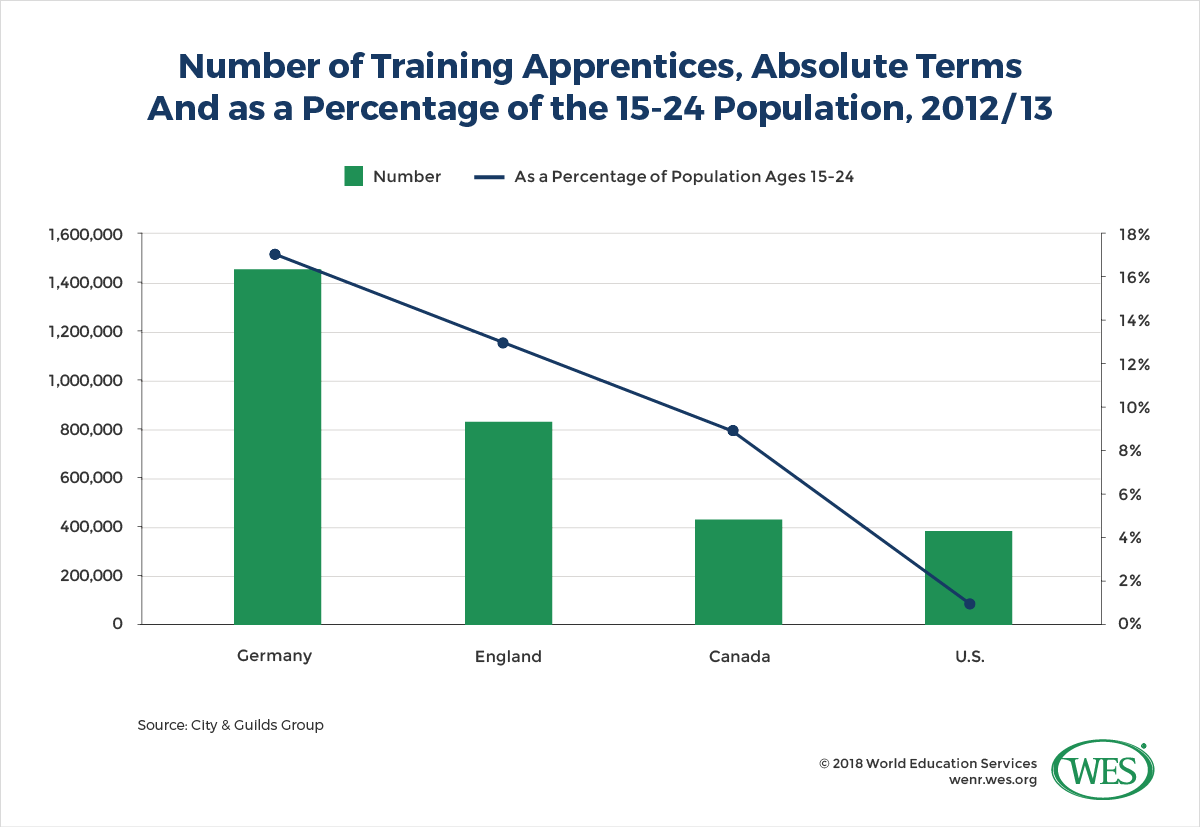

In contrast to the U.S., Germany has a highly effective work-based vocational training system that has won praise around the world. While university graduates in Germany also earn much higher salaries [10] than workers who have attained less education, vocational education and training (VET) in Germany is a very common pathway to gain skills and embark on successful careers: 47.2 percent—nearly half—of the German population held a formal vocational qualification in 2016. Fully 1.3 million students [11] in Germany enrolled in VET programs in 2017, compared with only 190,000 individuals [7] who registered for apprenticeship programs in the U.S. in the same year. Less than 5 percent [12] of young Americans currently train as apprentices, and most of them are in the construction sector.

Germany’s VET system yields tremendous economic benefits. For one, it helps to minimize youth unemployment: With an unemployment rate more than three percentage points below that of the U.S. (6.4 percent versus 9.5 percent in 2017, according to the World Bank [13]), Germany has one of the lowest youth unemployment [14] rates in the European Union.

In addition, Germany’s standing as a country with one of the most productive workforces [15] in the world is strongly aided by its VET system, which supplies Germany’s companies with well-trained employees. Germany’s dual training system, which combines practical training at a workplace with theoretical classroom instruction, also helps trainees transition into work life. VET opens up a variety of promising career options for young people, thereby strengthening society and culture.

The success of the German model has inspired countries like Spain, Greece, Portugal, Italy, Slovakia, and Latvia to adapt their own VET-like systems to the German model. Other countries, such as India, China, Russia, and Vietnam, are cooperating with the German government [16] to modernize their systems. Given Germany’s success and international recognition, could the VET system serve as a model for the U.S.? To address this question, we will briefly outline the structural differences in vocational education between the two countries before we discuss the prospects for as well as the obstacles to implementing a German-style VET system in the United States. The takeaway is that the U.S., although it has made some attempts to develop apprentice programs, is unlikely to adopt a formalized nationwide system as it exists in Germany.

A Brief Description of Germany’s VET System

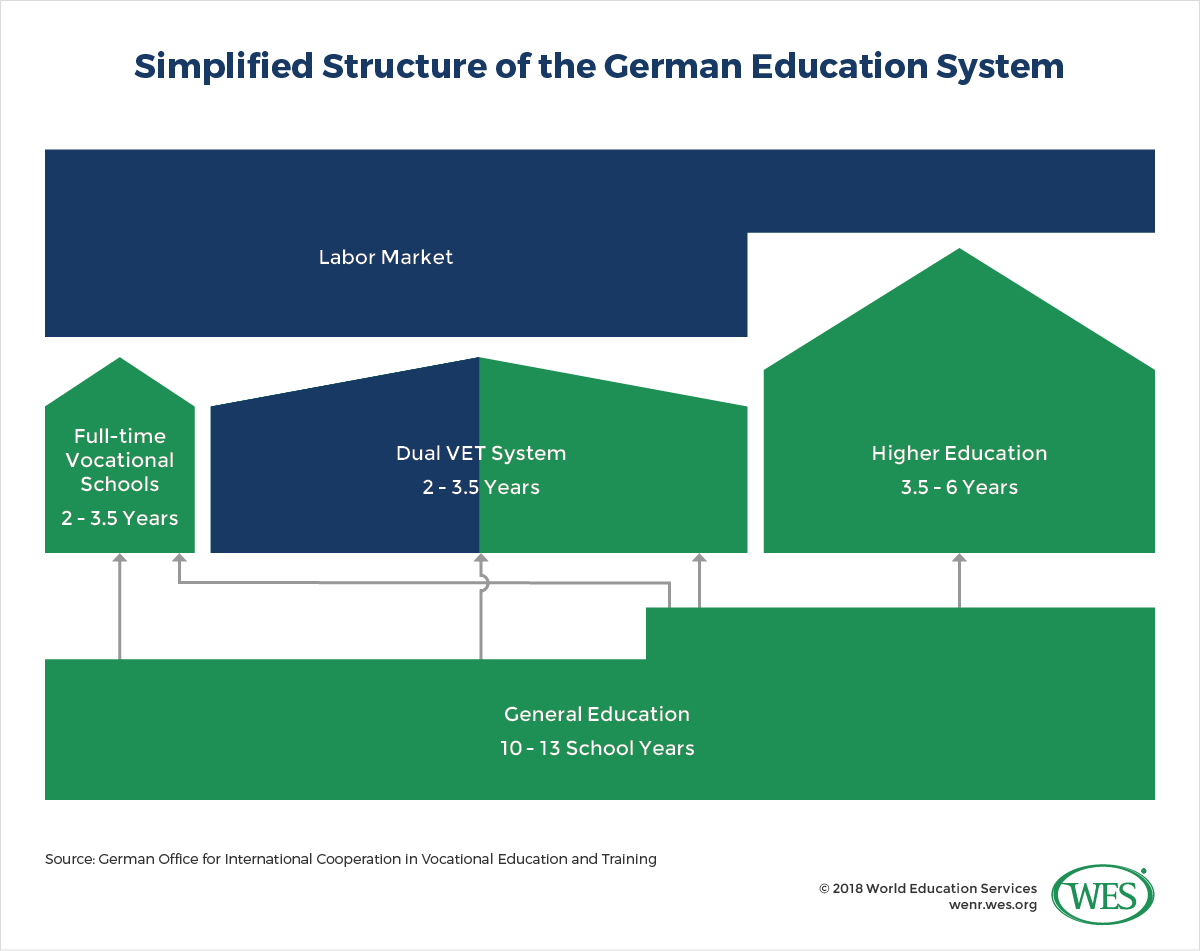

Despite being a federal country like the U.S., in which individual states have autonomy over educational matters, Germany has established a fairly uniform and highly regulated VET system nationwide. There are a number of different training programs in place, including full-time school programs that do not include a practical training component, but most vocational sector students enroll in the dual system (Duale Berufsausbildung). This system straddles upper-secondary and post-secondary education: Students typically enter vocational school (Berufsschule) after they complete lower-secondary education (ninth or tenth grade) and continue in vocational programs lasting two to four years, depending on the specialization.

During their studies, trainees spend three to four days a week [17] at a company to learn the practical foundations of their occupation. On the other one or two days, they study theoretical subjects in school. Alternatively, students may attend school in full-time blocks [17] of up to eight weeks in what are colloquially called sandwich programs. Participating companies are obligated to provide training in accordance with national regulations and pay students a modest salary.

VET is regulated and funded by both the federal government and the German states [18] and is closely coordinated with German industry. Employers and trade unions play an important role in decision-making processes and in the development of curricula and competency standards. School curricula [17] may vary slightly between the different German states (Bundesländer), but the final graduation examinations are uniform throughout the country and lead to formal vocational qualifications.

In their classes, students learn job-specific as well as general education subjects (German, politics, religion, physical education, etc.). Programs usually conclude with examinations administered either by the government or by industry associations like regional Chambers of Commerce or Chambers of Crafts. Graduates earn a state-examined or state-recognized vocational title (staatlich anerkannte Berufsbezeichnung) or a journeyman certificate, all of which are official certifications recognized throughout Germany. In 2015, there were officially recognized vocational occupations, ranging from carpenter to industrial electrician, tax specialist, dental technician, film and video editor, and product designer.

VET Programs in the United States

VET in the U.S., by comparison, is much less uniform and, as UNESCO puts it in its 2014 report, World TVET Database United States of America, is taught in non-parallel subsystems [20] that have limited articulation between them. Referred to broadly in the U.S. as career and technical education (CTE), vocational training is provided by high schools, career schools, and secondary and post-secondary technical schools, as well as by community colleges and universities. Private for-profit institutions dominate this sector, making up the majority [21] of CTE providers.

CTE is provided in various forms and includes elective vocational high school courses or programs at secondary-level career academies that combine college-preparatory curricula with career training. There are also so-called tech-prep programs, which are study courses that combine two or more years of secondary education with two years of post-secondary education. Students earn a certificate in a specific vocation [21] or an associate degree.

In addition, post-secondary non-degree certificate and diploma programs in vocational fields are offered by a multitude of career colleges. Apprenticeship programs may be offered by community colleges, where they are commonly tailored to students in associate degree programs, as well as by proprietary schools or trade unions, or informally by private companies. In 2017, approximately 533,000 trainees [7] were enrolled in apprenticeship programs formally registered with the federal government. These programs last a minimum of one year [22] and combine on-the-job training with theoretical education, usually in evening classes [21]. It is estimated, however, that most vocational and apprenticeship training takes place informally in private companies [23].

The U.S. Department of Education, a federal agency, also administers and coordinates CTE programs through its Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education [24]. Federal laws, including the current Technical Education Improvement Act [25] of 2006, seek to promote the integration of academic and vocational learning. In addition, a National Career Clusters Framework [26] has been developed with support from the government. It is intended to standardize career training by providing sample study programs and minimum competency skills in 79 career fields. They include architecture, construction, hospitality and tourism, agriculture, manufacturing, and finance.

Examples of Vocational Training, Licensing and Certification Modalities in the U.S.

Barbers, Hairstylists, and Cosmetologists are required in all U.S. states to be licensed. To obtain a license, candidates must complete state-approved programs, which are mostly offered by post-secondary vocational schools. Specific licensing requirements vary by state, but programs usually take between nine months and two years to complete [27]. They typically comprise a specified number of hours of classroom instruction and practical training (often between 1,500 and 1,800 [27] hours). Programs conclude with a non-degree certificate or other credential.

Automotive Service Technicians or Mechanics usually complete post-secondary programs that last between six months and one year [28] after high school and include a combination of classroom instruction and practical training. Alternatively, trainees may start as entry-level candidates (trainee technician, technician’s helper, or similar) and learn directly on the job.

Many employers require service technicians to be certified by the National Institute for Automotive Service Excellence (ASE). ASE offers several series of tests that lead to certification. For example, its Automobile and Light Truck Certifications [29] series certifies specific skills, such as repairing electrical and brake systems. Some employers require their technicians to earn a minimum number of certifications. Trainees who pass all required tests can become ASE-Certified Master Automobile Technician [30]s.

Associate degrees in automotive technology are also becoming increasingly popular and are often sponsored by automobile manufacturers and dealers. One such example is Toyota’s Technician Training & Education Network (T-TEN) [31], a partnership between Toyota, Lexus dealerships, and community colleges and vocational schools that places certified technicians in car dealerships across the country.

T-TEN offers several programs and certificate options, the two-year associate programs being the most common. Trainees typically alternate between on-campus study and practical training at a Toyota dealership in either quadrimesters [32] or blocks of eight weeks [33].

Plumbers represent a good and rare example of apprenticeship training in the U.S. Most plumbers learn their trade on the job in four- to five-year apprenticeship programs, not in a full-time technical school. Unions and businesses offer these apprenticeships, which usually involve about 2,000 hours of paid on-the-job training combined with classroom instruction.

Most states and employers require plumbers to be licensed, but licensing requirements vary by state; in some cases, even by city: A plumbing license in New York City [34], for example, might not be transferable to other cities within the state of New York.

Obstacles to the Establishment of a Standardized VET System in the U.S.

The limited transferability of plumbing licenses illustrates the highly decentralized and fragmented CTE landscape in the U.S. In addition, limited federal oversight and varying licensing requirements in different states effectively reduce labor mobility.

While the federal government has in recent years sought to expand CTE, there are few initiatives in place beyond the National Career Clusters Framework to standardize vocational education across the country. As noted above, the Trump administration strongly promotes the expansion of apprenticeship training. The Obama administration before it also supported CTE and in 2014 allocated USD $100 million [6] to apprenticeship programs in high-growth industries.

However, given the nature of the U.S. system of government, such initiatives usually take place within a strategic policy framework that seeks to “increase state and local flexibility [23] in providing services and activities designed to develop, implement, and improve” CTE. This is a fundamentally different approach compared with Germany’s highly regulated and standardized system.

It should also be noted that Germany’s VET is a more integrated and cooperative system with a long tradition of private sector buy-in. The German government subsidizes the theoretical or school component of VET by providing tuition-free education in public vocational schools, whereas CTE funding in the U.S. is much more limited. In the U.S., it is the companies involved rather than the government that are typically responsible for paying for the trainees’ education, making apprenticeship training a costly proposition for many companies. Supervisory and training requirements for apprentices are also higher than for regular employees.

Another problem is the high job turnover rate in the U.S., especially among younger workers. The main motivation for employers to have apprentices is to recruit future workers and train them to meet their company’s specific needs. The high turnover [35] rate among workers in the U.S. therefore tends to discourage employers from investing in trainees. While 82 percent of German employees [36] felt loyal to their employers in 2017, and 37 percent [37] of workers stayed with their company for more than seven years, U.S. workers remained with the same employer for a median average of only 4.2 years [35] in 2016. Notably, the employee retention rate in Germany is highest among workers holding a vocational qualification.

The lack of strong federal regulations and enforcement mechanisms in the U.S. also creates a “free rider” problem.2 [38] Unlike in Germany, where there is a collectively agreed-upon framework and VET is a long-standing tradition, individual companies in the U.S. are more likely to benefit from having access to a pool of skilled workers without participating in a training system.3 [39]

Resistance from labor unions further complicates the situation. Labor unions protect existing employees and therefore may perceive new training systems for young trainees as a potential threat to older workers.4 [40] The adoption of a nationwide CTE system could also threaten existing apprenticeship programs run by labor unions. Unions currently dominate apprenticeship programs in the construction industry [6], the sector that offers the greatest number of apprenticeship training programs.

In addition, apprenticeship training is hampered by the blue collar stigma often attached to it, particularly in the current national climate that prioritizes university education and emphasizes “college for all [41].” This stigma holds back many high school graduates from pursuing work-based CTE, even though graduates of apprenticeship programs have significantly higher income prospects. The City & Guilds Group, a British education and global skills organization, note [41]s in a recent case study that “nine years after enrollment, apprentices [in the U.S.] are estimated to earn $60,000 more than peers with a similar background who did not participate in an apprenticeship.” Recent data from the state of Montana’s registered apprenticeship program show that workers who completed the program earned USD $20,000 [42] more than the average salary in the state.

Despite all the obstacles, however, there are tremendous opportunities for CTE in the United States. High college dropout rates,5 [44] skill gaps,6 [45] and youth unemployment indicate the pressing need for an attractive, high-quality alternative to the traditional college pathway. U.S. President Barack Obama in his 2014 State of the Union address [46] emphasized the urgency to “train Americans with the skills employers need, and match them to good jobs that need to be filled right now. That means more on-the-job training, and more apprenticeships that set a young worker on an upward trajectory for life. It means connecting companies to community colleges that can help design training to fill their specific needs.”

Given the decentralized nature of the U.S. education system, however, CTE initiatives are unlikely to lead to a standardized nationwide system as it exists in Germany. While many countries seek to emulate it, Germany’s dual system is embedded in the country’s unique legal, historical, and cultural context and cannot be simply transferred one-to-one [47] to other countries.

As the German Bertelsmann Foundation has noted, Germany’s system can serve as a model for other countries, not a blueprint [16]: “Any country wishing to import a foreign system of vocational training must take existing … conditions into consideration and implement … vocational training in line with the country’s own educational, social, and economic objectives. Thus, the objective should be to prudently import adapted elements of another country’s system, but not an exact copy of it.”

In the U.S., this means that CTE initiatives will be pursued primarily at the state level. In recent years, a number of new work-based training systems have been developed in various states, some of them brought to fruition by German companies.

Current Dual Training Initiatives at the State Level

One such example is the dual training systems that the German companies BMW, Siemens, and Volkswagen imported to North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee to compensate for the lack of skilled workers in those states. The Volkswagen program was initiated in 2000, while the programs of Siemens and BMW were established in the late 2000s and early 2010s, respectively. Trainees in these programs receive supervised training at industrial plants, learning skills in areas like mechatronics, mechanical and electrical engineering, or computer software. Trainees study in tandem for associate degrees at local community colleges that have partnered with the companies.

The German companies’ financial investments are sizable: They usually pay salaries and tuition, or at least provide tuition assistance. Graduates typically continue their studies in bachelor’s programs while being employed at the companies. In Charlotte, South Carolina, alone, Siemens reportedly spends a total of USD $165,000 per trainee. (A detailed overview of these programs is provided by [48] the International Labour Organization.) The programs are supported by the state governments with measures like tax credits for apprenticeship sponsors; they have been so successful in fostering skills development and economic stimulation that other states like Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, and Ohio are exploring options to adopt similar apprenticeship programs.

Pathways in Technology Early College High School (P-TECH) is another example of a program similar to the German VET system. Co-sponsored by IBM, the Brooklyn, New York–based school prides itself on being the “first school in the nation that connects high school, college, and the world of work through college and industry partnerships [49].” Its unique program combines high school education with two years of post-secondary study and practical training at IBM. Students graduate with associate degrees in applied fields from the New York City College of Technology, a school in the City University of New York (CUNY) system.

Various schools nationwide have since adopted the P-TECH model, indicating that learning models that include practical, work-based components are becoming more attractive in the U.S., particularly in states that have large manufacturing industries. New Jersey, for instance, has established the MechaForce [50] initiative, a blended learning model loosely based on the German dual system, to train more skilled workers for its large manufacturing sector.

While driven by economic needs and shortages of skilled workers [51], such programs provide high school graduates as well as older workers displaced from low-skilled jobs a viable pathway to lucrative employment. If apprenticeship training and manufacturing jobs can overcome their blue collar stigma, there is tremendous growth potential for work-based training systems in many parts of the country. Over time, cultural shifts and changes in the U.S. economy could help to establish a respected nationwide vocational training system in the U.S.

1. [52] For most, a good job is primarily defined in terms of income. For instance, in its report Good Jobs that Pay without a BA, the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce defines a good job as one that pays at least $35,000 ($17 per hour) for adults under the age of 35 and $45,000 ($22 per hour) for workers older than 45.

2. [53] See: Kreysing, Matthias: Vocational education in the United States: reforms and results. In: European Journal of Vocational Training, no. 23, 2001, pp. 27-35, p. 33 www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/etv/Upload/Information…/232/23_en_kreysing.pdf [54] . The “free-rider problem” is a term used in social sciences that describes a situation in which, as Investopedia puts it [55], “…some individuals consume more than their fair share or pay less than their fair share of the cost of a shared resource. It is a market failure that occurs when people take advantage of being able to use a common resource, or collective good, without paying for it, as is the case when citizens of a country utilize public goods without paying their fair share in taxes.”

3. [56] Ibid.

4. [57] Ibid.

5. [58] The most recent National Student Clearinghouse Research Center’s Signature Report [59] indicates an overall completion rate of 56.9 percent for degree-seeking students who started college for the first time in the fall of 2011. Only 37.5 percent of students at public two-year colleges complete their studies.

6. [60] The career and technical student organization SkillsUSA predicts a shortage of 10 million skilled workers [61] by 2020.