Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Online education is a divisive topic. Often criticized as an inferior form of education providing an isolated learning experience at best, or as a harbinger of global, Western-dominated educational homogenization at worst, online education is simultaneously considered a promising means to increase access to education in developing countries.

Current trends in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia illustrate that online education is gaining traction in these regions despite persistent technological barriers—not because it is a better form of learning, but because it is perceived as a rational, cost-effective means to widen educational opportunities. Escalating population growth and exploding demand for education are causing countries like India to increasingly embrace online education. While still embryonic, digital forms of education will likely eventually be pursued in the same vein as traditional distance learning models and the privatization of education, both of which have helped increase access to education despite concerns over educational quality and social equality.

Introduction

Education systems in sub-Saharan Africa and other developing regions are in crisis. To mention just one of many problems, UNESCO estimates [1] that one in five children worldwide did not participate in any form of education in 2016. Almost all of these 263 million children—6 to 17 years of age—lived in developing countries. Yet, this crisis could get even worse. Africa’s youth population is expected to double to 830 million [2] people by 2050, but few resources are dedicated to educating these young people.

Against this backdrop, online education is getting increased attention as a possible solution to widen access to education at an affordable cost. Bill Gates, co-founder of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and principal founder of Microsoft, for instance, believes that online learning will revolutionize education in the developing world and help close global literacy gaps [3].

In fact, distance education already plays a crucial role in providing access to education for millions of people in the developing world. Open distance education universities in Bangladesh, India, Iran, Pakistan, South Africa and Turkey alone currently enroll more than 7 million students combined. Many of these mass providers are increasingly going digital, while more recent forms of e-learning like massive open online courses (MOOCs) are also proliferating.

In many developing regions, participation in online education is still constrained by technological infrastructure barriers, commonly called the digital divide. However, the rapid spread of smartphones has turned digital learning into a much more viable proposition in recent years. Mobile broadband technology is quickly penetrating even remote rural regions, providing Internet access to the people that live there.

Cash-strapped governments in low-income countries are thus increasingly looking to online education as an option to bridge capacity gaps. Compared to building ever-more brick-and-mortar institutions, digital learning promises a cheaper and more instantaneous remedy. Whether or not online education can live up to this promise remains to be seen. However, the growth potential for online education in developing countries is certainly enormous. Some observers consider Africa “the most dynamic e-learning market on the planet [4].”

This article describes trends in distance and online higher education in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and the Indian subcontinent in the context of global growth in digital learning. To grasp the sheer magnitude of the learning crisis in these regions and to understand why online education could be so revolutionary, we will first outline mounting demographic pressures and capacity problems, as well as upsurges in privatization and open and distance learning (ODL). We will then describe the current spread of digital education and technological advances in SSA and South Asia, and discuss online education as a means of expanding capacity.

The takeaway is that distance education and digital learning will continue to expand quickly in SSA and the Indian subcontinent. Digital education models are unlikely to substitute for traditional research universities or form the bedrock of world class education systems. However, online education will play an important supplementary role similar to the role distance learning universities have already played for decades.

The objective of mass-scale distance education in countries like India is not the cultivation of academic elites, but the cost-effective delivery of education to deprived populations. Online education, similarly, could provide learning opportunities for tens of millions of people and throw disadvantaged countries a lifeline in their quest to broaden access to education. In light of the exploding demand, every ounce of capacity counts.

The Spread of Digital Education

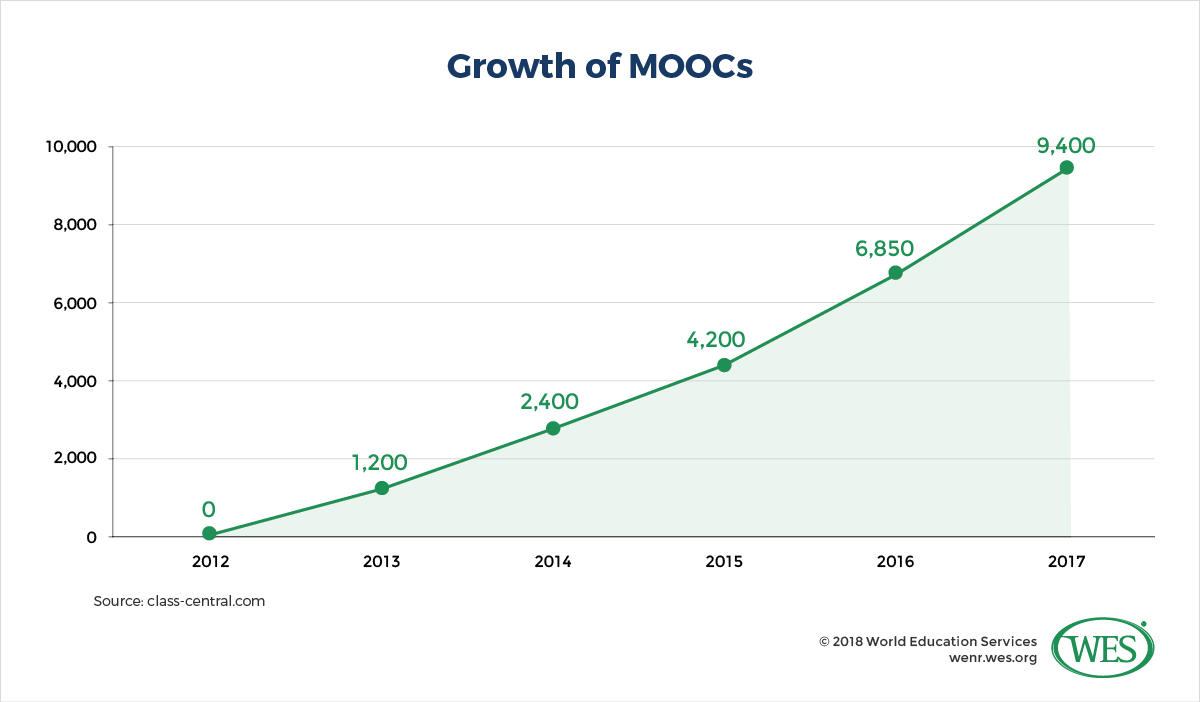

Digital education is flourishing. The number of MOOCs, for example, has skyrocketed since they first appeared in the 2000s. MOOCs are now mainstream, and the number of available courses was reported in 2016 to be growing daily [5].

The New York Times declared 2012 “the year of the MOOC [6]”—an acronym that was, at the time, still an unfamiliar term. Since then, the number of MOOCs has increased by more than 683 percent: According to Class Central [7], a MOOC listings provider, there are now 9,400 courses on offer worldwide compared with only 1,200 MOOCs in 2013 [8], while the total number of learners enrolled in MOOCs has shot up to 81 million from 10 million. Most MOOCs are offered directly by private providers like Coursera or edX, but the number of universities offering MOOCs has also increased from 200 to 800.

As the e-learning market evolves, it is also becoming increasingly complex and diversified. Current offerings are trending toward audited short-term certificates (so-called micro-credentials or nano degrees), as well as “stackable” degree programs [10] in which learners earn an academic credential by completing a self-paced sequence of MOOC certificates that can later be applied toward a degree.

However, more traditionally structured online programs are booming as well. In the United States, it is now commonplace for established universities to offer online degree programs. Fully 6.36 million higher education students (31.6 percent of all college students) took at least one online course in 2016 [11]. About half of these students studied exclusively online. In addition, U.S. companies are increasingly using [12] e-learning to train their employees [13].

Most market researchers expect the global e-learning market to grow at brisk annual rates anywhere between 7 percent and 10 percent [14] over the coming years. In a recent report [15], Research and Markets projects that the global market volume will increase from USD$159.5 billion in 2017 to USD$286.6 billion in 2023, while other researchers [16] predict that the e-learning market will reach USD$331 billion by 2025.

A Glossary of Terms

Over the past years, many different terms have been coined for learning and teaching that takes place primarily over the Internet. Students access course materials or class lectures on mobile phones, tablets, and—less often in developing regions—on laptops or computers. While students in some cases access digital learning materials on pre-loaded laptops or mobile devices while simultaneously attending classes at a school, most of this type of education is delivered remotely over the Internet. Terms used largely synonymously include digital learning, digital education, online education, and electronic learning or e-learning. “M-learning” specifically refers to education delivered via mobile phones.

Blended learning usually refers to remote learning programs that are supplemented with traditional in-person lectures, classes, or study groups, as well as access to physical educational resources such as libraries. Many experts consider the blended or hybrid approach the most effective model of remote learning.

Distance learning or distance education generically refers to any kind of remote learning, but it also has a specific meaning and history that started long before the Internet revolution. These terms often refer to structured programs offered remotely to students. They started originally as correspondence courses; many are now delivered completely or primarily online.

The terms “open” and “open-access” providers refer to higher education institutions that accept all or most students who have earned a high school credential or its equivalent. Not all open institutions offer distance learning; and not all distance learning programs are open.

MOOCs (massive open online courses) are called “massive” and “open” because they typically don’t have formal admission requirements and can be attended by thousands of students at the same time. While many of these courses were initially free of charge, they are now becoming increasingly monetized. Initially offered by private U.S. providers like Coursera or edX , they are now frequently licensed to higher education institutions, some of which have also begun to develop their own MOOCs.

Digital learning is still predominantly used in industrialized countries. Most students enrolled in MOOCs, for instance, are postgraduate students in high-income countries [17] seeking to upgrade their skills. Overseas students enrolled in online courses offered by U.S. universities made up only 0.7 percent [11] in 2016.

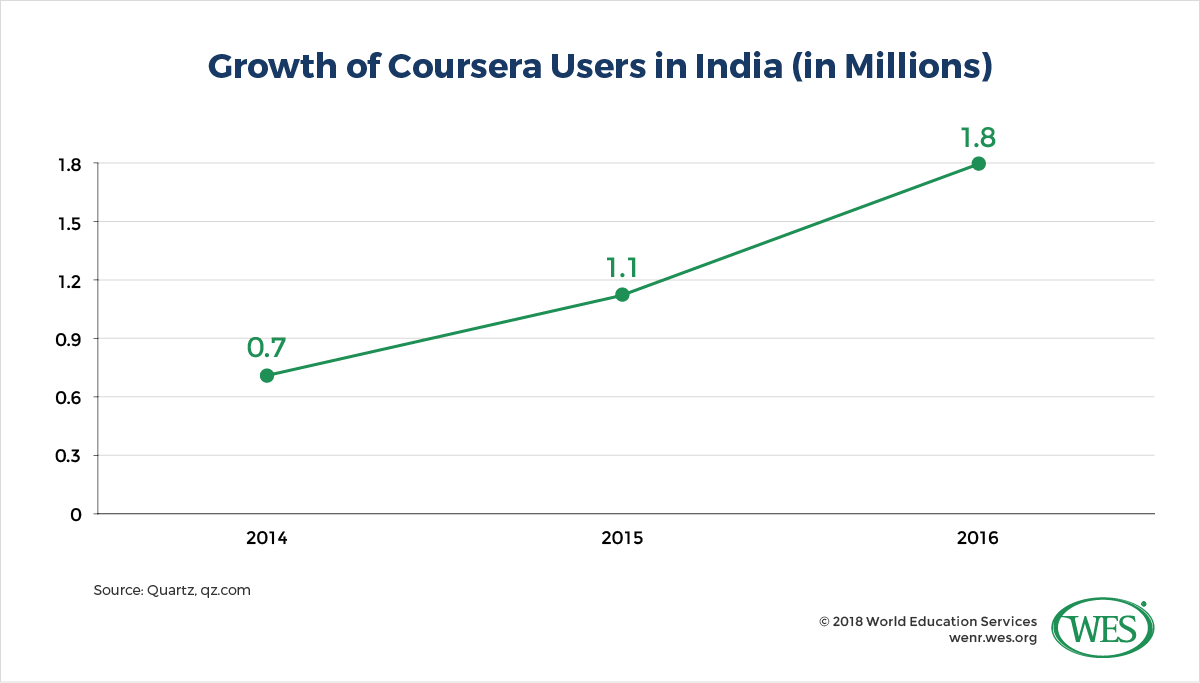

That said, developing countries are catching up fast—despite the fact that courses offered by U.S. providers like Coursera or Udacity are getting increasingly expensive [18].1 [19] India quickly became Coursera’s second largest user market [20] (after the U.S.). The number of Indians enrolled in Coursera MOOCs jumped by 70 percent [21] between 2015 and 2016 alone. By 2017, Coursera’s Indian user base had reached 2 million [22], making up about 7.7 percent of all enrollments worldwide.

The number of students from developing nations enrolling in online degree programs in industrialized countries is also growing. Between 2011 and 2015/16, the number of South African students enrolled in U.K. online degree programs, for instance, increased by 135 percent [23]. Despite rising costs for online programs, earning a degree online is still cheaper than studying overseas. The number of Nigerian students in online degree programs based in the United Kingdom is sizable: 5,252 [24] in 2015/16.

These developments suggest a growing demand for products like online degrees and MOOCs. In all probability, local institutions in developing countries will, over time, increasingly compete with Western providers over absorbing this demand. The e-learning landscape in developing countries is set to evolve dramatically as local private providers, public universities, and governments all push into this dynamic market segment.

Digital learning in regions like SSA and South Asia is embryonic and bound to accelerate. At a time when the industrialized world has entered what scholars call a post-massification era,2 [25] the growth potential for all forms of education is still gargantuan in these regions. While Europe and North America achieved an average tertiary gross enrollment ratio (GER) of 75 percent [26] in 2015, tertiary GERs in South Asia and SSA stood at only 25 percent and 8 percent.

What makes online education increasingly attractive in SSA and South Asia is the fact that many countries there cannot follow traditional approaches to massification. These regions face nearly insurmountable challenges to achieving participation rates anywhere near those found in Europe and North America.

“Youth Bombs”: The Challenge of Rapid Population Growth

Crucially, population growth in these regions will generate a crushing demand for education. As industrialized countries in Europe and East Asia are aging [27], the population of Africa alone is expected to double by 2050 [28]. By 2030, cities like Lagos and Kinshasa are projected to have more than 20 million [29] inhabitants, most of them youngsters. Fully 40 percent of the population on the African continent is now under the age of 15, and the youth population (15- to 24-year-olds) is expected to increase even further—by 42 percent [30] by 2030.

Demographic projections at the country level are stunning: Nigeria’s population will double to about 400 million by 2050, turning the West African country into the third largest nation on earth. In neighboring Niger the youth population is projected to increase by 92 percent [30] between 2015 and 2030 alone. The country was said to gain about 800,000 people annually until 2016. If its birth rates don’t decline, Niger’s population could possibly mushroom to 960 million people [31] by 2100 (compared with 22.3 million today).

India, meanwhile, will within the next seven years surpass China as the largest nation on earth and grow to about 1.5 billion [28] people by 2030 (up from 1.34 billion in 2017). No other country today has a total youth population greater than India’s: 600 million people [32] in the country are under the age of 25.

The situation in other South Asian countries is similar. Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan are currently experiencing a “youth bulge.” Pakistan now has the highest percentage of young people ever recorded in its history [33]—64 percent of the population is below the age of 30. By 2050, Karachi is projected to become the third largest city in the world with 31.7 million [34] people.

In the long term, these demographic trends could be beneficial. Economists often consider youth bulging a positive phenomenon, a demographic dividend rewarding countries with a young labor force and opportunities for development. But the demographic dividend is not simply a demographic gift. Turning youth bulging into economic growth requires that countries educate their growing youth cohorts and provide them with employment opportunities.

Countries in SSA and South Asia are struggling to do just that. The youth unemployment rate in SSA stands at 14.2 percent [35], while Nepali youth deem prospects for employment so dire that not less than 28 percent [36] of the country’s labor force is employed abroad. In India, hundreds of thousands of labor migrants leave the country each year [37].

Growing Middle Classes Will Increase Pressures on Education Systems

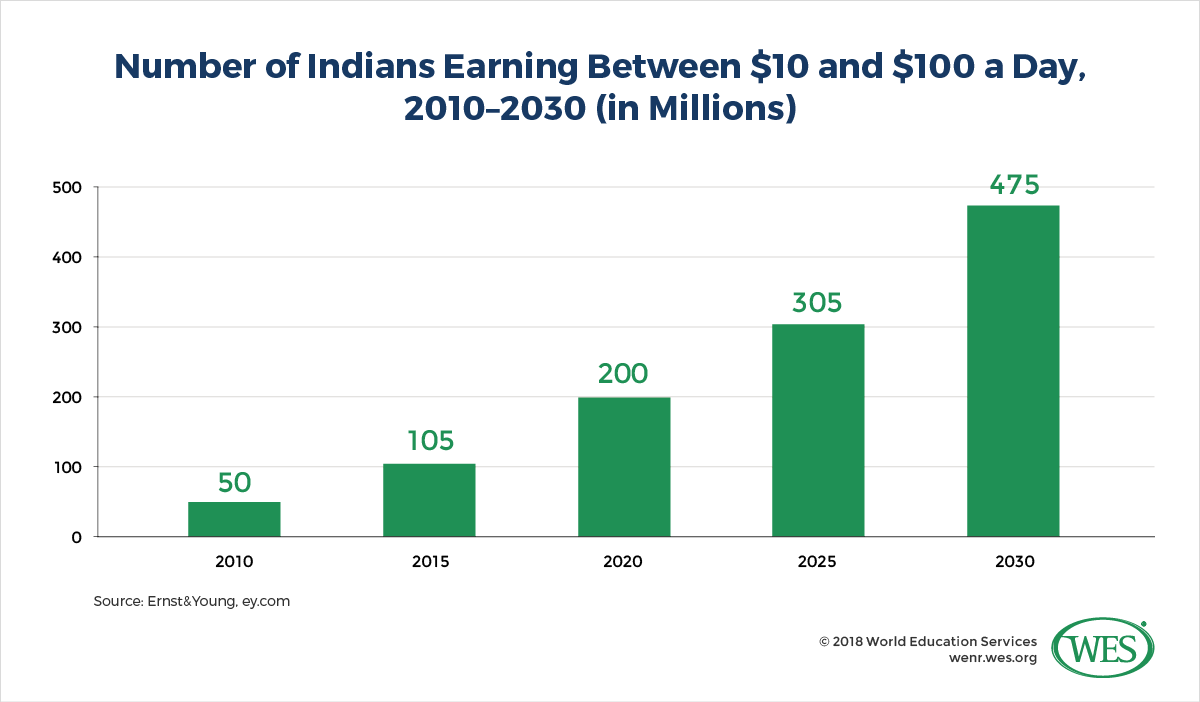

The demand for education won’t be curbed by economic growth. Perhaps more so than sheer population growth per se, it will be increased prosperity and the concomitant purchasing power of middle classes that will drive the demand for education. India’s economy is growing fast [38], and the size of its middle class is expanding at high velocity. The number of people in middle income brackets is expected [39] to increase almost 10-fold within two decades, from 50 million people in 2010 to 475 million people in 2030. Some analysts predict that the country will become the world’s second largest economy by 2050 [40]. In Bangladesh, meanwhile, an estimated 30 million to 40 million people will join the ranks of the middle class by 2025 [41].

These are statistics to watch, as they could be transformative. In China, rising incomes fueled a drastic increase in education participation [42]. Over the last two decades, the number of Chinese university graduates grew 10-fold [43], while China’s education system became the world’s largest [44] with 43.9 million tertiary students in 2016 [45]. If South Asia follows China’s example, demand for education in the region will shatter ceilings.

In Africa, wealth accumulation happens on a smaller scale, but the middle class is growing nonetheless, notably in the continent’s fast-sprawling cities. One recent study by the consulting firm EIU Canback, a sister company of the Economist magazine, estimated that Africa’s middle class had grown modestly from 4.4 percent in 2004 to 6.2 percent in 2014 [47].3 [48] At any rate, the sheer number of upcoming youngsters in Africa will likely weigh down the hopes they have of attaining their educational aspirations—and those of their countries’ leaders for them.

How Many More? The Limits of Building Brick-and-Mortar Institutions in India

Youth bulging makes it increasingly difficult for SSA and South Asian countries to address capacity shortages by building or expanding universities. Over the past two decades, India has already created capacity for a gargantuan 30 million students. The tertiary student population increased sixfold, from 5.7 million in 1996 to an estimated 36.6 million [49] in 2017/18. The number of universities, likewise, grew from 190 [50] in 1990/91 to 903 in 2017/18 [49], while the number of colleges literally exploded: 18,000 new colleges [51] were established between 2008 and 2016 alone—that’s more than six new colleges per day.

Despite this massive expansion, supply in India keeps trailing demand. The country is expected to soon harbor the largest tertiary-age population in the world while still having a higher education GER of only 25.8 percent [49] (2017/18). The government seeks to increase the GER to 30 percent by 2020—an objective that would require adding more than 4 million additional university seats within the next two years.4 [52] Recent studies estimate that an additional 700 universities [53] and 35,000 colleges will need to be built to keep up with demographic trends.

Even if India’s mushrooming private sector could absorb much of this exploding demand, India is ill-equipped to handle an expansion of this scale: Education spending currently stands at less than 3 percent of GDP [54] nationwide (below levels of 2012/13), and generating additional funds will not be easy. Insufficient capacity is just one of the Indian education system’s many problems, which range from teacher shortages [55] to quality problems and abysmal unemployment rates [56] among university graduates.

To sum up, the Indian system is severely overburdened. As the British Council has noted [57], “… the change coming to South Asia cannot be embraced by expanding an existing system, it demands a new approach to the academic model, to quality, and to funding. Failure to find new solutions and to meet the demographic demand for high quality accessible education will see the region locked into a spiral of low value skills and even higher graduate unemployment.”

Academic Exclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa

The situation in SSA is even worse. While enrollment rates have gone up over the decades, a majority of Africans remain excluded from higher education. According to a recent World Bank study [58], the “increasing demand and limited supply of tertiary education in the SSA region has led to tertiary education being available only to a subset of the youth population. … To date, tertiary education in SSA region has remained elitist, benefiting students mostly from the most affluent, well-connected families… [T]ertiary education in the region is not equitably producing the human capital that the countries direly need.”

This crisis comes amid the construction of ever more higher education institutions (HEIs). Between 1990 and 2014, the number of public universities in SSA grew from 100 to 500, while the number of private HEIs skyrocketed from 30 to more than 1,000 [59]. In Kenya, a country that had only four universities in 1989 [60], the number of universities recently more than doubled within just six years, from 33 in 2012 to 73 today [61].

That said, Nigeria could possibly top that expansion soon. The country’s National University Commission is currently processing accreditation applications from 292 new institutions [62], a development that could nearly triple the number of Nigerian HEIs. In another example, Ethiopia reportedly had only two public universities and six colleges that in total had capacity to enroll 10,000 students in 1991 [63]. By 2014/15, the country had 36 public HEIs, while the number of private institutions jumped from zero to more than 100 [64].

These new universities have greatly expanded access, but they are—all together—but a drop in the bucket, given the mounting demand. In 2014, there was just one HEI for about 652,000 people in SSA. Compare that with the U.S., which has one accredited degree-granting institution per 67,435 people.5 [65] In nations like Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, this ratio is as high as one university for 1.2 million people, more than half of whom are below the age of 30.

Present capacity shortages in Nigeria are so severe that less than 40 percent [66] of university applicants gain admission, effectively locking out one million aspiring students each year. In light of such need, Kevin Andrews, vice chancellor of the pan-African UNICAF University, noted in a recent interview [67] with Times Higher Education that “Africa would need to build 10 universities a week, [with] each [one enrolling] 10,000 students every week for the next 12 years” in order to keep up with demand.

Even if that were possible, constructing ever-more universities is of limited use if governments cannot adequately fund them. Many education systems in the region are already chronically underfunded—a situation that will only worsen as systems expand and become increasingly expensive to manage. More than half of Kenya’s public universities, for instance, are presently insolvent as the government is cutting funding [68] on various fronts. Funding problems are omnipresent in SSA, despite the fact that governments spend relatively large parts of their budget on education by international comparison. The average public debt as a share of GDP in SSA has increased by about 15 percent between 2011 and 2017, according to the IMF [69].

The Solution of Privatization: A Panacea for Expanding Access?

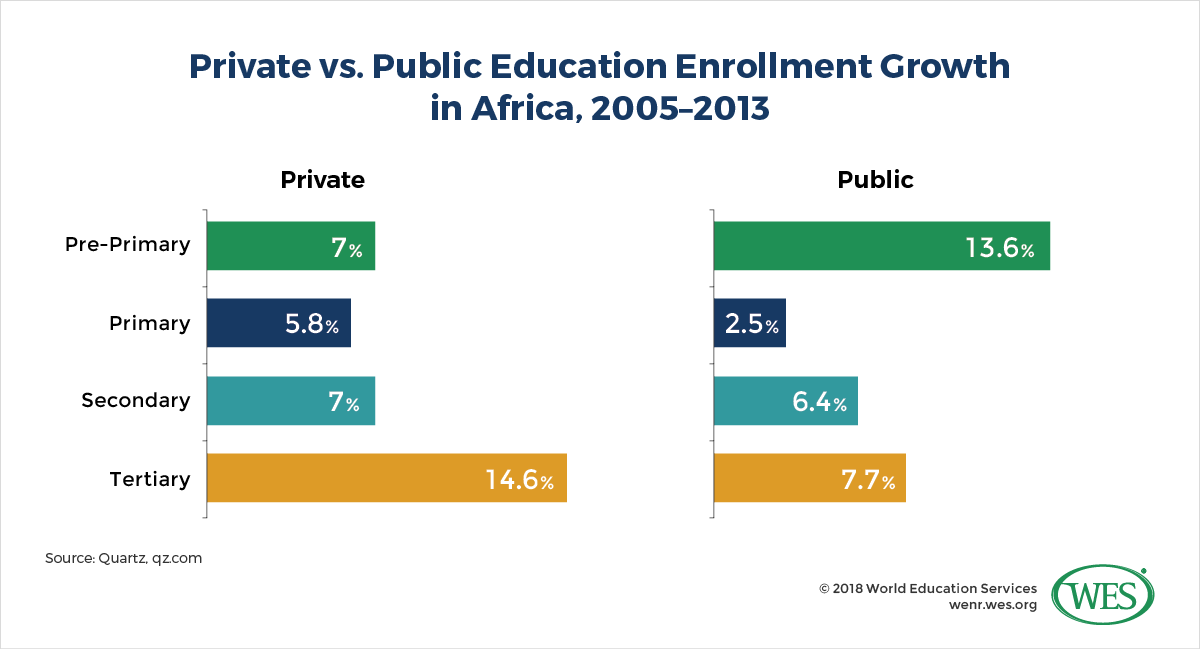

Given such resource shortages, it is unsurprising that a rapid privatization is underway in many education systems. Privatization affords governments an opportunity to appease popular demand for education while externalizing the costs. While unfettered privatization is not a reality across all developing countries, tertiary private sector enrollments in Africa, for instance, have grown twice as fast [70] as public enrollments between 2008 and 2013. One in four African students is expected [71] to study at a private school by 2021 (at all levels of education, compared with 21 percent today ).

This trend is well described in UNESCO’s current Global Education Monitoring Report, which notes [26] that “the share of private institutions in tertiary enrolment is growing rapidly in low- and middle-income countries. In Nepal, it grew by 38 percentage points between 2000 and 2015, followed closely by Burundi and Rwanda, where private institutions now account for two in three students. In Congo, one in three students attended a private university or college in 2015, up from close to zero in 2000.”

Developments in India are similar: The number of private universities has in recent years grown at an estimated rate of 40 percent [72] annually. In 2014, the private sector accounted for 64 percent [72] of institutions and 59 percent of all tertiary enrollments.

Private education can play a crucial role in increasing access. Low-cost private elementary schools, for example, help educate millions of children in Africa and South Asia, often in the most marginalized neighborhoods [74]. In Lagos alone, more than 18,000 low-cost private schools have sprung up since 2010, drastically boosting capacity in a city that previously had only 1,600 public schools [75]. Private HEIs, meanwhile, often have lower admission standards than those of competitive state universities, enabling students locked out of the public system to attend university.

Beyond absorbing demand, well-managed private institutions may provide better education more geared toward employment than that of cash-strapped public institutions. Private schools also tend to be more responsive to industry needs and can act as agents of change. As African academics Wondwosen Tamrat and Damtew Teferra have emphasized [76], “[private] universities infuse competitiveness due to their dynamic and entrepreneurial features. In 1990, South Africa had only five MBA programs offered by public providers serving around 1,000 students, but because of competition from private institutions, the number of providers grew to 40 and MBA enrollment to 15,000 within a decade.”

At the same time, many private HEIs in developing regions are small niche providers that can neither compete with big public institutions nor absorb large numbers of students. Privatization has also led to a mushrooming of low-quality for-profit institutions and unlicensed providers that deliver substandard education and award credentials of little value.

In some countries, this situation has spiraled so far out of control that governments now increasingly police the spread of such fly-by-night providers. In India, for instance, thousands of these small, private “mushroom schools” that had sprung up all over the country have been shut down since 2009 [77].

Quality audits and school closures are becoming increasingly common in Africa as well. In one recent example, in 2017 Zimbabwe shut down 280 private colleges [78]. However, many African governments struggle to keep up with the wave of private “teaching shops” flooding their countries. Rigorous quality control mechanisms will be needed to keep this ballooning private sector under control and protect students from substandard, predatory providers.

There are also valid concerns that private education worsen [79]s the exclusion of poorer social segments and widens disparities in access to education. A recent World Bank study [59], for instance, has shown that private-led growth in several African countries disproportionally benefited wealthier households and reinforced social inequalities.

Despite such problems, private education will inevitably continue to thrive, since governments don’t have the capacity to cope with exploding demand. And privatization can certainly help mitigate capacity gaps and advance quality in education systems, as long as it is implemented under adequate oversight.

The British Council recommends [57] that governments in South Asia cultivate “… a cohort of credible private-sector universities renowned for excellence, with targeted funding and scholarships to facilitate access[.This] has proven a successful strategy elsewhere in Asia and in South Asia [and] … will need to take place in tandem with efforts to improve regulation and quality assurance in the private sector.”

Open Distance Learning: An Effective Way to Absorb Demand

Next to privatization, distance education has been pursued as a means of expanding access for quite some time. In fact, distance education existed long before the Internet revolution. Since the 19th century, universities in the U.S. and Britain offered distance education in the form of correspondence courses.

In tandem with technological progress, distance learning began to incorporate radio broadcasts, TV programs, and audio- and videocassettes. In 1953 [80], the University of Houston in Texas was the first university to televise course materials. Britain’s Open University then took this concept to larger audiences when in 1971 it started to broadcast teaching materials [81] on the BBC. It is now the largest university in Western Europe with 173,927 students [82] (2016/17), most of whom attend remotely.

India’s IGNOU: The Largest University in the World

The model of the Open University has been emulated with great success in developing countries, giving rise to several mega universities. India was among the early adopters when in 1985 it established the Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU). Dubbed “the People’s University,” IGNOU is designed to provide “higher education to a large cross section of people, in particular the disadvantaged segments of society [83].”

While IGNOU may not feature in global university rankings, it needs to be regarded as one of the world’s most important HEIs because of its sheer size. IGNOU’s student population today exceeds three million [84], having shot up from 4,528 in 1987, making it the largest university on the globe by most accounts, although the Open University of China may now be even larger.6 [85]

IGNOU inspired the creation of other open universities in many Indian states, and led to the establishment of a Distance Education Council (DEC) that it oversaw. The DEC provided quality assurance [86] for distance education nationwide until that function was transferred to a newly established Distance Education Bureau [87] in 2013.

Distance education has played an important role in absorbing demand in India and currently accounts for 11.45 percent [88] of higher education enrollments. Many of India’s traditional universities now offer distance education programs. The total number of institutions offering distance learning programs increased from one in 1962 to 256 in 2010 [89].

IGNOU delivers education by “providing print materials, [audio- and videotapes], broadcast on radio and … TV channels, teleconferencing, video conferencing [and] also … face to face counseling, at its study centers [83].” Since 2000 [90], the institution is increasingly using the Internet to distribute teaching materials [91].

Technological advances have increased the speed and ease of distance teaching and fueled IGNOU’s ambitions to establish itself as a global virtual university. Notably, the Indian government’s 2004 launch of the world’s first satellite dedicated exclusively to distance education (EduSat [92]) has greatly expanded IGNOU’s capacity to deliver digital content. However, IGNOU still maintains a hybrid learning model that enables students to receive tutoring at nearly 3,000 [93] learner support centers throughout India and at 12 centers [94] overseas.

Mega-Universities in Other Countries

Growing demand has fueled similar developments in other countries. Iran, for example, underwent a youth bulge phase over the past two decades that doubled the population between 1980 and 2016. The effects were the same as in SSA and South Asia today: exploding demand, insufficient capacity, more HEIs, and a mushrooming private sector. One answer to this crisis was the establishment of Payam-e-Nour University [95] (PNU), an institution that is now the largest distance education provider in the country with more than 940,000 students [96].

PNU has proved effective in absorbing demand, despite sometimes being criticized for delivering low-quality education [97]. Under the motto “education for all, anywhere and anytime,” PNU has helped to increase enrollment rates even in Iran’s most remote regions. PNU offers traditional distance education programs, hybrid (blended) programs that include optional in-class tutoring, and—since 2006—e-learning programs offered exclusively online. According to PNU’s website [98], the number of enrollments in pure online programs, however, is still small at fewer than 10,000 students.

These are several examples that illustrate that government-sponsored open and distance learning (ODL) is growing in size and scope in various countries. In Pakistan, the Allama Iqbal Open University [99], a public ODL provider designed to “provide education and training to people who cannot leave their homes and jobs for full-time studies,” is now the largest university in the country with an average annual enrollment of 1.2 million students. The University of South Africa (UNISA), the country’s main ODL provider, enrolls one-third of South Africa’s students; it is the largest university in all of Africa with 400,000 students [100]. Its most famous graduate is Nelson Mandela, who earned a UNISA correspondence degree [101] while imprisoned.

In another example, the National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN) is Nigeria’s largest university with 254,000 students [102] and 77 study centers (2017). NOUN recently established the first digital online Open Educational Resources repository in West Africa [103] and began offering MOOCs. In 2016, the university announced that it would distribute i-NOUN tablets [104] pre-loaded with study materials to all its students.

In Turkey, distance education has contributed strongly to boosting tertiary GERs from 30 percent in 2004 to 86 percent in 2014. Anadolu University, Turkey’s national ODL provider, has grown into a veritable mega-university. It enrolled more than 1.7 million [105] undergraduate students in 2014 (about one-third of all of Turkey’s higher education students).

The Utility of Open Distance Learning

ODL universities provide inclusive, needs-based education. They are generally considered an effective instrument of social development and have been supported by organizations like UNESCO. What most have in common are their relatively low admission standards compared to other HEIs. Most, but not all, charge tuition for their programs, which range from short-term diploma and certificate courses to full-fledged bachelor, master, and doctoral programs.

Many ODL institutions follow a blended learning model that combines various forms of distance delivery with tutoring at study centers, which also provide students with access to libraries, computers, and videoconferencing facilities. Flexible schedules allow first-time students and working adults alike to pursue education, even in remote underserved regions.

ODL is often dismissed as substandard; however, open universities were not conceptualized to function as centers of academic excellence. They were designed to bring education to the masses at low operating costs. IGNOU, for example, educates its more than three million students with a lean staff of only 573 faculty members and about 50,000 academic counselors [93]. ODL is not a solution for creating world-class education systems, but it plays a vital role in providing access to millions of students and has become an integral part of many education systems.

It must be acknowledged, however, that in general the quality of distance education providers varies greatly. The proliferation of substandard programs under the purview of IGNOU’s DEC, for example, has created quality problems in India akin to those the country experienced after the rapid growth of private brick-and-mortar HEIs. As a result, India’s University Grants Commission (UGC) increasingly clashed with IGNOU [106], closed several distance providers, and banned distance education [107] at non-university institutions (and deemed-to-be universities [108]) after shifting quality assurance to the UGC’s Distance Education Bureau.

But it would be a mistake to dismiss all ODL institutions as low quality. Britain’s Open University, for instance, is ranked among the world’s top 500 universities in the current Times Higher Education world university ranking [109]; and UNISA is considered one of the better universities in South Africa (it is currently ranked at position 801 to 1000 in the Times ranking).

As pioneers in distance education, many ODL universities now increasingly deliver learning content via the Internet. However, the status of ODL mega-universities as the main providers of distance education is increasingly in jeopardy because of digital education initiatives pursued by other HEIs. “Many Open Universities are experiencing [a] severe competitive threat from other local universities or from foreign entrants who are taking advantage of new technologies to move quickly, sometimes more quickly than Open Universities can, into the online space [110] ….” says the Open University’s Alan Tait.

Digital Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: Current Trends and Growth Potential

While ODL mega universities still dominate distance education, newer forms of remote learning like MOOCs and new online universities are spreading increasingly in regions like SSA. For instance, in 2017, the Association of African Universities (AAU) inked an agreement with the upcoming online education provider eLearnAfrica [111]. The deal is expected to expand the online course offerings of AAU’s 380 member universities by 1,000 MOOCs [112], making learning opportunities possible for an additional 10 million African students.

AAU’s secretary general, Etienne Ehouan Ehil, has noted that “challenges of limited access to quality higher education continue to haunt us. Therefore, building capacities of African universities to be innovative in their … learning methods for increased access to quality higher education is top priority for the AAU. This partnership with eLearnAfrica will help us achieve this goal [113].”

This development reflects the recent growth of online education in Africa. Initiatives to advance digital learning date back as far as 1997 when the World Bank sponsored the creation of the African Virtual University (AVU), a pan-African institution that has since grown exponentially utilizing a satellite-based delivery system.

According to its latest publicized annual report [114], AVU had by 2015 trained “63,000 students across Africa and … established the largest network of Open Distance and eLearning institutions with 53 institutions in over 30 countries in sub-Saharan Africa.” AVU is now slated [115] to become part of the Pan African University, a postgraduate institution funded by the African Union (AU). Rebranded as the “Africa Virtual and E-University,” the institution is expected to provide ODL in virtually all African countries, and offer programs in English and French.

AVU is just one of several online universities that have sprung up across Africa. Others include the University of Africa [116], Unicaf University [117], the Virtual University of Uganda [118] and the Virtual University of Senegal, an institution that reportedly enrolled 20,000 students [119] in 2017/18. Traditional universities are also rolling out online programs at an accelerated pace. Prominent distance education units at established universities include Wits Plus [120] at the University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa), the Distance Learning Centre [121] of Ahmadu Bello University (Nigeria), or Kenyatta University’s Digital School of Virtual and Open Learning [122] (Kenya).

These trends, as important as they are, are likely just the beginning of a drastic expansion of Africa’s nascent digital learning market. Companies of all shapes and sizes are entering this market in various corners of the continent. Launched in Zambia in 2015, the company Mwabu [123], which distributes e-learning content to 180,000 elementary students via tablets, intends to eventually reach 100 million learners [71]. In South Africa, Eneza Education delivers learning content, including national school curricula, via mobile cell phones. It currently claims 2.1 million [124] registered learners.

Other examples of new digital providers include the Rwanda-based Kepler University [125], which offers online degrees in partnership with Southern New Hampshire University in the United States. The small but fast-growing company Getsmarter [126], meanwhile, offers online certificate programs in collaboration with top international universities like Harvard. Digital learning is also increasing its presence in vocational education: The company Edacy [127] combines MOOCs with short industrial apprenticeships. Distance learning in vocational education is explicitly promoted [128] by the South African government.

Most African governments now also have policies that urge Information and Communications Technologies (ICT) penetration and digital learning. Kenya’s government, for instance, in 2016 launched a Digital Learning Program [129] to digitize elementary education. By March 2018, more than one million laptops and tablets pre-loaded with interactive digital content had been delivered to 19,000 public schools [130]. Rwanda, one of Africa’s ICT pioneers [131], similarly plans to turn all its classrooms into wired, “smart” classrooms [132] by 2020 in partnership with Microsoft. In higher education, the government is developing a National Open and Distance ELearning Policy and plans to offer online distance education at the University of Rwanda – an initiative that is supported by UNESCO [133].

The Indian government and 47 AU member countries, meanwhile, have signed on to the Pan-Africa e-Network Project [134], a large-scale initiative [135] that connects Indian and African universities via a tele-education software system, using a satellite hub station in Senegal [136]. The initiative also connects African medical facilities with medical specialty hospitals in India, enabling Indian doctors to review digitized medical records in Africa and provide live tele-consultations.

Overall, the market volume of self-paced e-learning alone doubled [137] in Africa between 2011 and 2016, according to the market research firm Ambient Insight. Another research firm, IMARC, found that the e-learning sector in SSA grew by 15 percent annually between 2010 and 2017, reaching a value of more than USD$690 million in 2017 [138]. The e-learning market on the continent is projected to further grow to USD$1.5 billion by 2023. The use of digital learning management systems is also showing signs of vigorous growth. There is no question that there is tremendous potential for digital education in Africa, especially given the increasing Internet penetration on the continent.

The Digital Divide in Sub-Saharan Africa Is Narrowing

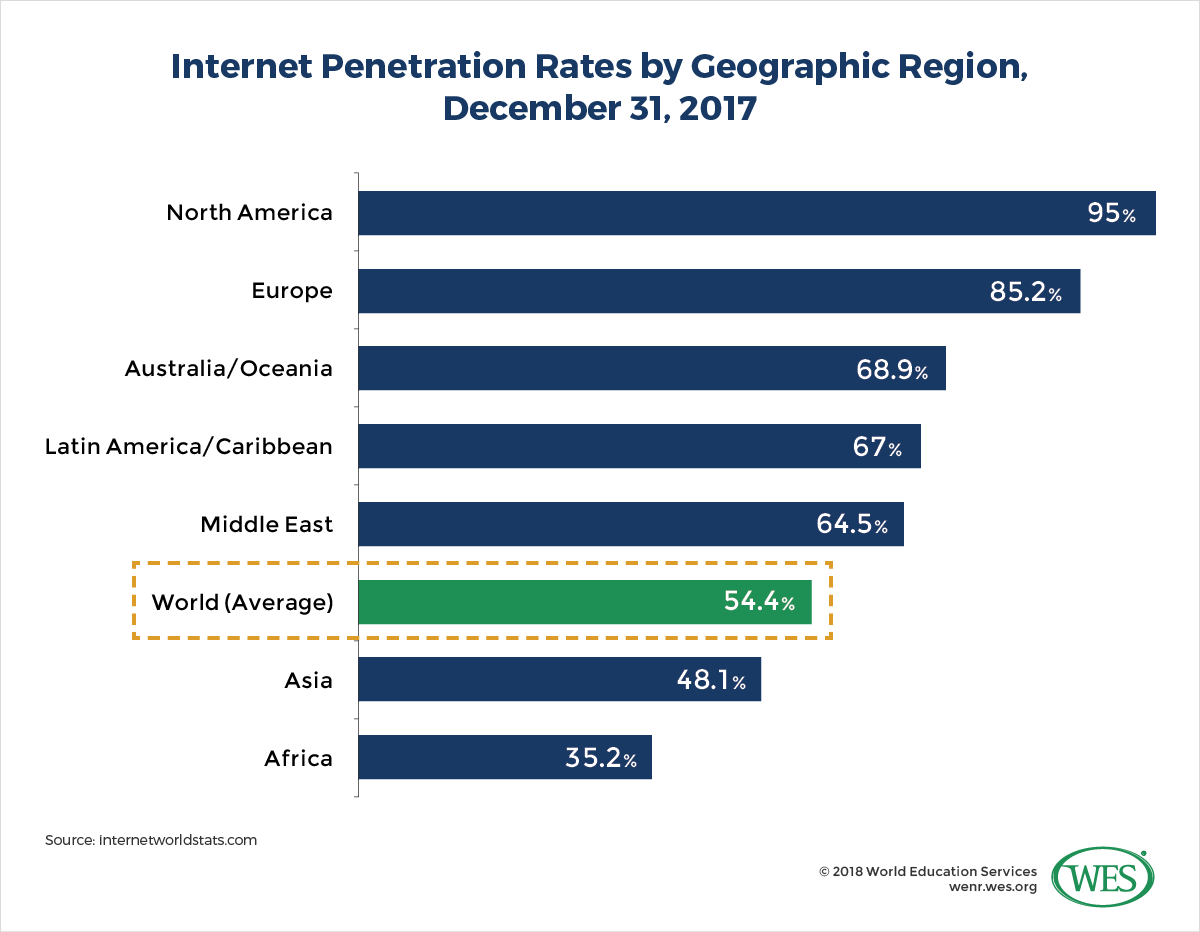

Africa still trails far behind other world regions in terms of Internet penetration. Only 18 percent [139] of households on the continent had an Internet connection in their homes in 2017, compared with 84.2 percent in Europe.

It should be noted, though, that Internet penetration in Africa varies considerably by country and region. While a majority of urban Africans now have mobile devices and access to mobile broadband Internet, many people in remote rural areas lack personal access have to use the internet at “public facilities like schools, universities and internet kiosks, which are connected via satellite terminals, often powered by solar power [140].” Likewise, Internet usage rates in countries like Kenya or Mali are as high as 85 percent and 65 percent, but they hover below 6 percent [141] in countries like Burundi, the Central African Republic, or Chad.

However, the continent is catching up fast, fueled by the spread of more affordable smartphones and mobile data plans. “Mobile development has enabled Africans to ‘leapfrog’ poor landline infrastructure, which has been a brake on progress. Many Africans get their first Internet experience on a mobile rather than a desktop computer [142]….” In fact, mobile phones are now spreading so fast that Uganda is said to have three times more cell phones than lightbulbs [143].

Market watchers expect the total number of mobile broadband connections in Africa to more than double from 419 million in 2017 [144] to 1.07 billion by 2022, with 5G advanced mobile technology expected to arrive at the beginning of the next decade. According to a recent report [145] by the British social media marketing agency We Are Social, the number of African Internet users increased by 20 percent between 2017 and 2018 alone, with users “in Mali increasing by almost 6 times since January 2017. The number of Internet users in Benin, Sierra Leone, Niger, and Mozambique has more than doubled over the past year too.” Even by more conservative estimates, at least 40 percent [146] of people in SSA will have some form of Internet access within seven years.

To put these trends in context, Africa’s fixed landline broadband infrastructure is still marginal—more than 90 percent of all Internet connections on the continent are via mobile networks [147]. Desktop and laptop ownership is also rare, so that digital learning in Africa will mostly occur on mobile devices for years to come. This usage, however, is in line with global shifts toward mobile technology. The increased processor speed of mobile devices now allows the use of applications that were previously accessible only on desktop computers [148].

Sharply Rising Internet Penetration in South Asia

South Asia is the world region with the second lowest Internet penetration worldwide with a user rate of 36 percent [149] in 2018. However, Internet usage is spreading fast, if varying by country. India in 2016 overtook [150] the U.S. as the country with the second largest number of Internet users in the world after China. Between 2016 and 2017, the number of mobile Internet users in India grew by fully 17.2 percent to 456 million, reaching a penetration rate of about 34 percent [149].

That rate is going to rise quickly: The number of mobile Internet users is estimated to swell by an additional 330 million [146] by 2025. As in Africa, this growth is largely attributable to affordable mobile devices and reduced prices for data plans—79 percent [149] of all Web traffic in India currently takes place on mobile phones. India also has a similar urban-rural divide: While mobile Internet penetration in the cities stood at 59 percent in 2017, rural India trailed far behind with only 18 percent [152].

India’s government is currently rolling out a new digital communications policy [153] that aims at bringing fixed-line broadband connections to 50 percent of Indian households, as well as to communications towers in rural regions, by 2022. While some observers doubt [154] that this objective can be achieved, India is poised to take a massive “digital leap [155]” in the years ahead. By some estimates, 1.2 billion Indians will have a smartphone by 2030. The volume of India’s online retail business alone is projected to surge by 1,200 percent [156] by 2026.

Bangladesh, meanwhile, already has a higher Internet usage rate than India’s. According to the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission, 85.9 million people—slightly more than 50 percent of the population—had an Internet subscription in April 2018 [157]. That number represents an astronomical growth rate over the rate in 2010, when merely 3.7 percent of Bangladeshis were using the Internet, according to the World Bank [158]. The country adopted a proactive digitization strategy [159] that essentially brought half of the population online within just a decade. Mobile network coverage now extends to 95 percent of Bangladesh’s geographical area, including remote islands [160]. As a result, Bangladesh has become the second largest [161] supplier of online freelance laborers worldwide after India.

In Nepal, the growth in Internet usage has been equally impressive. The percentage of Internet users in the Himalayan country skyrocketed from 1.97 percent [162] in 2009 to 55 percent [149] in 2018. Digital access in Pakistan, on the other hand, is still nascent. Only 22 percent [149] of Pakistanis use the Internet, despite notable growth rates in past years. The country’s online use remains characterized by distinct digital divides—not only between urban and rural regions, but also between the sexes [163].

Going Digital: Strong Growth in Online Education in India

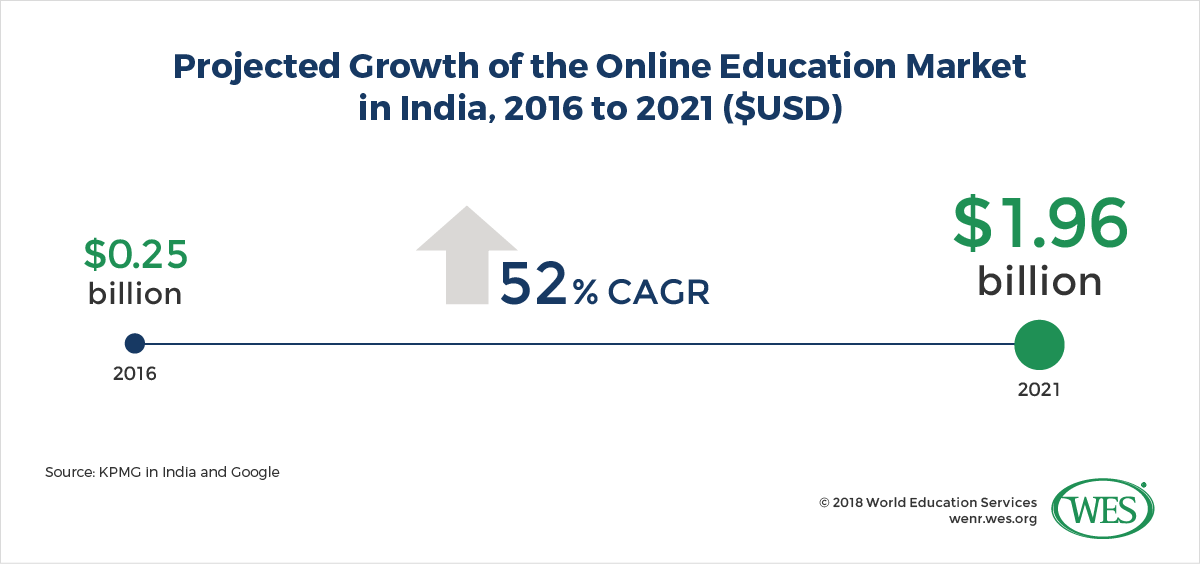

Rising Internet use in many parts of South Asia has opened the doors wide for digital education. By most [164] accounts, India is already the second largest online education market after the United States. The consulting firm KPMG and technology company Google project that the value of India’s digital learning market will grow eightfold within just five years, from USD$247 million in 2016 to USD$1.96 billion by 2021 [165].

Online education in the country exists in various forms, including vocational reskilling certificates, test prep programs, and language courses. Supplementary online courses in elementary and secondary education are projected to grow the most until 2021, but online higher education is also expected to grow by 41 percent, with online MBAs being the most popular. Speaking to the news website Quartz, Nitin Bawankule, industry director of Google India, noted [166] last year that increasing Internet penetration has coincided with growing interest in online education in Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities.

India’s government supports this trend. After curbing [168] online and distance education programs in 2017 because of problems with quality and the spread of non-recognized programs [169], the UGC recently reinstated [170] online degree programs for the 2018/19 academic year. It notes that these programs “are a big step towards attaining the targeted GER of 30% by the year 2020 [171].” India’s human resource development minister, Prakash Javadekar, recently affirmed [172] that India will be “creating an enabling environment where not just students but working executives can study and earn a degree without traveling the distance.”

To ensure quality, only HEIs that have been in existence for at least five years and are rated A+ by the National Assessment and Accreditation Council will be allowed to offer online programs [170]. Public open universities are not affected by these restrictions: About 15 percent of India’s universities will soon be able to provide existing degree programs wholly online, as long as the programs aren’t in disciplines that require lab courses or other hands-on study. Authorized universities can offer programs online that lead to certificates, diplomas, or degrees, using video lectures, online materials, and discussion forums [171].

This policy change is just one example of several digital learning initiatives pursued by the Indian government. In 2016, for instance, the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) launched SWAYAM [173] (Study Web of Active Learning for Young and Aspiring Minds), an interactive online learning platform of free MOOCs that incorporate video lectures, reading materials, online discussion forums, downloadable assignments, and tests. Some courses offer credit that can be transferred into university programs. The UGC aggressively pushes these MOOCs. It recently issued a directive that “no university shall refuse any student for credit mobility for the courses earned through MOOCs [174].”

One year after SWAYAM’s launch, the MHRD minister announced that 60,000 students had completed study courses and boasted that SWAYAM had made “knowledge available anytime anywhere” like an “ATM offers cash [175].” Indian authorities [176] have hyped SWAYAM, which is slated to offer 2,000 courses, as “the world’s biggest repository of interactive electronic learning resources under a single window.”

Other ongoing digital initiatives include the National Programme on Technology Enhanced Learning (NPTEL [177]), a program that delivers Web-based courses in engineering and science, and the National Academic Depository. The latter is a digital depository of degree certificates and academic transcripts that allows employers and academic institutions to verify credentials online. Formally launched in 2017, the depository was developed to help stem the circulation of fake degrees. It currently contains 11 million credentials from 218 participating HEIs [178].

MOOCs offered by private providers, meanwhile, are also spreading like wildfire, most notably in the tech hub of Bangalore. The U.S. provider edX registered a 73 percent [179] growth rate in India in 2016. Coursera, meanwhile, reported in July 2017 that the number of Indian users had grown by 50,000 each month [22] throughout the first half of the year. Many Indian MOOC students are working professionals interested in flexible, career-relevant courses. It will be interesting to see how well the public SWAYAM can compete with Western providers.

In sum, online education in India is growing at breakneck speed. The government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, determined to rapidly digitize Indian society, launched a comprehensive Digital India [181] initiative in 2015. Beyond that, online education is considered vital for increasing capacity and upskilling the population.

Beyond India: Digital Initiatives in Other South Asian Countries

Digital education is on the rise in other South Asian countries as well. In 2016, Bangladesh digitized its entire elementary school curriculum [182], enabling 20 million elementary school students to access all their learning materials on cell phones. The Bangladesh Open University, a public mega-university of more than 500,000 students, began rolling out fully online programs the year before, in 2015. It plans to eventually stop using print materials [183] altogether. Educational institutions are speedily being equipped with multimedia classrooms and laptops [184]. The country pursues an aggressive digitization strategy [159] that runs the gamut from pushing online banking to the construction of IT villages and a new public virtual university [185] in an innovative high-tech park [186]. Bangladesh recently expanded its international fiber optic submarine cable infrastructure and launched its first communications satellite [187] in 2018.

Academic institutions in Nepal, likewise, are increasingly rolling out distance learning programs via online delivery. India’s IGNOU has established two regional centers in Kathmandu and partnered with several Nepali providers. Indicative of the growing demand for distance learning, Nepal in 2016 launched the Nepal Open University [188], the country’s first public open university. The institution delivers master’s programs using tools like online videoconferencing [189] and digital libraries. Meanwhile, organizations like Open Learning Exchange Nepal [190] provide underresourced rural schools with interactive educational software. As of 2015, the organization had delivered nearly 6,000 laptops to such schools, created a digital library of thousands of books [191], and developed more than 600 digital learning modules.

Digital education is also spreading in Pakistan. As early as 2002, Pakistan’s government founded the Virtual University of Pakistan [192] to accommodate mushrooming demand [193]. The institution is now one of Pakistan’s largest universities enrolling more than 100,000 students. More recently, the Higher Education Commission launched a Smart Education [194] initiative that seeks to digitize HEIs by introducing blanket WIFI coverage on campuses and distributing 500,000 laptops, to be followed by the creation of e-classrooms to facilitate digital learning. Smaller initiatives and providers [195] are popping up throughout the country as well. For instance, the All Pakistan Private Schools Management Association in the province of Sindh recently introduced an online education portal [196] for elementary and secondary schools.

Compared with MOOC enrollment in India, Pakistan’s is low and held back by limited Internet penetration. The outlook for online courses is nevertheless positive [197]–90,000 students took a MOOC on the edX platform alone in 2016 [198]. The Aga Khan University was the first in Pakistan [199] to offer a locally designed MOOC in 2014. More recently, the private Information Technology University in Lahore entered an agreement with edX, in which it will integrate edX’s MicroMasters programs into the university’s curricula and degree programs [200].

Overall, the digitization of Pakistani society is slowly progressing in various spaces. For instance, Pakistani authorities now use a digital management and monitoring system to track schoolteachers and curb [201] the problem of teacher absenteeism and ghost teachers [202]. As stated earlier, the number of self-employed Pakistanis freelancing online [203], meanwhile, has risen in recent years—a trend that turned Pakistan into one of the world’s largest hubs for remote freelance labor [204].

Flexible and Cost-Effective Education: The Benefits of Digital Learning

There are countless examples of how digital learning can improve people’s lives. Online education has been effectively used to extend learning opportunities to displaced refugee populations [205] and, as previously noted, marginalized populations in remote rural regions.

E-learning certainly has a number of distinct advantages over brick-and-mortar education. It eliminates the costs of printed teaching materials and the need for physical infrastructure, and can therefore be delivered in regions where such infrastructure does not exist.

It can reduce costs not only for academic institutions, but also for students who often have to travel long distances to schools and universities in regions like SSA. Online education class schedules are usually flexible, and course materials are typically accessible anytime, making study easier for working adults. Digital libraries provide access to literature where no physical libraries exist.

Crucially, e-learning is not limited by the size of physical classrooms—online courses can be taken by an unlimited number of students around the globe, whether they’re in Accra, Bogota, Delhi, Dhaka, or Lagos. As access to electricity and broadband Internet increases, online education will quickly become accessible to ever-larger audiences. And distributing inexpensive tablets to students is still cheaper than building brick-and-mortar institutions. It is therefore not surprising that academic institutions and governments in SSA and South Asia are increasingly pushing online learning, a comparatively cost-effective investment in human capital development.

Non-recognized, Insular and Neocolonialist: The Downsides of Digital Learning

At the same time, some think that the current dominance of Western providers in e-learning markets smacks of the re-colonialization of the academic space in developing regions. As international education scholar Philip G. Altbach has argued [206], the spread of Western MOOCs is the “neocolonialism of the willing”: The adoption of Western, English-language online courses in developing countries tends to perpetuate the hegemony of Western countries in global education.

Indeed, a world where youngsters from Kampala to Karachi recycle the same canned learning content developed in California or Massachusetts may lead to an undesirable intellectual homogenization. It is vital for countries to develop their own local learning content in local languages. India’s SWAYAM is a step in the right direction. As more local providers enter the e-learning market and online learning becomes more common in the developing world, it stands to reason that MOOC content will evolve beyond Western-produced courses.

Another problem is the lack of recognition of MOOCs and other forms of online learning. While a degree from a distance education university like IGNOU may not be comparable to a degree from a top research university, it is still a qualification that opens access to employment and further academic study.

A completion certificate for a Coursera MOOC, on the other hand, is currently not a viable form of academic currency. Many online providers still operate outside of established quality assurance and accreditation frameworks. Beyond that, all forms of distance education, be they formally accredited or not, still have to overcome the barrier of a low reputation. Online education is also unsuitable for disciplines that require practical, hands-on training (unless offered as part of a blended model approach).

The most common and closely related criticism of online learning, of course, is that it is an inferior, isolated, anonymous learning experience. In this view [207], online learning provides a sterile environment that cannot compete with the real-world, tangible and touchable learning environments in which it is much easier for students and teachers to interact and exchange ideas. This notion is still widespread: A 2011 survey [208] of 4,564 U.S. university instructors found that nearly two-thirds of them considered e-learning outcomes to be inferior to those involving traditional face-to-face courses.

Several examples illustrate the shortcomings of online education. For example, dropout rates in online programs tend to be higher compared with those of traditional programs. A recent study [209] by the University of California, Davis concluded that grade averages and completion rates of students in online programs at community colleges were significantly lower than in traditional programs. In India, likewise, dropout rates in distance education programs [210] have been found to be higher than in traditional programs. Completion rates in MOOCs are even worse. Research from 2013 found that less than 7 percent [211] of enrollees in a sample of 29 MOOCs completed their courses.

Many analysts have argued that online education is much less suitable to first-time students than students who have prior education, since the latter have already acquired real-world academic skills—a circumstance that would limit the potential of e-learning as a means of expanding capacity. Enrollees in MOOCs, in fact, are often postgraduate students: In 2013, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania that surveyed Coursera MOOC participants noted that more than 80 percent [212] had either a two- or four-year post-secondary degree. Among participants in Brazil, China, India, Russia, and South Africa, the vast majority of participants came “from the wealthiest and most well-educated 6% of the population,” according to the researchers.

In developing countries, the mere provision of access to technology and digital content alone is certainly not enough to motivate students to embrace digital learning. The distribution of laptops pre-loaded with learning content to 800,000 public schoolchildren in Peru has been largely unsuccessful [213]. While the pupils used the laptops for games and social media, they did not connect with them for learning purposes.

The Peruvian example illustrates the need to supplement digital learning programs with training for inexperienced teachers in how to use computers in elementary education [214]. But the need to bridge such gaps in know-how are evident even at the university level. IGNOU, for example, supplements online programs with face-to-face tutoring at learning centers. This approach is well-founded: A number of studies show that it is blended learning models that are most effective [215], not programs offered exclusively online. Hybrid approaches are perhaps the most promising, highest quality model going forward. Former President of Stanford University John Hennessy considers the flipped classroom model, which combines online lectures with classroom instruction, “as effective as traditional lectures [216].”

Like It or Not, Digital Learning Will Change Global Education

What these problems suggest is that digital learning is still experiencing growing pains. But even e-learning detractors have to acknowledge that the spread of digital education cannot be stopped—it will slowly but surely transform the shape of education in many parts of the world. As this article illustrates, governments and academic institutions in SSA and South Asia are swiftly adopting digital learning models, despite persistent technological barriers. In light of current developments and trends, it’s probably safe to assume that digital education in these regions will grow exponentially.

Current e-learning models are imperfect. In the future, educators and policy makers developing these models will need to work out how to best conceptualize and utilize online learning and improve the delivery and content of online courses, while making them more interactive and relevant to local contexts. At any rate, younger generations that grow up hooked on mobile devices and have a large share of social interactions online will be more receptive to digital education. U.S. employers, for instance, are already more accepting [217] of online degrees than in the past decade.

Irrespective of quality concerns, ballooning demand will drive the spread of digital education, akin to the fast-growing privatization of education. The number of tertiary students worldwide is estimated to grow from 214.1 million in 2015 to 594.1 million by 2040 [218], with developing regions like SSA and South Asia experiencing high growth rates. As discussed earlier, governments there face nearly insurmountable challenges in building costly brick-and-mortar institutions amid rapidly surging demand.

To be sure, “tablet teachers”, interactive lectures and online chat forums alone are not a substitute for face-to-face interactions with professors and peers, a vital aspect of learning. It is difficult to see how education delivered exclusively online could ever produce world class scholars. As argued here, however, e-learning will play an increasingly important complementary role in mass education, driven by the need to reduce costs and accommodate demand.

The way current trends are shaping up, the rationalization and streamlining of education in developing regions will take digital education to new heights. Underprivileged social segments will increasingly be educated via “m-learning,” using mobile phones; while elite universities will progressively incorporate digital content into blended learning models. Online education will also be increasingly used in vocational education and to upskill adult learners. Furthermore, top research universities in Africa, for example, will be able to share costs and pool resources using tools like shared digital libraries and digital communication facilities that will help connect institutions across the continent in transnational research clusters.

1. [219] Tuition fees for master’s degrees delivered by U.S. universities on the Coursera platform, for example, presently range from USD$15,000 [7] to more than USD$19,000. Paywalls have also become common for shorter MOOC-type programs.

2. [220] In education, “massification” usually refers to a process of inclusion of mass audiences in higher education, making it accessible to large segments of society and not just the elites.

3. [221] Other estimates are higher. Projections depend on the definition of “middle class.” A prominent 2011 study [222] by the African Development Bank found that Africa’s middle class had increased from 27 percent in 1980 to 34 percent in 2010, giving rise to the notion that Africa could become “the next Asia [223].” However, these estimates are now largely considered overhyped [224].

4. [225] According to projections [72] by the British Council from 2014.

5. [226] Calculation based on data provided by the World Bank and the National Center for Education Statistics [227].

6. [228] Reported student numbers vary. IGNOU reports “over 3 million students” on its website (as of 2014), while news reports from 2012 suggested 4 million students [229]. The Open University of China lists 3.59 million registered students on its website [230]. But whereas IGNOU is widely regarded as the world’s largest university, the Open University of China is usually not included in such tallies.