Deepti Mani, Research Associate, WES

[1]At a time when international students’ interest in a U.S. education has notably softened, pathway programs run by third-party providers promise higher education institutions (HEIs) the ability to maintain or even increase international enrollment numbers. Such programs exist in order to give academically qualified students from abroad who aren’t proficient in English the chance to come to U.S. campuses and enroll, after a time, in mainstream academic programs where they can earn high-quality degrees. Such third-party providers offer institutions a quick route to meeting enrollment goals.

[1]At a time when international students’ interest in a U.S. education has notably softened, pathway programs run by third-party providers promise higher education institutions (HEIs) the ability to maintain or even increase international enrollment numbers. Such programs exist in order to give academically qualified students from abroad who aren’t proficient in English the chance to come to U.S. campuses and enroll, after a time, in mainstream academic programs where they can earn high-quality degrees. Such third-party providers offer institutions a quick route to meeting enrollment goals.

However, the programs are rife with potential risks. These include the admission of underqualified students, poor-quality academic offerings, significant reputational harm, and more. The key to managing these risks, say those experienced working with such providers, often comes down to laying a solid foundation at the contract stage.

To better understand the considerations at play, the WES research team reviewed a number of contracts between U.S. HEIs and top pathway providers. We also conducted interviews with individuals who have firsthand experience implementing such programs, and reviewed secondary literature. The literature and the interviews form the basis of this article, which focuses on recommendations about points to consider during the selection and negotiation phases of entering a contract with a pathway provider.1 [2]

Advice From the Field: Establish Expectations Among Core University Staff Upfront

A director of international admissions at a private U.S. university that works with a pathway provider notes that when it comes to expectations about academic quality, student progression, and more, internal “workflow discussions” around the delivery of academic programs are vital. Her advice is, before beginning contract negotiations with an outside provider, university staff should meet internally to address expectations of each partner’s responsibilities for a range of issues including:

- Program design and delivery

- Workforce management

- Partnership governance

- Academic program delivery

Delivery of Academic Services

Given the fact that nothing cuts closer to the heart of higher education than the quality of academic programs, it makes sense that academic credit – together with the guarantee of progression from the pathway program into a degree program – would be one of the most critical aspects of negotiations between institutions and pathway providers.

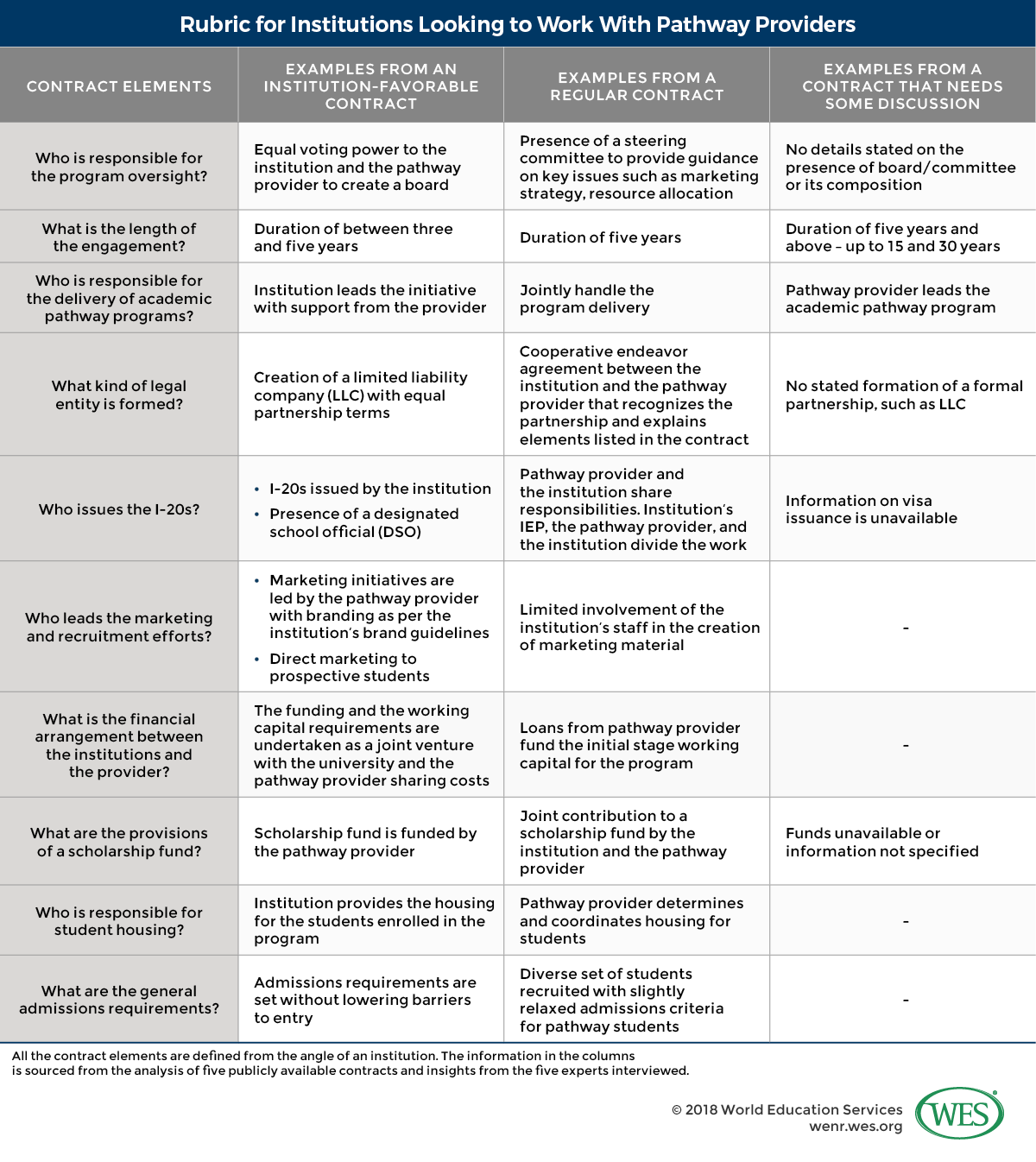

Such decisions are usually (but not always) controlled by the university. A review of contracts shows a range of approaches to academic delivery:

- The institution is in charge of the delivery of the academic portion of the pathway program. Three of the five contracts reviewed state that the institution is in charge of the delivery of academic pathway programs and the English language programs. Of these three, one carries out the delivery through an academic director, whose responsibility also includes selecting the delivery staff and supervising them for program delivery.

- The institution and pathway provider work jointly. According to the terms specified in one of the contracts, the academic program is prescribed for joint development. The university is responsible for providing services to the pathway provider employees, who oversee the academic program delivery. Together, the institution and pathway provider establish a team focused on policy and process issues relating to all academic aspects of the student experience. These include teaching and resources, and staff training and development.

- The pathway provider leads the academic pathway program. One of the five contracts requires the pathway provider to ensure that faculty members are present and engaged for “ancillary courses”2 [3] and for courses eligible for “degree credit.”

Recommendation

A pathway specialist we interviewed notes that the “best barometer to judge the success of a program is the growth in the learning levels of the students admitted.” Schools should consider tracking students’ learning levels pre- and post-pathway program and use the data to improve learning outcomes. She recommends including this process in the contract as a line item. The same specialist recommends that institutions also form “focus groups [composed of students] to gauge the adjustment levels of students both culturally and socially.” These groups can help to track the progress of conditionally admitted international students/pathway students, and provide comparisons to the directly admitted students, including academic performance.

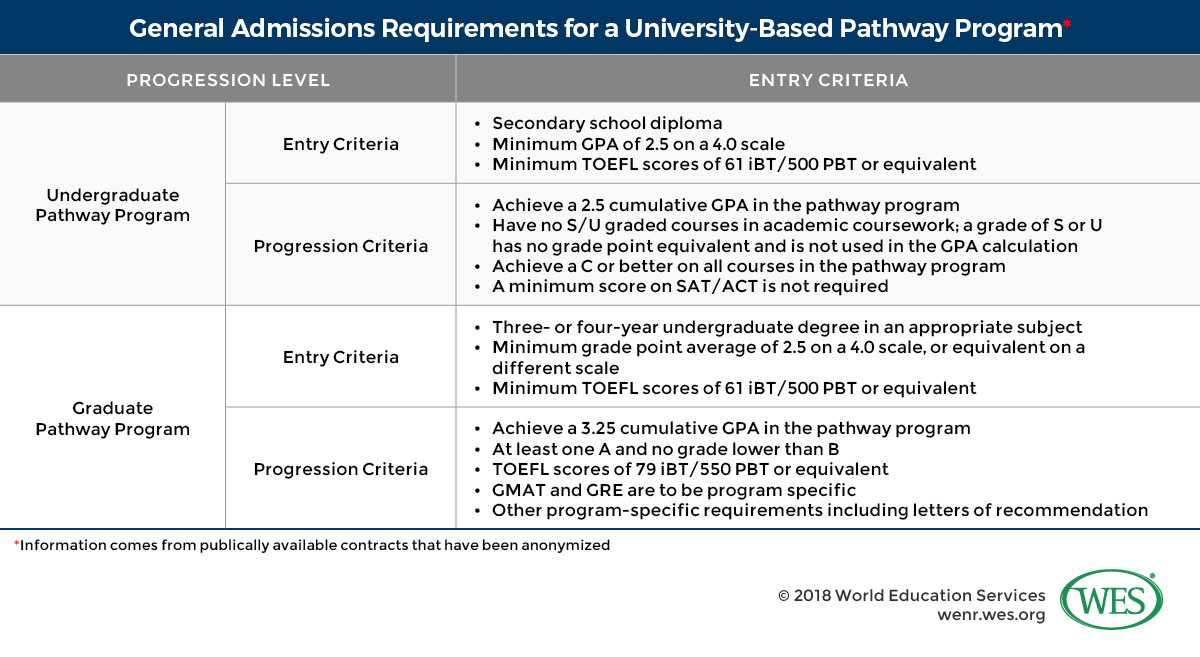

General Admissions Requirements

Each contract we reviewed goes into varying levels of detail on the admissions requirements for graduate pathway and undergraduate pathway programs. While one contract emphasizes keeping the “entry requirements slightly lower than those for direct admission,” a few others just detail the GPA and IELTS score requirements and other entry criteria.

The chart below shows a sample of the general admissions requirements as articulated in a contract between an institution and a pathway provider.

Advice From the Field: Admissions Requirements and Fraud

In the contracts we reviewed, admissions requirements for students entering pathway programs varied widely. The risk inherent in such variations is that lower barriers to academic entry [5] will jeopardize the quality of students admitted, putting the students at risk of failure and creating a range of challenges for the admitting institution. The fact is that pathway providers are often focused on volume and so may make admissions decisions very quickly. Especially given that fraudulent degrees are rampant [6], it is incumbent on institutions to ensure that the pathway providers with which they contract have an effective approach to evaluating the academic credentials claimed by applicants.

Governance Structure

Another of the most critical contract negotiation items is the determination of who oversees the program. Typically a board or steering committee has a role. The contracts we reviewed elucidated the following types of arrangements:

- Presence of a board. Three out of five contracts mention the presence of a board of directors. The board usually comprises representatives selected by both provider and institution, with equal votes.

- Presence of a steering committee. One contract mentions the presence of a steering committee without delving into its composition. Making use of a steering committee is “an ideal practice,” according to one industry expert we interviewed. She adds that currently, steering committees “tend to be more organic than structured,” while another interviewee, a director of international admissions at a prominent U.S. university, believes that “everyday management would significantly improve with the presence of [a steering committee].”

- Executive leader and a joint board. In one out of the five contracts, the pathway provider, upon consultation with the university regarding finalists for the position, is responsible for appointing an executive director to lead the day-to-day operational management at the institution with the support of a board made up of pathway and institutional representatives – “the Joint Strategic Management Board.”

Finance: Fees, Reimbursements and Residual Cash Flows

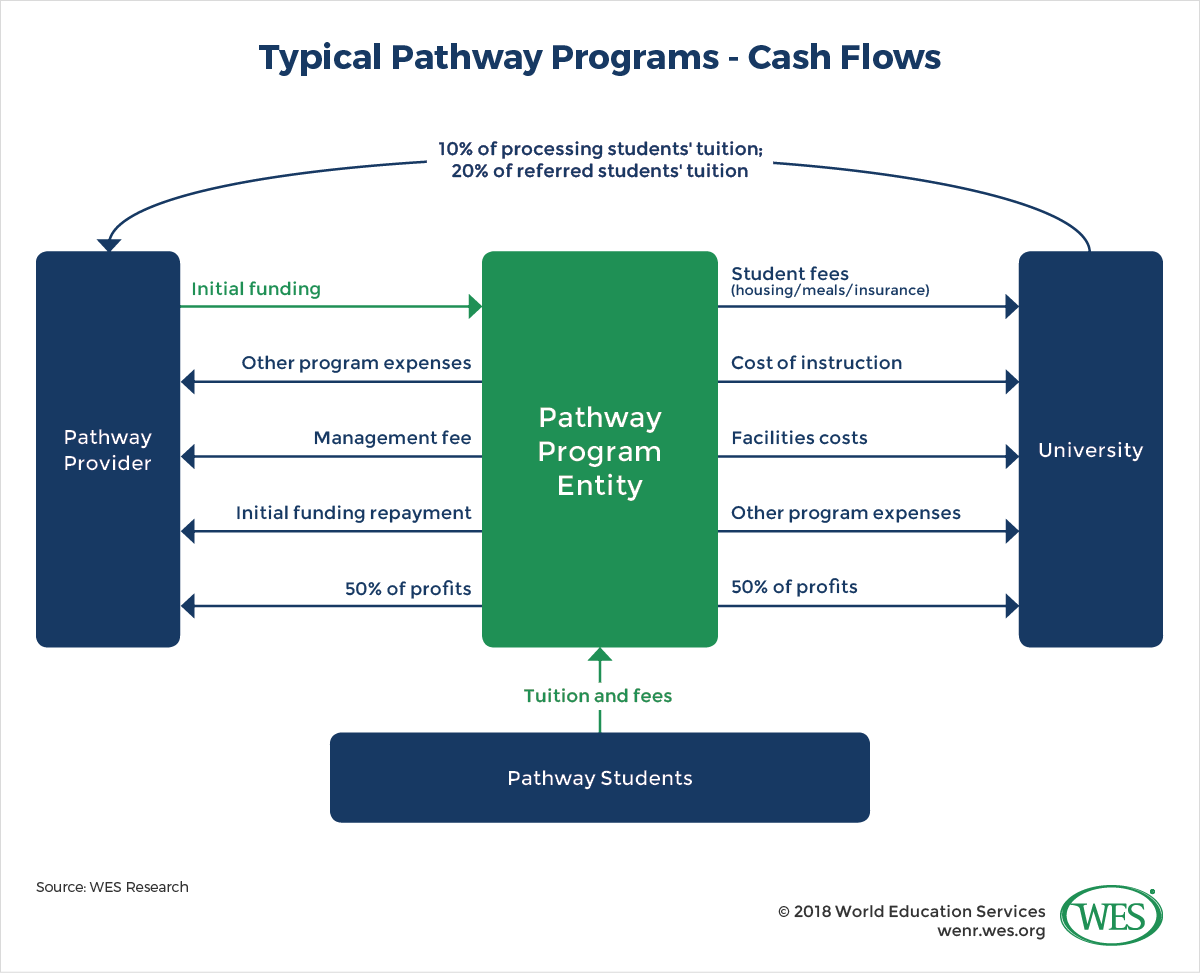

In the contracts we reviewed, a pathway entity is established that generally collects revenues consisting of tuition from students. The entity will disburse funds to the partners (the pathway provider and the university) according to pre-defined rules. For example, if the university provides instructors for the program, they are compensated by the entity. Similarly, if the university is providing buildings for classes, administration, or living quarters for the students, the university is generally reimbursed by the entity for these contributions.

The institution will generally pay the pathway provider a fee based on a percentage of tuition for the students that it recruits and enrolls. These fees range from 15 percent to 20 percent of tuition. These are often higher than the fees paid to agents. The university will also continue to pay the pathway provider a fee based on a percentage of tuition, typically 10 percent, for students’ sophomore, junior, and senior years at the university.

The pathway provider is entitled to receive a repayment of any financing it provides to the pathway entity for deficits incurred in the start-up phase.

Many agreements entitle the pathway provider to collect an annual management fee for operating the pathway entity. These fees vary, but can reach several million dollars annually. After all expense reimbursements, recruiting fees, repayment of funding by the pathway provider, and management fees are paid to the pathway provider, residual profits (if there are any) are split between the two partners, usually evenly.

These cash flows are illustrated in the diagram below:

Agreements must address the following:

- Performance standards. Most agreements call for minimum performance standards by the pathway provider. Generally, these are based on a minimum number of students enrolling in the program, and a percentage of these students progressing to the university’s regular academic programs. Failure to meet these standards for an extended number of years provides the university a reason to terminate the agreement.

- One contract offers an incentive to maximize the number of students enrolled in the program. “The Partnership” (as the program itself is titled in the contract) pays the pathway provider an annual incentive fee equal to a certain percentage “of the annual revenue of the partnership for each fiscal year.”

- Another contract stipulates that enrollment cannot dip below a “minimum of 12 enrolled students.” With fall intakes the most heavily subscribed, followed by spring and summer intakes, the pathway provider is to make reasonable efforts to ensure that student enrollments are spread across the commencement dates of the pathway programs.

- Financial comparison: Evaluating a third-party pathway agreement should involve a financial projection of an expected range of outcomes, including the net cash flow to the university from the operation of a partnership compared with the operation of an international recruitment effort by the university on a stand-alone basis.

The subject of payment structuring is one of the most time-consuming, complex, and elaborate processes in the entire contract negotiation phase. While each university takes a unique stance based on factors that range from internal staff buy-in to the institution’s need for international student recruitment, it is always helpful to go over a few housekeeping items.

One expert we interviewed noted, “What makes the process more complicated is the necessary buy-in from a large set of people.” She advises bringing in the necessary people early on to avoid missing essential line items, while ensuring the long-term financial well-being of the institution. That is to say, negotiations of some partnerships are handled at the executive levels of the university, and the international education staff may not be involved early on; bringing them in during the step-up phase would definitely be helpful.

Recommendation

Institutions should do a careful comparison of available alternatives: Continue international recruitment by university staff, or engage in a pathway program with a third-party provider. “Depending upon whether or not enrollment targets are met, it could be a long time before a university sees returns [by way of increased international enrollment] from the partnership,” noted one interviewee. This is especially true in cases of pathway partners providing substantial program funding up front.

Funding and Working Capital Requirements

Four of the five contracts we reviewed addressed this topic directly. We saw two main models:

- The pathway provider funds the initial start-up cost of the program. Two out of the four4 [8] contracts with clear terms on funding and working capital requirements lay out precisely that loans from the pathway provider will fund the initial stage of the program.

- The program is jointly financed. One contract states that the funding and working capital requirements will be undertaken as a joint venture – with the university and the pathway provider sharing costs. Another contract features a model that establishes payment responsibilities for the pathway provider and the university, alongside building in a provision for shared responsibilities.

Deal Structure

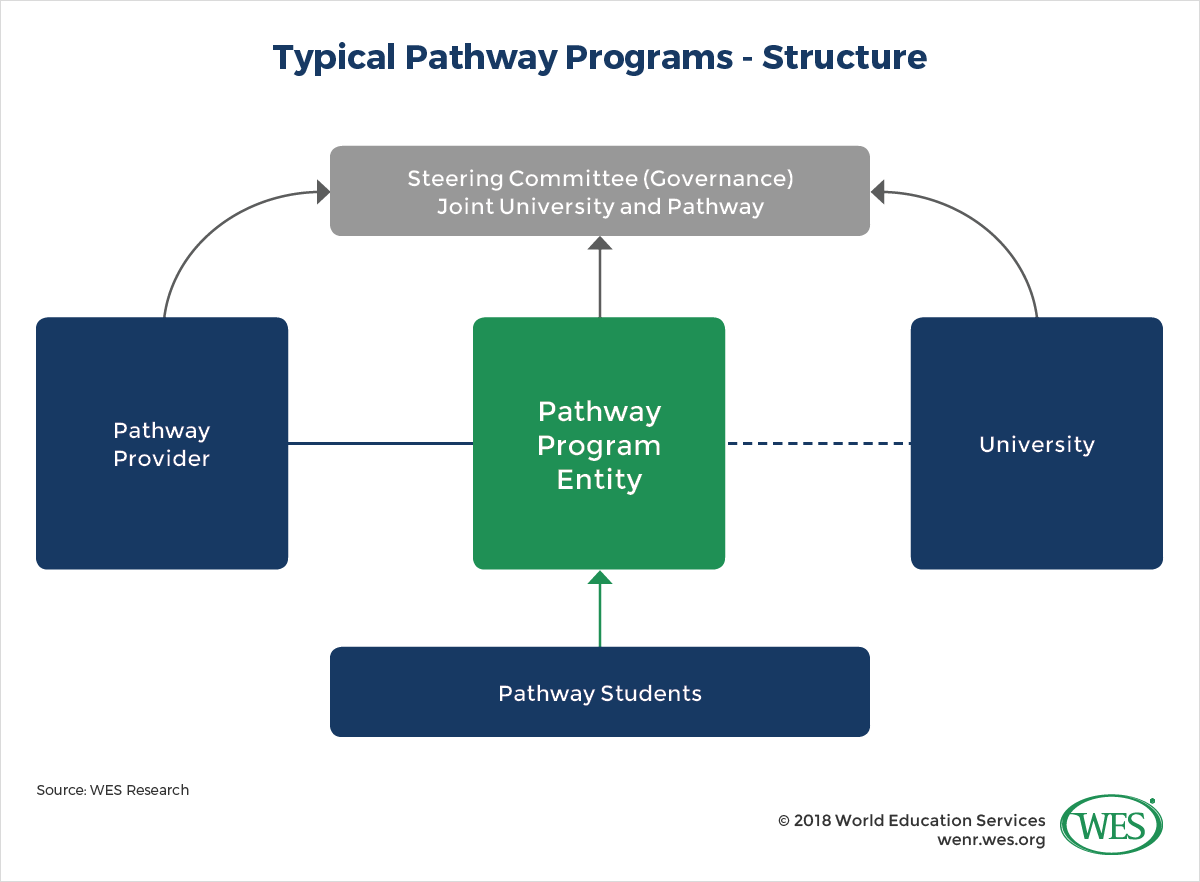

Among the contracts we reviewed, the partnership models between entities differ in structure. The partnerships took three primary forms:

- The contract forms a limited liability company (LLC). In this model, a legal entity (usually a corporation or limited liability company or LLC) is established and is jointly owned by the university and the pathway provider. One of the five contracts discusses the creation of an LLC with “equal partnership terms.”

- The pathway provider retains ownership. In this model, a legal entity is established and the pathway provider retains ownership. Residual profits may be shared between the parties, and the university may share governance. This model establishes a partnership in practice (even though one party holds ownership).

- The pathway provider acts as a vendor to the university. In this model a straightforward vendor relationship is set up. The pathway provider is paid a fee for the services it provides. One contract we reviewed describes the formation of a cooperative endeavor agreement5 [9] between the board of supervisors of the HEI and the designated representatives of the pathway provider partnership. This contract sets the tone for the third-party corporate provider to act as a vendor–to help the institution reach the enrollment numbers [10].

Recommendation

The first two entities above serve mainly to accumulate revenue and expenses associated with running the pathway program6 [11]. We suspect that different pathway providers have different preferences for deal structures. When negotiating, you can state your preferences based on your institution’s objectives, and test the flexibility of your partner; or choose the partner that is willing to structure the agreement based on your preferences. The diagram below illustrates the parties involved in the operation of a pathway program.

Length of the Engagement and Terms of Exit

The duration of each contract reviewed for this article varied substantially. Two contracts had term lengths of five years, two had term lengths of 15 years, and one contract had a term of 30 years.

Most of the experts we interviewed suggested that keeping the contract duration in the range of three to five years serves the institution’s interests best. A shorter term minimizes the risk that a contract will become outdated or ineffective for meeting the institution’s goals. All the contracts we reviewed also allowed for extension beyond the initial term period.

HEIs should ensure that there are sufficient clauses allowing for exit plans [13]. Each contract we reviewed stipulated circumstances, such as insolvency, as valid reasons for shortening the length of a contract or terminating the contract. Other reasons include:

- defaults on payment

- failure to meet goals stipulated in the agreement, including a specific recruitment target, or a material breach of other obligations

- failure to comply with legal requirements, and more

Recommendation

Institutions must do their due diligence when deciding which pathway provider to work with. This could mean obtaining detailed records of accomplishments, including proven enrollment growth and most recent numbers. Institutions should also conduct their own research and have an understanding of international markets independent of what the pathway provider presents to them. Here are some example questions to consider:

- What is the recruitment plan for countries like China, where we already have a very successful recruitment program? How can we ensure that our own recruitment efforts for regular program admission or intensive language programs are not cannibalized by our pathway partner’s efforts?

- How will a pathway provider help us in countries and global regions where it is more difficult to recruit students?

- How will pathway providers ensure that agents on the ground accurately represent our institution?

- How will pathway students be integrated into campus life, either during the pathway program or after they are mainstreamed?

The Issuance of Visas: I-20s7 [14]

In 2016, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement required that pathway programs must apply for I-20 certification by filling out the details of the program on the school’s Form I-17 (Petition for Approval of School for Attendance by Nonimmigrant Student).

As for the visa issuance outlined in the contracts we reviewed, all but one stated that the university issues the I-20. The other contract does not make clear who issues the I-20.

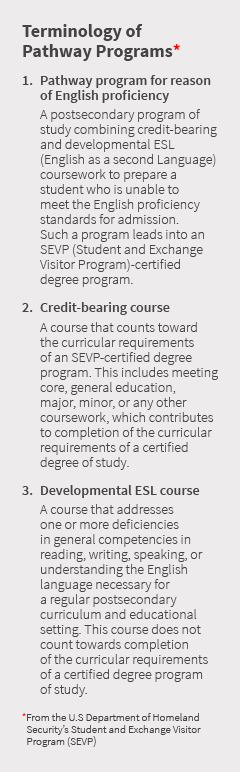

Varied interpretations of this provision [15] by both schools and the government have led the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP) to issue multiple guidelines [16] on the subject of conditional admission. A director of international admissions at a small private university told us that, “Students prefer their I-20s to come from the university and not the pathway provider [to avoid possibly running into any trouble with SEVIS].”

In the current political climate and given increased uncertainty around the duration of certain student visas, such concerns are likely only heightened. Clarifying procedures around I-20s is in the best interests of both students and institutions. One interviewee at a pathway program described a situation that was far from ideal: The pathway provider issued an I-20 for the pathway program; the university’s Intensive English Program issued an I-20 for any full-time ESL student; and the university issued the I-20 for directly admitted students. Promotion as a full-time student becomes unnecessarily complex under such a model.

It makes sense to define responsibilities related to the issuance of student visas in negotiations with pathway partners at the time of contract negotiations. It is also critical to stay apprised of the requirements of the United States Department of Homeland Security [17] for issuance of form I-20, Certificate of Eligibility for Nonimmigrant (F-1) Student Status – For Academic and Language Students.

Marketing and Recruitment

Pathway programs cannot take a cookie-cutter approach to marketing. As one interviewee noted, “Universities should internally decide the branding and messaging to ensure [it] gets communicated to the provider.”

Other sources recommend negotiating some accountability mechanism–for instance, the ability to approve or remove specific agents–to ensure that third-party agents employed by pathway programs to recruit students have adequate training and correctly represent the university’s brand, its status (public or private), its programs, and other details critical to students’ decision-making process.

In all the contracts we reviewed, pathway providers lead not just the recruiting but also marketing efforts. Some contracts provide highlights worth noting:

- One contract requires the pathway provider to use marketing materials that are in accordance with the style already used by the institution. The contract also stipulates that the partner institution must grant consent for pathway providers to use the materials without unreasonably withholding or delaying the process.

- Yet another contract mandates that the pathway provider collaborate with the partner institution to implement a comprehensive marketing strategy, which includes “direct marketing to prospective students, participation in various fairs and recruitment events” and “various e-marketing platforms including social media and program website.”

Scholarship Funds

Scholarship criteria have a sizable impact on attracting students [18] to an institution. International students cannot afford to come to the U.S. and pay tuition without significant scholarship aid [19]. Our analysis suggests that scholarship criteria are not negotiated into all the contracts. However, given the impact these could have on recruitment, it is important to ensure that scholarship aid is a part of contract negotiations.

Four out of five contracts, however, mention the availability of scholarships for students. Three out of the five contracts require that the pathway provider fund the scholarship for international students enrolled into the program. One contract mandates the creation of a scholarship fund with a certain percentage of the net operating tuition revenue.

Housing

Negotiation of a good package inclusive of services like pick up, drop off, housing [20], scholarship funds, and classroom buildings is highly beneficial. One representative of a pathway provider notes, “Some of the new and upcoming pathway providers are willing to not just refurbish the residential buildings but also [in some instances] construct new state-of-the-art buildings near the housing facilities of the directly admitted students.”

The housing arrangement is thus a significant element of pathway contracts. In some cases, the pathway provider manages the housing; in others, the institution is involved in organizing it. Variations include:

- The institution manages the housing arrangements. Two contracts put the university in charge of housing management for students.

- One contract details the presence of a high-quality residential facility for pathway students, and calls upon the university to ensure, in the case of the second contract, that new and refurbished buildings are available for the students.

- The second stipulates that the university facilitate the “provision of on-campus housing for students enrolled in the program,” the charges for which will be set on the “same basis and terms and conditions as direct entry students enrolled in the university’s equivalent degree programs.”

- The pathway provider manages the housing arrangements. Two contracts delegate the responsibility to the pathway provider for “determining the need and for coordinating the housing for students,” meaning that the pathway partner as an administrator provides an estimate of housing needs to the partnering institution. A third touches upon the university paying the pathway provider for the “usual customary room and board fees for students enrolled in the academic pathway and English-language programs.”

Conclusion

Universities should analyze the business model proposed to understand how the academic program aligns with student and market needs. The president of one pathway provider cautions, “The market is shifting. The overreliance on revenue share is solely via the tuition revenue of ESL/academic pathway will become a problem with current models. If there is a shift occurring, it is in the direction of ‘revenue share/commission’ on all types of enrollments, be they ESL, pathway, undergraduate, certificate, or graduate.”

He urges universities to keep in mind that pathway providers might be morphing more into full-blown recruiting companies. Moreover, the academic model surrounding tuition revenue is showing signs of weakness, such as the admission of students with lower GPAs to increase enrollments.

One pathway specialist anticipates that the “next admissions cycle will see very aggressive tactics used by the third-party providers and might be the most competitive recruitment cycle to date.” She fears that “commissions and incentives will be high, and that will lead agents to steer students to the highest payer, rather than the best university to serve their needs.”

In times to come, the “key will be to keep the student experience fundamental to the program,” as one expert said. And the key to that, of course, is negotiating a good contract that balances the need for a robust pipeline of students with robust governance mechanisms to ensure a good experience for those who enroll.

1. [22] The interviewed experts included the institution administrators and pathway providers. All interviewees and contracts are anonymized in this article.

2. [23] Ancillary courses means non-degree credit courses included in the contract.

3. [24] In the S-U system, S means satisfactory and U means unsatisfactory.

4. [25] One out of the five contracts did not have this information available.

5. [26] An agreement of this nature establishes an enterprise owned collectively and managed for joint benefit.

6. [27] We will ignore legal and tax motivations, which can become complicated

7. [28] Certificate of Eligibility for Nonimmigrant Student Status.

8. [29] The Form I-20, “Certificate of Eligibility for Nonimmigrant (F-1) Student Status- For Academic and Language Students

Additional Resources

NAFSA research on landscape of third-party pathway partnerships in the U.S. [30]